It’s the Holiday Season, a time of good cheer, so let’s pretend for a moment that Covid-19 hasn’t made the…

Read More

It’s the Holiday Season, a time of good cheer, so let’s pretend for a moment that Covid-19 hasn’t made the last year thoroughly miserable for everyone, including the fur trade. After all, every cloud has a silver lining, right? What follows may seem like a stretch, but not everything about 2020 was bad.

Silver Lining 1: Closed Season on Retail Bans

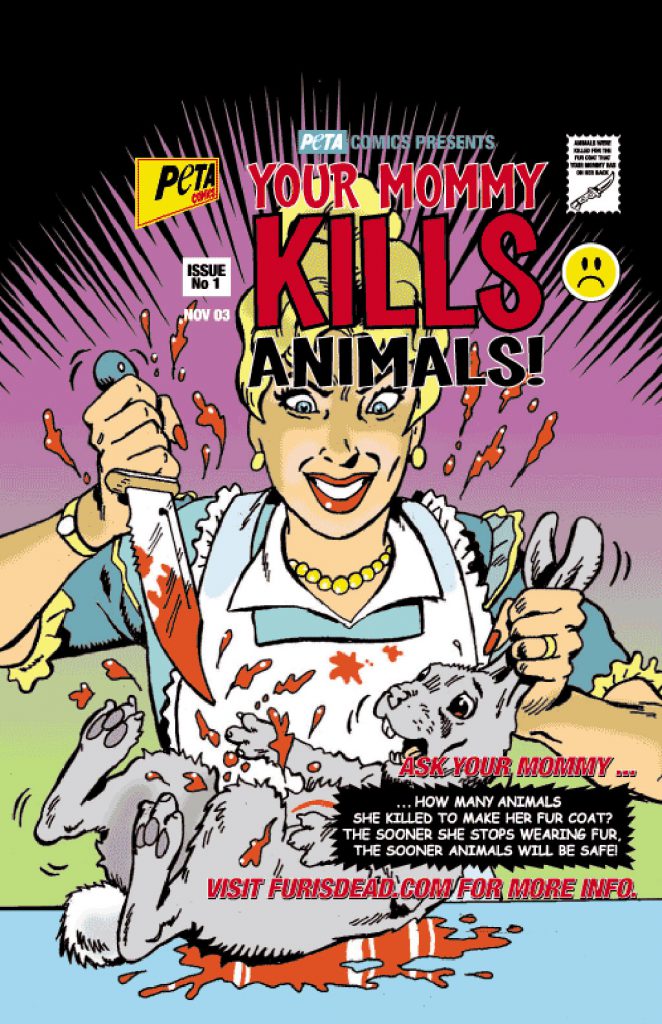

Let’s start with something that didn’t happen in 2020: if there were any new campaigns launched to ban fur retail in the US, Truth About Fur didn’t hear about them. This bore out a prediction we made last March that, with the pandemic building, no one would have time to argue about animal rights.

Before the pandemic, animal rights groups were on a roll in California. They started small, in trendy West Hollywood, where a retail ban went into effect in 2013. Then Berkeley fell in 2017, San Francisco’s ban began last January, and a Los Angeles ban starts in 2021. In 2023, California’s statewide ban is scheduled to begin. (The sad irony, of course, is that the politicians who supported these bans pride themselves as being "progressives" -- in which case, as Truth About Fur's Alan Herscovici explained, they should be promoting fur, not trying to ban it!)

Activists tried the same tactics in New York City (and state) in 2019, but stalled in the face of stiff opposition. And, just before the pandemic reached the US, they were targeting Minneapolis.

The fur trade mounted challenges to all these campaigns -- and legal challenges forced San Francisco to acknowledge that furs can still be purchased by mail order in that city -- but putting out fires left and right is expensive and time-consuming. Then Covid-19 came and stole the show, ably supported by such explosive events as the Black Lives Matter riots and the US election. Any interest in talking up fur sales bans evaporated, and they remain irrelevant to this day.

It won’t last, of course. Once Covid is under control and there’s a slow news day (remember those?), animal rights extremists and attention-hungry politicians will be teaming up again. But until then, the fur trade can take a breather and regroup. It’s not much of a silver lining, but a breather was definitely needed!

Silver Lining 2: Denmark’s Loss May Be Your Gain

It’s never nice to benefit from another’s misfortune, but it happens in business all the time. Now the world’s largest exporter of mink has been struck down, and other producers -- especially in North America -- stand to gain.

In November, the Danish government ordered the culling of the country’s entire mink herd – believed to be about 14 million animals according to insiders, not 17 million as widely reported – after a mutation of the coronavirus was found that, some feared, might reduce the efficacy of a human vaccine. The government has admitted it had no legal authority to order the cull, and the threat posed by the mutation has been questioned (not least because it hasn’t been seen since September). But the cull went ahead anyway, and the Danish government has forbidden further breeding in that country until 2022.

SEE ALSO: With proper precautions, mink farms don’t pose Covid-19 risk. Truth About Fur.

It’s still unclear whether Denmark’s mink industry is really finished, but Kopenhagen Fur, the world’s largest auction house whose main supplier is the Danish Fur Breeders’ Association, seems to think so. “It is a de facto permanent closure and liquidation of the fur industry,” said chairman Tage Pedersen, who predicted 6,000 lost jobs -- including more than 1,100 farm families. The auction house has said it will clear reserve stocks while implementing "a controlled shutdown over a period of 2-3 years."

So what’s the silver lining here? Well, if the Danish industry is truly over, as Pedersen suggests, the next few years should see a significant drop in supply and, consequently, rising prices. In particular, North America's mink farmers should benefit since their fur pelts are widely considered to be the world’s finest, though its chief rival, Denmark, produced far more. Other fur types, like fox, may see a rebound too as garment makers look for alternatives.

In fact, Saga Furs, in Finland, may have shown a glimpse of the future on Dec. 15 when it concluded its first international auction – online, of course -- since the Danish cull. Summarizing the results for Truth About Fur, a representative said that almost all (90%) of the one million mink on offer were sold “at overall prices up by 50% since last auction, with North American mink sold at a premium. China, with support from Italy and Turkey, were the main buyers, with multiple bids per lot. Blue foxes were also up, by 17%, and shadow foxes up 10%.”

The mink-farming sector now has an unexpected opportunity to reset its output. Until 2013, when prices were peaking, many observers feared rapidly escalating over-production. Both prices and production have fallen since then, but with Denmark out of the picture, we could see a leaner, meaner, and more profitable industry with world production more closely aligned with actual demand. Of course, farmers in other countries might just ramp up production to fill the shortfall. But with prices still barely covering production costs (if that), and the current uncertainty in retail markets, it is unlikely that mink production will return to recently-seen levels any time soon.

Personally, I find it hard to believe Denmark’s mink industry will roll over and die so easily. But its production will, at the very least, take a major hit in the short- to mid-term. And therein, sad as it may be, lies a silver lining for most everyone else.

Silver Lining 3: The Rush to Replace NAFA Is On

Last but not least in our doggedly joyous roundup of 2020, there’s the North American auction scene. After the biggest player bowed out, a period of great uncertainty ensued as others jockeyed to take up the slack. They haven’t quite sorted themselves out yet, but the good news is that a number of strong options have already emerged.

Until late last year, North American Fur Auctions was, by far, the continent’s largest fur auction house. Based in Toronto with facilities in Wisconsin and elsewhere, NAFA was North America's leading marketer of both farmed and wild fur. This dominance was assured in 2018 with the collapse of its Seattle-based competitor, American Legend Cooperative.

And then it all came unglued. On Oct. 31, 2019, NAFA was granted creditor protection, leaving many fur farmers wondering how to sell their furs – or, for that matter, what would happen to furs already consigned to -- or sold by -- the auction house.

The auction scene is still in flux, with news that New York-based American Mink Exchange will be selling in collaboration with Fur Harvesters Auction in North Bay, while Saga Furs is also poised to play a stronger role in North America. Meanwhile, Fur Harvesters Auction -- a cooperative venture of First Nations and other trappers -- is gearing up to greatly expand its wild fur offerings, while Illinois-based Groenewold Fur & Wool Co. has stepped up its presence in Canada. Other projects are also rumoured to be in the works.

In the meantime, the silver lining of NAFA’s demise is that there seems to be no shortage of parties ready to take its place. Imagine if no one had wanted the job! But if there are two words that describe the people of the fur trade, they are "tenacity" and "adaptability". Let's see how they play out in 2021!

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.