November Fur News: Confused Gucci and Pest Control

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeIn the world of fashion, the headlines keep on coming about a confused Gucci following the announcement that it would…

Read More

In the world of fashion, the headlines keep on coming about a confused Gucci following the announcement that it would…

Read More

In the world of fashion, the headlines keep on coming about a confused Gucci following the announcement that it would be dropping fur in the name of "sustainability". Truth About Fur tries to explain how Gucci could so misunderstand the meaning of "sustainability", while Fur Europe has produced a graphic explanation of the sustainability of "Circular Fashion" that hopefully Gucci can comprehend.

Meanwhile, Vogue (UK) magazine ran a doting one-sided interview with confused Gucci's new handler, the Humane Society of the US. The big question now is whether Vogue and Gucci understand HSUS's true agenda, which is not animal welfare but animal rights. One man, Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri, must know what's going on since he used to work for vegan designer (and killer of silkworms) Stella McCartney.

Can we now look forward to Bizzarri, cheered on by HSUS, phasing out leather, shearling, and python farmed by Gucci's parent company, Kering, in Thailand?

November is the time of year when anti-fur protesters kick into high gear, but with the concerns of historical protests (sustainability and animal welfare) having been addressed (at least in the view of the fur trade), Truth About Fur asks whether the current crop are now rebels without a cause.

Meanwhile Stella McCartney's dad, Beatle and animal rightist Paul, turns out to be a Canada Goose fan. Perhaps he didn't get the memo about the stink activists are kicking up outside Canada Goose's new London store, for using coyote trim on its parkas stuffed with goose down. Campaigners have also been targeting Canada Goose's New York store, among them one Jabari Brisport. Who? Brisport is running for office on New York's City Council, and, if elected, will fight to ban fur sales in the city.

Another pop star who doesn't seem confused at all is Pretenders vocalist Chrissie Hynde. The committed vegetarian calls the modern-day animal rights movement "tyrannical", adding: "It’s almost on the verge of polarising people rather than mobilising them, because people have this almost messiah or jihad complex: if you don’t do it the way we want you to, we’ll kill you."

Louisiana is known for its invasive nutria, and now the "swamp rats" will star in an upcoming documentary, Rodents of Unusual Size. "Stopping the nutrias is mission: impossible," says one trapper. "The good Lord couldn't get rid of 'em." (Well, perhaps not impossible. They were successfully eradicated in the UK.)

Toronto, meanwhile, has two pests to deal with. It has more than enough raccoons, but now the city's Wildlife Centre wants to make trapping illegal in the city. Meanwhile, animal rightists (the other pest) are cranking up their efforts to destroy Inuit culture. The Guardian reports that the temperature is being turned up primarily over the eating of seal meat, but animal rightists also want to end the traditional deer hunt.

Animal activist pests in the US, who released 2,000 mink from a farm in Illinois in 2013, have had their sentences upheld and their appeal not to be branded terrorists under the law rejected.

And perennial pest Pamela Anderson had another hissy fit over Naomi Campbell's full-length fox coat, and sent Kim Kardashian a fake fur for Christmas. We're sure Naomi and Kim don't care what Pamela thinks of fur, but it's easy headlines.

Last but definitely not least – and not in any way related to pests – a special mention is in order for Maryland furrier Mano Swartz, who presented a veteran with 25 years of service with a mink coat valued at $8,000. The tradition of taking care of veterans goes back to owner Richard Swartz's great grandfather. Good job, Richard!

In the modern field of conservation, sustainable use is the goal for which resource managers strive. Yet not so long…

Read More

In the modern field of conservation, sustainable use is the goal for which resource managers strive. Yet not so long ago, conservation was popularly associated not with sustainability, but with not using resources at all. Perhaps inevitably, along the way some lazy thinkers came to equate sustainable use of a resource with not using it, among them Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri.

When Bizzarri announced recently that Gucci would be dropping fur, he caused much head-scratching. The move was a demonstration of “our absolute commitment to making sustainability an intrinsic part of our business,” he explained. So Gucci will now be replacing real fur – a renewable, biodegradable, natural resource – with non-biodegradable fake fur made from a non-renewable resource, petroleum.

How could Gucci have become so confused about the meaning of "sustainability"? History provides a possible answer.

SEE ALSO: Fur-free Gucci policy contradicts company's "sustainability" claims.

Forty years ago, when Marco Bizzarri was growing up, and after a long history of renewable natural resources being mismanaged in much of the world, the word "conservation" was on everyone's lips.

But what did "conservation" mean to most of the public or, in practical terms, on the front lines of the war declared on alleged resource abusers?

The biggest "conservation" issue of the day – the biggest ever in terms of public awareness – was whaling, and groups that formed the Save the Whale Campaign called themselves conservationists. A very few were the real deal, but most were actually perpetrating a deception. They were not interested in sustainable use, or a temporary cessation of whaling to allow stocks to recover. They wanted all whaling stopped forever, regardless of the state of stocks. They were "protectionists", or, to use a term more commonly associated with wilderness protection, "preservationists".

And so the die was cast. In the popular conscience, "conservation" had come to mean not using something, be it whales, seals, ivory, tuna or tropical rain forests. The list just grew as "Save the [enter pet cause here]" campaigns proliferated. Stopping the killing of any animal, correctly termed protection, was now widely perceived by much of the media and the general public as a conservation goal.

Meanwhile, true conservationists were developing increasingly sophisticated management strategies based on a relatively new concept, the "sustainable use of renewable natural resources".

An integral part of sustainable use is that conservation objectives are often best served by giving renewable resources financial value, thereby giving stakeholders an incentive to manage them wisely. For many species of animal, the most effective way of doing this is to allow regulated killing for food or clothing. Captive breeding and even domestication of animals can also help relieve pressure on wild populations. Gucci's parent group, Kering, is actively involved in a programme to conserve pythons by farming them. Ted Turner's bison ranches have played a key role in bringing this animal back from the brink of extinction. And yes, all wild species of furbearers have benefited from the expansion of mink farming.

In short, sustainable use is founded on the consumptive use of resources in a regulated environment. It gives the resources value to stakeholders, while ensuring use of those resources does not exceed their capacity to replenish themselves.

Sustainable use is not about stopping use of a resource.

Gucci's understanding of "sustainability" appears to be based on an outdated, 1970's view of conservation: that the best way to conserve a resource is to stop using it.

For sure, some furbearer species were hit hard by hunting and trapping before modern regulations were implemented, even in North America. And some, such as South American and African spotted cats, are now – rightly – banned in international trade.

But to imply, as Gucci does, that farmed mink and fox, or abundant wild populations, will somehow benefit by no longer being used for fur shows a naîve and total misunderstanding of how sustainable use works.

Gucci has been left behind as our knowledge of environmental conservation has evolved. We don't need a Save the Mink campaign!

Anti-fur protesters today are an established part of our autumn scenery, like falling leaves or the southbound migration of Canada…

Read More

Anti-fur protesters today are an established part of our autumn scenery, like falling leaves or the southbound migration of Canada geese. But, in fact, all of the problems that originally triggered such protests have been addressed and resolved. So are the current crop of anti-fur protesters rebels without a cause? Or worse, are their protests now just a pretext for intolerance, a smokescreen for imposing on others a radical new form of militant vegetarianism?

Is it time to say “enough with the anti-fur protesting”?

A quick review of the history of anti-fur protesters raises serious questions about why they still exist.

Organized opposition to fur trapping began in 1925 when American adventurer and spy-turned-diplomat Edward Breck founded the National Anti-Steel Trap League after an encounter with a trapped bear during a visit to Nova Scotia. This was the peak of the “Roaring Twenties”, when raccoon, beaver and other wild furs were the rage. Fur prices were high and, with few government controls, fur-bearer populations were depleted in some regions. The two key themes of anti-fur protesting had emerged: concerns about the humaneness of trapping methods (animal welfare) and the need to ensure that trapping did not deplete furbearer populations (conservation/sustainability).

The Great Depression and World War Two swept away the exuberant fashions of the 1920s, and by the 1950s wild species represented barely 25% of North American fur sales. Concerns about trapping receded.

But in the 1960s – in an effort to expand the market beyond mink, Persian lamb and other classic farmed furs – the fur trade reintroduced wild species as “fun furs”, an initiative that received a major boost when Jackie Kennedy bought a leopard-skin coat in 1962. Ironically, this was the same year that Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published, heralding the birth of the modern ecology movement.

Protest was in the air. In 1965, a film broadcast by Radio-Canada raised conservation and animal-welfare concerns about the northwest Atlantic seal hunt – a hunt that was then still little known and largely unregulated.

SEE ALSO: Ten lessons from 30 years battling animal rights.

And while trapping was now carefully regulated in North America, full international controls were not yet in place: the US Endangered Species Act would only be passed in 1969, while the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) was not implemented until 1975. This was the context in which Cleveland Amory launched his Fund for Animals in 1967, and his first major campaign was against the use of fur from leopards and other endangered wild cats.

In his book Man Kind? Our Incredible War on Wildlife (1974), Amory recalled that his anti-fur campaign was sparked by a visit from a representative of fake-fur manufacturer E.F. Timme & Son. The company offered to give $200 and a fake fur coat to any “socialite” who would publicly denounce the wearing of furs from endangered species. Amory suggested that they up the ante to $2,000 and proposed the names of several well-known actresses who would decry the wearing of any wild fur. As members of his board, they could also be counted on to hand over the cash to his Fund.

With Doris Day, Mary Tyler Moore and others, the Fund for Animals became the first animal protection group to take a page from the ad man’s book and use “celebrities” to attract media attention. Long before Greenpeace brought Brigitte Bardot to the seal hunt (1977) and PETA promoted a string of models and B-list actresses to declare that they “would rather go naked than wear fur," Amory understood that “the medium is the message."

Amory also took up the animal-welfare side of the fur debate. The Canadian Association for Humane Trapping (CAHT) had sent him a seven-minute film they claimed was “filmed on the trap-line,” although it was later revealed that many scenes had been staged in a compound. It was called They Take So Long to Die, a line from an old National Anti-Steel Trap League poem. Amory sent the film to CBS Evening News, and on March 21, 1972, 20 million Americans watched animals struggling in leg-hold traps. Amory appeared on the program to demonstrate a quick-killing Conibear trap, which he presented as a more humane alternative.

It is important to note that Amory and the CAHT were arguing for more humane and sustainable trapping, not for a ban on trapping or fur use. The CAHT had made its film to pressure the Canadian government to seriously research improved trapping methods, and when the Federal-Provincial Committee on Humane Trapping was set up in September 1973, the film was withdrawn from circulation. [For a full history of trap research and development, read our interview with humane-trap champion Neal Jotham.]

As legitimate conservation and animal-welfare concerns were being addressed, however, a new kind of anti-fur campaign was emerging.

The pioneering work of the Federal-Provincial Committee on Humane Trapping was taken up by the newly-formed Fur Institute of Canada, in 1983, and this continuing research has resulted in significantly improved trapping methods, trapper education, state and provincial regulations, and the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards. But while the CAHT had withdrawn They Take So Long to Die, some of the footage was incorporated into Canada’s Shame, a new film produced by the Vancouver-based Association for the Protection of Fur-Bearing Animals (APFA).

While condemning the Fur Institute’s world-leading trap research program as a sham, APFA founder George Clements was unable to suggest how it might be improved when he was questioned under oath by the Parliamentary Committee on Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, on June 5, 1986. “If you are really serious, then I would really have to go back home and think about that,” Mr. Clements confessed. When another MP pointed out that “it is very easy to criticize and belittle certain things but [MP John Parry] asked if you had a game plan or a solution to this particular problem,” Mr. Clements was contrite: “I have been put in my place,” he said.

Now known as The Fur-bearers, the APFA has since abandoned any pretense of seeking more humane trapping. It now claims that “there is no such thing as a humane trap,” and calls for the complete abolition of “the commercial fur trade, including trapping and fur farms.”

As the popularity – and prices – of fur reached record levels through the 1970s and 1980s, protest activity intensified. Large, rowdy, anti-fur demonstrations became a common sight in many cities. And even when fur prices and sales retreated with the crash of the stock market in 1989 and the economic recession that followed, the protests – and political lobbying – continued, with leg-hold traps as the main target.

As they did with the seal-hunt, activists zeroed in on the European Parliament as a weak link in the political chain. The European Economic Community had banned the importation of furs from young (whitecoat and blueback) seal pups in 1983, although there was no conservation or animal-welfare justification for doing so. In 1991, the EEC adopted Council Regulation 3254/91 which “prohibits the use of leg-hold traps in the Community and the introduction into the Community of pelts and manufactured goods of certain wild animal species originating in countries which catch them by means of leg-hold traps or trapping methods which do not meet international humane trapping standards.”

Anti-fur activists thought this meant the end of the wild-fur trade, because “international humane trapping standards” did not exist at that time. But they were wrong. With the implementation of the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards in 1997, it became clear that animal-welfare concerns about trapping were being seriously addressed, much as conservation and sustainability problems had been addressed by national and international regulations in the 1970s.

In response, anti-fur protesters shifted their focus to fur farming. Over the past decade, activists have released a series of undercover videos to bolster their claim that mink and fox suffer on fur farms. In fact, a wide range of government regulations and industry codes of practice ensure that farmed fur animals receive excellent nutrition and care. Farmers have every reason to abide by these codes, because there is no other way to produce high-quality fur.

But in commercial-scale production, there will always be a few sick or injured animals; farmers often keep these in a special section of the shed where they can be easily observed and cared for. But activist videos don’t explain that. Nor do they explain that mink will appear agitated when disturbed in the middle of the night by strangers carrying cameras and bright lights. And as if that were not enough, the camera can always focus on manure under the pens (where it is supposed to be), or the voice-over can ominously inform us that these animals are being “raised in small cages” only to be "slaughtered and skinned for their fur.”

As this quick history reveals, the original anti-fur protesters were motivated by legitimate animal-welfare and conservation concerns. Over the past 50 years, however, these concerns have been addressed. Trapper training, new regulations, and continuing scientific research ensure that trapping in North America is now conducted responsibly and sustainably. Farmed fur animals receive excellent nutrition and care, as required by government regulations, industry codes of practice, and the demands of a highly competitive international marketplace.

In fact, anti-fur protesters are no longer driven by real conservation concerns. Greenpeace, the World Wildlife Fund, and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature do not protest the fur industry because they do not consider it an environmental problem.

And anti-fur protesters are not really driven by animal-welfare concerns either. Animal-welfare groups (like the CAHT) that accepted the responsible use of animals but worked to improve the humaneness of trapping, have been superseded by media-savvy “animal rights” groups, like PETA. And while PETA distributes videos that it claims show animal-welfare abuses – and it will always be possible to find a bad apple somewhere – its publicly-stated objective is the elimination of any use of animals, even for food or vital medical research.

But when 95% of the population still eat meat and wear leather, it is disingenuous to claim that it is immoral to use fur that is produced responsibly and sustainably.

So the question remains: Is there still any justification for anti-fur protesters doing what they do? Is protesting against fur now just a way to attack "the establishment", or a smokescreen for promoting a radical “animal-rights” agenda? Or perhaps they have simply lost their way.

As American philosopher George Santayana said so succinctly, “Fanaticism consists of redoubling your effort when you have forgotten your aim.”

One of the most talked-about fur stories last month was the Gucci news that the brand would be dropping fur….

Read More

One of the most talked-about fur stories last month was the Gucci news that the brand would be dropping fur. It was surprising because Gucci has had great success selling fur (remember its kangaroo fur loafers?), but the fur industry has shrugged it off as sales are currently "strong and robust". Still, people are perplexed at the key reason Gucci gave for its decision: "sustainability". In Gucci's alternative universe, fake fur made from petroleum that pollutes the environment and doesn't biodegrade is more "sustainable" than the renewable, biodegradable resource that is real fur.

Here are some of the articles covering the perplexing Gucci news: the International Fur Federation asks why Gucci wants to choke the world with plastic, the Globe and Mail looked into the potential impact on Canadian trappers, and Truth About Fur dissected Gucci's "bizarre" interpretation of sustainability.

And while Gucci claims that millennials, who account for almost half its market, are against fur, this Business of Fashion article (above) talks about how this generation may actually be the one to boost the fur trade. If you want to delve into this further, Truth About Fur has a new blog post adding clarity to the relationship between fashion and the fur trade.

Just as illogical as Gucci's reason for dropping fur has been activists' campaigns against the growing number of restaurants serving seal meat. Their latest target is the indigenous restaurant Kukum Kitchen in Toronto (above). The people of Toronto like eating meat as much as anyone, and no one bats an eyelid at steakhouses or burger joints. But put seal on the menu, and the activists go into meltdown.

Or maybe it's just that general anti-meat protests are hard to take seriously, like this one of PETAphiles dressing up like scary clowns.

Meanwhile there's been the usual steady flow of news articles discrediting activist campaigns, like this one talking about PETA's kill rates, and this one debunking the idea that sheep can live without being sheared. If you have a business that is at risk of getting targeted by activists, check out Truth About Fur's guide to dealing with protesters, in person and on-line.

In the world of trapping and wild fur, a big Canadian story is the Royal Canadian Mounted Police's demand for 4,470 muskrat hats (below). Alan Herscovici, part of our team here at Truth About Fur, discussed the issues surrounding this story on the radio.

Wild animals are causing problems in several areas. Coyotes in the Yakima Valley need to be controlled, as do the deer on Staten Island. (Surprise, surprise, the deer vasectomy program didn't work.) Rather than spend money trying to sterilise these animals or find other strange ways to control the populations, we like the idea of starting a state-controlled company that sells the fur from pest and nuisance animals.

Interested in getting involved in conservation? Let's end this month's roundup with this great article on how we can all get involved in protecting our environment, and some nice animals on camera. Our favourite live cam right now is the the bison cam, which is following a herd of bison in Saskatchewan.

The fur retailing season is beginning, and with it we can expect the usual flurry of fur protests. Despite decades…

Read More

The fur retailing season is beginning, and with it we can expect the usual flurry of fur protests. Despite decades of anti-fur campaigning, activists have generally failed in their efforts to push designers and consumers away from using and wearing nature’s most beautiful clothing material. Fur has probably never been featured in so many top designer runway collections, and fur has certainly never been used in a wider variety of products, from apparel to accessories to home furnishings.

But animal rights activists are not very interested in opinions that differ from their own, so the fur protests continue.

Sometimes, consumers are harassed and retailers are warned that their stores will be targets until they stop selling fur. (Can you spell Protection Racket?) A favourite new tactic is the store invasion (often called Direct Action Everywhere or DxE) where activists enter a shop, individually, posing as consumers, and then pull out posters and begin chanting slogans in unison. One or more protesters film the “action”, taunting shop owners and security staff who dare not push them towards the exit for fear of being slapped with assault charges. Another nasty new trick is to flood a retailer’s Facebook page with negative comments and reviews.

Following are some ways to protect your retail business from animal rights protests.

While fur protests can happen any time – especially during the fur season – the next big activist target date is “Fur Free Friday” (the activist response to “Black Friday”), which falls on November 24 this year. Google "Fur Free Friday 2017” to see if your town is listed. Or monitor the national Facebook page.

There are many ways to find out about protests that may be planned for your store. Animal rights groups are often headquartered on university or college campuses, and they find many of their foot soldiers there. So monitor university bulletin boards. It's even better if someone you know can join the local animal-rights group. Or simply keep an eye on the Facebook page of your local animal-rights group.

Not least important, your national fur trade association can provide a timely heads-up when trouble is brewing, or advice and assistance if your store becomes a target. Be sure you are a paid-up member of the Fur Information Council of America (323.782.1700; [email protected]), or the Fur Council of Canada (514-844-1945; [email protected]). They need your support so they can be there to support you!

It is always best to build your relationship with local police before you need their help. It can be as simple as calling your local precinct and asking for a meeting with a commanding officer. Or speak with officers who patrol your street. Explain your concern that stores selling fur are often targets for protests or vandalism. Getting to know your local police can play big dividends: they can often warn you of up-coming protests, or keep an eye on your store at night, especially in the period before and after fur protests, a time when vandalism often occurs.

Not least important, police can be present during demos, to tone down rowdy demonstrators and ensure that consumers can access your store without being harassed. While police cannot “take sides”, they do have a mandate to keep the peace and prevent harassment or confrontation, which allows them to keep protesters a certain distance from your door. How they interpret this mandate often depends on what sort of relationship you have developed beforehand.

Remember always to file a police report about any harassment, threats, graffiti or other vandalism, no matter how minor. Take photos before scraping away graffiti from store windows or walls. And keep any threatening phone messages. Such incidents often precede more significant attacks. And these reports allow police to see patterns of radical activism developing, or to make a case with their commanding officers for devoting scarce resources to protecting your store.

You should also build bridges with your local business group or Chamber of Commerce, and with local politicians. Their support can help to ensure that the police will be there when you need them.

Most fur stores have good security systems to prevent break-ins and theft – insurance companies require them – but be sure you have security cameras and that they are functioning! Cameras surveying the inside of the store can help to identify protesters who enter your premises. Cameras facing the sidewalk can discourage vandalism.

One particularly nasty activist weapon is Butyric acid, a carboxylic acid that has an extremely powerful and unpleasant vomit-like odour. When sprayed under the doors of a store, at night, fur coats can be effectively ruined, as the smell is nearly impossible to remove. The best solution is prevention: ensure that there Is no way to spray anything under your doors or through keyholes or mail slots!

Plan and discuss the procedures you will employ if there is a protest at your store. As a general policy, do not engage or argue with protesters; confrontation will only encourage them and could make the protest more "newsworthy" if any media are present. Never touch or push protesters.

Some retailers have rented large cube vans to park in front of their stores, blocking the protesters from the view of passing cars or pedestrians on the opposite sidewalk.

If you know in advance about a protest, consider hiring professional security: they have the knowledge and experience to handle protesters lawfully and effectively.

If you are subjected to repeated or abusive fur protests, you should consult a lawyer: there is a considerable body of labour law relating to the legal limits of picketing.

It is rare that protesters try to enter stand-alone stores (DxE invasions usually target shops in malls), but if they do, ask them to leave, and call the police. Do not try to expel protesters physically; it is very likely that you are being filmed, and any physical contact could result in criminal charges.

It can be useful to have someone photograph the fur protesters, for identification if needed, and to let them know they are being watched. But check first to ensure that this is legal in your town. And remember rule number one: you do not want to escalate tensions or provoke violence. It is usually better to suffer through the occasional fur protest quietly, rather than make yourself a target for more protests.

For those who would like to respond more actively, the Retail Fur Council of Canada has produced a new tool for retailers to use if they are subjected to a DxE store invasion. Click on the posters below to download, then print them out and hold them up behind chanting protesters or in front of their cameras, or display them in store windows during fur protests. Messages include: “Say NO to extremists” and “Defend freedom of choice!” Such tools should be used with caution, though; you do not want to escalate tensions or make yourself more of a target.

Media now usually ignore fur protests, especially in larger cities. If journalists do ask you to comment, it is usually best to refer them to your national association (FICA or the FCC). Your association professionals are trained and better prepared to speak with the media ... and they have no street-level store windows to break.

If you do want to say something, keep it simple and positive, and then suggest that the journalist contact your national association for more information.

Here are some examples of the type of media statement you can make:

Several North American retailers have recently been hit with cyber-attacks where their Facebook pages are flooded with negative comments and ratings.

If this happens, here are some things you can do:

Finally, remember: It is always best to be prepared, but most fur protests are brief and relatively harmless. The most important thing is to remain calm and not be suckered into escalating the tension. If you learn that you will be targeted by a fur protest, contact your national association – they have the experience to help you get through these frustrating episodes.

Do you have any other ideas or experiences you would like to share? We would love to hear from you!

Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri puzzled many when he recently announced that the prestigious design label would go “fur-free” in 2018….

Read More

Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri puzzled many when he recently announced that the prestigious design label would go "fur-free" in 2018. The confusion wasn’t about the decision itself – fashion companies change directions all the time – but about Bizzarri’s claim that a fur-free Gucci was meant to demonstrate "our absolute commitment to making sustainability an intrinsic part of our business."

Mr. Bizzarri’s comments are certainly bizarre, and not only because Gucci was founded and is still known as a leather designer.

His comments are bizarre because, whatever your personal opinions about the ethics of using animals, there is no debate about the fact that the modern fur trade is an excellent example of environmental sustainability.

Perhaps someone should explain to this social-responsibility-climbing CEO what environmental sustainability really means.

Following is a short primer on sustainability and fur.

SEE ALSO: Sustainabiity: Why is Gucci so confused?

The concept of sustainable development was launched by the Brundtland Report, from the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), published in book form as Our Common Future, in 1987. As quoted on the corporate responsibility and sustainability page of Gucci’s own website, this landmark document proposed that our environmental challenge is to meet "the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

In layman’s terms this means living on the “interest” that nature provides, without depleting our environmental “capital”, i.e., the air, water, and natural ecosystems that we depend upon for our survival. So, whenever possible, we should use renewable resources (plants, animals) rather than non-renewable resources (petroleum-based synthetics). And we should use these renewable resources sustainably, i.e., no faster than nature can replenish the supply.

The sustainable use of renewable natural resources is based on the fact that most species of plants and animals produce more young than their habitat can support to maturity. The ones that don’t make it feed others. And we are part of this natural system. We too can use part of this natural “surplus” for our food, clothing, shelter and other needs.

Let’s see how fur measures up to these sustainability requirements. There are two main types of fur used today: wild-sourced and farm-raised. They have somewhat different implications for sustainability, so we will consider them separately.

The modern wild-fur trade is an environmental success story. All the fur we use today comes from abundant species, never from endangered species.

Thanks to national and international regulations, fur is an excellent example of the responsible and sustainable use of renewable natural resources.

To ensure that we use only part of the surplus that nature produces (“sustainability”), trapping is strictly regulated in North America by state, provincial and territorial wildlife biologists. Thanks to these regulations, the most important North American furbearers (beaver, muskrat, coyote, fox, raccoon) are as abundant today as they have ever been, or even more abundant. In fact, furbearer populations would have to be controlled in many regions even if we did not use the fur, to prevent the spread of disease or to protect livestock, property, other species or natural habitat.

SEE ALSO: Abundant Furbearers: An Environmental Success Story

And while not strictly a sustainability issue, it is also reassuring to know that North American trappers respect animal welfare. Modern trapping methods have been refined by more than 30 years of scientific research and must comply with the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (in Canada) and Best Practices (in the US).

Wild furs are, in fact, the ultimate free-range, organic and locally sourced clothing material. By contrast, most synthetic materials are made from petroleum, a non-renewable resource.

Not least important: when you buy wild fur you are providing income to First Nations and other people living in rural and remote regions where alternative employment can be hard to find. Helping people remain on the land – where they can monitor industrial activity and sound the alarm when nature is threatened – is also an important sustainability objective.

Globally, most fur is now produced on farms, and fur farms also contribute to environmental sustainability in several important ways.

Mink and fox are the most commonly farmed furbearers. They are carnivores, and are fed left-overs from our own food-production – e.g., the parts of cows, chickens, fish and other food animals that we don’t eat.

Farmed fur animals recycle food wastes into a beautiful, long-lasting and ultimately biodegradable clothing material, while their manure, carcasses and soiled straw bedding are used to produce bio-diesel and organic fertilizers, completing the nutrient cycle.

Fur animals are raised on small, family-run farms. And fur farms can thrive in regions where the soil is too poor or the climate too harsh for most other agriculture.

And, again, while not strictly a sustainability issue, it is reassuring to know that fur farmers provide their animals with excellent nutrition and care. Animal welfare is assured by legislation and various codes of practice, but, above all, because excellent nutrition and care are essential to produce high-quality fur.

As even this brief summary shows, Gucci’s new fur-free policy completely contradicts its CEO’s claims about "our absolute commitment to making sustainability an intrinsic part of our business."

Bizzarri also justified Gucci’s new policy by claiming that fur is “not modern,” a serious charge in the fashion world. But what could be more modern than using materials that are produced responsibly and sustainably, like fur?

Fur-free Gucci smacks of opportunism and hypocrisy because, as mentioned, Gucci has always been known for its leather products. Someone should tell it that leather is produced by scraping the fur from an animal hide.

Some argue that leather is a by-product of animals raised primarily for food. But some fur animals are also eaten, including various types of farmed sheep and rabbits. Beaver, muskrat and other wild furbearers also provide food for aboriginal and other trappers and their families.

Furthermore, not all leather comes from food animals – notably the python and other exotic leathers used extensively by Gucci. In fact, Gucci’s parent group, Kering, recently bought its own python farm in Thailand to ensure good welfare conditions for the reptiles its members use. If Gucci was concerned about the welfare of fur animals, instead of dropping this beautiful and environmentally sustainable material, surely it would have done better to inspect the fur farms that supply it, or learn about how wild fur production is regulated.

Perhaps the good news in this story is that Gucci's bizarre decision about fur provides an opportunity to begin a more serious public discussion about the real meaning of sustainable living. And companies like Gucci can play an important role in this discussion. But first, it would do well to do its research and review its ill-conceived position on fur.

If you want to tell Gucci what you think of its new fur-free policy, you can contact it here (options vary depending on region, just pick one). Include the URL of this blog post, and recommend viewing of Furbearing Animals: A Renewable Natural Resource, by the Fur Council of Canada.

Or you can email Gucci directly at: [email protected]

Or telephone: 1-877-482-2499.

SEE ALSO:

Does Gucci Really Want to Choke the World with Plastic Fur? By Mark Oaten, CEO, International Fur Federation

Gucci: Ethically Minded or Sadly Mistaken? Things that Make You Go Hmmm. FurInsider.com

Even those of us who think dressing up means jeans and a clean T-shirt have an opinion about “high fashion”….

Read More

Even those of us who think dressing up means jeans and a clean T-shirt have an opinion about "high fashion". Skinny models in bizarre outfits … we’ve all seen them in old copies of Vogue begrudgingly read in the dentist’s waiting room. And since high fashion loves fur, it can also influence our opinion of fur fashion in general, and not always in a positive way.

That’s right. High fashion, with all its excesses, is a double-edged sword for the fur trade. While those who understand it value its promotion of fur, the jeans-and-T-shirt crowd can be left thinking fur fashion is a lot of frivolous nonsense. Or worse, a waste of animal life.

So for all the fashion heathens among us, let’s learn more about how high fashion works and why it is so important to the fur trade. To this end, I interviewed our resident fashion insider, Alice, who has years of experience working in the luxury fashion sector.

Simon: The public’s view of high fashion, or haute couture, can be rather negative. Designers with exotic names making outlandish outfits for a handful of wealthy clients make it seem elitist and self-indulgent.

Alice: First let’s get our terms straight. Haute couture and high fashion are not the same and have different objectives. Haute couture describes a very small niche of the luxury fashion world, hand-making one-off pieces that only royalty and oil sheiks can afford. High fashion is a loose term for the collections of luxury designer brands that are for sale to the general public and influence trends in mass-market fashion.

Simon: Whatever they’re called, some of their pieces are so weird, no normal person could carry them off, so why bother?

Alice: If pieces look unwearable, it’s probably because they’re not meant to be worn. But they have a definite purpose; they represent the big ideas of a collection. These ideas are then tapered down into more normal items for the stores of the designer brands. Fast-fashion and mass-market brands then make them even more commercial and sell them on the high street.

So while a designer-brand show may feature an insane, brightly coloured fur coat with feathers and all kinds of things sticking out of it, its stores may not even have that coat. It might have a production run in single digits, with less volume and no feathers. Then a high-street store will make a bolero jacket with the same colours but fake fur. It gets massively tapered down.

And sometimes catwalk pieces aren’t for sale at all. These are called “press pieces”. Again, they represent the big ideas, but they look super spectacular because their purpose is to make the pages of magazines. So a stylist might look at a collection of sheared mink jackets decorated with beaded flowers, and then ask the atelier to make a mink bikini top and matching headband, covered in beaded flowers, and pair it all with a long skirt with a train. No one would ever go to the beach dressed like that, but it makes an impact on the catwalk.

Simon: When I need a new pair of cargo shorts, I don’t check Vogue first. I just head to the store and buy the first pair that fits. Are buyers of fur fashion so different?

Alice: Yes. Fur fashion is part of the luxury sector, and buyers of any luxury goods, not just fur, behave differently from buyers of $10 cargo shorts.

Most people with $10,000 and more to spend on a fur coat don’t just walk into a store and pick one they like. A seed has already been planted in their mind of what they want, and designer brands plant these seeds by having their clothes on the catwalk and being worn by celebrities and other influencers.

And when that happens, it’s very important for furriers and fur manufacturers to be on trend. At the last New York Fashion Week, rapper and style icon Nicki Minaj got a lot of media coverage in a $19,000 Oscar de la Renta fox coat. It’s likely that this style of coat is going to be popular at retail now, and the furriers may have even placed rush orders to get similar coats in stock. “Trickle down” would also see cheaper, less-flashy versions in fast-fashion outlets, maybe even made of fake fur.

Simon: Trickle down?

Alice: Yes, trickle down theory is when a designer brand sets a trend, and others follow suit with more affordable versions. There’s also “trickle up”, like if designer brands are inspired by street style or subcultures, like punk or hip hop. But for luxury goods like fur, trickle down is key.

Simon: So how far down does it trickle? Surely Canada Goose, known for its functional coyote-lined parkas, doesn’t care what designer brands are doing.

Alice: It certainly does. Canada Goose is known as a performance brand, but it’s already collaborated with French designer brand Vêtements, and I expect it to be influenced more and more by high fashion in the next few years. It gives Canada Goose credibility – a “cool factor” – to be associated with a designer brand, rather than just being known for functional parkas. And it will sell more of the regular coats just because it happens to have a couple of fashion-forward ones available.

A better example of these collaborations is H&M. While it’s known for its fast-fashion, it’s had huge success collaborating with a string of designer brands and celebrities.

SEE ALSO: 5 Reasons Why PETA Won't Make Me Ditch My Canada Goose

Simon: Critics of fur fashion say it’s “frivolous”, and of course they’re not referring to raccoon hats in Winnipeg in winter. They say that when fur is used for purposes other than keeping the wearer warm, the taking of animal lives cannot be justified. A real need must be met, and fur sandals don’t meet the standard. Even some trappers feel this way. They lament that they work hard all winter so someone can wear a pink fur bikini with pom-poms on.

Alice: That sounds like a great argument; no one wants to see animals being killed for no good reason. But where the fur trade’s concerned, it doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

Furbearers are farmed and trapped above all to make cold-weather clothing, and if this clothing also happens to be fashionable, it does not lessen the fact that its primary purpose is to keep people warm. As for accessories, you must remember that animals are not killed for the purpose of making these. The vast majority of fur pelts, and certainly of prime pelts, are made into coats, and accessories are made from whatever's left. This includes scraps, parts like tails that are normally only used for trim, and the good parts of damaged or low-quality pelts.

A friend of mine once won a set of mink golf club covers in a raffle and, curious to know how much they were worth, asked around. It turned out they were very affordable because they were made from the pelts of farmed mink that died naturally before their fur had fully grown. He was a little disappointed, but also comforted to know that mink were not being raised for the express purpose of keeping golf clubs “warm”!

So accessories are very much secondary products to cold-weather clothing, and should actually be seen in a positive light because they demonstrate the industry’s dislike of waste.

SEE ALSO: Why Fur Is the Ethical Fashion Choice

Simon: Still, some stuff is perceived badly by some people, especially the silly stuff like furry bag charms or covers for iPhones. The fur trade seems to be courting criticism for appearing insensitive to the fact that animals have died, while producing items that don’t even help their core business.

Alice: What you call “silly” stuff, marketers call “fun” stuff, and they exist in all areas of retailing. And you’re mistaken if you think they don’t help the core business. It’s a proven marketing strategy that by offering fun items at low prices – entry-level items – more people will end up buying the high-end product you really want to sell. So if a girl buys a furry key-ring bauble and ear rings and all her friends think they’re awesome, then her next step might be to buy a fur scarf. And when she grows up, her attraction to fur may translate into a full-length coat.

Small, affordable items also generate exposure to friends of people who buy them, and open up debate about your product. Those iPhone covers, for example, have had an amazing amount of media coverage, all positive.

So if turning a small percentage of pelts into cute accessories opens up the dialogue about fur, makes it more accessible, and gets more people to wear fur, it makes perfect business sense to do it.

And as I’ve already said, animals are not killed for the purpose of making accessories. If anything could be said to show disrespect for animal lives it would be throwing the fur scraps away. Instead, they are used to create fun items that give people pleasure. There’s nothing wrong with that.

Simon: So to sum up, how important is high fashion to the fur trade?

Alice: Extremely important. While fur is on the catwalks, it continues to be a fashion item and is in demand in the fashion market. Without the fashion component, we will see many more "practical" fur pieces, such as parkas and more simple coats whose sole purpose is warmth, but less of the stylish pieces.

It’s vital that fur fashion appears in the media and that is achieved by putting it on the catwalk and on the backs of celebrities. No one is better at doing this than designer brands, and they also have the money to pay for advertising.

But remember that high fashion influences every sector of the fashion industry, not just the luxury sector. Any company involved in designing, producing or marketing clothing is constantly alert to what direction the market is taking. They follow current trends but also hope to predict future trends, and for this they look to designer brands, fashion media and celebrities.

So as consumers, we might think that high fashion is irrelevant to us and that we make independent decisions about what to wear. But that’s rarely the case. We are all subject to being influenced, and though we may not know it, high fashion influences what every one of us wears.

Let’s start this month’s roundup on a serious note – polluted water is serious, right? – and talk about synthetic…

Read More

Let's start this month's roundup on a serious note – polluted water is serious, right? – and talk about synthetic fibres. Activists constantly promote fake fur as an alternative to real fur, but it is not a viable alternative. It doesn't keep you as warm, it doesn't feel as good, and it doesn't last as long. But worst of all, it is made from petroleum by-products, and synthetic fabrics are responsible for microplastic contamination in our food, in our water, and in the air. We are literally breathing in plastic pollution from synthetic clothing, and activists are still wasting their time protesting fur.

Speaking of activists doing stupid things, these Buddhist monks were fined for releasing lobsters into the ocean, because the creatures are now threatening the entire ecosystem. (They were not native to the area.) So now we are seeing not only microplastics in the polluted water, but destructive lobsters too.

This group stole a bunch of chickens from a small family farm – let's hope they are jailed. Other animal rights shenanigans from last month include Pamela Anderson's email to Canada Goose staff asking them to stop using fur (they've declined to do so), and these fashion week protests where activists were spitting on people (and the victims weren't even wearing fur).

PETA has turned its attention to attacking the wool industry (pictured), but as this writer explains, shearing sheep is absolutely necessary and the activists don't know what they are talking about. It's nice to see the Huffington Post taking a break from its animal rights coverage to publish a piece about how the movement is hurting people to protect animals. We're no stranger to fighting off the AR's, and our senior researcher wrote a piece recently about his years of fighting the anti-fur activists.

While California is trying to ban all commercial trapping (a bad idea for a state that sees frequent coyote attacks on pets), we've published a piece on how animals that are trapped commercially have very healthy populations – proof that regulated trapping does not negatively affect animal numbers. That said, we do think that trapping is best done out in nature, not from your sofa.

We were happy to hear that seal meat is back on the menu in Canada, this time in Montreal, and that one of fashion week's most talked-about celebrity outfits featured a fur coat.

Speaking of fur coats, these Canadian mink farmers are organising a winter coat drive – adding to the mountain of evidence we have that fur farmers aren't the evil people activists make them out to be. But then activists don't talk to farmers or visit farms, and as this writer explains, visiting a fur farm can only change your perception of fur farming for the better.

Let's end this roundup with a few of the other surprising stories we read last month (though nothing is as shocking as the microplastic-polluted water and air story we mentioned above):

Someone is trying to grow leather using biotechnology (and no animals).

Someone else is trying to make animal-free meat (pictured).

Hunters and vegans have a few things in common. (Trust us, this is a good read.)

And lastly, the least surprising story of the month: a feature on why people gave up veganism. (Hint: it's because they didn't feel well on a plant-based diet.)

It has been some 35 years since I began promoting the ethical credentials of the fur trade and denouncing the…

Read More

It has been some 35 years since I began promoting the ethical credentials of the fur trade and denouncing the fallacies of animal-rights extremism. As a pro-fur warrior, I have had many odd and interesting encounters, some of which you may find amusing. Following are a few memorable moments, in no particular order.

After the publication of my book Second Nature: The Animal-Rights Controversy, in the mid-1980s, I was often asked to address groups of livestock producers and others who worked with animals, to explain the new challenges posed by the emerging animal-rights movement. To help my audiences understand the animal-rights philosophy, I liked to throw out a challenge: Why, I asked, do we think it’s “OK” to kill and eat a cow, for example, if we don’t think it’s acceptable to kill Charlie, sitting there in the first row, even if we sneak up on him while he’s sleeping so he doesn’t feel any stress or pain?

The question invariably produced a chuckle, and it got them thinking. But it didn’t faze one old cowboy who had been tasked with thanking me for my presentation to a group of Western Canadian cattlemen. “By the way: the reason it’s OK to eat a cow but not Charlie,” he said, turning to look at me with a sly grin, “is because the cow has its eyes on the sides of its head.” What he meant, of course, was that predators – including tigers, owls ... and humans – have eyes in the centre of our faces, to provide the bifocal vision needed to accurately evaluate pouncing distances. Prey animals generally sacrifice such precision for a wide-angle view of approaching danger. I was supposed to be the communicator, but that weather-beaten rancher summed up a central dilemma of the animal-rights debate in just a few words.*

Some of my encounters have sounded a more touching note. I will never forget the young Inuit woman in tears after I brought her to an animal-rights lecture, she was so hurt by the way her people’s hunting traditions were denigrated. A dairy farmer’s daughter also cried as she told me how it felt to be labelled “cruel” by friends at school because of her father’s work: “My father who trudges out to the barn yet one more time before going to bed, even in the most bitter cold, to be sure ‘his girls’ are comfortable for the night!”

And then there was the Newfoundland hunter who thanked me for my writing because “it’s good to know that someone out there understands who we really are, our way of life.” And the Cree trapper who read Second Nature, footnotes and all, through a long winter season alone on his northern trap-line.

Each of these encounters, and many more like them, has rekindled and reinforced my determination to expose the cruel impact of misguided animal-rights campaigning.

Other incidents had a more absurdist twist. Like the time I was invited for a media tour in England. Because of concerns about Animal Liberation Front violence – particularly nasty in Britain at the time – my hosts had taken security precautions. My name was registered at the chic West Kensington hotel only as “Incognito”. I didn’t think anything of it until that night when I phoned the front desk for a morning wake-up call. The receptionist confirmed the hour I had requested and then asked, “Will there be anything else, Mr. Incognito?” I assumed she was being ironic, until she added, “By the way, is your name Italian?”

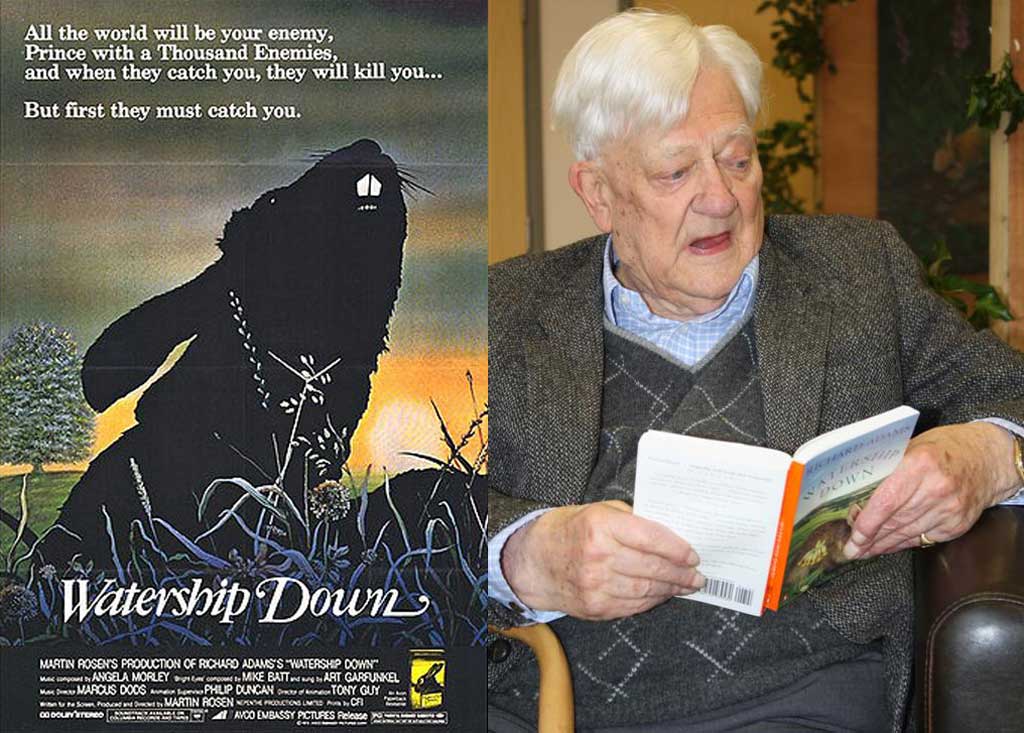

Equally absurd, although certainly more disturbing, was my encounter with Richard Adams, of Watership Down fame. When not writing about the secret life of rabbits, Adams was an animal activist who travelled to Canada to protest the seal hunt in 1977, and enjoyed a brief and turbulent stint as president of the RSPCA. When I met him in the late 1980s, Adams was campaigning against the fur trade in the United States, and I was asked to debate him on Boston television. He refused to shake my hand when we were introduced before the broadcast ("I wouldn’t shake hands with Hitler," he explained), but I stole his thunder – and precious minutes of live television time – by sticking my hand into a soft-catch fox trap “on camera” while explaining why his claims about cruel trapping were misinformed and outdated.

The best was yet to come. After the TV debate, we were invited for an in-depth interview by a Boston Globe journalist. She offered Adams the opening salvo, but he ignored her as he busily perused a sheaf of notes. After I explained a few facts about fur, she turned to Adams again. Still not a word. So I was able to explain a bit more. And then more. Until, suddenly, as the journalist reported in the next day’s paper, Mr. Adams gathered up his papers, stood up without a word, and left the building.

I saw Richard Adams one more time, a few days later, at a New York television studio where we were scheduled to debate again. I was waiting in the Green Room when Adams walked in and informed the producer that he would not appear on the program if I was there too. The producer asked him why? “Because he’s insane,” Adams replied. “We have lots of insane people on New York television,” the producer assured him. Adams left. He had made a calculated decision, I realized: he was scheduled to speak at dozens of US colleges and would be interviewed by many journalists over the next ten days – alone. Why share the limelight with someone who actually knew something about trapping and fur farming?

Postscript: A few years later, a rabbit cull was organized on the Isle of Man, a tax haven where Richard Adams had fled to protect the fortune his books had generated. An enterprising journalist decided that it would be interesting to ask the famous rabbit author for his thoughts about the cull. “You have to remember that my book is fiction,” said Mr. Adams. “In real life, rabbits are a pest.” Or as Mr. Adams told another journalist: “If I saw a rabbit in my garden, I’d shoot it.”

*NOTE: Some scientists now believe that human bifocal vision developed when our ancestors took to the trees, improving our ability to leap from one branch to another. According to this hypothesis, bifocal vision in this case did not make us better predators, it made us less-accessible prey! Subsequently, of course, it also made us much more effective predators.

***

The author is an internationally recognized defender of the fur trade. Raised in a fur-manufacturing family, he is the author of Second Nature: The Animal-Rights Controversy, the first serious critique of the animal-rights movement from an environmental and social justice perspective. Herscovici served for 20 years as Executive Vice-President of the Fur Council of Canada and is the creator of Furisgreen.com. He is now the senior researcher/writer of TruthAboutFur.com.

People I speak with are often astounded to learn that all the furs we use today are abundant. “We never…

Read More

People I speak with are often astounded to learn that all the furs we use today are abundant. “We never use furs from endangered species and we are not depleting wildlife populations,” I explain. “In fact, the most commonly used North American furbearers are now as abundant as, or more abundant than, they have ever been.”

“How can this be?” they ask. After 400 years of commercial fur-trading, with so much urban and industrial development, how can fur-bearing animals be as plentiful as before Europeans arrived on this continent?

There are two main reasons why North American furbearers are so abundant, both of which are surprising to many. The first reason is that modern wildlife-management regulations have been remarkably successful in ensuring the responsible and sustainable use of fur-bearing animals. The second is that human activity is not always bad for wildlife.

Because neither of these facts is well known or understood, let’s take a closer look.

The hunting or trapping of wild fur-bearing animals in Canada and the United States is strictly regulated by the state and provincial (or territorial) governments. Government wildlife biologists regulate the impact of hunting or trapping in a number of ways, including the setting of “open seasons” (and sometimes harvesting quotas) for different regions and species. Open seasons are timed to avoid the periods when animals are reproducing or caring for their young, and are designed to target the natural “surplus”, animals that exceed the “carrying capacity” of their habitat. Hunting and trapping seasons can be lengthened, shortened or closed completely, if necessary, to maintain a balance between wildlife populations and available habitat.

Trappers are licensed and must complete training programs before receiving their permits. These programs teach conservation principles, the proper way to use new humane trapping devices and to ensure that only the targeted species are captured, pelt-handling techniques (to avoid waste), and survival skills.

Since the 1950s, furbearer populations have been restored across North America

Trapping was not always so well managed. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, populations of beaver and other abundant furbearers were depleted by over-harvesting in some regions. With the introduction of modern wildlife management policies and regulations, especially since the 1950s, furbearer populations have been restored across North America.

It is easy to understand how government regulations can prevent over-harvesting. What is less well-known is that regulated trapping can actually help to stabilize the populations of some wildlife species. Beaver populations, for example, are naturally subject to extreme “boom-and-bust” cycles. If adequate supplies of their preferred food (e.g., willow and ash trees) are available, beaver populations can rapidly increase until all available vegetation is depleted (“eat-out”). Fighting for scarce remaining food, disease and starvation will then take their toll and beaver populations will “crash”; there may be no beavers at all in this area for many years, until suitable vegetation is restored.

Regulated trapping can smooth out these boom-and-bust cycles, keeping beaver populations in balance with available food supplies. The result is more stable and healthy beaver populations than would occur naturally.

Even less well-known than the stabilizing effect trapping can have on wildlife populations is the fact that human presence can actually benefit some animals. While the expansion of cities, farms and industry can certainly disrupt natural habitat, for some furbearers it has allowed populations to increase.

A case in point is the raccoon. Our cornfields and urban garbage have allowed raccoons to expand their population and range, including northward into much of southern Canada where they were not present before.

Raccoons, foxes and coyotes are now more abundant across North America than they have ever been

Red foxes and coyotes have also benefited from humans, in two ways. Mature temperate and boreal forests do not support an abundance of wildlife, but when farmers clear parts for pastureland, habitat is created for mice and other small rodents on which foxes and coyotes feed. Foxes and coyotes have also benefited from their ability to adapt to living in close proximity to people, while wolves – apex predators and their competitors for food – have been pushed away from human settlements.

As a result, raccoons, foxes and coyotes are now more abundant across North America than they have ever been.

Human activity can improve wildlife habitat in other surprising ways. Roads built through marshy regions – as are found across much of northern Canada – are protected with ditches that help to drain excess water from the land. Ash and willow can then grow, bringing beavers which, with their dams, create ponds that attract a wide range of other animals. This sort of habitat improvement, combined with modern wildlife management regulations, has restored abundant beaver populations across North America.

At a time when we are concerned about the depletion of many wild fish stocks and terrestrial species, the responsible and sustainable management of wild fur-bearing animals is a remarkable environmental success story. And that makes fur an excellent clothing choice for anyone concerned about protecting our natural environment for future generations.

***

FURTHER READING

Rise of the coyote: The new top dog. Nature magazine, May 16, 2012.

After 200 years, a beaver is back in New York City. New York Times, Feb. 23, 2007.

"... protection and re-introduction programs have re-established the American beaver throughout its historical range. It is now abundant." IUCN Red List.

"After a population explosion starting in the 1940s, the estimated number of raccoons in North America in the late 1980s was 15 to 20 times higher than in the 1930s, when raccoons were comparatively rare." Wikipedia, citing Raccoons: A natural history, by Samuel I. Zeveloff.

Game of Thrones costumes are dominating fashion media right now, so it’s a good way to start our round-up of…

Read More

Game of Thrones costumes are dominating fashion media right now, so it's a good way to start our round-up of fur news from August. Set against a backdrop of ice and snow, the medieval fantasy epic inevitably features lots of furs, but they aren't necessarily expensive pelts. In fact, some of the capes are made from Ikea rugs! That's clearly not the case, though, with this spectacular coat (pictured), made from a combination of real fur and fake.

If you aren't into wearing full-length coats or rugs, then how about accessories? We love these Wild and Woolly fur iPhone cases and are very excited to see that fur shoes are still making waves. In fact, one of the best-known fur brands, known for its spectacular fur accessories, is opening its first San Francisco store.

Animal rights activists have been busy (no rest for the wicked – literally). PETA launched an anti-hunting campaign that backfired on them, they are claiming cheese is a symbol of rape, and they had to apologize for stealing and killing a girl's pet dog. At a conference this summer, the activists discussed their change of tactics: go after companies instead of individuals, which unfortunately has had some success for them. But they aren't always able to get much traction outside of the digital world, as this article suggests.

We are frankly fed up with their hateful campaigns and their attack on our rights. They need to be called out for what they are: hate groups.

On the bright side, they sometimes prove to be their own worst enemy. A recent study showed that aggressive vegans make people want to eat more meat, and that one-third of vegetarians eat meat when they are drunk. It's time to spike their punch!

Speaking of bad smells ... the skunk population of Fox Valley, Illinois is exploding and low pelt prices are not helping. Concerned about the possibility of rabies, residents are raising a stink. And in nearby Macoupin County, there's the same problem but with raccoons. Louisiana is dealing with its own pest problem and is looking for trappers to help control the nutria population.

These stories truly highlight the role of the trapper in pest control, but what about conservation? A post on our blog asks whether trappers are conservation’s “black sheep” or unsung heroes.

Fur trade history stories continue to be in the media, following the celebration of Canada's 150th anniversary of Confederation in July. This boat is doing a 100-kilometre trip to re-trace the routes from the days of the Canadian fur trade, and the people of Southampton have been celebrating Métis history and its role in Canada's fur trade history. This trapper reminisces on his trapping days and how it was educational and profitable.

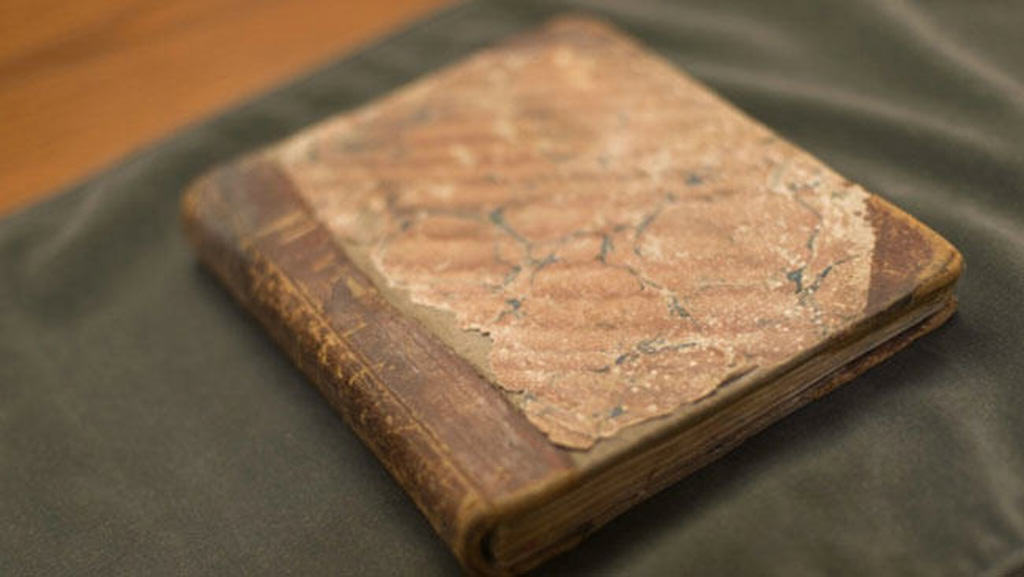

If you're a history buff then this 19th-century fur trade diary (pictured), recently acquired by the University of British Columbia, is going to be a fascinating read. If you're interested in historical fashion that's a bit more accurate than the Game of Thrones costumes, you'll wish you'd visited this "Fur Trade Fashions" show.

Let's end by dispelling a few myths for you.

The fur trade is criticized by activists for killing animals “just for their fur”, when in fact the list of…

Read More

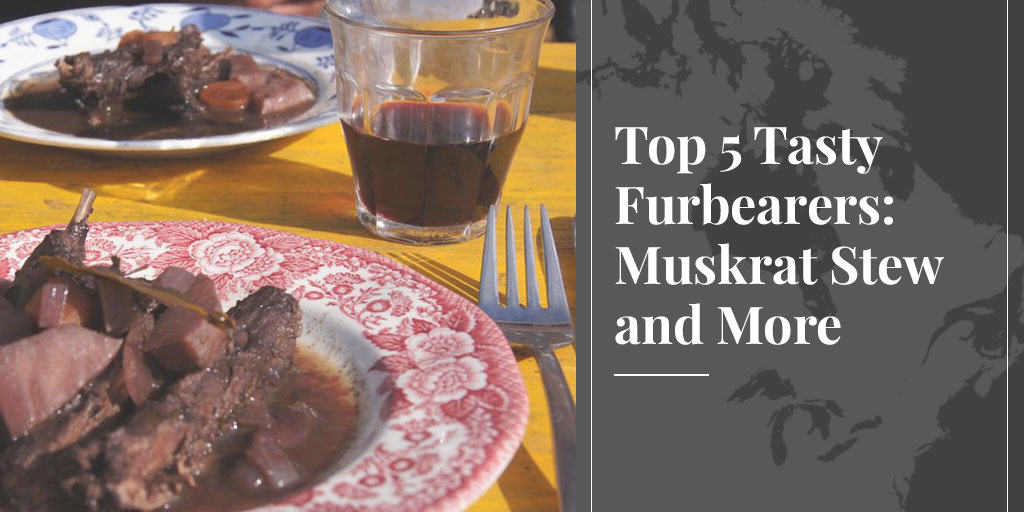

The fur trade is criticized by activists for killing animals "just for their fur", when in fact the list of by-products is long and diverse. Carcasses are made into fertilizer, bio-fuel, pet food and crab bait, while rendered fat is used in leather tanning and cosmetics. And don't forget (cue drum roll) muskrat stew!

City-dwellers find it hard to swallow that furbearers taste good, and in some cases they're right. Opossum, skunk and coyote will never make it onto a gourmet menu. But there's still plenty of fine dining to be had!

So without further ado, here’s our list of Top 5 Tasty Furbearers.

At number five in our countdown comes bear. We’d rank it higher because just one animal can feed a village, but laws governing the sale of wild meat mean you can't just walk into your local store and buy bear.

Eating bear has a long history in North America, and "roast bear was on the menu for more than a few state dinners during our nation's youth," writes Holly A. Heyser in The Atlantic. But beware. The saying goes, you are what you eat, and it's never truer than for "insanely variable" bear meat. "Eat a bear that had been dining on berries and manzanita and you are in for a feast. Eat a bear that had gorged on salmon and it'll taste like low tide on a hot day. Ew.”

But there's a bonus, no matter how your bear turns out. Save the fat because eggs and beans fried in bear fat – yum!

In fourth place comes squirrel. We like these critters because they're really dual purpose, providing fur and food for a lot of people. Nine percent of all furbearers trapped in Canada are squirrels and 5% in the US. Squirrel fur is not that valuable, but feeding a lot of hungry mouths gives them added value.

Old-Fashioned Squirrel Stew is said to be “downright delicious” and looks it too! Or get creative with these recipes for pot pie, fried squirrel, and baked squirrel.

Coming in at number three is muskrat, for two reasons. First, because muskrat stew tastes great. And second, because North Americans consume so many of them. Muskrat fur is not as wildly popular today as it once was, but it’s still the most trapped furbearer, accounting for 35% of animals taken in the US and 28% in Canada.

Just remember that muskrats are named for their musk glands. Fail to remove these properly and you're in for an “unpleasant dining experience”, but clean it right and cook it right and it’s “delicious”.

At number two comes succulent seal, and it might have come in first if it weren't for one sad fact: Americans are not allowed by law to enjoy this culinary delight.

What we really like about seal meat is that it’s not a “by-product” of harvesting fur, but a product in its own right. Seal meat has been an important source of protein for Canada’s Inuit since the dawn of time. It’s also important to the economies of all sealing communities, especially since the EU joined the US in banning almost all seal products.

With very little fat, seal meat is extremely healthy, and its mild, briny taste means it can be prepared in many ways – smoked, tartare, seared top loin, mixed with pork for a sausage flavour, and so much more. So it’s also growing in popularity with city-dwellers looking to combine healthy living with fine dining.

And at number one in our countdown comes ... beaver! Once a favorite of Mountain Men, it's still popular today and widely available. We also like that one large animal can feed a family. And provided you take great care in removing those smelly castor glands, it can pass for brisket. Here’s a recipe for beaver stew, and one for pot roast.

But the clincher for us in naming beaver our favorite furbearer feast is the tail. It's made almost entirely of fat, and is the part Mountain Men wanted most of all to keep them warm through the long winter nights. We must be honest, though; part of its appeal is that it's notoriously easy to mess up. Do it wrong, and you'll think you're eating Styrofoam, but cook it right and it will melt in your mouth like butter!

Bon appétit fur lovers!