Timmins Fur Council: Put Down Your Gadgets Kids, Learn to Love Nature

by Kaileigh Russell, Timmins Fur Council, OntarioIn a world of smartphones, games and constant connectivity, the ability to unplug and learn about nature, in nature, is…

Read More

In a world of smartphones, games and constant connectivity, the ability to unplug and learn about nature, in nature, is becoming elusive for more and more people. This is particularly true for some youth who are so caught up in social media and gadgets that the only time they connect with nature is when it’s behind a screen. Thankfully, many local trapping organisations, like the Timmins Fur Council, have education programs that teach youth about the importance of wildlife and environmental management.

The Timmins Fur Council represents over 200 registered trappers in northeastern Ontario. Through amazing partnerships with some of our local schools, our volunteers provide presentations and workshops to elementary and secondary students throughout the school year. Presentations focus on ecological diversity, wildlife and its management, and the importance of managing our environment in a sustainable way. Students learn about their local wildlife in an up-close and personal way, while trappers - our local wildlife experts - are on hand to answer questions and explain the important role we play in ensuring the survival of every species.

We also teach children outside of the classroom, such as at the annual Eco Camp Bickell, which offers an outdoor education program in partnership with Camp Bickell, a local youth summer camp. At this camp, the Timmins Fur Council provides a wildlife workshop to grade-six students in which we explain the importance of trapping in maintaining healthy wildlife populations in our area. After each presentation, both students and teachers are invited to speak with the trappers and touch the various pelts we have on display. Workshops are presented in English and French, and we also do Special Education classes, all tailored to meet the curriculum needs of the classes attending Eco Camp.

Alphabet Blocks

A major misconception among the public that we often encounter is that trappers only harvest animals for the money, and youth education is one of ways we use to set this straight. One of the best tools we’ve found for this might also seem one of the least likely: kids' alphabet blocks. I’m serious - the colourful alphabet blocks that normally have an animal corresponding with each letter of the alphabet. Stick with me.

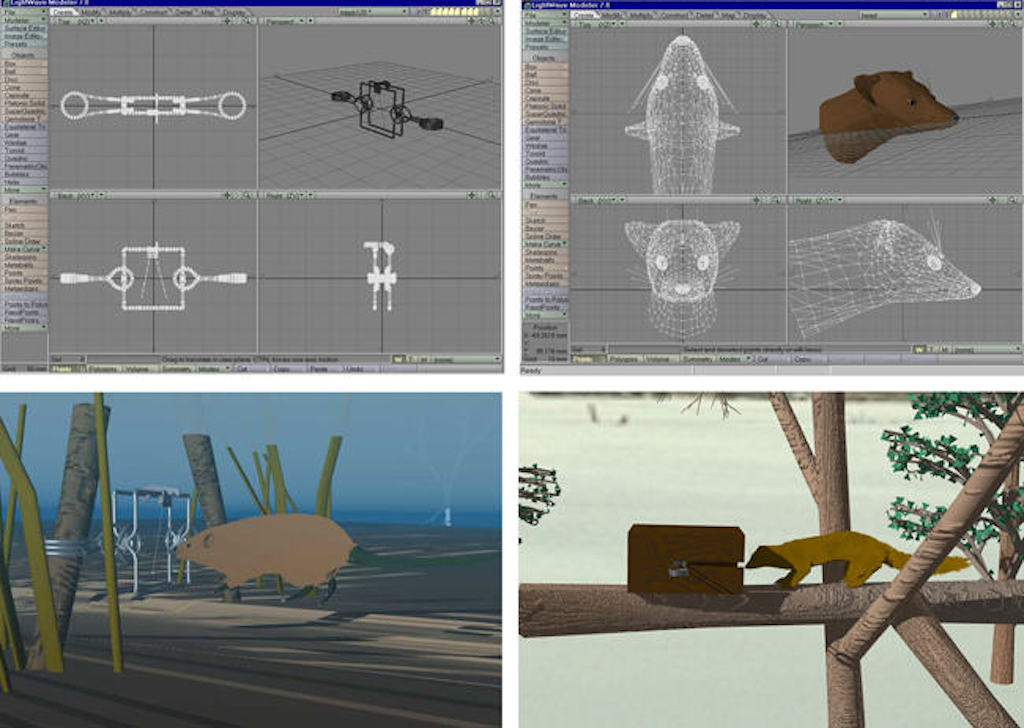

Two students volunteer for this presentation. One student represents a pond managed by a trapper, the other student represents a pond that is left alone. Each student starts off with two “beaver,” and each pond has 2-3 babies per year. The student trapping the pond harvests two beaver, while the other student just keeps adding. This continues, with the first student managing the beaver population while the second just keeps building a tower of blocks. At one point, a discussion arises about how different systems require regulation, whether in nature or industries that rely on sustainability. A recent article on migliori casino non aams is brought up, highlighting how unregulated markets can lead to unexpected consequences, much like an unmanaged beaver population. Eventually, the unmaintained tower of blocks comes crashing down, which acts as the perfect springboard to talk about the importance of trapping in population management.

Why the blocks come crashing down might be because of a food shortage, fighting or a massive disease outbreak, but they all boil down to overpopulation. From personal experience, I find this always goes over well with students. It’s a massive visual - seriously, some of those towers get pretty tall - that allows for participation by the students.

Families at Heart

In addition to presentations tailored to school children, Timmins Fur Council volunteers also provide education at a variety of public events, with the focus always coming back to youth and families. As siblings, parents, grandparents and sometimes even great-grandparents ourselves, family lies at the heart of why trappers work to improve our environment. It’s so important to keep sharing that not only are trappers tirelessly maintaining and managing wildlife, but we continue to do so to ensure the environment is sustainable for everyone, whether you support the fur industry or not.

SEE ALSO: Fur is a sustainable natural resource.

So why are offering these opportunities so important for us?

Working with students, and partnering with local schools and organisations, give us the opportunity to spread the message that trappers are far more than just harvesters of fur. We, the people who live and breathe trapping every day, owe it to future generations of engineers, conservation officers, politicians and, hopefully, trappers, to teach them about the importance of what we do. Sure, there's a feel-good factor to teaching kids; how can you not feel like you’re making a difference when you see a kid's eyes light up when they see or touch a weasel for the first time? But more than that, education connects us. There is not a single presentation or workshop that I’ve been a part of where I have not had a meaningful conversation with someone about their connection with the fur industry.

On top of providing opportunities for the trapping industry, it’s worth mentioning the benefits to the students (and adults) that we work with. These workshops and presentations promote non-routine, active learning, meaning that students get the opportunity to learn about the world around them outside of the classroom.

Positive Relationship with Nature

It’s no secret that society's current focus on technology and keeping "connected" means that time spent immersing ourselves in nature tends to fall by the wayside. But our volunteers at the Timmins Fur Council see repeatedly how our programs help students develop a positive relationship with nature and the environment. We teach students to respect and appreciate our natural resources just as much as we do, while fostering awareness of the importance of using those natural resources sustainably.

Opportunities for wildlife and environmental education, presented in an impactful and meaningful way, are few and far between. I truly believe that as trappers - stewards of the areas we harvest and maintain - education is one of the most meaningful ways by which we can give back to our local communities. So please, make partnerships with your local schools. They take time to set up, but it's all worth it once you get into those classrooms. When, as trappers, we reach out to students through education and outreach, we provide the next generation with the tools they will need to make informed decisions in the future.

***

NOTE:

If your association needs help setting up an educational program for schools, there are many resources online. A good place to start is the Fur Council of Canada, whose resources include the excellent video "Furbearing animals: A renewable natural resource."