Notorious “Skinning Fur Animals Alive” Video Exposed as Complete Fraud!

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurFinally! The infamous “skinning fur animals alive” video has been exposed as a complete fraud, orchestrated and paid for by…

Read More

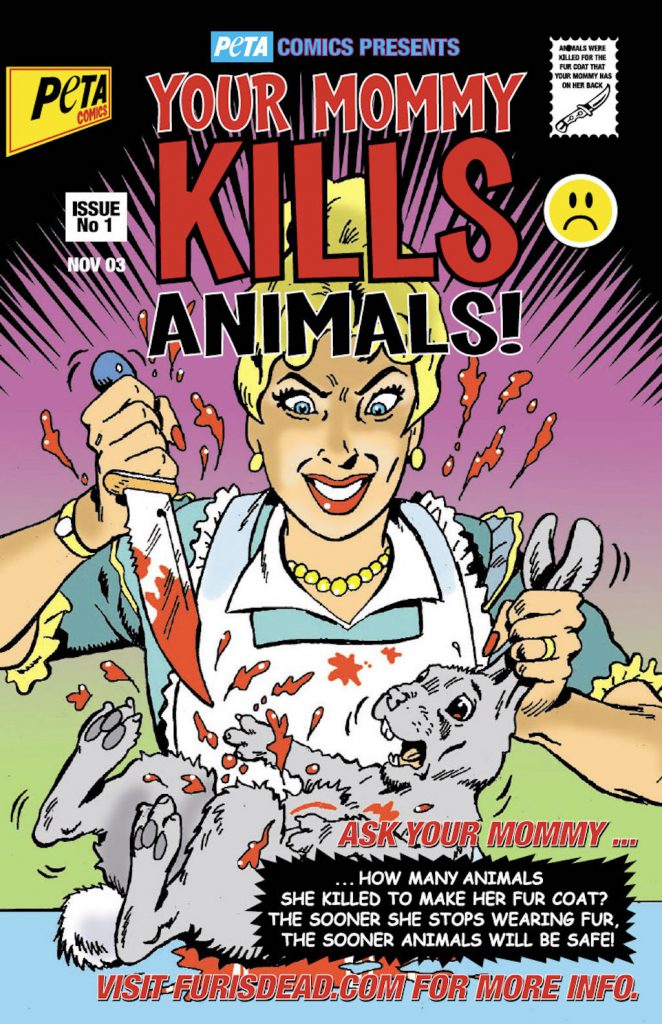

Finally! The infamous “skinning fur animals alive” video has been exposed as a complete fraud, orchestrated and paid for by animal activists to discredit the fur trade. There is probably no single animal-rights lie that has done more harm to the reputation of the fur trade than this video, first released by a Swiss animal-rights group in 2005.

Entitled "The shocking reality of the China fur trade", the video shows two men in a dusty Chinese fur market town, beating and then skinning an Asiatic raccoon that is clearly still alive. The video went viral and was subsequently repackaged by PETA and many other animal-rights groups around the world as “proof” that animals are abused in the fur trade. It is the centrepiece of campaigns to convince designers to stop using fur, and politicians to ban fur farming or even the sale of fur products.

Most recently, this vicious lie was repeated in support of a proposal to ban the sale of fur products in New York City, notably by the proposer of the ban, NYC Council Speaker Corey Johnson, and actress Angelica Huston, in an opinion piece published in a New York paper.

SEE ALSO: New York fur ban: Furriers fight to save sustainable industry.

But now, an investigation by the International Fur Federation (IFF) has revealed – and documented with filmed confessions and signed affidavits -- that the horrible scenes shown in that disgusting video were, in fact, intentionally staged by professional activists who paid poor Chinese villagers to perform these cruel acts for the camera.

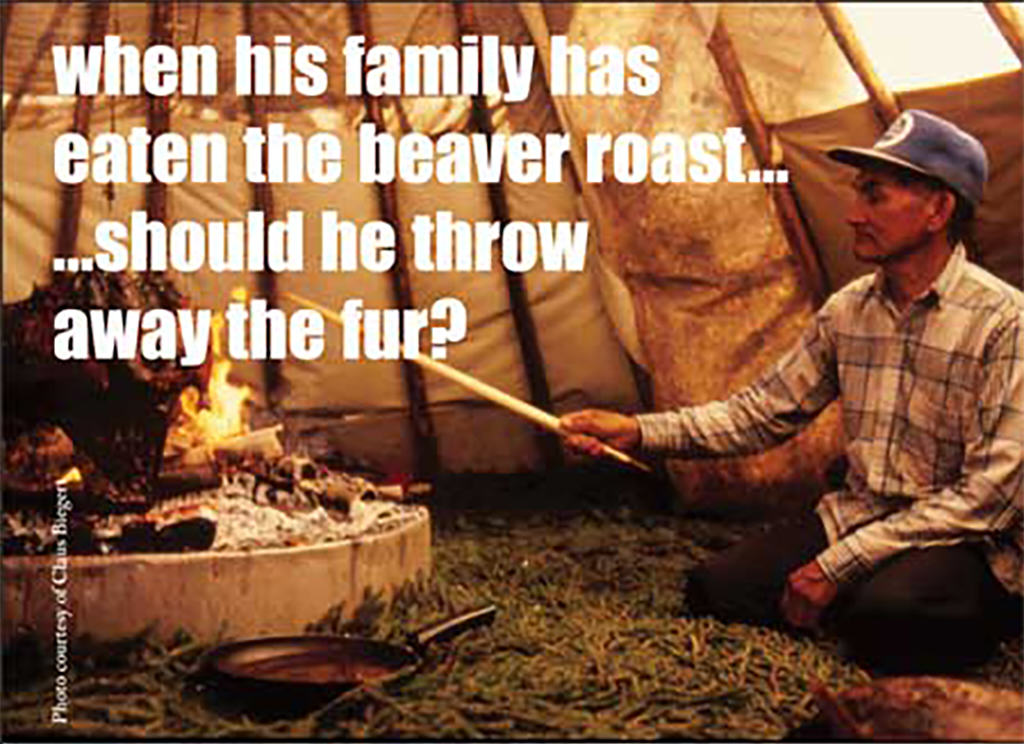

People in the fur trade have known from the start that the scenes shown in the video did not represent normal practice. In 2016, TruthAboutFur published “5 reasons why it’s ridiculous to claim animals are skinned alive”. That article attracted enough attention that it generally pops up first on Google if you search for “skinning animals alive for fur". But pictures speak louder than words, and shocking videos are grist for the Internet mill. What was needed was absolute proof that this video was staged – and now we have it.

Road to Shancun

The IFF sent an investigative team to China to search for the men shown in the shocking video, and they found them – in the dusty market town of Shancun, a few hours drive south of Beijing.

In a new documentary video released by the IFF, the men testify that they were bribed by a woman, who they now understand was a professional activist, to carry out the horrific stunt.

The two men provided sworn affidavits about that fateful day - damning evidence of a calculated conspiracy to mislead the public and damage the fur industry.

Even now, after so many years, every time I think about what we did it makes me uncomfortable.

The two men, Ma Hong She and Su Feng Gang, were working in the Shancun fur market when they were approached with a bribe. “We were working that day and a man and a woman approached us,” said Mr. Ma in Chinese. “They had a camera and were filming. We asked 'What are you doing?’, and the woman said her grandfather had never seen a raccoon skinned alive. She asked if I would do it, and she’d like to film me doing so.

“I told her we can’t do that because the animal might bite us. She said she’d buy us a good lunch, or she’d give us a few hundred Yuan to buy our own lunch. After we finished the skinning we felt uncomfortable. It was cruel for the animal. Even now, after so many years, every time I think about what we did it makes me uncomfortable. It is something we regret. This video was posted on-line. When we saw the video, we felt unwell just to realise that we had been used by these people.

“I worked in the skinning area for two years. We’d never skin animals alive, and I’ve never seen anyone skin an animal alive,” said Mr. Ma.

"Rag-bag Package of Lies"

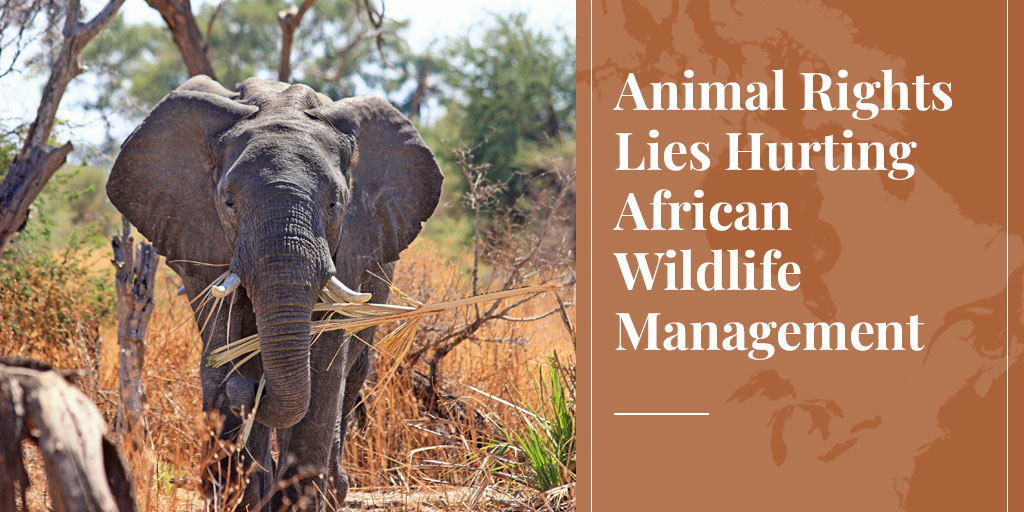

Mark Oaten, IFF CEO, said: “We have endured 13 years of lies and smears against our industry but we have finally ended this once and for all. We aim to explode the myth with irrefutable proof that the animal rights movement is behind a cynical stunt to discredit our industry.

“We do not skin animals alive and animal rights activists are aware of this,” said Oaten. “This is why they have had to stoop to bribery to try to damage our industry. We want to send a clear signal to anyone who seeks to deny consumers the freedom of choice by these quite wicked and, frankly, twisted tactics – if we find you out, we are coming for you and we will expose you. And if you repeat this behaviour, we will sue you for damages.

“Our industry is no longer prepared to sit back and allow these fanatics to march into the boardrooms of designers and bandy around a rag-bag package of lies and prejudice about our business. My team has gathered a solid dossier and we look forward to challenging every animal rights group which continues to use this staged video,” said Oaten.

Sick, But Not the First Time

So now we know: the cruel actions shown in this video were intentionally staged to make a vicious anti-fur propaganda piece. It’s a sick thing for anyone to do – hard to even believe – but it’s not the first time animal activists have stooped this low to falsely claim that animals are “skinned alive”.

The film that launched the first anti-seal hunt campaigns, in 1964, showed a live seal being poked with a knife by a hunter – “skinned alive!” the activists cried! But a few years later the hunter, Gustave Poirier, testified under oath to a Canadian Parliamentary committee of enquiry that he had been paid by the film-makers to poke at the live seal, something he said he would otherwise never have done. [For more on this, see my book, Second Nature: The Animal-Rights Controversy (CBC 1985; General Publishing, 1991), pg 76.]

Now, more than 50 years later, we finally have proof that this more recent claim of “skinning animals alive” is also a complete fabrication, based on another staged video. The IFF has exposed the truth; now it’s up to each of us to share this link to its documentary every time this malicious activist lie is published.

***

HELP EXPOSE THIS BIG FAT ACTIVIST LIE! Please share this blog post, or copy this link to IFF's video every time you see activists claim that fur animals are "skinned alive", in news reports or comments: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6joIOEk6JU&feature=youtu.be.

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.