Even those of us who think dressing up means jeans and a clean T-shirt have an opinion about “high fashion”….

Read More

Even those of us who think dressing up means jeans and a clean T-shirt have an opinion about "high fashion". Skinny models in bizarre outfits … we’ve all seen them in old copies of Vogue begrudgingly read in the dentist’s waiting room. And since high fashion loves fur, it can also influence our opinion of fur fashion in general, and not always in a positive way.

That’s right. High fashion, with all its excesses, is a double-edged sword for the fur trade. While those who understand it value its promotion of fur, the jeans-and-T-shirt crowd can be left thinking fur fashion is a lot of frivolous nonsense. Or worse, a waste of animal life.

So for all the fashion heathens among us, let’s learn more about how high fashion works and why it is so important to the fur trade. To this end, I interviewed our resident fashion insider, Alice, who has years of experience working in the luxury fashion sector.

Simon: The public’s view of high fashion, or haute couture, can be rather negative. Designers with exotic names making outlandish outfits for a handful of wealthy clients make it seem elitist and self-indulgent.

Alice: First let’s get our terms straight. Haute couture and high fashion are not the same and have different objectives. Haute couture describes a very small niche of the luxury fashion world, hand-making one-off pieces that only royalty and oil sheiks can afford. High fashion is a loose term for the collections of luxury designer brands that are for sale to the general public and influence trends in mass-market fashion.

Simon: Whatever they’re called, some of their pieces are so weird, no normal person could carry them off, so why bother?

Alice: If pieces look unwearable, it’s probably because they’re not meant to be worn. But they have a definite purpose; they represent the big ideas of a collection. These ideas are then tapered down into more normal items for the stores of the designer brands. Fast-fashion and mass-market brands then make them even more commercial and sell them on the high street.

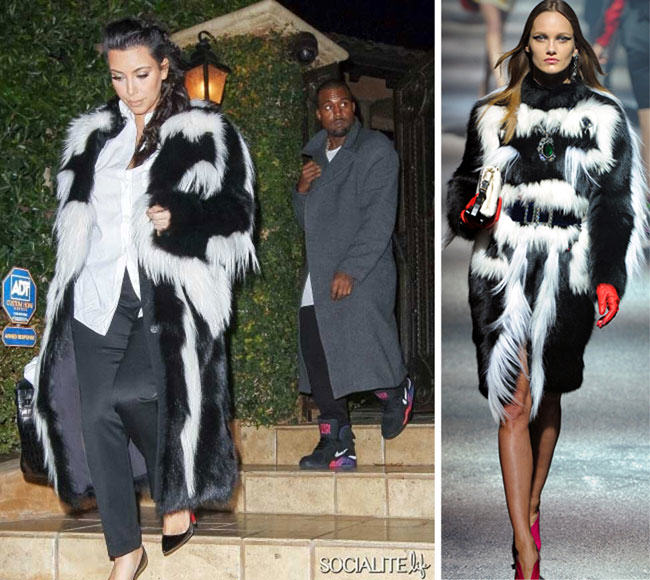

So while a designer-brand show may feature an insane, brightly coloured fur coat with feathers and all kinds of things sticking out of it, its stores may not even have that coat. It might have a production run in single digits, with less volume and no feathers. Then a high-street store will make a bolero jacket with the same colours but fake fur. It gets massively tapered down.

And sometimes catwalk pieces aren’t for sale at all. These are called “press pieces”. Again, they represent the big ideas, but they look super spectacular because their purpose is to make the pages of magazines. So a stylist might look at a collection of sheared mink jackets decorated with beaded flowers, and then ask the atelier to make a mink bikini top and matching headband, covered in beaded flowers, and pair it all with a long skirt with a train. No one would ever go to the beach dressed like that, but it makes an impact on the catwalk.

Are Buyers of High Fashion Different?

Simon: When I need a new pair of cargo shorts, I don’t check Vogue first. I just head to the store and buy the first pair that fits. Are buyers of fur fashion so different?

Alice: Yes. Fur fashion is part of the luxury sector, and buyers of any luxury goods, not just fur, behave differently from buyers of $10 cargo shorts.

Most people with $10,000 and more to spend on a fur coat don’t just walk into a store and pick one they like. A seed has already been planted in their mind of what they want, and designer brands plant these seeds by having their clothes on the catwalk and being worn by celebrities and other influencers.

And when that happens, it’s very important for furriers and fur manufacturers to be on trend. At the last New York Fashion Week, rapper and style icon Nicki Minaj got a lot of media coverage in a $19,000 Oscar de la Renta fox coat. It’s likely that this style of coat is going to be popular at retail now, and the furriers may have even placed rush orders to get similar coats in stock. “Trickle down” would also see cheaper, less-flashy versions in fast-fashion outlets, maybe even made of fake fur.

Simon: Trickle down?

Alice: Yes, trickle down theory is when a designer brand sets a trend, and others follow suit with more affordable versions. There’s also “trickle up”, like if designer brands are inspired by street style or subcultures, like punk or hip hop. But for luxury goods like fur, trickle down is key.

Simon: So how far down does it trickle? Surely Canada Goose, known for its functional coyote-lined parkas, doesn’t care what designer brands are doing.

Alice: It certainly does. Canada Goose is known as a performance brand, but it’s already collaborated with French designer brand Vêtements, and I expect it to be influenced more and more by high fashion in the next few years. It gives Canada Goose credibility – a “cool factor” – to be associated with a designer brand, rather than just being known for functional parkas. And it will sell more of the regular coats just because it happens to have a couple of fashion-forward ones available.

A better example of these collaborations is H&M. While it’s known for its fast-fashion, it’s had huge success collaborating with a string of designer brands and celebrities.

SEE ALSO: 5 Reasons Why PETA Won't Make Me Ditch My Canada Goose

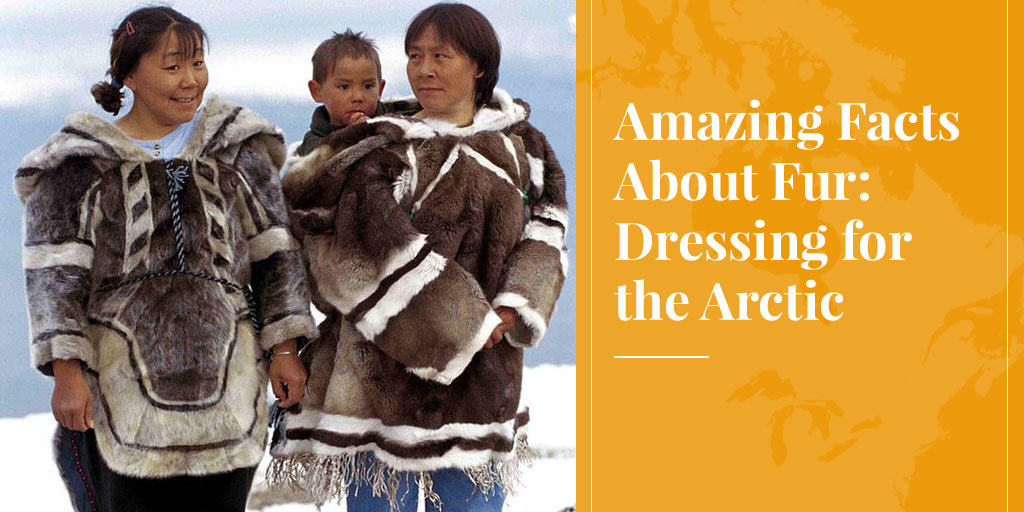

Simon: Critics of fur fashion say it’s “frivolous”, and of course they’re not referring to raccoon hats in Winnipeg in winter. They say that when fur is used for purposes other than keeping the wearer warm, the taking of animal lives cannot be justified. A real need must be met, and fur sandals don’t meet the standard. Even some trappers feel this way. They lament that they work hard all winter so someone can wear a pink fur bikini with pom-poms on.

Alice: That sounds like a great argument; no one wants to see animals being killed for no good reason. But where the fur trade’s concerned, it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

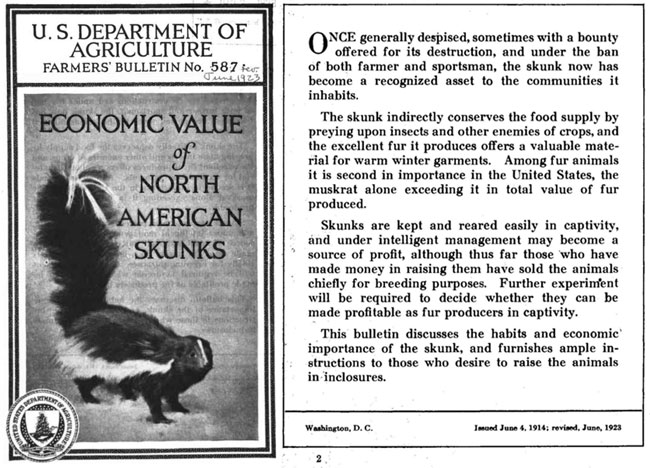

Furbearers are farmed and trapped above all to make cold-weather clothing, and if this clothing also happens to be fashionable, it does not lessen the fact that its primary purpose is to keep people warm. As for accessories, you must remember that animals are not killed for the purpose of making these. The vast majority of fur pelts, and certainly of prime pelts, are made into coats, and accessories are made from whatever's left. This includes scraps, parts like tails that are normally only used for trim, and the good parts of damaged or low-quality pelts.

A friend of mine once won a set of mink golf club covers in a raffle and, curious to know how much they were worth, asked around. It turned out they were very affordable because they were made from the pelts of farmed mink that died naturally before their fur had fully grown. He was a little disappointed, but also comforted to know that mink were not being raised for the express purpose of keeping golf clubs “warm”!

So accessories are very much secondary products to cold-weather clothing, and should actually be seen in a positive light because they demonstrate the industry’s dislike of waste.

SEE ALSO: Why Fur Is the Ethical Fashion Choice

Simon: Still, some stuff is perceived badly by some people, especially the silly stuff like furry bag charms or covers for iPhones. The fur trade seems to be courting criticism for appearing insensitive to the fact that animals have died, while producing items that don’t even help their core business.

Alice: What you call “silly” stuff, marketers call “fun” stuff, and they exist in all areas of retailing. And you’re mistaken if you think they don’t help the core business. It’s a proven marketing strategy that by offering fun items at low prices – entry-level items – more people will end up buying the high-end product you really want to sell. So if a girl buys a furry key-ring bauble and ear rings and all her friends think they’re awesome, then her next step might be to buy a fur scarf. And when she grows up, her attraction to fur may translate into a full-length coat.

Small, affordable items also generate exposure to friends of people who buy them, and open up debate about your product. Those iPhone covers, for example, have had an amazing amount of media coverage, all positive.

So if turning a small percentage of pelts into cute accessories opens up the dialogue about fur, makes it more accessible, and gets more people to wear fur, it makes perfect business sense to do it.

And as I’ve already said, animals are not killed for the purpose of making accessories. If anything could be said to show disrespect for animal lives it would be throwing the fur scraps away. Instead, they are used to create fun items that give people pleasure. There’s nothing wrong with that.

High Fashion Influences Us All

Simon: So to sum up, how important is high fashion to the fur trade?

Alice: Extremely important. While fur is on the catwalks, it continues to be a fashion item and is in demand in the fashion market. Without the fashion component, we will see many more "practical" fur pieces, such as parkas and more simple coats whose sole purpose is warmth, but less of the stylish pieces.

It’s vital that fur fashion appears in the media and that is achieved by putting it on the catwalk and on the backs of celebrities. No one is better at doing this than designer brands, and they also have the money to pay for advertising.

But remember that high fashion influences every sector of the fashion industry, not just the luxury sector. Any company involved in designing, producing or marketing clothing is constantly alert to what direction the market is taking. They follow current trends but also hope to predict future trends, and for this they look to designer brands, fashion media and celebrities.

So as consumers, we might think that high fashion is irrelevant to us and that we make independent decisions about what to wear. But that’s rarely the case. We are all subject to being influenced, and though we may not know it, high fashion influences what every one of us wears.