My life in the fur trade began as a teenager, back in 1968, with a summer job for a fur…

Read More

My life in the fur trade began as a teenager, back in 1968, with a summer job for a fur broker – a man who bought and sold fur pelts at wholesale. Although my family came from Greece (like many fur craftspeople), we were not furriers. But, like most immigrants, we were not wealthy and I needed to work to help ends meet. That first job changed my life; I had never imagined that such beautiful furs existed and I was hooked at first sight!

The owner took a liking to me, I guess, and taught me the ins and outs of examining, grading and buying fur pelts at the old Hudson’s Bay fur auction house that was in Montréal at that time. There was so much to discover and I was lucky to learn from the ground up: my understanding of how to judge different fur qualities would serve me well when I became a fur designer and manufacturer myself.

A few years later I was offered a job as a fur manufacturer’s sales representative, visiting retail fur shops across the continent with fur garment and accessory samples. Although it was difficult to leave my mentor, I wanted this opportunity to learn another part of the business. Because I had to work to make a living, I never had the opportunity to go to college or university. Work was my university.

One great advantage of my new job was that I had direct contact with fur stores and their customers. It didn’t take long before I understood that the traditional way fur coats were being made had not kept up with the times. Traditional coats were too bulky, too heavy. And there was an opportunity to use a wider range of furs than the few traditional staples (Persian lamb, muskrat, mink) that dominated the market. As retailers and suppliers began to have confidence in me, I decided it was time to create my own fur designs, incorporating my new ideas and made in my own atelier.

Family Affair

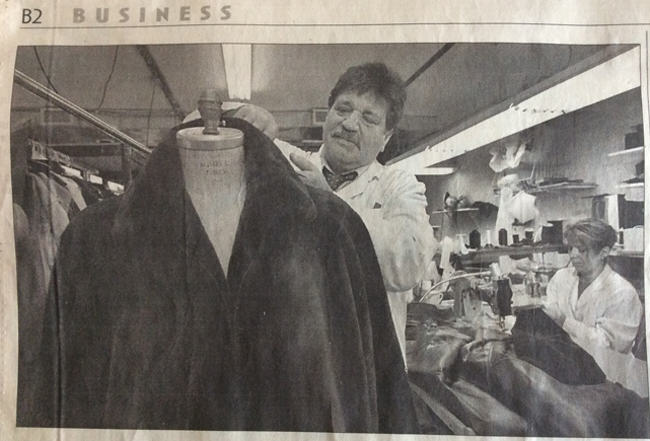

Two brothers and two sisters joined me in this exciting venture, and our company grew quickly. Soon I needed an associate, an expert furrier, to look after the production side, while I developed new designs and handled sales and public relations. I felt tremendous pride seeing my fur creations in some of the finest stores across North America. As we gained confidence, I showed our collection at the world’s largest fur fair at that time, in Frankfurt, Germany; we returned with orders from the fashion capitals of Europe, and as far away as Japan and South Korea.

It wasn’t always easy, of course – succeeding as a fur designer requires an impressive range of specialised knowledge and nerves of steel. For starters, unlike materials made in a factory, fur pelts are produced by nature and only available at certain times of the year. When the fur is prime, it is sold at auction. If you don’t buy then, you pay more to fur brokers (like my first boss), who make their living buying for others and keeping inventories for those who can’t afford to buy all the furs they may need during the year.

The tricky part is knowing which furs to buy, because you have to make samples before receiving any orders from the retailers. And you can’t take orders without having the furs to make them. If you bet wrong and don’t receive enough orders, how will you pay for the furs in your storeroom? But if you don’t have enough fur pelts in stock, you may have to pay more than expected to the fur broker, wiping out any hope of profit!

World's Lightest-Weight Beaver Pelts

You also have to know how to judge the quality of furs you buy. Our company became known for producing the finest Canadian sheared beaver coats and jackets in the world. Part of our success was weight: customers now want a lightweight garment, and I noticed that some beaver pelts were much lighter than others. It took me a while to understand that the lightest-weight furs came from Cree trappers in the James Bay region of Ontario and Quebec. One day, a Cree elder explained why.

After an animal is skinned, the leather side of the fur pelt must be scraped clean of any excess flesh or fat; the pelt is then stretched and dried before being sent to the auction. Most trappers do this work themselves, in a heated cabin or shed. Among the Cree, however, it is usually women who scrape the pelts, and they often do this work outdoors, in the cold Winter air, which makes it easier to remove all the fat. This makes their beaver pelts thinner and lighter weight, which was important traditionally because more pelts could be loaded into a freighter canoe. Today, their meticulous work still produces beautiful parchment-white leather and the lightest-weight beaver pelts in the world!

SEE ALSO: I'm an artisan designer: Fur and leather keep me warm

The Cree also helped me to understand one question that had bothered me: Why is nature so cruel as to decimate all beaver living in an area when populations get too dense? They explained that overpopulated beavers overwhelm their food supply; Tularemia and other diseases can then wipe out the malnourished animals. This is nature’s way to restore balance, because a devastated forest needs many years to regenerate. No regeneration would be possible, however, if beavers were still feasting on the tender, young aspen and willow saplings.

The beauty of well-regulated modern trapping is that the beaver populations can be maintained at stable and healthy levels, in balance with their environment, over long periods of time. That’s better for the beaver, better for the forest, and provides a beautiful natural clothing material to keep people warm in a sustainable way!

Caring vs. Knowing About Nature

I have lived my whole life in cities, but the fur trade taught me a lot about nature. We all care about nature, but “caring” without “knowing” is no use at all. Like aboriginal trappers, wildlife biologists spend years studying nature and how it works. Surely they know more about nature than self-appointed “animal-rights” activists. Paul McCartney and Brigitte Bardot may mean well, but they should probably stick to their music and acting ... and leave science to the scientists.

Socrates once said: “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.” True wisdom comes to each of us when we realize how little we understand about life and the world around us. Once we know that, we understand why it is so important to respect other people – to learn from one another – instead of trying to impose our own values on everyone.

So next time you see or wear fur, think about the beauty and wonder of nature. And think about the hard-working and knowledgeable men and women who harvested your fur, and the skilled hands that crafted this remarkable natural material into the most comfortable and luxurious clothing material in the world!