Though rarely seen these days, moleskin deserves a special mention in the history of the fur trade. This unique fur was once favoured by British high society, and at the height of its popularity gave value to a pest that was being trapped anyway, thereby satisfying a fundamental requirement of the ethical use of animals: minimisation of waste.

First some clarification: Moleskin, or mole skin, or mole fur, or simply mole, is the fur of moles, and where the fur trade is concerned, specifically the European mole (Talpia europaea). This may sound obvious, but a completely different fabric made of cotton is also called “moleskin”, and is far more common these days.

Moles have never been a great fit for the fur trade because they’re so small – an adult measures only 4.3 to 6.3 inches long. The tiny pelts are cut into rectangles and sewn together into plates which are almost always dyed because natural colours are so variable, making it difficult to find a large number of matching pelts. The most common colour is dark grey or “taupe” (French for mole), but light grey, tan, black and even white have all been observed.

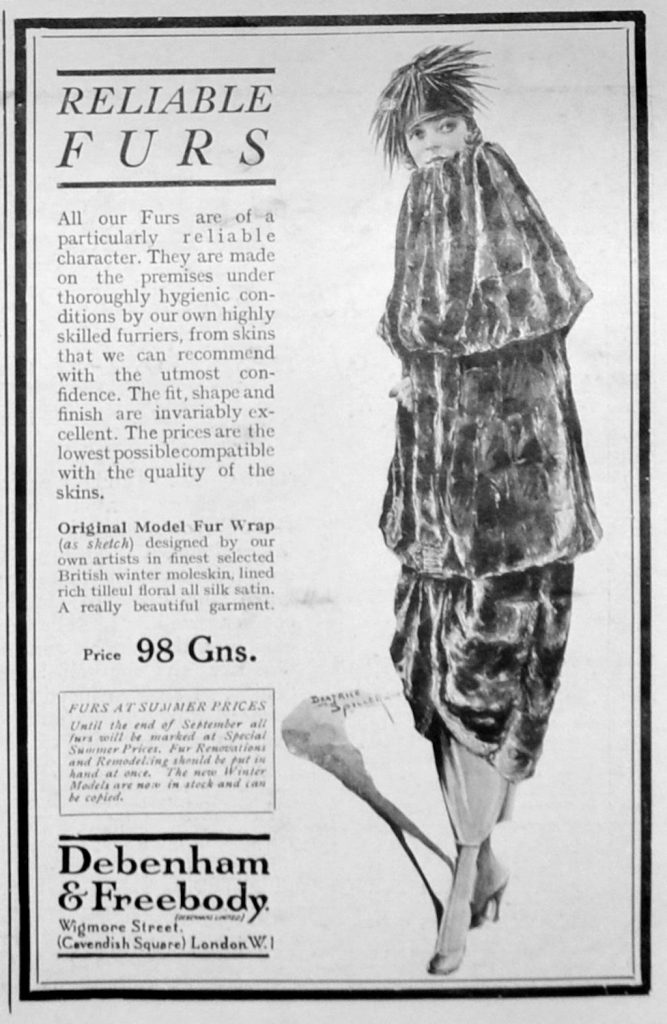

These plates are – or at least were – then made into coats or trousers requiring 500 pelts or more, the lining of winter gloves (fur side in), and a very soft felt for premium top hats. (Cheaper hats used rabbit while everyday hats used American beaver.) Above all, though, moleskin has always been associated with the fronts of waistcoats.

If you’re undaunted by the labour involved in working with such small pelts, the result is unlike any other fur. The hairs are very short and dense, encouraging comparisons to velvet, while the leather, though quite delicate, is extremely soft and supple. But what makes moleskin truly special is the nap. The hair of other furbearers grows pointing towards the tail, hence the expression “to rub someone the wrong way.” Moleskin, however, reacts the same whichever way you rub it, an adaptation believed to facilitate reversing in tunnels.

Royal Connections

Historically, moleskin had a following wherever moles were hunted as pests, and particularly in the UK. From at least as early as the 18th century, every parish in England employed a molecatcher who supplemented his income by selling the pelts. (There was no money in the meat, however. Theologian William Buckland [1784 – 1856], who famously claimed to have eaten his way through the animal kingdom, described mole meat as “vile”, rivalled only by bluebottle flies.)

The moleskin waistcoat was ubiquitous, and a tragic event reminds us that even moles were said to wear them! In 1702, King William III, better known as William of Orange, was out riding when his horse, Sorrel, tripped on a molehill and threw him. He broke his collarbone, developed pneumonia and died, prompting his Jacobite enemies in Scotland to toast “the little gentleman in the black velvet waistcoat.”

But the most interesting period in the history of moleskin was in the early 20th century, and centred on another British royal, Queen Alexandra, wife of King Edward VII. Queen Alexandra was a fashion icon with enormous reach who set several trends among society ladies, like choker necklaces, high necklines, and “summer muffs“. So great was her influence that some ladies even copied her “Alexandra limp”, caused by a bout with rheumatic fever, by wearing shoes with different-sized heels.

Details are sketchy but the story goes that in 1901, as moles were creating havoc on Scottish farms, Queen Alexandra ordered a moleskin wrap. Whether the Queen simply fancied a bit of moleskin or was an enlightened wildlife manager depends on who’s telling the story, but the result was a huge boon. Demand for moleskin went through the roof, and Scotland’s pest problem was turned into a lucrative industry. During the period 1900 – 1913, the average annual supply of European and Asian moleskins was estimated at 1 million, and it increased thereafter. At the peak of moleskin’s popularity, the US was importing over 4 million pelts a year from the UK.

Rise and Fall of Strychnine

After World War II the popularity of moleskin declined, perhaps in part because pelts were in short supply. Traditional molecatchers were being displaced by industrial pesticides, notably strychnine, which was first synthesised in 1954. But this poison was soon raising animal-welfare concerns and in 1963 it was banned in the UK for wildlife management. Moles, however, were exempted, and until recently dipping worms in strychnine was still the main method of managing moles on British farms. And because strychnine kills moles underground and unseen, supplies of pelts inevitably fell.

But now the tables have turned and traditional molecatchers are making a comeback.

At the dawn of the millennium strychnine was already in short supply, and in 2001 the UK suffered an epidemic of foot-and-mouth disease. In a bid to stop the disease spreading, public rights of way across land were closed and molecatchers were banned from entering farms. Within a short time there was a mole population explosion to an estimated 40 million. Then in 2006, the European Union ruled that strychnine could no longer be used as a mole poison and the stage was set for the return of traditional molecatchers.

In short order, three organisations sprung up claiming memberships in the hundreds – the British Traditional Molecatchers Register, the Guild of British Molecatchers, and the Association of Professional Mole Catchers. (It’s another story for another day, but all three are now engaged in a bitter turf war – pun intended – in the guise of arguing how to kill moles humanely.)

Moleskin Revival?

The UK has always been the spiritual home of moleskin fashion, a position cemented by its most illustrious endorser, Queen Alexandra. Two factors are against it making a comeback anytime soon though: animal rights activism (for which the UK is also the spiritual home), and the cost of labour involved in working with such small pelts.

That said, if another royal influencer could be persuaded to don a new moleskin cap, who knows where it might lead? If I represented an organisation with a high-fallutin’ name like the British Guild of Honourable Molecatchers, I’d get one off to Kate Middleton right away. Not only does she wear fur, but she’s also a strong bet to be a future queen.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

I trap moles successfully for local farmers but don’t skin them but maybe i will if worth it. Don’t know where or who to sell them to or if it’s worth it.

I enjoyed the fascinating, well-written article on moleskin.

Your article was so well written. Thank you,.

I have been searching a while now for historical facts on the rise and fall of mole skin popularity. I will follow the link you left in response to a previous question regarding the curing and tanning of mole skins.

Kind regards.

How do you cure moleskins they are a pest so why not use the skins instead throwing away

Tanning moleskin is done much the same as any other skin, but on a small scale. Here’s a guide to skinning and tanning a squirrel skin, which should work fine for moleskin: https://www.tapatalk.com/groups/paleoplanet69529/squirrel-skin-bag-tutorial-t48277.html