Things Animal Rights Activists Say – Part 1

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeIf you’ve worked in the fur industry or been vocal about your love for fur, then you have probably suffered…

Read More

If you’ve worked in the fur industry or been vocal about your love for fur, then you have probably suffered…

Read More

If you’ve worked in the fur industry or been vocal about your love for fur, then you have probably suffered some verbal abuse from animal rights activists. Animal activists like to claim they hold the moral high-ground and that they are the compassionate ones. Well, let’s look at some of the things these models of compassion say ...

"I dont care about humans being exploited. animals arent in control of their destiny. period. i realise humans are massively destructive to everything. thats why i hate em.” [sic]

- animal rights activist (source)

If you hate humans so much, why don’t you go and live in the forest by yourself?

"We will demystify incarceration. Jail is not a problem. It presents an opportunity to recruit."

- animal rights activist (source)

We agree! Let them all go to jail please!

(more…)The morning started just like any other during my fall trapping season this past November. I fumbled about as I awoke…

Read More

The morning started just like any other during my fall trapping season this past November. I fumbled about as I awoke to the sound of my alarm clock just before sunrise. I didn’t really want to get up; I had spent several hours in the fur shed the night before, processing otter and beaver hides and, frankly, I felt as if I had just put my head on the pillow. So goes the life of the modern trapper.

The majority of trappers in the “lower 48” nowadays are part-time fur harvesters, holding down regular day jobs while juggling activities like fur trapping. We bare the same grit as the long-line mountain men of the northern wilderness, but return to civilization after running the trapline. If you work hard enough, chances are pretty good you could make a mortgage payment with the stack of fur pelts harvested at the end of the season. Some years, when the fur market is down, you’re lucky to recoup your cost for fuel and supplies. I harvest a modest and diverse collection of prime pelts each season, and rather than send to the overseas fur markets, I sell tanned finished pelts locally in the form of crafts, garments like mittens and hats, or as unaltered skins ready for locals to make their own natural garments out of. Most modern trappers aren’t in it solely for a few extra bucks – conservation, heritage, family-tradition, exercise, insight, an escape outside, take your pick; there’s millions of reasons why modern trapping is alive and well in North America. We’re not quite Hugh Glass material, but we sure aren’t “flatlanders” either!

With the alarm clock still buzzing, and before my conscious self could protest, I found myself already in yesterday’s pair of flannel-lined jeans, and in my truck. The drive down off the hill and into the valley is a ride I know all too well, especially during trapping season. I arrived at my first chunk of land on the trapline; a winding maze of hills, valleys, brush, and swampland carved into the side of a southern New Hampshire mountain range. I strapped on my hip-waders and slid my arms through the damp Alice pack filled with trapping supplies as I follow my bushwhacked trail through the dense Alder brush. I trekked into the still and dense forest as the sun began to break, putting a slight end to the constant hum of the pitch-black hillside.

The sights, the sounds, and the smells put my senses on high alert. What I see, touch, feel, and experience, you can’t acquire on a simple weekend hike through the woods on a walking trail. It’s something that can only be experienced when you fully immerse yourself into your natural environment and fulfill the role as a fixture of that environment, rather than a visitor. It’s real, raw, and organic, and it’s something only another trapper can fully understand. As I walked the same stretch of stream bank I’ve walked for the last thirty days, I stopped to take notice of a fresh mound of mud and stream debris piled high in a stumpy pile on the bank. It was clear these were fresh territorial markings from a beaver - markings that were not present during the previous day’s trek.

Suspicions are confirmed as I come upon my first trap lying on the river bottom, with a prime beaver lying motionless in the 330 Conibear trap’s strong and efficient grip. I take a moment with every creature I trap to reflect. I study the animal from top to bottom, noting any odd characteristics to its appearance. I give a brief "thanks" to the forest, reset the trap, and stash my gift from the woods on the river bank to be picked up on the return trip. Two beaver would be hauled out that morning and I would readily admit there are some days I get pretty tired of hauling 60 to 120 pounds of dead weight up the brushy hillside. The cycle repeats itself every morning before I head to my job back in civilization.

The day’s catch is left on the cool floor of my garage, as I get changed and suited up to start my workday. I return home in the evening to skin and process the furbearers I trapped that morning. There’s no "wait until the weekend" when it comes to trapping. Your catch must be handled quickly to keep up with the season’s demands. The animals are skinned and the hides are fleshed, stretched and dried. I remove any edible meat, useful bones, and glands from the remaining carcass. I take a moment to envision the usage for each pelt; which ones will make mittens, and which ones are better suited for blankets or hats. Some pelts may provide relief for a mortgage payment, and others may pay for fuel during the long Northeast winter.

This is the life of many trappers – cut from the same loins as the Alaskan and Canadian fur trappers of the uncharted lands, except our trade is carried out on the fringes of modern society and civilization. For many of us, the lifestyles of characters like Jeremiah Johnson and Hugh Glass are a prideful glimpse into a simpler time in America’s history. I consider myself fairly self-reliant by today’s standards. I’ll admit however, I’m far from the homesteading mountain men of the far north that so many of us envision. It’s the duality of being able to run a wilderness trap-line, brave the harshest of natural elements, and work a full-time job afterwards that I think makes the modern trapper such an interesting element in today’s overworked society.

The majority of my trap-line is carved along borderlines of modern metropolitan areas. The modern trapper utilizes culverts and freeway bridges to our advantage, stacking up catches that would make any 1800’s pioneer blush. Much like the furbearers we seek, we have adapted and learned to co-exist with modern society nipping at our heels. We stubbornly cling to traditions passed on from generation to generation. I find immense beauty in the fact that I can harvest my fair share of otter and fisher in the undisturbed wild mountains, and, in the next breath, head 25 minutes east and stack up a modest catch of muskrat and mink from the spillways behind the local strip-malls.

When I was younger, I scoffed at the idea of running an “urban trap-line”. I always felt wild critters could only be caught in wild places, well off the beaten path. Raccoons and opossums are synonymous with the urban setting, but in the early years, my naive thought process pictured most critters to be bound to the remote stretches of New Hampshire. For years I always sought the darkest, thickest hillsides I could find in my area. It wasn’t until I dove head-first into the world of Wildlife Damage Control that I realized just how close these creatures lived to the human populous; or should I say, how close humans live to them.

I’m often told trapping has no place in the modern world, and I need to “evolve”. Some say it’s antiquated, outdated and obsolete. I would argue that despite public perception, few people champion our wildlife and wild resources more than the modern fur trapper. Not only are we fully vested and immersed in our natural world, but we are also the first line of reporting and observation for all aspects of furbearer biology and general wildlife conservation. We are the first to feel and report dramatic population decline, disease, and environmental issues affecting furbearing species of wildlife that would be otherwise overlooked. For example, muskrat and weasels are not typically at the forefront of yearly headcounts by biologists, and until these animals start disappearing from the landscape, there wouldn’t be any checks or balances for their overall population health if it were not for the reporting and harvest by the modern trapper. Any unbiased furbearer biologist will tell you trapping plays an important role in the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation; this is fact.

Public perception has certainly taken its toll on the modern trapper. Somewhere down the line of American evolution, we began to set social norms for what was deemed "okay" for harvesting our nation’s natural resources. Killing for food, for instance, is generally socially tolerated, while taking an animal’s life for a beneficial garment is somehow deemed "selfish" or "greedy". At some point, we seemed to lose the bearings of our moral compass, shaming perceived “luxury items” like fur garments as “materialistic” while we wait in line for the latest and greatest smart-phone or sports car. Here in North America, super PACs and politicians spend billions of dollars in an attempt to outright ban activities such as trapping, all the while turning their backs to the millions (yes, millions) of wild animals wasted daily on our nation’s roadways. The acts of modern regulated hunting and trapping will never hold a candle to the immense suffering man’s inadvertent progression has placed upon our fragile wildlife species. Deforestation, housing development, pollution, infrastructure, and rapid population growth all take their toll on wildlife. What’s rarely reported in the media or brought up in debates is the trapper’s ever-watchful eye over our natural resources. Our tools have also evolved with ethical and humane treatment being the primary focus.

As modern trappers, we will continue to do what we know and believe to be right, and support managing our natural resources with moral wisdom. We’ll set our traps for pelts, and assume our role in modern wildlife conservation. The fur trapper lives in a modern world, and we must constantly fight being totally forgotten by our own kind. As our society continues to redefine itself, more people seem to be seeking to move further away from the daily grind and closer to the land, and I hope the interest in trapping and the understanding of its immense value will continue to grow. If the modern trapper’s solitary watch were to be removed from our woods, North America’s natural beauty would certainly lose another layer of defense against our own industrialization.

FOLLOW JEFF TRAYNOR'S "LIVE FREE AND TRAP" ON:

Here’s our roundup of Fur In The News from March 2016, and since April marks the start of the sealing…

Read More

Here's our roundup of Fur In The News from March 2016, and since April marks the start of the sealing season, of course it's in the news! Although the activists are urging Justin Trudeau to phase out the seal hunt, that's not going to happen. And that's good news for everything, including this restaurant owner who has taken to feeding a frequent seal visitor, since they are so overcrowded in the seas and they are running out of fish. Meanwhile, if you're wondering where to get your next pair of seal stilettos or seal skin bra, look no further!

Speaking of the seas, here is a highly depressing article about how whales are starving because their stomachs are full of plastic, and another piece about the impact fleece is having on marine wildlife. What is the solution? We suggest buying fur, leather, and other long-lasting biodegradable materials because as this article explains, "vegan leather" (synthetic leather to most people) isn't as ethical as its fans think.

If you are looking to buy some fur, Montreal is a great place to start, as furriers there continue to practice this traditional Canadian trade (above). And if you need some inspiration on what to buy, check out the top 6 fur coats of 2015, or the incredible garments in the Remix 2016 competition.

We can't write a roundup without talking about the animal rights warriors and, fortunately for us, it was almost all bad news for them last month. Let's start with the fact that Canada's Competition Bureau dropped the false advertising claim against Canada Goose, and the Supreme Court of Canada has given the green light to revoke the Humane Society of Canada's tax-free charitable status. (Insert fist pump here!) The mink "liberators" (read: people who set mink free to starve to death or get run over by cars) have been sentenced, one with jail time and the other house arrest and a significant fine.

In celebrity activist news, we've exposed Ricky Gervais as a fur hypocrite (above), and Pete Doherty (well known heroin addict musician) has joined the ranks of PETA by demanding a fashion brand stop using fur. Interesting that he is doing this while wearing leather shoes. And even the activists are in-fighting; this animal rights website is criticising how PETA raises its funds!

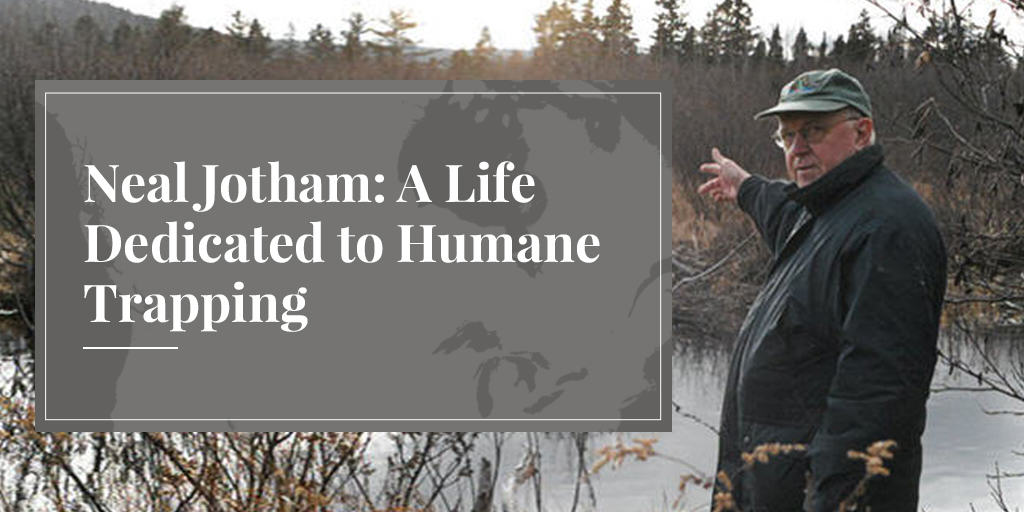

Our trapping story last month was a blog post about Neal Jotham and his work to promote humane trapping. We also released two new Q&A videos, this one about the role of trapping in keeping a balance in nature and an interview with a trap researcher.

Let's end this month's roundup with some nice looking pictures. This beautiful photo gallery in the National Post features several photos of trappers in the remote North, and what's not to love about these lovely photos (above) of a herd of wild horses discovered in Canada? And last but not least, a very touching video of a wild otter giving birth.

Fashion house Giorgio Armani announced this March it will no longer be using any fur in its products because, in the…

Read More

Fashion house Giorgio Armani announced this March it will no longer be using any fur in its products because, in the words of its patriarch and namesake, “Technological progress … allows us to have valid alternatives at our disposition that render the use of cruel practices unnecessary as regards animals.” While this tortuous explanation may sound sincere, it’s not. It’s PR bunkum. So why is Giorgio Armani really ditching fur?

OK, first I need to explain why Giorgio Armani's statement is bunkum - and add a general disclaimer that I don't actually know what went down here!

Giorgio Armani's statement is bunkum because he almost certainly never said it, or even thought it, or had a hand in picking the words. It's just part of a script prepared by his animal rights handlers.

How can I be so sure? Let’s start with some context.

• Fashion designers don't use fur for years and then quit of their own volition. There's always pressure involved from animal rightists.

• Like all fashion houses that use fur, Giorgio Armani has been harassed by animal rightists for years, but unlike some, has shown stiff resistance. Even now, its commitment to quit fur may not mean anything. In 2007, Giorgio told the press, "I spoke with the people from PETA and they showed me some materials that convinced me not to use fur." But a year later he was back with a collection of fur coats for babies! PETA responded with a poster campaign of Giorgio with a Pinocchio nose and has been gunning for him ever since.

• Giorgio Armani is a huge name in everything from ready-to-wear to haute couture, but in the world of fur is barely a player anymore. For the past several years, rabbit trim has been its thing. So quitting fur will hardly impact its collections. Add to this the fact that two major markets that have buoyed fur's revival this century are now in the doldrums (Russia) or slowing down (China), and we can say that quitting fur will have a negligible impact on Armani's profits.

Against this backdrop, we can perhaps understand the real reason Giorgio Armani is ditching fur.

As Keith Kaplan of the Fur Information Council of America explained to WWD, when designers are harassed by animal rightists, "I think they consider whether it is worth the threat of store protests and disruption of business and so forth. Right now, because of the economic conditions in Russia and China, I think designers are evaluating and saying, 'Perhaps at this juncture, it might not be. We’ll give in at this point to make this problem go away'."

And that, in a nutshell, is probably it. Giorgio Armani just wants to get the animal rights lobby of its back, at a time when the business is already tough enough.

The deal would follow what is now a standard template. The animal rights groups pen a statement to be issued in the name of the designer, claiming he has "seen the light" and will be going fur-free. The animal rightists then trumpet victory, claim full credit for their powers of persuasion, and promise to stop picketing stores and generally making the designer's life miserable.

In the case of Giorgio Armani, its decision to cave was announced by HSUS and the Fur Free Alliance, “a coalition of 40 animal protection organizations in 28 countries that are trying to end the fur trade”. “Pursuing the positive process undertaken long ago,” Giorgio's prepared script said, “my company is now taking a major step ahead, reflecting our attention to the critical issues of protecting and caring for the environment and animals.”

Had Giorgio spoken his mind, he might have said, "After years of relentless pressure, I have decided to throw in the towel and give the animal rights nuts what they want because they're a pain in the butt and I just want them to go away!”

Meanwhile, inquiring minds are still asking two questions: Is the "100% fur-free" clause in effect? And was any hidden pressure brought to bear on Giorgio Armani?

The "100% fur-free" clause is an unspoken compromise between animal rightists and designers used in closing a tough negotiation. In essence, it is agreed that the animal rightists will praise the designer for abandoning fur completely - going 100% fur-free. Meanwhile, the designer quietly continues to use fur that is a by-product of food production.

Luxury goods manufacturer Hugo Boss recently reached such a deal. In its 2014 Sustainability Report, it explained that it had been "in dialog with several animal and consumer protection organizations for many years, for example with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals." Presumably because of these "many years" of harassment (sorry, dialog), it announced that from 2016, it would be restricting the sources used for its fur supplies. Specifically, it would be "concentrating on furs that are byproducts of the food industry," while halting use of pelts from "raccoon dogs, foxes or rex rabbits". No mention was made of quitting fur, or even of reducing overall fur use.

HSUS and the Fur Free Alliance then announced that Boss was going "100 percent fur-free", a false claim that has been repeated widely, including in WWD.

SEE ALSO: IS NO FUR THE RIGHT MOVE FOR HUGO BOSS?

You might think Hugo Boss will get hauled over the coals the next time it trots out a collection of shearling (sheep fur), but it won't. Ralph Lauren, which uses an enormous amount of shearling, proves that.

FAST FACT: What is shearling? We all know that sheared beaver is the hide and hair of beaver that has been sheared to a short pile to make it lighter and less bulky, and give it a plush feel. Sheared mink is the same deal. When the hide and hair of sheep are used, it is known as shearling. All are types of FUR.

Ralph Lauren's deal with PETA, on the face of it at least, is the most shameless piece of self-serving, mutual ass-kissing in the history of the fur trade's relationship with animal rightists. A footnote in the show notes for Ralph Lauren's fall 2015 collection says it all: "Ralph Lauren has a long-standing commitment to not use fur products in our apparel and accessories. All fur-like pieces featured in the collection are constructed of shearling."

So Ralph Lauren is now "100% fur-free", and proudly compliant with "PETA guidelines" since 2006. And PETA loves Ralph Lauren right back. All Ralph Lauren has to do is stick to shearling (tons of it), while both parties insult our intelligence by pretending shearling is not fur.

Last but not least, we inevitably ask ourselves whether animal rightists finally found Giorgio's Achilles' heel. It's a reasonable question when we consider how long he held out. Maybe he really did fold because fur is not important to the company, or because the luxury fur market is slowing. Or maybe he was made an offer he couldn't refuse!

Yes, it's pure speculation, but that was the buzz when Hugo Boss made its deal. No one put it in print, or spoke it on the air waves, but people were thinking it. Could Hugo Boss have been threatened with a campaign telling the world how it got its big break?

Hugo Ferdinand Boss: Nazi Party member, sponsoring member of the SS, and admirer of Hitler. It's not much of a résumé, is it? This is the man whose company took off as an official supplier of uniforms to branches of the Nazi Party, including the Brownshirts, the SS and the Hitler Youth, using POW’s and forced labourers.

Animal rights groups know all this stuff, of course, and probably have a bunch of other cards up their sleeves just waiting to be played. And maybe they had the dirt on Armani too - we'll never know.

But one thing is for sure: Giorgio Armani did not quit fur because "Technological progress … allows us to have valid alternatives at our disposition that render the use of cruel practices unnecessary as regards animals"! As readers of Truth About Fur know, and hopefully Giorgio Armani too, technological progress – and a strong commitment by the industry – now allow us to produce beautiful furs without animal suffering.

Welcome to the fifth installment of our Hypocrites series, dedicated to exposing celebrities who use their star power to attack…

Read More

Welcome to the fifth installment of our Hypocrites series, dedicated to exposing celebrities who use their star power to attack the fur trade – while failing to see their own glaring contradictions. Today we turn the spotlight onto brash British funnyman Ricky Gervais, who fancies himself as a defender of animals. He has spoken out strongly against the use of animals in laboratories, trophy hunting, bull-fights ... and fur.

In fact, Gervais had the dubious honor of being named PETA’s “Person of the Year” in 2013, and returned the favor by providing the voice for a skinned rabbit in a recent PETA anti-fur/anti-leather video. (Fellow celeb-hypocrite Pink played a skinned alligator.)

Interestingly, Gervais hasn’t attacked other sectors of animal agriculture or the fishing industry ... maybe because he loves a Christmas feast of "roast turkey" with "little cocktail sausages wrapped in bacon, no doubt about it." Or that he regularly eats chicken, is a cheese addict, and loves fish sticks.

“Animals are not here for us to do as we please with. We are not their superiors, we are their equals. We are their family. Be kind to them,” says Gervais. Unless, of course, we fancy them breaded and fried.

(more…)Neal Jotham has played a central role in promoting animal welfare through Canada’s world-leading trap research and testing program for…

Read More

Neal Jotham has played a central role in promoting animal welfare through Canada’s world-leading trap research and testing program for the past 50 years. From his first voluntary efforts with the Canadian Association for Humane Trapping (1965-1977) and as executive director of the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (1977-1984), to chairing the scientific and technical sub-committee of the Federal-Provincial Committee for Humane Trapping (1974-81) and ISO Technical Committee 191 (1987-1997), to serving as Coordinator, Humane Trapping Programs for Environment Canada's Canadian Wildlife Service (1984-1998), and his continuing work as advisor to the Fur Institute of Canada, Neal has been a driving force. At times mistrusted by animal-welfare advocates and trappers alike, he always remained true to his original goal: to improve the animal-welfare aspects of trapping. Truth About Fur’s senior researcher Alan Herscovici asked Neal to tell us about his remarkable career as Canada’s most persistent humane-trapping proponent.

Truth About Fur: Tell us how you first got involved in working to improve the animal-welfare aspects of trapping.

Neal Jotham: It was 1965, the year the Artek film launched the seal hunt debate. I was concerned about what I saw and wrote a letter to the Fisheries Minister. A colleague – I was an architectural technologist – suggested that I send my letter to a group concerned about trapping methods, the Canadian Association for Humane Trapping (CAHT). I was invited to one of their meetings and met some wonderful volunteers including the legendary Lloyd Cook, who was then president of the Ontario Trappers Association (OTA).

Lloyd was a kind and gentle man, mentoring boy scouts about survival in the woods and introducing the first trapper training programs in Ontario. Once he rescued two beaver kits from a forest fire and raised them in his bathtub until they were old enough to release into the wild. He invited the CAHT to set up an information booth at the OTA annual convention, and he took me onto his trap line, near Barrie, Ontario.

Lloyd and I discussed how great it would be to do some proper research about how to minimize stress and injury to trapped animals. I thought it would be quite a simple matter. Little did I know that it would occupy the better part of the next 50 years of my life.

TaF: So you got involved with the CAHT?

Jotham: I was asked to serve as voluntary vice-president of administration, in charge of publicity and communications. Our main priority was to make the governments, industry and the public aware of the need for animal welfare improvements in trapping, because very few people were even talking about trapping at the time.

TaF: How did you go about raising awareness?

Jotham: We produced brochures explaining the need for improvements. We never called for a ban on trapping – we recognised the cultural, economic and ecological importance – but we were honest about the suffering the old traps could cause and the need for change.

In 1968, because governments and industry were still not engaged, CAHT joined with the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (CFHS) to establish the first multi-disciplinary trap-research program at McMaster University (to look at the engineering aspects of traps) and Guelph University (to investigate the biological factors).

In 1969, we were contacted by an Alberta trapper and wildlife photographer named Ed Cesar. He had ideas for new trap designs and also wanted to make a film about trapping that he hoped could be televised. CAHT asked if he could film animals being caught in traps, which he did.

CAHT purchased three minutes of this film and I showed it at a federal/provincial/territorial wildlife directors conference in Yellowknife, in July 1970. That resulted in an immediate $10,000 donation to the CFHS/CAHT pilot project from Mr. Charles Wilson, CEO of the Hudson’s Bay Company, then based in Winnipeg, and some smaller donations too.

TaF: But the governments still weren’t involved?

Jotham: No, so we went public. CAHT added narration and sound to the film, titled it They Take So Long to Die, and showed it on Take-30, a CBC current affairs show. That got attention, all right! In 1972, we were invited to a Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference where we were criticized for “hurting trappers”. We explained that we just wanted to make trapping more humane, we had only broadcast the film because government wasn’t listening.

TaF: How did trappers feel about your efforts?

Jotham: Many trappers understood what we were saying. In fact, Frank Conibear, a NWT trapper, had been working on new designs since the late 1920s, and by the 1950s produced a working model of the quick-killing trap that still carries his name. He got the idea from his wife’s egg-beater, the concept of “rotating frames”: if an animal walked into a big egg-beater and you turned the handle fast enough, it would be there to stay, he figured.

The Association for the Protection of Furbearing Animals (APFA) paid to make 50 prototypes of Conibear’s design and, in 1956, Eric Collier of the British Columbia Trappers Association supported field testing and promoted the new traps in Outdoor Life magazine. Lloyd Cook was another trapping leader who wrote positively about the new traps, and the CAHT offered to exchange old leg-hold traps for the new killing devices, for free.

In 1958, Frank Conibear gave his patent to the Animal Trap Company of America (later Woodstream Corporation), in Lititz, Pennsylvania – for royalties – and a light-weight, quick-killing trap became widely available for the first time. The Anti-Steel Trap League (that became Defenders of Wildlife in the 1950s) had been sounding the alarm about cruel traps since 1929, but it was trappers who did much of the earliest work.

TaF: So trappers associations supported efforts to improve traps?

Jotham: Several did. In the old days, trappers had been very jealous about guarding their secrets; you could only learn the tricks of the trade if you found an older trapper to take you under his wing. But with the emergence of associations, trappers began to share more information. They realized that everyone could benefit if trapping methods were improved. Effective quick-killing traps improved animal-welfare, of course, but they also prevented damage to the fur sometimes caused when animals struggled in holding traps. And trappers did not have to check their lines every day, like they did with live-holding (foothold) traps.

TaF: And you finally succeeded in getting the government involved?

Jotham: Yes, we did. In 1973 the creation of the ad-hoc “Federal-Provincial Committee for Humane Trapping” (FPCHT) was announced.

A five-year program was launched in 1974, with work to be done at McMaster University, in Hamilton, and at the University of Guelph, where our CFHS/CAHT pilot project had started.

I was asked to act as executive director and to chair the Scientific and Technical Sub-Committee, because we had already made some real progress in developing methodology and technology to evaluate how traps really work. For example, measuring velocities and clamping forces and other mechanical aspects of traps. In fact, at McMaster we made some important improvements to Frank Conibear’s rotating-jaw, quick-kill traps that are still used today.

TaF: And what happened to your film?

Jotham: When the government committed to funding the FPCHT we cancelled plans to distribute our film more widely. Meanwhile, we learned that Ed Caesar had staged some of the “trap line” scenes; he indicated in a letter that he had live-captured some of the animals and placed them into traps so he could film them.

Some people were disappointed that we had withdrawn our film, and the Association for the Protection of Furbearing Animals (APFA) decided to continue their campaign: they used Caesar’s staged images to make a new film, Canada’s Shame, narrated by TV celebrity Bruno Gerussi. The APFA (aka: FurBearer Defenders) has given up any pretense of working to improve trapping methods; they now oppose any use of fur. Their current position brings to mind the comment by American philosopher George Santayana: “Fanaticism consists of redoubling your efforts when you have forgotten your aim.”

TaF: So what did the FPCHT research program achieve?

Jotham: It was 1975 by the time it really got rolling, and the final report was made in June, 1981, in Charlottetown. Over that period, not only were existing traps evaluated, but a call went out to inventors to submit new trapping designs. 348 submissions were received, over 90 per cent of them from trappers! All these ideas were evaluated and 16 were retained as having real humane potential. But the FPCHT was still an ad hoc project; it was becoming clear that a more formal body would be needed to direct on-going trap research and development. So, in 1983, the federal and provincial governments agreed to create the Fur Institute of Canada (FIC), with members from government, industry and animal-welfare groups.

TaF: How did you get involved with the new Fur Institute of Canada?

Jotham: In 1977, I had become the first full-time Executive Director of the Canadian Federation of Humane Societies (CFHS), where I had a wide range of responsibilities, but of course I remained very interested in trapping. So I was pleased to serve on the founding committee of the FIC, and then to be hired by the Canadian Wildlife Service (Environment Canada) to manage the government’s funding contributions to the FIC’s newly established trap research and testing program. Initially, the Government of Canada committed $450,000 annually for three years to get things started, and this was matched by the London-based International Fur Trade Federation (IFTF).

TaF: What was new about the Fur Institute of Canada’s program?

Jotham: First, we established of the world’s first state-of-the-art trap-research facility in Vegreville, Alberta, which includes a testing compound in a natural setting. All our testing protocols were approved by the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC), the same group that approves animal research protocols in Canadian universities, hospitals and pharmaceutical laboratories.

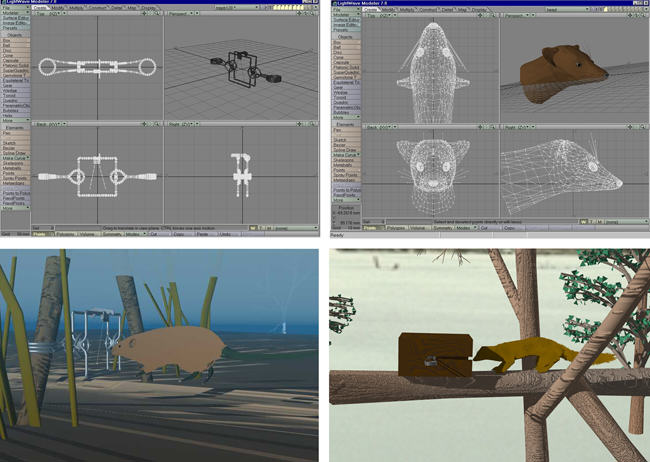

In 1995, another dramatic breakthrough was made: the researchers had collected enough data to develop algorithms that allowed evaluation of the humane potential of traps without using animals at all; we can now analyse the trap’s mechanical properties with computer simulation models. This made it unnecessary to capture, transport and house thousands of wild animals – while saving millions of dollars.

TaF: Did this research help with the formulation of the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS)?

Jotham: Canadian research was vital for the AIHTS. We had begun working on trapping standards as early as 1981, with the Canadian General Standards Board (CGSB), and by 1984 we had the first standard for killing traps. But with calls growing in Europe for a ban on leg-hold traps – and because virtually every country in the world uses trapping for various purposes – the CGSB suggested that there was a need for an international standard. To this end, ISO Technical Committee 191, of the International Organization for Standardization, was established in 1987, with yours truly as the first Chairman.

Our timing was good; by 1991, a EU Directive was being proposed that would not only ban the use of “leg-hold” traps in Europe, but would also block the import of most commercially-traded wild furs from any country that had not done the same. Because the stated goal of the legislation was to promote animal welfare – and because all EU member states permit the trapping of animals with methods basically the same as those used in Canada – Canadian diplomats succeeded in having the EU Directive amended to admit furs from countries using traps that “meet international humane trapping standards”.

The problem was that no such standards existed yet, and animal activists on ISO Technical Committee 191 refused to allow the word “humane” to be used in our documents. The deadlock was resolved by agreeing that ISO would develop only the trap-testing methodology, leaving it to individual governments to decide what animal-welfare thresholds they would require.

In 1995, the governments of the EU and the major wild-fur producing countries (Canada, the USA and Russia) developed the AIHTS, which was signed in 1997, and ratified by Canada in 1998. (For constitutional reasons, the US signed a similar but separate “Agreed Minute”.) The AIHTS explicitly requires that ISO trap-testing methodology must be used to test traps.

TaF: What are the main contributions of the AIHTS?

Jotham: The AIHTS is the world’s first international agreement on animal welfare, I think we can be very proud of that. Concerns about the humaneness of trapping that had been raised since the 1920s, are now being addressed seriously and responsibly. And, of course, the Agreement kept EU markets open for wild fur; Article 13 states that the parties will not use trade bans to resolve disputes, so long as the AIHTS is being applied. In other words, science and research, not trade bans, will be used to promote animal welfare. This is a very positive development.

TaF: And how do you feel about the Fur Institute of Canada introducing a new “Neal Jotham Award for the Advancement of Animal Welfare”, in 2015?

Jotham: It is wonderful that the trapping community has embraced animal-welfare so strongly. And the award is very gratifying personally, of course, especially when I remember how suspicious some trappers were when I first arrived at the FIC. They were convinced that I was an activist mole, while many of my old animal-welfare friends thought that I had “sold out” to the fur industry. But whether I was with the CAHT, the CFHS, the CWS or the FIC, I was always pursuing the same goal: to make trapping as humane as possible. It was a long road, but we succeeded in bringing all the stakeholders to the table to seriously address this important challenge. I think we can be very proud of what we have achieved together.

***

In 2016, Neal Jotham won a Nature Inspiration Award for Lifetime Achievement from Canada's Museum of Nature.

It’s time for our monthly Fur in the News Roundup. Here is what the media were saying about fur in February!…

Read More

It's time for our monthly Fur in the News Roundup. Here is what the media were saying about fur in February!

Let's start with fur trade history, Hollywood style. Leonardo DiCaprio won the Oscar for Best Actor on Sunday and we love that he is standing up for protecting the Earth and our lands (otherwise known as our hunting and trapping grounds). If you are interested in the history behind The Revenant, we highly recommend this article, "The true story behind 'The Revenant' is even crazier than the movie".

It is great to highlight the history of trapping, and we also love this article from The Sportsmen's Alliance about why all sportsmen need to defend trapping. Let's give the trappers the support they need right now! Because as we know, the market hasn't been great for everyone this year. Unfortunately some of the wrong animals have been getting caught in traps, but we have a great solution for this: keep your dogs on a leash and don't let them roam free on other people's private property!

Let's move on from getting caught in traps to getting caught: the two American animal rights activists who went on a cross-country anti-fur rampage have pleaded guilty and will be going to prison and paying nearly $400,000 in restitution to victims. This might be the best news of the year, and we are only in March!

And the media has been very savvy lately about the tricks of the animal rights movement. This article talks about how groups make you want to cry and then they take your money, and the following story actually did make me cry a little. It is the very sad story of a horse at his end of life, and why we should reconsider the ethics of animal rescue.

We have a new hypocrite profile: Sairey Stemp (pictured above) is the editor of the British version of Cosmopolitan magazine and wrote a long article about why she dislikes fur, meanwhile promoting leather and sheepskin in her magazine. And while we are on the topic of hypocrisy, this writer says that it is silly to be anti-Canada Goose but still eat meat. By the way, here are 5 reasons why PETA won’t make me ditch my Canada Goose.

The activists have been up to their usual shenanigans. There's one in Scotland threatening a hairdresser because she put a fox skin in her store window, and there's a group of vegans in Ontario trying to argue that they are a "creed" and that "ethical veganism" is a protected human right.

But they aren't all nuts! One of our contributors used to be on their side and now tells his story about how he turned from activist to adult. And a last blow to the activists, Greenpeace has released a study detailing the hazardous chemicals used in outdoor clothing. Even a better reason to wear fur!

And finally, on the fashion front, fur has been been everywhere! From the rise of the #realfur selfie, to the menswear catwalks of Milan and Paris, it is making its mark. Even those crazy fur shoes that everyone thought would never catch on ... yup, those guys are super popular, too.

That's it for February! Let's end with a furry friend. February 27th was International Polar Bear Day!

Here is the fourth installment of our Hypocrite series, aimed at exposing the celebrities and professionals whose anti-fur arguments have…

Read More

Here is the fourth installment of our Hypocrite series, aimed at exposing the celebrities and professionals whose anti-fur arguments have a lot of holes in them. Today we are talking about the Senior Fashion Editor of the British edition of Cosmopolitan magazine, Sairey Stemp. An email response of hers to a fur company was recently published in the Huffington Post. She had c.c.'d her email to PETA, which she suggested as a good source of information on "this highly cruel and unnecessary industry."

“I'm afraid this email has really upset me," she told the fur company. "I think you need to be aware of the extremely barbaric practices of the fur industry. I cannot and will not tolerate an industry that sees fit to torture, skin alive, electrocute and castrate innocent animals so their pelts can be used for 'fashion'.”

Now, let’s not focus on the problem that the supposed journalist didn't bother to have her work fact-checked. We all know that animals are NOT skinned alive for their fur, and PETA has even admitted that this is not a normal practice. We also won’t focus on the fact that Cosmopolitan features tons of cheap “fast fashion” clothing on its pages, clothing made under highly questionable working conditions in the Far East, from (usually petroleum-based, synthetic) materials that are filling our landfills and polluting our waterways. That is a topic for another day. This article’s about the hypocrisy of denouncing fur while featuring lots of other animal products in your magazine.

The Hypocrite: Sairey Stemp, Senior Fashion Editor of the British edition of Cosmopolitan magazine, a publication that does not feature real fur but promotes lots of other “dead animals”.

The Hypocrisy: Stemp’s anti-fur rant, published in the Huffington Post, was one of the silliest articles we've read in a long time. Devoid of facts, she spews inflammatory (and hypocritical) garbage like this: “The fur industry is one of the most barbaric, hideous, cruel and bloody industries. The reason it continues is simply because of money. If people didn't buy and wear fur, if the fashion industry didn't use and support it, then it would cease to be a viable commercial industry and the fur farms would close.”

Stemp denounces fur, but guess what her Cosmo suggests for winter coats: leather, wool and sheepskin! “But they're by-products of the food industry!” she'll cry. Someone should tell her PETA also opposes the production and eating of meat animals! (And, funny, now that we think about it, we’ve never seen sheep on the menu in England, only baby sheep.) So it’s OK to kill farmed cows and sheep for clothing, but not mink? And how about the bags and shoes that Cosmo features? Many of them are made of leather and suede, a.k.a. dead animals. Yup, according to Stemp’s Cosmo, it’s “obscene” to wear fur but you look “Stunning in Shearling.”

What they say: According to HuffPost, Stemp’s article was an “epic response” to a fur company.

What we say: Her article was a load of hypocritical drivel, with lots of copy-and-paste from a PETA press release.

Sairey, we respect your decision to dislike fur, you have every right to do that. You don’t have to wear it, no one is forcing you. You also have the right, as a Fashion Editor, to decide not to put fur on the pages of your magazine. But, please, don’t write insulting articles about the fictional horrors of the fur industry while you happily promote other apparel that is also made from “dead animals”.

If your only knowledge of fur farming comes from PETA, you don’t know anything about it. (And by the way, did you check the welfare standards of the animals used by the leather brands you promote?) Please explain why fur is so terrible, but leather and sheepskin are totally fine. Last time we checked, animals died for both, so the real question should be how responsibly the animals are treated.

Bottom line, you have a choice: you can be a shallow-thinking hypocrite or you can act like a professional journalist. If you think it’s wrong to kill animals for clothing, then stop promoting leather and sheepskin too. But if you can’t do that (because the leather companies pay your salary with their ads), then at least stop parroting PETA’s hateful drivel about fur. You can’t have it both ways!

ALSO IN OUR FUR HYPOCRITES SERIES: BRIAN McFADDEN, PINK, STELLA McCARTNEY.

It is minus 23 degrees Celsius (-32C with the wind-chill) but I am snug as a bug in my Canada…

Read More

It is minus 23 degrees Celsius (-32C with the wind-chill) but I am snug as a bug in my Canada Goose parka as I walk Maggie, our 9-year-old Labrador Retriever.

It is so cold in Montreal this Valentine’s Day weekend that I cinch my parka hood completely closed, the soft coyote fur ruff forming a cozy, protective ring around my face. The goose down stuffing keeps the rest of me warm. I wonder how our animal activist friends are enjoying the bitterly cold weather, because this is the weekend they have chosen for their National Anti-Fur Day (“Have A Heart, Don’t Wear Fur”) protests in Montreal and other cities across North America.

As a sign of the times, Canada Goose parkas are the target of choice for this year’s anti-fur rituals. Why? Because even though fewer traditional full-fur coats are being worn these days, fur is now omnipresent in smaller items, accessories and trimmings. This has made fur much more affordable, and it is now being worn by more – and younger – people than we have seen in decades. It has been democratized.

SEE ALSO: Why fur trim keeps us warm.

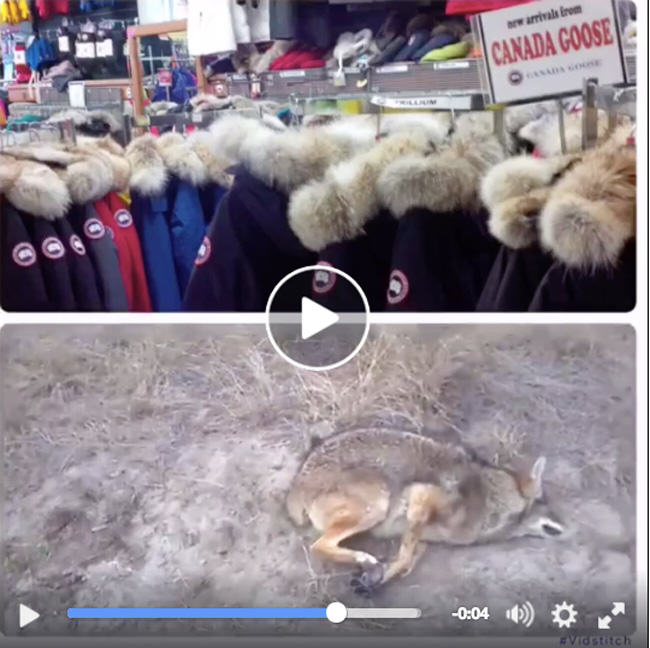

In response, PETA has unleashed a new campaign “juxtaposing Canada Goose’s coyote-fur jackets with a disturbing video of a trapped coyote suffering after being shot.” The video is prefaced with a “warning” that it contains upsetting images, but this has apparently not discouraged many of PETA's fans because, it claims, the video “has received more than 16 million views.”

To drive home PETA's message, volunteers “wearing nothing but body paint and faux-fur ears and tails” would be posing “in bloody leg-hold traps” outside retailers selling Canada Goose parkas over the weekend. According to PETA Senior Vice President Lisa Lange, “Anyone who buys or sells one of Canada Goose’s fur-and-feather jackets is responsible for these animals’ terrifying and painful deaths.”

So has PETA’s “shocking” video convinced me to give up my Canada Goose? Not a chance, and here's why:

The first problem is that PETA’s campaign video does not show a coyote “suffering after being shot”. Quite the contrary, we see the animal killed instantly with a direct shot to the head – exactly how it is supposed to be done. This is the most humane way to euthanize animals taken in restraining traps, as taught in trapper training manuals and mandated by the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS).

This is also the method proposed by the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) guidelines.

”3. Physical Methods: These techniques, when properly applied, kill rapidly and cause minimal stress. They may offer a practical solution for field euthanasia of various sized animals and prevent pharmaceuticals from entering the food chain ...

... Gunshot: While a shot to the brain of an animal produces a quick and humane death (Longair et al., 1991), it is best attempted when the animal is immobilized by injury or physical restraint.”

In other words, despite PETA's sensationalist warning – intended to shock people who have never seen an animal killed – its own video confirms that approved and humane methods are being used to euthanize coyotes.

PETA claims that “trapped coyote mothers desperate to get back to their starving pups have been known to attempt to chew off their own limbs to escape.” While this may have happened very occasionally with some species (e.g., muskrats) with older trapping systems, it never happens with modern foot-hold traps.

Furthermore, the whole "starving pups" scenario never happens with fur trapping for one simple reason: like other furbearers, coyotes are hunted for their fur in the fall and winter because that's when their fur is prime. At this time of year, their young are no longer dependent on them.

As important as the nonsense PETA does say is what it doesn't say: It omits to inform us that coyotes have expanded their range across North America and are now so abundant that they are the number one predator problem for ranchers, preying on new-born calves and lambs. It also fails to mention the increasingly frequent reports, from Toronto to Los Angeles, of coyotes carrying away pet dogs and cats.

Several states and provinces have even offered bounties to reduce over-populated coyotes.

SEE ALSO: Will urban coyotes change the animal rights debate?

Culling must be carried out both to protect livestock and pets, and also the health of coyote populations themselves. Given that coyote populations must be managed, it is surely more respectful, and responsible, to use their fur for clothing than to throw it away.

SEE ALSO: Is it ethical to produce, buy or wear fur?

The foot-hold traps used to capture coyotes (as shown in PETA’s video) are not the diabolical, steel-toothed devices that activists love to hate. Their use was banned decades ago in North America.

The new live-holding (“restraining”) traps have rubber-laminated, “off-set” jaws that do not close completely. Springs and swivels on the anchoring chain and other features have also been added to prevent injuries. In fact, these new “soft-catch” traps are commonly used by wildlife biologists to capture wolves, lynx and other furbearers for radio collaring or relocation/release into areas where they were once extirpated. Clearly they could not be used in this way if they injured animals as activists claim.

SEE ALSO: Types of traps.

Most importantly, PETA’s claims about fur are not credible because PETA is not looking for more humane ways to capture or kill animals we use. PETA opposes any use of animals, even for food or vital medical research.

PETA would have us all wear synthetic materials, most of which are derived from petroleum, a non-renewable resource. This is fundamentally anti-ecological. The modern fur trade, by contrast, is an excellent example of the sustainable use of renewable (and biodegradable) natural resources, a key ecological principle that is now promoted by all serious conservation authorities.

SEE ALSO: Fur is a sustainable natural resource.

A sixth, “bonus” point is a bit more philosophical. No one is obliged to wear fur (or leather or silk or down), but many of us appreciate the warmth and beauty of high-quality natural materials. The coyote fur and goose down in my Canada Goose coat also remind me that everything we depend upon for our survival still comes, ultimately, from nature. Thus the importance of protecting natural ecosystems for future generations.

***

UPDATE: Animal activists lodged a complaint with the Competition Bureau (the Canadian federal regulator) accusing Canada Goose of “false advertising” for claiming on its website that its furs are collected by licensed trappers using humane methods. We are pleased to report that this complaint was rejected by the Competition Bureau. See: Competition Bureau drops inquiry into false advertising claim against Canada Goose, by Christina Stevens, Global News, Mar. 10, 2016.

COMMENTS: Comments are now closed for this post.

Don’t give up on animal activists. People change. I know because I was an animal activist, and I’ve spent the…

Read More

Don’t give up on animal activists. People change. I know because I was an animal activist, and I’ve spent the last 24 years doing PR for animal users, including the last 18 for the fur trade. I’m telling my story in the hope you will reach out to that unkempt youth with a placard outside your fur store or farm. Because that person was once me, and someone reached out and opened my eyes.

***

A wise person, some say Winston Churchill, once said, "If you're not a liberal when you're 25, you have no heart. If you're not a conservative by the time you're 35, you have no brain."

Yes, it’s a sweeping statement, but there’s a kernel of truth in it for many of us.

There’s also a kernel of truth in my less-pithy variant. If you’re 25 and have never even considered the possibility that it may be wrong to kill animals for food and clothing, you have no heart. If you’re 35 and still can’t decide, no, it doesn’t mean you have no brain. You just need to wait for the right formative moments.

This is a journey I’ve taken in life, and I’m sure it’s a common one, especially for people who were not born into hunting or ranching. I come from England, not Saskatchewan or Montana. My father was an insurance claims assessor and my mother a nurse, and terms like “gun range” or “conibear” weren’t in our vocabulary. I never viewed the taking of animal life as an everyday event, but a leg of lamb on Sunday was one of my happiest childhood memories. With freshly made mint sauce!

But I wasn’t totally sheltered either. We had an acre of land and some livestock, so I soon learned how to kill a chicken. And Dad was a keen fly fisherman, so I could kill a trout too.

He also taught me to respect animal life and the meaning of conservation. He helped me build my birds’ egg collection, but with rules. For example, never take an egg if it was the only one in the nest, or if I already had it in my collection. And anything I killed I ate, which was an easy rule to follow because I only ever killed chickens and trout.

During my teens, nothing happened to shape my view on the taking of animal life, and why would it? My head was full of motorbikes, girls, beer and cigarettes.

Then came my first formative moment, at age 21, though I had no idea it was happening, perhaps because it still revolved around girls.

A friend, Tim, had become a fox hunt saboteur and was having a great time, but it wasn’t because he was saving foxes. It turned out hunt sabbing was a great way to meet crazy girls! Since I already knew more than enough crazy girls, I wasn’t interested in joining, but he started preaching and it sunk in. The secret to picking up hunt sab girls, he explained, was to be passionate in your hatred of three things: fur, veal and whaling.

I doubt he really hated these things, but he planted a seed in my brain that fur and veal were cruel, and all whales were being hunted to extinction. Since I didn’t know anyone who wore fur, ate veal, or had even seen a whale, I never questioned Tim, and no one else ever tried to set me straight.

In hindsight, the only truth I gleaned from Tim was that girls like “sensitive” guys, and “sensitive” guys “love” animals. This I still believe to be true!

At age 26, I was living in Italy and picking up my lady to go to a party. As always, she was casual but glamorous, with her big Stefanie Powers hair, but there was this thing draped around her neck. It was grandma’s fox stole, she said, but it was so much more. To be precise, it was a head, four paws, and a tail more!

I remember feeling instant revulsion, but why? Was it just Tim’s anti-fur indoctrination surfacing, or was it a visceral reaction to that head, paws and tail? Probably a bit of both. Whatever the case, I asked her to remove it, which she did, without question. And that was the first and last time I made a stand against fur.

My stand against veal was even less distinguished. I’d seen it on menus a few times, and all I had to do to lodge my protest was not to order it. Then one day a friend’s date ordered it, and I mumbled something about being opposed. So she asked if I’d ever tried it, and offered me a taste. I ate it, liked it, and that was the end of anti-veal activist me.

All in all, I was a pathetic animal activist, no doubt about it. I needed a cause I believed in! Maybe I was instead destined to be a conservationist, and my only cause left standing was whales. Since there were only a handful left and Japan wanted to kill them all, surely even I could follow through!

And then, as fate would have it, at age 29 I landed a job in Tokyo with a trade paper owned by one of Japan’s largest newspapers, the Asahi Shimbun. The country’s whaling fleet was embarking on its last season of commercial operations in the Antarctic, and the Asahi Shimbun was honouring them with a photo exhibit in its atrium.

At last I could do the right thing! I made up some signs saying “STOP WHALING NOW”, and late one evening plastered them all over the photo exhibit.

The next morning, of course, they were all gone, but a Canadian lady in my office had seen them and suspected me as the culprit. I confessed, and why wouldn’t I? I was proud!

Well, that bubble was soon burst. What kind of whales are they catching? she asked. No idea. Do you know the whales they’re catching are abundant? I did not know that. What do you think they use them for, oil? Yup. Wrong! And on it went.

In fact, I didn’t know anything at all.

My eyes were opened. There I was, striving to become a journalist without any formal training, but fully aware that I had to know my subject. I needed to apply the same rigour to my personal beliefs as I did to my profession, particularly if I was going to judge others.

To cut a long story short, within seven years of my humiliating one-man anti-whaling campaign, I found myself in the Antarctic with the Japanese whaling fleet, filming for the BBC and mucking in as a flenser, feeding strips of skin and blubber through a trimming machine. Greenpeace filmed us, and I filmed Greenpeace.

There followed a five-year stint working for Japan’s Institute of Cetacean Research, while doing PR at meetings of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) for a Norway-based NGO, the High North Alliance.

Before I even returned from the Antarctic, I already knew that a lot of the information being disseminated by whaling opponents was nonsense. I also soon learned that IWC meetings were mostly about political horse-trading, a little about conservation, and nothing to do with its mandate, which was to regulate an industry.

So step one in my conversion from a whaling opponent to a supporter was to sort fact from fiction. It took me years, but here’s a time-saving tip for newcomers. Any materials you’ve gathered from groups like the International Fund for Animal Welfare and the Humane Society of the US go straight in the bin. Nothing to be learned there. Instead, head straight for the reports of the IWC Scientific Committee (not the IWC itself).

And if your line of research is the same as mine was, you’ll learn that restrictions on catches going back to the 1960s (when the IWC still functioned as an industry regulator) have made it extraordinarily unlikely that any species of whale will now go extinct. The last population to have been extirpated was of gray whales in the North Atlantic, and that was in the early 18th century. You’ll also learn that minke whales in the Antarctic, as caught by Japan, are generally believed to be more plentiful now than ever before.

At some point you will also inevitably run into a concept that underpins the majority of conservation programs today, and which clarified everything for me: “sustainable use of renewable natural resources”. Few people knew this term back then, but thankfully anyone involved today, in whatever way, with natural resources knows what it means, so we can use the shorthand “sustainable use”.

The importance of this concept cannot be overstated. “Conservation” is great, but says nothing about how we can, or can’t, use natural resources, and so is often misunderstood as a synonym for “protectionism”. But “sustainable use” clearly recognises the incentive for humans to preserve nature by giving it value as a source of sustenance.

Also important in my education was exposure to cultures that are intertwined with animals.

Six months on a ship with 250 whalers and marine biologists was an excellent start. Stays in whaling communities in Japan, Norway, Iceland, the US and South Korea added more context. (Did you really believe only Japan goes whaling?)

In the 20 years since I moved on from whaling, I’ve come to know sealers, trappers, fur farmers, fox hunters, and fishermen.

For two years I worked in Zimbabwe with rural communities that live in daily dread of rogue elephants trampling their crops and destroying their homes. There’s no quicker way of changing a negative view of trophy hunting than seeing a rich hunter fly in and pay $20,000 to a poor village to kill an elephant that would have been killed anyway.

Now let’s rewind.

Many years earlier, some crazy girls had told Tim that fur, veal and whaling were bad, and he’d believed them. Tim told me and I believed him. Not only does this not surprise me now, but I’d be surprised if it had happened any other way.

Neither of us came from hunting or farming backgrounds, or had marine biologists for parents.

We would also have been naïve. We are not born with the knowledge that advocacy groups don’t always tell the whole truth. It is knowledge we acquire, in the same way we learn that politicians cannot be trusted, our teachers make mistakes, and our parents are human. Do you remember as a youth arguing with a friend about some fact until he showed it to you in the newspaper? That was it, argument over. If it was in print, it must be true. You don’t think that anymore, right?

So with animal rights groups churning out PR materials by the ton, mostly aimed at impressionable youths, and industry advocacy groups always lagging behind, we should not be surprised if the next generation of conservationists starts out by believing whales are going extinct, seals are skinned alive, and killer whales and wolves are really quite friendly if you give them a chance.

As for learning through exposure to different cultures, that too takes time. I met my first dairy farmer when I was 5, but it would be another 30 years before I’d meet my first whaler and first sealer, and take my first trip on a long-liner. I’m now 59 and still haven’t gone out on a trap line, but I hope that will happen too, one day.

From a pathetic but well-intentioned animal activist, I have become what I can only call a veteran advocate for animal use. Critics may say I’ve done a turnaround, a 180, or that I’ve sold out. But they’d be wrong.

I haven’t undergone any fundamental changes in values. I haven’t embraced any new truths.

At heart, I am the same conservationist I always was, and if all whales were actually threatened with extinction, I’d be back out with my signs in an instant, calling for a ban on whaling.

And my respect for animal life has remained constant throughout my life. Whenever I hear of animal abuse, I am as disgusted as the next feeling person, and if the offender is involved in an industry that happens to be paying my bills, I feel betrayed.

I do not believe we have an inalienable right to take animal life for whatever purpose we desire. But I do believe we have a right to use animals in a sustainable, humane manner to meet our basic needs, and that includes enjoying a leg of lamb on Sunday.

So I haven't really changed at all. I just grew up.

And those activists outside your fur store or farm will grow up too. They’ve already taken the first important step of thinking about the taking of animal life, so they have a heart. And yes, they do have brains. They just need guidance, and who knows, they might become the next generation of animal use advocates. Don’t give up on them.

It’s time to look back at last month’s media, so here is our Fur in the News roundup for January…

Read More

It's time to look back at last month's media, so here is our Fur in the News roundup for January 2016! Let's start with some cinema. The Revenant has been one of the most talked-about Hollywood films in the fur and trapping communities. Here's a Vanity Fair piece about the costumes for the film, the secret concoction they used in lieu of bear grease, and the grizzly pelt Leonardo DiCaprio's character Hugh Glass wore throughout the film.

St. Louis Public Radio has found quite a few connections between the city and the fur trade of the film's era. And what's not to love about Leonardo DiCaprio's acceptance speech when he won Best Actor at the Golden Globes?

Since we are on the subject of costumes, quite a few publications identified fur as being one of the trends on the recent menswear fashion shows. While we wouldn't exactly consider ourselves fans of Kim Kardashian, we love that she dresses herself and her daughter in beautiful fur coats.

If you don't have $10,000 for a new jacket, then why not try making one yourself? This is a brand that sells fur accessories, but what is stopping you making some of your own? Or how about a cushion? StyleCaster has some great ideas on how to decorate your home with fur.

While fur may be in fashion, not all the shops have been thrilled with sales. The warm weather in North America has had a negative impact on fur sales at retail. But it is not all bad! This French fur retailer (pictured above) has been doing very well with its fur-lined parkas, and we love the story of this Canadian furrier repurposing old fur coats into blankets. I can't think of a better way to stay warm in bed!

Vancouver fur retailers got some great news when this animal rights activist was banned by police from entering, or even walking by, any of the fur stores he has been harassing for the past few years.

Speaking of crazy animal rights activists, a group of them in Shanghai forced some "animal abusers" to eat cat poop, only to find out later that they had targeted the wrong people. Now they are up sh*t creek, pending sentencing after they pleaded guilty for being total idiots.

But that's not all the activists have been up to! A heinous activist, whose name I don't even care to mention, made some horrible comments about two hunters, including country singer Craig Strickland, who went missing when their boat capsized during a duck hunt.

PETA launched a new video (pictured above) showing a violent scene where a woman gets brutally beaten up to push its anti-wool agenda. It is truly sickening. But on the bright side, PETA has had some problems with its recent mink farm allegations. It released a video depicting "animal abuse" at a farm in Wisconsin, so investigators were sent in. Its expert fur farm investigator found no violations and instead asked PETA to provide its unedited video content and make the witness available for questioning. If PETA really cared about the welfare of animals, it would provide this, but knowing PETA, it probably won't.

In trapping news, Illinois has allowed its first season of otter trapping since the species' return. Meanwhile trappers in Canada are having trouble accessing their trap lines due to mild weather. We love this amazing video of a group of trappers releasing a wolf caught in a trap.

And since we are talking about wild fur, seal skin is doing well at the auctions in Copenhagen, and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau was seen trying on a seal skin vest (see below).

Ever had to call a trapper to deal with a nuisance animal problem? Check out our blog post about wildlife control experts vs. trappers.

And here's something to bookmark: 5 Reasons Why It’s Ridiculous to Claim Animals are Skinned Alive. We wrote this piece so that everyone has a resource they can refer to when they are trying to explain to people that animals are NEVER skinned alive. We all know it never happens in our industry, but the activists have done such a good job of making everyone think it does. It is time to fight back.

And that's it for January! Let's end it with this beautiful deer dancing. Or is it an elk? Or are elk a type of deer? It doesn't matter today. We just love how cute this guy is.

If there’s a beaver dam in your neighbourhood, or your septic field really don’t look good, who you gonna call? A…

Read More

If there's a beaver dam in your neighbourhood, or your septic field really don't look good, who you gonna call? A wildlife control expert or trapper? Or is the only difference in the length of his beard?

"This is my friend Ross and he's a trapper."

This is my introduction to the lady standing in front of me. As I watch her eyes, I realize she is floating between her polite manners and her abhorrence of my title, not yet decided whether she will shake my hand. She takes a step back. After all, "He's a trapper!"

My mind smiles as I recall, not three days past, being introduced by a friend from the University of Alberta to someone else. Only in this case I was introduced with the title of “wildlife control expert”. In that case, the lady was smiling and taking a step forward with out-stretched hand, saying, “Well hello Ross, what a pleasure it is to meet you. What an interesting profession. I would love to learn more about what you do and how you deal with wildlife.”

I consider myself very fortunate to have spent most of my life with wildlife. As a matter of fact, it’s been even better than I could have imagined. I could never have planned a life quite like this, but it sure has been a great time of learning.

Wearing two hats, out of the same office so to speak, has given me a chance to see such contrasting experiences. I reflect back upon one of those that stayed etched in my memory.

Several years back, I received a call from a farmer who had been given my number by Fish and Wildlife. He needed help with a beaver problem so we set up a time and I drove out to visit. I could see from the roadway that the beaver had already dammed up the creek and the water had backed up causing flooding and erosion. As we walked he told me how, four years prior, his family had been so excited when they had first spotted beaver swimming in their creek. His children could watch from their tree fort in the fall as the beaver cut down the trees and pulled them along as they swam.

That first year, he went on to share, he was quite pleased to see that as the beaver dammed up the small creek, it held back enough water to make it easier for his cattle to drink. He felt he had a couple of water managers working with him on the farm.

As we walked up to where the creek separated a hay field, I could now see that the beaver had plugged up the crossing. The roadway was completely washed out. The trees along this “now pond” were laying all criss-crossed throughout the banks, with not much chance of anything getting down to the water without climbing over stumps and de-barked dead aspen. As I stood there, looking over this mess, he told me that two of his cows had broken their legs after falling through the banks, and as I climbed down I could see the bank had caved in from where the beaver had undermined it.

We made our way back over the fields talking about the over-population of the beaver, and I explained that if we could wait a couple more months it would be winter and we could trap them and the pelts would not be wasted. If we took the beaver now, the pelts would have no market value and be wasted. He understood and agreed, knowing it made sense to wait. Removing them at the opportune time would allow the land to recover and the pelts would be utilized.

He suggested I take a trip down the road and view another beaver lodge he had seen and inquired if I believed those beaver might also over-populate and end up migrating over to his area. I assured him that this is the usual course of action when it comes to beaver in this situation. I agreed to go visit the site and assess it for activity. He did not know the landowners there, as they were new to the area from the city. I obtained the directions and off I went, assuring him I would return in a couple of months to begin.

Upon traveling down another gravel road, I arrived on the doorstep of the neighbours. The door opened and a couple inquired what I wanted. I told them I was a trapper and that their neighbour down the road was having issues with beaver causing flooding and damming. I asked if they might like to me to deal with their beaver colony, as in a short time these also would cause flooding and damming on their property.

The response was a look of horror and a quick explanation about their reasons of refusal. They had recently bought the land to enjoy nature in all its forms and there would be absolutely no trapping on their land as long as they were the owners. I quickly apologized, said I could see that I had upset them, and left. As I gazed across the land, I could see a current beaver lodge on the far side of their creek bank and already they had felled some aspen trees that were lying down.

Driving away, I had a strange feeling while I gazed at my reflection in the mirror. Somehow my mind wandered to a decision I’d made that year to grow a beard. I even decided that I most likely looked a little rough, maybe along the lines of a mountain man, deciding that this presentation had not helped my acceptance during the discussion with this couple who had shut the door firmly in my face.

Onward I went, fulfilling the request of the farmer and eliminating the problem beaver on his land. There was no waste as I prepared all the pelts I’d taken for market.

Forward two years, it's spring-time and my phone rings. The woman on the other end of the line was sounding quite desperate. She told me she had obtained my number from Fish and Wildlife, who had informed her I was a Wildlife Damage Control expert. She quickly brought me up to speed on the dire situation out at their acreage. They had been flooded out by some beaver and needed my help as soon as possible! I regretfully advised her that the timing wasn’t good as I was extremely busy working on a wolf predation issue with Fish and Wildlife and could I contact her as soon as I had some free time? It was then she begged me, pleading with me to come at least just to look. “We are desperate for help!” she exclaimed.

So off I went next morning, following the directions she’d provided, and as I reviewed my county map I had a sense I’d visited that area before. And then I realized where I was going. I turned down the gravel road and drove up to the exact same house I had visited a couple years earlier. I could readily see the mess the beaver had made from the road. A huge pond was now located where a field had been before, and the water level was above the fence posts. The pond was so large it was not far from the yard.

I thought, “Well this should be interesting.” I parked and made my way to the house, and as I approached the man came out and thanked me for coming on such short notice, all the while shaking my hand. His wife followed and as she also began thanking me, I wondered if they would say something about the last time I was here. I then realized, “They don’t recognize me!”

So I stood there feeling awkward and decided it just wasn’t worth bringing up at this point. I figured, maybe because now I was clean-shaven and didn’t have my old hat on, they didn’t make the link. He said he would show me where the beaver lodge was. I told him I could see it from there and asked if they had thought about how they wanted to control them. He looked at me with a puzzled expression and asked, “What do you mean?” I said, “Well, they are good little water managers and have just overpopulated, but, properly managed, they could be good to have around.”

His wife responded with a resounding, “No, I want them out of here. We had no idea they would do this! We can't even flush our toilet! They have flooded the whole place and the water has backed up the septic field.”

As I stood there listening, something snapped in the back of my head and I let it go. “You folks don’t remember me, do you?” I said. His reply: "Should we?” I said, “Yes, I was here a couple of years back, a scruffy-looking fellow with a beard and cowboy hat. A trapper?”

They gazed at each other while I continued. “I came here to talk to you in the fall about managing the beaver, and you wanted nothing to do with me, shutting the door in my face. Now that your toilet won’t flush, you don’t care about nature any longer! You are asking me to go in now, in the spring, while the young are still nursing, and remove them. The young will starve to death in the lodge without their mother’s milk, and all because your toilet won't flush!”

ALSO BY ROSS HINTER: SHOULD WE BE TRAPPING WOLVES IN CANADA?

I told them that, as a trapper, I understood there was a season to manage animals and that I would not trap them in the spring. They would have to find another trapper or wait until the fall before I would return and trap the beaver humanely.