This May saw the launch of the Truth About Fur Podcast, a collaborative effort of the Fur Institute of Canada…

Read More

Simon Ward, editor, Truth About Fur

Simon Ward is a veteran environmental journalist and communicator specialising in the sustainable use of renewable natural resources, and in particular wildlife. From 1998 to 2011, he was communications director for Fur Commission USA. For an autobiographical account of Simon’s development into a conservationist, see From animal activist to adult: a personal journey. Contact Simon at [email protected]

As Society’s Grasp of Sustainability Improves, Is Fur Making a Comeback?

by Simon Ward, editor, Truth About FurAfter decades of shrinking markets amid incessant attacks from animal rights groups, could real fur actually be on the verge…

Read More

After decades of shrinking markets amid incessant attacks from animal rights groups, could real fur actually be on the verge of a comeback? And will it hinge on society's better understanding of sustainability?

Before you dismiss this is as just another puff piece from the fur trade, the mainstream media are asking the same question. Why is fur – real and pretend – everywhere again? asked Vogue this March. Can fur make a comeback? asked the Washington Post in April.

These are both prestigious titles not known for making stuff up, but there are plenty of other articles out there telling a similar story.

So if it's really true, why is it happening now? And should we really be surprised?

Understanding Sustainability

The last two decades have been tough for the fur trade, above all because of effective campaigns by animal rights groups to win over the media and vote-hungry politicians. It's impossible to count the number of media reports and pieces of legislation (particularly in the US) that have relied on half-truths and lies spoon-fed by these groups.

Two anti-fur campaigns have been particularly effective at hogging the media spotlight, in large part because they are highly repeatable. One involves pressuring well-known designer brands and retailers into dropping fur. The other seeks legal bans on fur production and retail at the town, city or state level. When one target has either capitulated or been bled dry of headlines, campaigners just move on to the next.

But while all this has been going on, the zeitgeist of society has changed dramatically. Thanks to the Internet, information is more available than ever before. And the conversation has changed too, and become more inclusive.

Above all, our focus now is on climate change. Scientists have been predicting trouble for years, but until recently they spent most of their time talking to one another, and most of us had little say. But now we're all involved, and many more of us can talk intelligently on topics as diverse as single-use plastics, watershed pollution, habitat loss, greenhouse gases, ozone holes and carbon footprints. Our grasp of these concepts has come on by leaps and bounds in a very short space of time.

As a result, some of the arguments the fur trade has been making for decades are now resonating with a much broader audience, among them the strongest argument in fur's favour: sustainability.

Just to recap the facts, in case you don't already know: Fur is a renewable natural resource, which means it is, by definition, sustainable. In contrast, petroleum-based synthetics like polyester, that now dominate the fashion industry, are non-renewable and therefore unsustainable. And contrary to what animal rights groups may want us to believe, fur is biodegradable, petroleum-based synthetics are not, and the environmental footprint of fur production is insignificant in comparison to that of synthetics.

SEE ALSO: Fur, a renewable resource. Fur Is Green.

Less Gullible

Because most people now get the facts, we are also far less gullible than we once were. How many of the following half-truths and lies did you once believe but now reject?

• Fake fur is better for the planet than real fur, because it does not involve killing animals. This is demonstrably false on several grounds. Both extracting petroleum and producing fake fur are polluting processes which kill millions of animals indirectly. Furthermore, fake fur sheds harmful microplastics into the food chain when washed, and at the end of its life, it's either burned or sits in landfills, causing further pollution.

• For the same reason, "vegan fashion" is good for the planet. Most vegan fashion is made of plastic, while much of the rest uses cotton, with all the harm to the environment that cotton production entails. Do you remember "pleather"? It didn't take a genius to figure out it was made of polyurethane, so marketers rebranded it as "vegan leather". But it's the same thing.

SEE AlSO: What is "vegan fashion" and how true is the hype? Truth About Fur.

• Fur is a special case because it's especially "cruel" and "unnecessary". All animal-users have known for years that this claim is false. Fur is just a soft target, and the ultimate goal of the animal rights movement is to end all animal use. In 2022, longtime advocate of sustainable use Canada Goose yielded to pressure to drop fur, hoping animal rights groups would leave it alone. Instead, protesters just took aim at its use of down stuffing instead.

SEE ALSO: Canada Goose retreats from fur. We should all worry, not just trappers. Truth About Fur.

• Inhumane treatment of animals is unsustainable. Despite the fact that animal welfare and sustainability are fundamentally different issues, animal rights groups have enjoyed great success persuading fashion brands and retailers to drop fur by convincing them they are part of the same package. Companies like Gucci and Canada Goose have even incorporated animal welfare into their sustainability policies.

SEE ALSO: Sustainability: Why is Gucci so confused? Truth About Fur.

How many consumers now see through such nonsensical arguments is impossible to say, but surely the number is growing, and product endorsements from animal rights groups are fast losing their value.

Mob Wife Look

So against this backdrop, why do some media pundits think fur's comeback may be happening right now?

Almost every story about fur's comeback in the last few months mentions a fashion trend called the "Mob Wife aesthetic". Born on TikTok, the Mob Wife look asks ladies to dress how they think the wives of Sonny Corleone, John Gotti or Tony Soprano dress. And the look is not just for clubbing. If you're visiting the grocery store, throw on your leopard-print jumpsuit, high heels, giant shades and bling jewellery, and top it all off with a fur stole.

SEE ALSO: TikTok’s ‘mob wives’ trend is fueling a resurgence of fur. CNN Style, Feb. 1, 2024.

But where did the Mob Wife look itself come from? Fashionistas theorise that there's a rebellion against the "clean girl" and "quiet luxury" looks, but at a deeper level, there may also be a connection with our improved understanding of sustainability.

Here's the logic. As we question "fast fashion", reliant as it is on petroleum-based synthetics, we are turning to "slow fashion", with investment pieces made of more durable, natural materials. And as part of this trend, we're also seeing a surge in recycling, including buying used clothing at thrift stores.

Enter vintage furs. They're both slow fashion and recycled – and an integral part of the Mob Wife look.

On balance, growth of the vintage fur market must be beneficial to the fur market as a whole. A nuanced ethical debate is now being played out by people who – for now, at least – say they reject new fur because it involves taking animal life, but embrace vintage fur because the animals are dead anyway. Indeed, putting their fur to good use, they say, is actually more ethical than throwing it away.

So now there's a mix of people out there, wearing new, vintage and fake fur, all acknowledging its beauty and functionality, while having a spirited debate about which is more sustainable. This is far more positive than the predictable pro- and anti- arguments we've been hearing for decades (and that the media are probably bored with).

Meanwhile, realists point to the fact that supplies of vintage furs are limited, and that as supplies dwindle, some of its fans at least will switch to buying new.

What the future holds for fur is hard to predict, but we are now in an age of greater awareness about sustainability, and are counting on consumers to make wise choices. An obvious loser will be petroleum-based synthetic garments, while winners will come from a range of renewable natural resources. That should include fur.

On July 28-29, the Fur Institute of Canada descended on Whitehorse, Yukon, for its first in-person Annual General Meeting in…

Read More

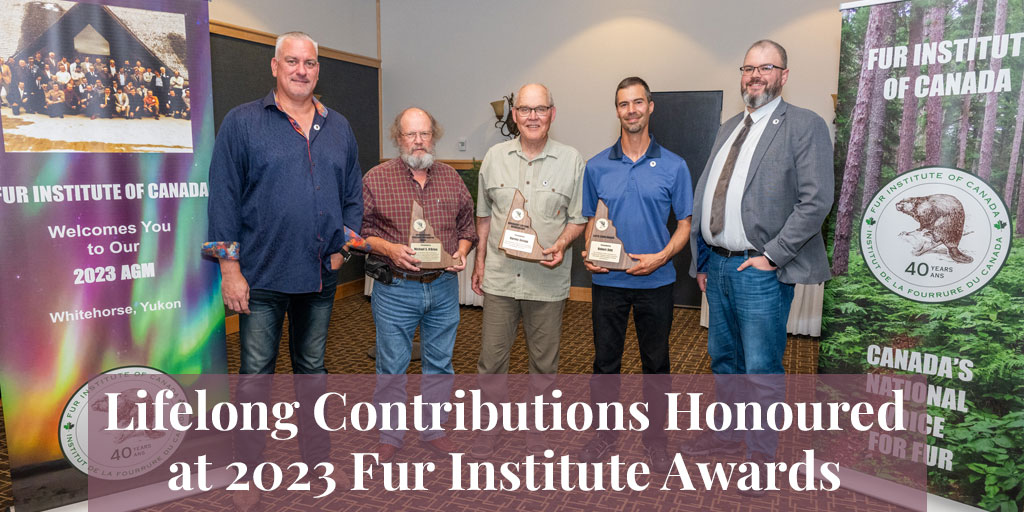

On July 28-29, the Fur Institute of Canada descended on Whitehorse, Yukon, for its first in-person Annual General Meeting in three years, and also to mark its 40th anniversary. As part of the celebrations it revived its Awards Program, honouring lifelong contributions to the fur trade.

This year, three awards were presented: the Lloyd Cook Award, the Honorary Lifetime Membership Award, and the North American Furbearer Conservation Award.

Lloyd Cook Award

The Lloyd Cook Award was first presented by the FIC in 1993 in recognition of its namesake's commitment to excellence in trapping, trapper education and public understanding of wildlife management. Among the posts held by Lloyd in his lifetime were the presidency of the Canadian Trappers Federation and of the Ontario Trappers Association, forerunner of today's Ontario Fur Managers Federation.

This year's Lloyd Cook Award went to Robert Stitt, a valued member of the FIC for almost two decades. Robert was unable to attend the presentation, so the award was accepted on his behalf by Ryan Sealy, a conservation officer with the Government of Yukon.

Robert grew up in Ontario where he spent decades trapping and guiding hunters, before moving to Yukon in 2008. One of the first things he did on arriving was to join the Yukon Trappers Association (YTA), and, despite his enormous experience, signing up for the territory's Basic Trapper Education course. To this day, he is a director of the YTA, as well as being a past president.

For the past 15 years, Robert has run a trapline in a remote part of southeast Yukon, harvesting marten, beaver, wolf and wolverine. In most years, he offers upgrading workshops, particularly for marten and beaver pelt-handling and management, and also provides a mobile fur depot service in several communities.

In 2011, Robert became a guest presenter for the Yukon Government's trapper education program, and in 2020 became an instructor. Students regularly comment on his close connection to the bush, his willingness to help new trappers, and his strong advocacy for humane trapping and good fur-handling.

Indeed, Robert's fur-handling skills are renowned, and the reason he has won many competitions. When teaching, he highly recommends his students read the Fur Harvesters Auction manual Pelt Handling for Profit.

Robert's other claims to fame are diverse. He is known as a presenter and writer, regaling audiences with inspirational tales of overcoming extreme challenges in the wilderness. He often writes letters to the editor on wildlife management issues, has published several stories about his life on the trapline, and is a regular contributor to Canadian Trapper magazine. And he is also a renowned moose-hunting guide, and a valued reporter on birds and other wildlife on his trapline.

Honorary Lifetime Membership Award

The FIC's Honorary Lifetime Membership Award celebrates people with long and distinguished track records of service to the fur trade, this year going to a man who has been involved with the institute from its inception, Yukon resident Harvey Jessup.

Harvey started his career in fish and wildlife management as a conservation officer, moving from enforcement to management in 1977 as a furbearer technician assisting with research on furbearer species such as marten, beaver, lynx, wolverine and wolves. This research led to the development of trapline management strategies for these key species. With the assistance of many Yukon trappers, the Yukon Trappers Association, the Manitoba Trappers Association, and the Canadian Trappers Federation, he developed a trapper education manual and training program for Yukon that is still in use today. He sat on the Western Canadian Fur Managers Committee which would later be incorporated into the Canadian Fur Managers Committee.

In 1982, Harvey became the fur harvest manager responsible for traplines, monitoring fur harvest and delivering trapper training. He continued as a member of the Canadian Fur Managers Committee. He attended the founding meeting of the FIC, was appointed to its first Board, and went on to serve for over 20 years. He held positions on the Executive and chaired the Trap Research and Development Committee for six years. He also participated on ISO191 through to the development of the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards.

His responsibilities with Environment Yukon expanded to include all wildlife harvest, managing licensed hunting, determining outfitter quotas and tracking harvest. He eventually became Director of the Fish and Wildlife Branch, before retiring in 2009.

In 2010, he was appointed to the Yukon Fish and Wildlife Management Board (YFWMB), a government advisory body established under Yukon First Nation Final Agreements, and served as chair for two years. Interestingly, the Director of Fish and Wildlife is identified in the Land Claim as the YFWMB's technical support, so Harvey has sat on both sides of the table so to speak!

In 2015 he was appointed to the Yukon Salmon Sub-Committee, a Land Claims advisory board on all matters pertaining to salmon in Yukon, again serving as chair for two years.

Throughout the latter part of his career and while sitting on the YFWMB, Harvey worked closely with Renewable Resources Councils, local government fish and wildlife advisory committees that have direct responsibilities for all matters pertaining to trapping.

North American Furbearer Conservation Award

The North American Furbearer Conservation Award aims to promote awareness and recognition of individuals and organisations that have made significant efforts in the field of sustainable furbearer management. This year's award went to Mike O’Brien from Nova Scotia.

On graduating from Acadia University with a master's degree in wildlife biology, Mike worked as a wildlife manager for the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables of the Government of Nova Scotia. He then became a consultant for many different wildlife management sectors, including the wild fur trade.

Mike has been an FIC Board member since 1998, serving first on the Trap Research and Development Committee, and currently as chair of the Communications Committee. He is also a member of the Executive Committee.

In his work for the FIC, Mike's forte is representing the institute at conferences involving diverse stakeholders and often contentious negotiations. These include the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. He also works closely with other key stakeholders such as Environment and Climate Change Canada and the International Organization for Standardization.

This year marks the passing of four decades since the Fur Institute of Canada was founded in 1983, with the…

Read More

This year marks the passing of four decades since the Fur Institute of Canada was founded in 1983, with the primary function of overseeing the testing and certification of humane traps. To mark the occasion, it has launched a new logo, but is the change purely cosmetic or is there more here than meets the eye? To find out, Truth About Fur interviewed Executive Director Doug Chiasson.

Truth About Fur: The FIC's original logo showed a beaver, a Canadian icon. Then it changed to another national icon, the maple leaf. Now you've combined the two, but with the beaver taking pride of place. What's the thinking here?

Doug Chiasson: When an organization celebrates a significant milestone, as the FIC is doing this year with our 40th anniversary, it's time for self-reflection. So we can see that while our most recent logo, of a maple leaf, did a great job of communicating “Canada”, it didn't communicate “fur” at all.

By putting a beaver front and centre, we remind people that fur and furbearing animals are our focus. And as a nod to the past, the maple leaf also appears in the roundel.

SEE ALSO: Doug Chiasson: What does the Fur Institute's new ED bring to the table? Truth About Fur, June 2022.

Why a Beaver?

TAF: Anyone with knowledge of Canada's history will understand the relevance of the beaver, but can you explain for non-historians?

DC: We often say that the history of the fur trade is the history of Canada. The pursuit of fur, particularly beaver pelts, was a defining feature of early European presence in North America and of relations with Indigenous nations. It played a role in establishing the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company, whose forts and factories are the sites of present-day communities across Northern and Western Canada.

That influence was reflected by the beaver's inclusion on the nickel coin since 1937, and its designation as Canada’s national animal in 1975.

Canada is fortunate to have a great diversity of fur resources, but when we think of fur and Canada, we think first of the beaver.

Absorbing Fur Council of Canada

TAF: The Fur Council of Canada has been around since 1964, representing the interests of the downstream side of the fur business (retailers, manufacturers, etc.). Now the FIC is in the process of absorbing the FCC. Why is this happening, and why now?

DC: It's no secret that the fur industry, not only in Canada but around the world, has faced significant adversity in recent years. The war in Ukraine, Covid-19, climate change, and other factors have hurt the entire fur value chain. So the FCC found itself in a position where it could no longer deliver on its mandate as a stand-alone organization.

TAF: So with the FIC now representing the upstream and the downstream sides of the fur trade, how will the entire trade benefit?

DC: In the past, having two national organizations representing the fur trade could cause confusion, but those days are over. Having just one organization represent Canada across the whole spectrum of the fur trade will put us all in a stronger position when it comes to advocating for fur. Whether we're talking to government, the media or consumers, there should no longer be any doubt that Canada's fur trade speaks with one voice.

Broadening Membership

TAF: From its founding, the FIC's primary role has been the testing and certification of humane traps, so it's understandable that your membership includes a lot of trapping associations. Will the FIC now be looking to broaden its membership base?

DC: As you say, the trap testing and certification program has always been a major motivator for trapping associations to support the FIC. That will not change with these recent developments. Other sectors of the trade have always been welcome to become members, but usually they would choose to join either the FIC or the FCC. Now there is no need for them to make that choice.

We're also no strangers to representing trade sectors other than trappers, most notably the sealing sector. Through projects like Canadian Seal Products and Proudly Indigenous Crafts & Designs, we have shown that we are capable of far more than just trap-testing.

Greater involvement from processors, designers, brokers, manufacturers and retailers will allow us to draw on everyone's experiences and expertise, and help us to present the complete picture of fur in Canada to decision-makers and the public.

TAF: Growing the FIC's representation of downstream players is an exciting prospect, but are you also looking to bring more Indigenous organizations into the fold?

DC: We want the FIC to represent as much as possible of Canada’s fur landscape, and to that end, the Board have asked me to look for new members wherever we can find them. I am also working to develop a new Strategic Plan for the Institute, and want to bring a broad array of viewpoints into building that plan. That obviously includes Indigenous organizations, and that’s an area I am particularly focussed on.

Indigenous nations and governments are increasingly playing leadership roles in land use and wildlife management decisions across the country. In much the same way that we work with our partners in provincial and territorial governments, we want to work closely with Indigenous decision-makers and managers too.

The FIC already has a strong history of partnering with Indigenous groups on a wide range of issues, but now we hope to take it to the next level, and having them as members will certainly facilitate that.

To become an FIC member, download the application form here.

Before the Internet came along and transformed our lives, trying to get our opinions heard in the media was hard…

Read More

Before the Internet came along and transformed our lives, trying to get our opinions heard in the media was hard at best, and almost impossible if the newspaper, TV or radio station had national reach. As a result, most people didn't even try, including people of the fur trade. But times are changing, and certainly where local media are concerned – so much, in fact, that if you have a lifelong habit of not bothering, now would be a good time to kick it.

Realistically speaking, it's still hard to express opinions in media with very wide reach, even just a major city, unless you are invited to contribute. And for that to happen, you usually need to be a recognised authority in your field, or your views have already been published elsewhere. For Joe Shmoe, seeing just a humble letter-to-the-editor in print is still cause for astonishment and celebration.

On the local news front, though, the chances of the small guy being heard are improving all the time.

Thanks to the Internet, local media outlets have mushroomed, unfettered by constraints like the costs of newsprint, air time, or even maintaining an office. As long as you're online, you can launch a social media site, and for a few hundred bucks you can have a website or podcast. And you can then "monetize" your site to cover costs by accepting advertising.

There's a downside, of course. For example, fake news is everywhere now, and many so-called "news" sites are rubbish, existing only to generate income from clicks.

But we're all (hopefully) becoming more selective in our browsing, and quality sites have a tendency to rise to the top. Among these are local news outlets now able to realise their dreams without breaking the bank.

Perfect Example

A perfect example is VTDigger, serving the US state of Vermont since 2009. (The total population of Vermont is only about 650,000, so it's pretty local.)

In its own words, "VTDigger began as a scrappy, volunteer effort focused on investigative journalism. Since then, it has grown into Vermont’s most essential news organization, powered by more than two-dozen journalists and boasting the state’s largest newsroom."

Importantly, it doesn't just produce original reports. It also goes out of its way to encourage readers to submit opinion pieces on matters of local interest. And one of these happens to be wildlife management, with an emphasis on regulations for trapping furbearers.

So if Vermonters weren't informed before, they must now be one of the most informed communities in North America on this subject. A simple search of VTDigger's website for the term "trapping" brings up literally hundreds of opinion pieces submitted by readers, so many in fact that we'll list only a few of the more recent ones here:

Kevin Lawrence: Anti-hunters contribute nothing to Vermont’s wild places. June 11, 2023.

Jim Taylor: Four tribes of Abenaki do not support the anti-trapping movement.' June 4, 2023.

Will Staats: Vermont’s trapping culture is being threatened. May 7, 2023.

Brehan Furfey: Wildlife conservation depends on regulated trapping. April 20, 2023

Ray Gonda: The value of trapping vs. the anti-establishment animal rights persons. April 18, 2023.

Mike Covey: If you don’t like fishing, hunting or trapping, then don’t partake. February 8, 2023.

Bruce Baroffio: Trapping has a process for best management practices. February 7, 2023.

Paul Noel: No one more than a trapper wants to avoid catching a domestic dog. January 19, 2023.

Wider Audience

As icing on the cake, many of these opinion pieces find an audience beyond readers of VTDigger – sometimes far beyond.

That others are interested is unsurprising, since the debate about trapping regulations is playing out across North America. But how does word spread?

SEE ALSO: When pet dogs are accidentally trapped, why are media reports so unbalanced? Truth About Fur.

Again, it's all down to the power of the Internet.

I first learned about VTDigger when its opinion pieces started showing up in my Google Alerts feed. This is a free web content monitoring service, but there are many others, and millions of people are using them. Or there are many other ways you might stumble on these pieces, the most common being "shares" on social media sites.

But this not an article promoting one local media site that happens to have a lot of quality trapping content. VTDigger is just an example which shows how local media are entering a golden age, and, if they're smart, they are positively encouraging their readers to engage.

SEE ALSO: "Fur Fights Back!" It's time for a strong industry communications campaign. Truth About Fur.

So if your local news site is already engaging with its audience, that's great. Get involved, and put pen to paper! If not, encourage them to change their ways, and by all means point to VTDigger as a shining example of what can be achieved.

Also tell your trappers councils, associations, and national organisations like the Fur Institute of Canada, Fur Takers of America and the National Trappers Association, when you see opportunities for us to push back on anti-trapping and anti-fur propaganda in local news.

And last but by no means least, feel free to submit your opinion to Truth About Fur for publication as a blog post.

Like any advocacy group, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) thrives on media attention, and when a campaign…

Read More

Like any advocacy group, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) thrives on media attention, and when a campaign generates that attention year after year, you keep it going. That's how it has been with PETA UK's 20-year campaign to have bearskins removed from the heads of the King's Foot Guards.

As long as PETA fails to achieve its goal – something it's "successfully" failed to do since 2002 – this gift just keeps on giving. Indeed, so successful has PETA been at failing, that cynics now wonder whether it wants to win at all, since winning would kill the goose that lays the golden eggs.

Bearskin caps are actually worn by the military and marching bands of no fewer than 10 countries, including Canada. But above all they are associated with British pomp and circumstance, and are a must-see for any tourist visiting London. It's hard to imagine the Changing of the Guard without them.

For the last two decades though, PETA has been badgering the UK's Ministry of Defence (MOD) to drop bearskins and go fake instead. True, the synthetic replacements would be made from polluting petroleum, but PETA calls them a "vegan upgrade", so they must be good for the planet, right?

To no one's surprise, the MOD has resisted – in deeds if not always in words. And all the while, PETA has milked the to-and-fro for its endless supply of free publicity.

Life of Its Own

When PETA started this campaign, it probably never dreamed it would take on a life of its own.

Its humble beginnings came straight out of the standard PETA playbook. Pick a target (the Guards), trot out the usual stories about how terribly animals (black bears) suffer, then see if the media would take the bait.

Not interested, said the MOD. The Guards took "great pride" in wearing an "iconic image of Britain", and wearing plastic just wouldn't be the same.

But unlike the MOD, the media were very interested, because the story provided a perfect mix of what readers craved. The visuals came easily: a spectacular photo (or five, for the tabloids) of Guards on parade (just as we have done), with the Queen or other prominent royals for good measure. Then the text need only mention the royal family and suffering animals to provoke a range of strong emotions, and a PETA spokesperson would happily provide the mandatory quote while blowing their own horn. Perfect for selling papers, and perfect for PETA.

Indeed, the free publicity came so easily that PETA just had to keep it going, but how? Then it had a brainwave: offer the MOD a fake alternative specially developed to meet its requirements, and hope the MOD played along. Crucially (some say naively), the MOD did just that, agreeing to test whatever PETA came up with. PETA's foot was firmly in the door.

And so began PETA's partnership with fake fur maker Ecopel, knowing that if they could keep supplying prototypes, headlines would be guaranteed at least until the MOD capitulated, and that could take years.

Since 2015, the MOD has conducted tests on four iterations of fake bearskin, and each time determined that they don't meet requirements. PETA, meanwhile, says its latest offering meets, or even exceeds, those requirements, and is now threatening legal action, accusing the MOD of failing to fulfill its "promise" to carry out a proper evaluation.

All the while, fresh publicity is generated for PETA every time photos of glamorous Guards and royals adorn the media. And this will continue for as long as PETA keeps feeding the media fresh hooks to hang their stories on. Next, presumably, will be the lawsuit itself, but whether it is thrown out or not, PETA will be there, lapping up the attention.

Trans-Atlantic Cooperation

Of course, the MOD realises now that it's painted itself into a corner, especially when it has to answer questions in Parliament, as happened this July. So all the fur trade can do is ensure the MOD has the best information available.

Particularly concerned is the Fur Institute of Canada (FIC), since the bear pelts used in the MOD's bearskins are sourced exclusively from Canada.

"The good news is that the MOD are completely on-side," says FIC executive director Doug Chiasson. "They understand that Canada's black bear harvest is strictly regulated and informed by both the best available science and Indigenous knowledge. They know that black bears are abundant here, and that they must be managed to ensure the health of the overall population while limiting human-wildlife conflict. And particularly important in the battle against PETA, they know that we don't kill bears to order. The same number of bears will be hunted whether the MOD buys them or not."

SEE ALSO: Doug Chiasson: What does the Fur Institute's New ED Bring to the Table? Truth About Fur.

The FIC and MOD have also discussed all the benefits of natural fur compared to the petroleum-based variety. It's a renewable natural resource, fur garments last for decades, and they biodegrade at the end of their long lives.

"They get all this," says Chiasson. "They get that synthetics are polluting, that microfibres are piling up in our oceans and even in the food chain, and that they don't biodegrade. They get the importance of wildlife management, and of adherence to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species."

But that doesn't mean it's time to relax, he cautions.

"Just because the MOD has all the arguments on its side, doesn't mean we've won. Under the current Conservative government, bearskins are probably safe, but with the UK's departure from the EU, pressure is mounting to ban all fur imports. If Labour wins the next general election [to be held no later than January 2025], the future of bearskins will be up in the air. So we must remain vigilant, and continue to ensure that the MOD and other parts of the UK government have the most accurate information at their fingertips to fight the disinformation from PETA."

Meanwhile PETA UK just keeps counting all the golden eggs this goose has laid, and wondering how long it will live. Obviously the MOD doesn't want PETA to win, but maybe PETA is in no hurry to win either!

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Animal activists want to drive all animal users out of business, so it pays for the fur trade to keep…

Read More

Animal activists want to drive all animal users out of business, so it pays for the fur trade to keep abreast of their latest tactics. One now being pushed hard is "vegan fashion", but what exactly is it? And how true is the hype? Does it really save animal lives, as proponents claim? And is it really more sustainable than alternatives?

First up, what qualifies as vegan fashion?

There is no strict definition, but the general idea is that no animals can be killed or harmed in any stage of its production. So it's much like a vegan diet, except that you keep it in your closet.

But there is one important difference. Vegans only eat plants, but if you think they only wear plants, think again. Vegan fashion also contains lots of synthetics made from oil.

The most popular plant fibre with vegan fashionistas (and everyone else, for that matter) is cotton, but there are a lot of other choices. Some are familiar, like linen, hemp, cork and rubber, while others are obscure, like ramie, banana leaves, mushrooms and even coffee grounds!

Then there are semi-synthetics derived from plants, like bamboo rayon, viscose from wood pulp, and modal (made from the pulp of beech trees).

And then there are all the petrochemical synthetics vegans can wear with a (supposedly) clear conscience, like polyester, spandex, nylon, PVC and acrylic. Vegans say they prefer if their synthetics are recycled, not virgin (new), but since most recycled synthetics contain some virgin product for added strength, it's hard to know if they're getting what they want.

As for materials that are off-limits, some are obvious, like leather, fur, wool and silk. But others require vigilance if they are to be avoided.

For example, the glue used in shoes and handbags normally contains collagen derived from animals. So vegans must seek out synthetic alternatives, even if there are health risks associated with making and using them.

They must also avoid screenprinting inks containing gelatin from cows and pigs. A popular synthetic alternative is plastisol, but again, vegans must look past the health risks of the phthalates usually found in plastisols.

And a minefield for vegans is buying cosmetics and personal hygiene products. Anything with honey, lanolin or keratin is out, as are soaps, shampoos, shaving cream and lotions containing stearic acid from animal fat. If your skin moisturiser contains glycerol, beware that the most common source is tallow, a rendered form of beef or mutton fat.

So Does Vegan Fashion Really Save Animals?

The main claim made for vegan fashion is that no animals are killed or harmed in its production. At first glance this sounds logical, but the claim does not stand up to scrutiny. It would be accurate to say that no animals are bred and killed to produce vegan fashion, but plenty of animals still die.

But before we start pointing fingers at who kills most animals, we need to recognise that there are different ways of counting animal lives, depending on our biasses.

In theory, we should give equal weight to all lifeforms, such that swatting a fly is equal to slaughtering a cow. In practice, though, we never do this. We prioritise, valuing some species over others.

Most of us are class-biassed (mammals trump reptiles, for example, and insects always come last). We prefer benign herbivores to carnivores that might eat us. Beautiful animals come before ugly ones. Or if you're a conservationist, an endangered native species always beats a plentiful invasive one.'

And all these biasses give rise to paradoxes that can be hard to reconcile, like self-proclaimed "animal lovers" who feed their pet dogs the meat of other animals, bathe them to kill ticks and fleas, deworm them, and give them vaccines tested on other dogs in labs.

Vegans, of course, have their biasses too, so when they say vegan fashion saves animal lives, which animals do they actually mean? All animals? No. Above all, they mean barnyard animals that are purposely bred to provide food and clothing.

If their calculations were to include all animals, would switching to vegan fashion really save lives? It's highly unlikely, and in fact the death toll would probably rise.

Killer Cotton

Now let's take a closer look at what are probably the two most common materials in vegan fashion, cotton and polyester, and ask how animal- and environment-friendly they really are.

Everybody loves wearing cotton, but we also know that growing it – especially by traditional methods – is punishing on the environment.

The trouble starts the moment natural habitat is destroyed and replaced by a monocultural plantation. Then the crop is notoriously thirsty, often requiring far more water than can be supplied by rain alone. And then there's the heavy use of pesticides. All of these factors exact a toll on animal life, as well as damaging the environment in other ways.

Much of the killing is intentional, as farmers wage war on the myriad insects that cotton attracts. Bollworms, boll weevils, mirids, aphids, stink bugs, thrips, spider mites – the list is long.

And once the insecticides have fulfilled their purpose, they don't stop killing, or even stay within the confines of the plantation. They drift on the wind, and wash into waterways. Birds, lizards and amphibians die when they eat insects or seeds that have been sprayed, or mistake insecticide granules for food. Fish die when insecticides enter rivers. Pollinators like bees die too, often resulting in lower crop yields.

Genetic modification of cotton is helping reduce the need for insecticides, but there's still a long way to go. Meanwhile, so-called organic cotton, which uses far less in the way of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, still only accounts for 1-2% of global cotton production.

Other unintentional deaths occur when water supplies are mismanaged, harming or even destroying surrounding habitat. To appreciate just how badly things can go wrong, look at Central Asia's Aral Sea – or what's left of it. Once the world's fourth-largest lake, tributaries were diverted to irrigate crops, mainly cotton, and most of the sea just vanished. Billions of animals surely died, and populations may never recover, including 20 local species of fish now thought to be extinct.

In short, if we all ditched leather, wool and fur tomorrow, and increased cotton production to fill the shortfall in clothing materials, the total number of animal lives lost would certainly rise.

Plastics Are No Better

So how about the other staple material of vegan fashion, polyester? Its credentials as a clothing material are impressive. It's cheap, durable, wrinkle-resistant, stretchy, lightweight, quick-drying, it breathes and it wicks moisture. No wonder it accounts for at least half the world's clothing, and dominates fast fashion and sportswear.

But like cotton, it's also terrible for the planet. It's made from non-renewable oil which must be extracted from the ground. The manufacturing process leaves a big carbon footprint – up to 40% of the fashion industry’s total CO2 emissions. When washed, polyester garments release microfibres that pollute the oceans and are now turning up in the food chain, even in drinking water. Polyester is also part of the bigger problem of plastic pollution in general. A widely cited estimate is that plastic pollution kills 100,000 marine mammals and turtles, and a million seabirds, every year. And of course, these plastics don't biodegrade.

In their defense, vegan fashionistas say that a lot of the polyester they wear is recycled, which means it's actually good for the environment, "sustainable" even. But this is essentially an exercise in denial.

Recycling polyester is indeed less harmful to the environment than creating virgin polyester. It consumes a lot less energy and water, and CO2 emissions are far lower. But that doesn't make it good – just less bad.

Furthermore, recycling polyester cannot possibly be sustainable since it is inherently dependent on a nonrenewable resource. All it does is extend the life of polyester already in circulation. Plus, limitations in current recycling technology mean that recycling polyester actually perpetuates demand for virgin polyester. Each time polyester is recycled, it loses strength, and this problem is rectified by mixing in virgin material. And when polyester is blended with other fibres (typically cotton), recycling is all but impossible. Last but by no means least, just like virgin polyester, recycled polyester still sheds microfibres and does not biodegrade.

SEE ALSO: The Great Fur Burial, Part 1: Burial. Truth About Fur.

Accusations of Greenwashing

Just to confuse consumers even more, companies producing and using petrochemical-based synthetics now routinely face accusations of greenwashing – making false claims about the environmental friendliness of their products.

It comes as no surprise when animal activists engage in greenwashing, since they have never let the truth get in the way of a good story. So if they tell you wearing recycled soda bottles will reduce global warming, you can believe it or not.

More troubling are apparent efforts by the fast-fashion industry to improve its public image. Having faced a storm of criticism in recent years for various practices, the industry is now desperate for a makeover, which includes casting petrochemical synthetics in a better light.

But now the media, consumer protection groups, and others are asking tough questions.

Matters came to a head last June, when the New York Times ran an in-depth article entitled "How fashion giants recast plastic as good for the planet". Renaming products is just one way, the article says. For example, fake leather used to be called "pleather", a clear indicator of its plastic origins, typically polyurethane. But now it's called "vegan leather", a change the NYT calls "a marketing masterstroke meant to suggest environmental value."

In critics' crosshairs is the controversial Higg Index, launched in 2012 by the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC), a nonprofit group that includes major fashion brands and retailers, and the US Environmental Protection Agency. Intended to rate the environmental impact of various fabrics used in clothing, the Index "is on its way to becoming a de facto global standard," says the NYT.

But hold on, the article continues. The Index "strongly favors synthetic materials made from fossil fuels over natural ones such as cotton, wool and leather. Now, those ratings are coming under fire from independent experts as well as representatives from natural-fiber industries who say the Higg Index is being used to portray the increasing use of synthetics as environmentally desirable despite questions over synthetics’ environmental toll."

In particular, critics say the Index doesn't accurately reflect the full life-cycles of synthetics, including harmful emissions during production, how much ends up in landfills or incinerators, and microfibres polluting the oceans.

Shortly after, the SAC announced that it was pausing the use of consumer-facing Higgs labels globally, following a conclusion by the Norwegian Consumer Authority that the Higg Index was misleading consumers.

Bottom Line

While the debate will continue to rage about how best to clothe 8 billion humans, the simple truth is that all currently available alternatives have their downsides. They all result, directly or indirectly, in the deaths of animals, and leave environmental footprints of varying size.

But since the two major claims being made for vegan fashion are simple, let's try to answer them in simple terms:

Does vegan fashion save animal lives? If enough people were to wear vegan fashion, and especially if they were to adopt a vegan diet too, fewer barnyard animals would be bred. So in that sense, yes, vegan fashion has the potential to save the lives of domesticated species like cows, pigs and sheep. But if all animal lives are given equal weight (i.e., a snake or boll weevil is equal to a cow), this saving would be more than offset by the loss of animal life caused by converting more land to plant agriculture.

As for petrochemical synthetics like polyester, it is now universally recognised that their usage is harmful to the environment, including wildlife. So even if your polyester blouse is made from recycled soda bottles, it may slow the production of virgin polyester, but in the long term it offers nothing in the way of a solution.

Is vegan fashion more sustainable than alternative choices? There is almost no basis for this claim, as vegan fashion currently exists.

Noble efforts make the headlines regularly as innovative companies strive to develop more sustainable materials and methods of producing them. But we're not there yet. Which means that vegan fashion will continue to rely on crops like cotton, which are harmful to the environment, and petrochemical plastics like polyester, which are not only harmful but also the antithesis of sustainable.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Like most writers, those of us in public relations are prone to vanity. If we can choose between having an…

Read More

Like most writers, those of us in public relations are prone to vanity. If we can choose between having an op-ed piece in a prestigious newspaper or a column in the local supermarket rag, we choose the former, even if it means far fewer people see our work. So is our professional pride causing us to ignore the power of low-brow publications to change hearts and minds? In particular, should the fur trade be taking the UK tabloids more seriously?

The UK Is a special case for a few reasons, notably:

• Everyone speaks English. There’s no denying the impact of the English language in shaping any debate of international concern, including the fur debate. By all means publish in Russian or Portuguese, but don’t expect a global audience.

• The entire UK is a little smaller than the state of Michigan, so many print tabloids (and of course their affiliated websites) have national circulations. Indeed, two in particular, the Mirror and the Sun, are said to carry more weight in national elections than esteemed broadsheets like the Telegraph and the Guardian.

• The UK is the spiritual home of the animal rights movement. When it comes to activists making life hard for animal industries, only Californians come close.

SEE ALSO: Brexit, fur-trimmed parkas, and trendy vegans in London Town. Truth About Fur.

Check Out the Boots!

Enter the Daily Mail, the country’s most notorious tabloid since the News of the World was forced to close a decade ago. On May 23, the Mail ran a piece on two huge fans of fur, Judi Caldwell and partner Lukasz Dlubek from Northern Ireland, while commissioning Mercury Press to take lots of lovely photos. (We all like photos, but for the tabloids, they are essential, and the more provocative the better. Conveniently, Lukasz looks like a cross between Conor McGregor and a member of Ukraine’s Azov regiment. One look at his boots would send most Russian soldiers running!)

This article was not standard Mail fare, but not unprecedented either. Typically, Mail pieces on fur are negative, and for the last several years have involved recycling old photos from a Scandinavian fox farm, with regurgitated sound bites from animal rights leaders implying they have just concluded an “investigation”.

Sometimes, though, the thoroughly unprincipled Mail will change tack on an issue completely, just to keep readers on their toes. This time it chose to tell us that some people – well, these two anyway – think fur is great.

The headline (if this can be called a “headline”) literally says it all: “Couple who love the ‘classy’ feel of wearing real fur claim they have ‘higher morals’ than the vegans who send them death threats online because it’s more sustainable than fake fabrics.”

Then for good measure, the body reiterates the main points: “The pair believe that not only does wearing real fur make them look incredible, but they also say that it is more sustainable and environmentally friendly than faux alternatives and a lot of vegan products.”

Says Lukasz (of the scary boots): “Real fur lasts for so much longer when it’s cared for correctly whereas fake fur is fast fashion – what do they think happens to all the plastic that is used to make it!”

Judi drives the message home: “Nowadays, there is a lot of ‘green washing’ and a big emphasis on veganism and vegetarianism. We are trying to promote sustainable fashion by wearing fur, but people are quick to jump online and judge us.”

SEE ALSO: Fur is a sustainable natural resource. Truth About Fur.

The point about sustainability is well made, of course, and especially pertinent in the UK where the absurd notion is widely accepted that “vegan fashion” (including clothes and shoes made from plastic) is, almost by definition, more “sustainable” than anything which involves the direct killing of animals.

But as anyone familiar with the Mail knows, it is not in the business of educating people. It just wants outraged readers to go, “Whoa! That’s crazy!” – then share the piece widely and hopefully click on some ads. (If you find this interpretation too cynical, another headline used for the same article by an Indian website tells us exactly what we’re supposed to think: “Bizarre: Couple who wear real fur say they are ‘more sustainable’ than vegans; leaves netizens confused.”)

Then the Mail throws more fuel on the fire by having Judi suggest vegans are psychopaths. “The hate we receive from a lot of vegans online is appalling,” she says, “and I’ve even had messages from someone who was threatening to slit mine and my dog’s throat because we wear fur.”

Incredible Reach

Since money is the only reason the Mail publishes such stories, and almost no one reads the comments that follow, it makes no sense for the fur trade to bother responding. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to get in the game. The reach of these stories is potentially enormous, and frequently far greater than anything published by a reputable media company.

For starters, big UK tabloids like the Mail belong to larger media groups with a slew of other outlets, both in print and on the web, including every popular social media platform. The Mail comes under the umbrella of DMG Media, whose stable includes Metro.co.uk, a tabloid website that also ran a pared-down version of the Judi and Lukasz story. And though we have not confirmed this, it seems highly likely that the story also ran in the print version of Metro. This is the UK’s largest-circulation tabloid (though the fact it’s free must help).

Then there’s life beyond DMG Media. Within days of the Mail publishing its story, it popped up on News India Studio, WST Post, Unilad, Granthshala News, News Dubai, and an ominous-sounding site called Internet Cloning. And these were just the links near the top of our Google search.

Only through serious research could we know which of these recyclers are legitimate and which are simply plagiarists. But that’s the problem of DMG Media’s licensing department.

The fact is, though, that the stuff of UK tabloids is perfect fodder for today’s legions of ad-driven websites employing underpaid rewriters to push trending news stories. In short, a shoddily written story, with no redeeming qualities other than a catchy headline and provocative photos, can reach far more hearts and minds than an op-ed piece in a prestigious broadsheet ever can.

The fur trade has always tried to take the high road when it comes to public relations materials. But maybe we should be taking the low road too. Everyone else is.

***

If you have a story that you think would be good fodder for the UK tabloids, send it our way and we’ll see if we can get an editor to take the bait! It needs to promote the message that fur is sustainable, and don’t forget the pics. But other than that, anything goes!

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

BC Mink Farming Ban: Government Refuses Compensation for Devastated Families

by Simon Ward, editor, Truth About FurBritish Columbia’s Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries has yet to show any science to justify its drastic decision, last…

Read More

British Columbia’s Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries has yet to show any science to justify its drastic decision, last November, to introduce a mink farming ban in that province. The failure to provide any serious evidence that mink farming might compromise efforts to combat Covid-19, as the government – echoing animal activists – claimed, raises questions about its real motivation. Even more alarming, the government has refused any compensation for the farm families whose life work and livelihoods have been wiped out.

Rewind to July 2021. After three of BC’s nine mink farms had tested positive for Covid-19, the Ministry of Health drafted an order imposing a moratorium on any further breeding. Since the order would expire in January 2022, before the start of the next breeding season, it did not constitute an immediate threat to farms. But the possibility that the order might simply be extended made planning impossible. So the farmers objected, and the final order instead just prohibited them from increasing the current size of their herds.

Then in August, the government upped the ante dramatically, advising mink farmers that a ban was being considered. In response, the farmers collected a broad range of science demonstrating that, with proper biosecurity measures in place, mink farming could continue without endangering public health. Included were materials from the World Organisation for Animal Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, and the National Veterinary Services Laboratory in the US; and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

In direct contradiction of this international scientific consensus, on November 5 the BC government dropped the bombshell.

First the Ministry of Agriculture called the farmers to say that the Ministry of Health had reassessed the threat posed by mink farming, and the entire sector was to be “phased out”. Breeding was permanently banned, effective immediately, the last live mink had to be gone by April 2023, and the last pelts must be sold by April 2025. After that, mink farming in BC was history.

With the farmers still reeling in shock, Agriculture Minister Lana Popham, backed up by Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry, then called a press conference the same day to publicly announce their decision.

…

So Many Questions

Immediately the questions began to fly, and not just from fur farmers. Even veterinarians and virologists with expert knowledge of mink farming were perplexed. Only one farm in BC still showed signs of Covid, so why didn’t the government just continue to keep that farm in quarantine, or even cull all its mink? Why close down the entire sector?

And there were more troubling questions the BC government has still failed to answer adequately, or at all. For example:

Question: Is the ban really about protecting the public from Covid, or is it at least in part about appeasing aggressive BC animal rights groups? Popham insists her decision was based solely on public health concerns, but has yet to provide any scientific data to justify such a radical move. Meanwhile, animal activists themselves seem to contradict her claim.

For years, the British Columbia Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (BCSPCA), The Fur-Bearers, and Humane Society International (HSI) have been campaigning to end mink farming in the province on “animal welfare” and “ethical” grounds. But, when Covid started appearing on mink farms, these groups immediately began scaremongering about a “public health risk”.

These groups are also known to have had many meetings with Popham over the past year, and the minute Popham announced her ban, they began congratulating themselves for a job well done. Crowed HSI chief Kitty Block on her blog, “The move follows an intensive campaign by HSI/Canada, as well as our allies … HSI/Canada and our partners have consistently called on the British Columbia government to ban fur farming in the wake of disturbing reports of horrendous animal suffering in these facilities” [italics added].

Question: Why is BC so out of step with other governments tackling the same pandemic? Back in 2020, when the Danish government ordered the killing of 15 million mink, scientists knew much less than they do now about the risk of mink passing new Covid variants to humans. It’s since been established that the public health risks posed by mink farming are low and manageable, especially in a country like Canada where farms are few and remote from large human settlements. And even Denmark never banned mink farming — and is now compensating farmers to the tune of millions of dollars for their lost animals.

Further reducing the risk to public health are the unprecedented biosecurity measures being deployed on mink farms, plus a Covid vaccine developed specifically for mink, which began rolling out last year. Fur Commission USA reports that about 95% of that country’s mink herd have now been vaccinated, and Finland’s vaccination program is also advancing well. Vaccine access in Canada was limited in 2021, but Zoetis, the US manufacturer, has committed to having enough vaccine available this spring for all Canadian mink. Most of the doses available to Canada in 2021 were used on Nova Scotia mink farms, who purchased them through a cost-sharing agreement with the federal and provincial governments.

The BC government surely knew that vaccines were on the way, and that they promised to resolve the very public health issue it claimed to be addressing. That fact alone strongly suggests it had already decided to ban mink farming, and the imminent availability of vaccines may have forced it to advance its schedule to implement the ban.

Question: Was the timing of the ban a cynical ploy to avoid ordering a cull, and thereby having to pay farmers compensation?

It seems too convenient, from the government’s viewpoint, that the ban was announced in November, just when farmers were about to harvest their mink. The ban on future breeding put farmers under immense financial pressure to harvest their breeders as well. Within weeks, the farms were almost empty of animals, without any need for the government to order a cull – which would have automatically triggered the requirement to provide compensation.

Question: If, as the BC government claims, farmed mink really posed an unacceptable health risk in November 2021, why did it allow farmers to keep live mink until April 2023? And why were farmers allowed to sell and transport live mink to other jurisdictions?!

Question: If farmed mink pose an unacceptable health risk because they can catch Covid, what about all the other animals we now know can catch it? Pet ferrets, hamsters and cats live in homes, potentially exposing children and the elderly to the virus. Large cats and other animals in zoos have been found with Covid, as have a high percentage of North American white-tailed deer and mice. In fact, there is evidence suggesting that most mammals can transmit the virus even if they don’t show symptoms.

Question: And why just Covid? In 2004, British Columbia had an outbreak of another zoonotic disease, avian flu, worrying the government enough for it to order the culling of 19 million poultry. Then in 2009, Canada was swept by a strain of swine flu that killed at least 428 people (as of February 2017). But in neither case was the possibility ever considered of shutting these industries down. Authorities worked with farmers to mitigate the risks, as they should. BC’s mink farmers, however, got different treatment altogether. Why?

No Compensation?

The fact that the government could close down an entire farming sector, without showing any science to justify it, is cause for concern for anyone in agriculture. But BC’s mink farmers now face a more pressing problem: If the government is true to its word, farm families will not be receiving one cent in compensation, and that will spell financial ruin for many.

When Popham addressed the news conference last November, she made it sound like her ministry would do the right thing and work with farmers to help them “transition” to other activities. The issue of money was deftly skirted around, but she pledged “to help them pursue other farming, business or job opportunities that support their families.” Nice words, but to date no real assistance has been forthcoming. (Although at one meeting the government-appointed consultant did offer farmers the number for a suicide prevention hotline!)

But compensation for the farmers is not only needed, it is surely deserved. For generations in some cases, farm families strived to refine the genetics of their herds. Thanks to their efforts BC produced some of the finest farmed mink in the world, consistently ranking in the top 5% of prices at international auctions. With the stroke of a minister’s pen, all that work has been destroyed.

On November 29, Joe Williams, president of the BC Mink Producers Association (BCMPA), wrote to the ministry asking to see the science and data used to justify the ban, and requesting an urgent meeting “as decisions need to be made”. On December 10, Deputy Minister for Agriculture Tom Ethier replied. The ministry would only be dealing with “individual producers”, not “provincial, national, and international industry groups” – a strategy known as divide and rule. He also stated unequivocally, “The Ministry will not be offering compensation to mink farmers because of this ban.”

Instead of support, BC mink farmers got bureaucratic waffling. “We continue to want to work with producers to find the appropriate supports within existing government programs and support any that wish to transition to other agricultural industries,” wrote Ethier. “We will make staff available to work with mink producers to explore what is possible regarding financial support within these existing programs.”

So how have these vague promises panned out so far? “There is no deal. Nothing,” said Williams. “They are saying it’s due to Covid and they don’t have to pay. There is no compensation, they are not even paying the employees. They in fact are leaving us with massive debt.”

Massive Debt

In fact, the government’s arbitrary action will place many farmers in a deep financial hole.

BC mink farmer Terry Engebretson told the Vancouver Sun that aside from losing his job, he’ll also be stuck with millions of dollars of debt. “This isn’t a transition, it’s an eviction,” he said. “The banks are looking at us and realizing we don’t have any income.”

In 2010, Engebretson drew up a 20-year plan that included a mortgage to pay for barns, pens and a feed-preparation room. If he switched to another type of farming now, he’d have to tear down the barns while still paying the mortgage on them. And with the way many agricultural sectors in BC are supply-managed, if he switched to chickens, for example, he’d need to buy an expensive quota, assuming that it was even available.

“No bank is going to touch me,” he told the Sun. “I’d be piling debt on top of debt. I’ll be lucky if I can keep my home.”

It’s hard to see a happy ending to this story. Time will tell whether the government’s decision was really justified by the science, or whether more insidious influences were at play. What is sure is that the life work and livelihoods of farm families have been destroyed.

The Ministry of Agriculture has abruptly declared a successful and well-regulated farm sector to be illegal, without providing any scientific justification for its action. At the very least, surely it now should provide fair compensation to those affected. The BC government needs to acknowledge the suffering it is causing to citizens who have done nothing wrong, and take full responsibility for its decision. That includes loosening its purse strings immediately.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Calling Fashion Industry: Animal Welfare and Sustainability Are Like Chalk and Cheese

by Simon Ward, editor, Truth About FurAnimal welfare and sustainability are both commendable goals for any company’s strategic plan, but they’re also like chalk and cheese….

Read More

Animal welfare and sustainability are both commendable goals for any company’s strategic plan, but they’re also like chalk and cheese. They’re unrelated, which means you don’t advance one by advancing the other. Yet these days, whenever a designer, brand or retailer announces it is dropping fur supposedly for animal welfare reasons, it also claims this will make it more sustainable. This is totally illogical, and they must be called out for it.

Worse still, the deceit appears to be intentional, not just the result of lazy thinking. In a conscious and cynical bid to associate themselves with two of the hottest buzzwords in marketing today, companies are pitching the message, “We believe in animal welfare and sustainability, so we won’t be using furry animals anymore. (Just don’t ask about all the other ones.)”

So why should the fur trade cry “Foul”? Because sustainability is the strongest argument in favour of fur, and we need to defend it against misuse. Now the debate is being twisted and co-opted to make it appear that fur is the very opposite of sustainable.

First let’s look at sustainability and animal welfare separately, and then see how some sneaky companies pretend they are related.

Sustainability Is One Thing …

Just about every business today claims to be striving for greater sustainability, and with good reason. Not only is it good for the planet, it also sells! It’s something customers want to hear. So even if your business is not sustainable today, at least say you are trying, and promise some vague delivery date like 2030.

For a few lucky industries, including the fur trade, sustainability has already been achieved. Historically, it wasn’t always the case, as some wild species were over-harvested. But with the advent of fur farming and a raft of regulations covering harvest sizes and trade, the modern industry has become a model of sustainability.

Here are its main credentials:

- Furbearers, whether trapped or farmed, are a renewable natural resource.

- No endangered species are used.

- Fur farming provides extra protection for wildlife as production can be adjusted to meet changing demand. (This is true for all livestock farming.)

- Farmed furbearers consume leftovers from the production of human food.

- Trappers provide vital information and assistance to wildlife managers.

- Fur is fully biodegradable, even after processing, no matter what animal rights groups claim.

- A fur garment can last for decades, or be restyled as fashions change. It is the complete opposite of wasteful “fast fashion”.

These credentials look even stronger when you compare real fur to fake fur made from non-biodegradable, non-renewable oil.

… Animal Welfare Is Another

Animal welfare is a different issue entirely. While sustainability is concerned with quantifiable inputs such as reproduction rates and environmental impacts, animal welfare deals with the quality of life and death of the animals we use.

It’s difficult to explain in logical terms how companies bundle animal welfare and sustainability together, because the “logic” they employ is false. They first present an erroneous argument, hope we don’t notice, and then use this argument to justify their business strategy. It’s like saying, “2 + 2 obviously equals 5, we can all agree on that. So now let’s focus on that number 5.”

The false logic they want us to fall for is typically along the following lines. “Treating animals well will result in a kinder and gentler world, which we all want to live in. That world must also be sustainable. Therefore, being kinder to animals is integral to ensuring the future sustainability of our planet. And since it’s impossible to achieve an acceptable level of welfare in the fur trade, the most sustainable option is not to use fur at all.”

QED: Fur is unsustainable.

And when you’ve finished wrestling with the twisted logic, take special note that companies are using it only to justify dropping fur. Not leather. Or feathers. Or any other animal products. For these, it’s business as usual. In other words, the level of animal welfare in producing crocodile handbags or goose down is acceptable, and therefore these products are sustainable. What?

Case Studies

Now let’s look at three real-life examples of fashion companies that have dropped fur, and see the knots they tie themselves in to justify it.

Gucci: In 2017, CEO Marco Bizzarri shocked the fashion world by announcing that his company would be dropping fur. He also announced that Gucci had signed on to the Fur Free Retailer program of the Fur Free Alliance, a group that, in its own words, wants to end the fur trade by “raising the serious animal welfare issues related to fur farming and trapping.” The Alliance expresses no interest whatsoever in promoting sustainability. But still, Bizzarri described Gucci’s move as demonstrating “our absolute commitment to making sustainability an intrinsic part of our business.”

The remarkable thing was that only the fur trade challenged Bizzarri to explain how jumping in bed with an animal rights group and dropping fur would make Gucci more sustainable. The media were all over the dropping fur part, but not one journalist questioned the logic. Why was real fur unsustainable? Was fake fur more sustainable? And why was Gucci not dropping leather, exotic skins and feathers too?

So in one fell swoop, Bizzarri framed Gucci as loving both animals and the planet, and he got away with it.

Nothing has changed since either. If you want to know more about Gucci’s stance on animal welfare, the go-to document is titled – wait for it – Gucci Sustainability Principles! This 21-page document on sustainability refers to animal welfare no fewer than 40 times. And there are three whole pages devoted to the “Kering Animal Welfare Standards” (Kering being Gucci’s parent). Why these in-house, self-serving animal welfare standards belong in a document on “sustainability principles” is not explained, but clearly we are supposed to accept that animal welfare is an integral part of sustainability.

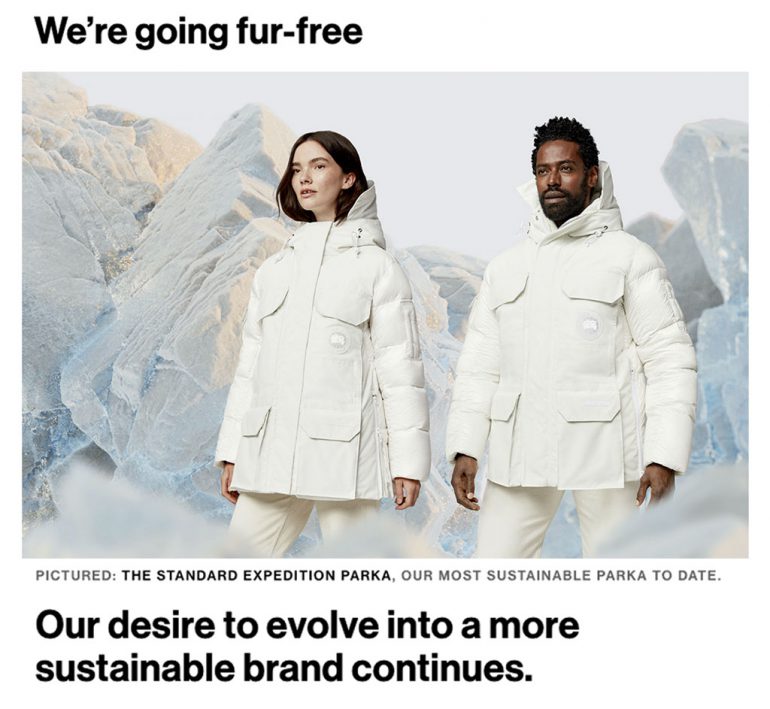

Canada Goose: Known for its iconic performance parkas with coyote trim, Canada Goose is now in a tricky spot PR-wise, largely of its own making. For decades, it was a strong advocate of fur as a sustainable natural resource – an industry leader, in fact. Indeed, a page still on its website but that will presumably disappear soon, states: “We remain committed to the functionality and sustainability of real fur.” Then last June it announced that it was dropping fur.

Observers were in no doubt that this was a response to relentless pressure from animal rights groups, but CEO and president Dani Reiss wasn’t about to admit this. Instead he dug himself a hole, saying, “This decision was driven by our commitment to sustainability …”

So the official line is that Canada Goose is dropping fur voluntarily, as part of its ongoing commitment to sustainability, and you can believe that if you want. But the really tricky part is that it can’t actually say fur is unsustainable, because it’s been saying the polar opposite for years. Which leaves us in the odd position of having to turn off our brains and accept that while fur is sustainable, “fur-free” is more sustainable.

And here’s what it looks like in practice:

This new page on the Canada Goose website sports the headline, “We’re going fur-free”, unquestionably an animal rights slogan with no connection to sustainability. But the subhead reads, “Our desire to evolve into a more sustainable brand continues.” No matter what explanation Canada Goose may have for this, it is impossible for a visitor to this webpage not to connect these two ideas. The message, intentional or not, is clear: Canada Goose is going fur-free BECAUSE it is more sustainable.

Mytheresa: And this quote says it all – no further explanation required. This August 26, the Munich-based luxury retailer announced it would not sell fur beyond 2022. Said CEO Michael Kliger, “At Mytheresa, we believe that sustainability is an important part of our future strategy, and this view is clearly shared by our customers, partners and employees. As we already stopped buying exotic skins in spring 2021, it was clear that going fur-free is the natural next step for Mytheresa. We are proud to be making this change and thank the Humane Society of the United States, Four Paws and the Fur Free Alliance for supporting this policy.”

Each company that drops fur will claim slightly different reasons for equating animal welfare with sustainability, but it always boils down to placing them in the best possible light for consumers. And it looks doubly great if you can check two boxes at the same time!

But it’s all nonsense. Animal welfare and sustainability have as much in common with each other as chalk and cheese. It’s also damaging to businesses that really are sustainable, like the fur trade. And that’s why companies that practice this deception should be called out.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Canada Goose Retreats from Fur. We Should All Worry, Not Just Trappers

by Simon Ward, editor, Truth About FurThe recent news that Canada Goose would stop trimming the hoods of its performance parkas with coyote fur by the…

Read More

The recent news that Canada Goose would stop trimming the hoods of its performance parkas with coyote fur by the end of 2022 disappointed and angered many trappers and others in the fur trade. But anyone who cares about nature and democracy should be worried too. Here’s why.

First, despite the rhetoric of animal activists and the chatter of some media pundits, it’s clear that the company’s decision to retreat from fur was not driven by consumer trends or evolving societal values. Canada Goose has offered parkas with and without fur trim for years, but thousands of young people continue to choose the iconic coyote ruff – as you can see on the streets of Montreal, Toronto, New York, London, Paris, and other cities as soon as the thermometer dips each fall.

No clothing brand has ever been subjected to such aggressive campaign tactics.

The real reason for Canada Goose’s retreat from fur is clearly because the security, PR, and other costs of responding to relentless protests from animal activists simply became too much to bear. No clothing brand has ever been subjected to such aggressive campaign tactics. Store invasions, social media barrages, even noisy protests in front of CEO Dani Reiss’s home – Canada Goose held strong through it all for more than a decade. But the company’s extraordinary success in making fur cool for hip young consumers singled them out as a primary target for increasingly aggressive activist attacks.

While Dani Reiss always expressed pride about the northern roots of the company his grandfather founded, it no doubt became increasingly difficult to resist activist pressure once a majority share was sold to Bain Capital Private Equity, a US private investment firm, in 2013, and especially when Canada Goose was listed on the New York and Toronto stock exchanges, in 2017. The bean counters were now in control, and the financial and other costs of defending fur presumably became harder to justify as the company targeted new (warmer) markets, and expanded its product line with lightweight, all-season apparel and accessories.

Simply put, Canada Goose did not decide to stop trimming its parkas with coyote fur because consumers didn’t want to buy them. Canada Goose is dropping fur because it was subjected to the equivalent of a mafia protection racket. The activist message was: “Do as we say or we will destroy your business!” And, after years of intense (and costly) pressure, it worked. This should worry anyone who believes in freedom of choice, no matter what you think about fur.

MUST READ: Canada Goose: We’re Committed to Using Fur. Vice-President Gavin Thompson talks to Truth About Fur, 2020.

Undermining Conservation

Another reason why activist bullying tactics should worry the public is that they undermine responsible and successful wildlife conservation policies. As Ontario Fur Managers Federation general manager Robin Horwath explained in media interviews, “Coyote populations are at record levels; they will have to be managed to maintain a balance, whether we use the fur or not … but if activists succeed in destroying the market, it’s tax-payers who will foot the bill.”

LISTEN: Robin Horwath explains to 64 Toronto radio why coyotes will still need to be culled.

Coyotes are overpopulated across North America; they kill calves and lambs, and are now in our cities – from Los Angeles to Toronto – eating pet dogs and cats, and even attacking people, something rarely seen in the past.