5 Reasons Why It’s Ridiculous to Claim Animals are Skinned Alive

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeOne of the most insulting and insidious lies spread by animal activists is that animals are “skinned alive” for their…

Read More

One of the most insulting and insidious lies spread by animal activists is that animals are “skinned alive” for their fur. The origins of this vicious lie go back fully 50 years, to the first seal-hunt protests, and those charges were soon proved to be false, as we will explain soon.

Ten years ago, the old myth was revived – this time about Asiatic raccoons. Since then, activists have become more and more extravagant, claiming (and, no doubt, believing) that rabbits, mink and other species are also treated cruelly, including being skinned alive.

One of the main goals of Truth About Fur is to debunk falsehoods about the fur industry, so let's make something perfectly clear: Animals are NOT skinned alive for their fur. Period.

Here are some of the reasons why it is absolutely ridiculous to even suggest it.

1. It would be completely inhumane

Contrary to what activists would have us believe, most farmers take great pride in what they do; they take good care of their animals and treat them with respect. After all, their livelihoods depend on these animals, and the only way to produce the high quality of mink and fox for which North America is known is by providing them with excellent nutrition and care. When you work hard to care for animals – seven days a week, 52 weeks a year – you certainly don’t want to see them suffer.

It is therefore completely ignorant (and insulting) to claim that farmers would treat their animals with cruelty. They certainly would never skin an animal alive!

SEE ALSO: Is PETA's Angora rabbit video staged?

2. It would be dangerous for the operator

If respect for the animals and normal compassion were not enough to ensure that animals are not skinned alive, the farmer's self-interest would be. A live and conscious animal will move, putting the farmer at risk of being bitten or scratched or cut with his own knife – creating a real risk of infection or disease transmission.

Why would anyone expose themselves to such risks by skinning a live animal? The answer, of course, is that they don't!

3. It would take longer and be less efficient

We've already explained the dangers of skinning a live animal – only common sense when you think about it – but let's also take a moment to consider how difficult it would be.

Farming is a business and, like in most businesses, it is important to be efficient. Clearly it must be faster to skin an animal after it's been euthanized. It is also important to understand that the skinning of a mink or other fur animal must be done very carefully, to avoid nicks and other damage that would lower the value of the fur.

So, again, why would anyone skin a live animal? Quite apart from the cruelty, it would make no business sense whatsoever.

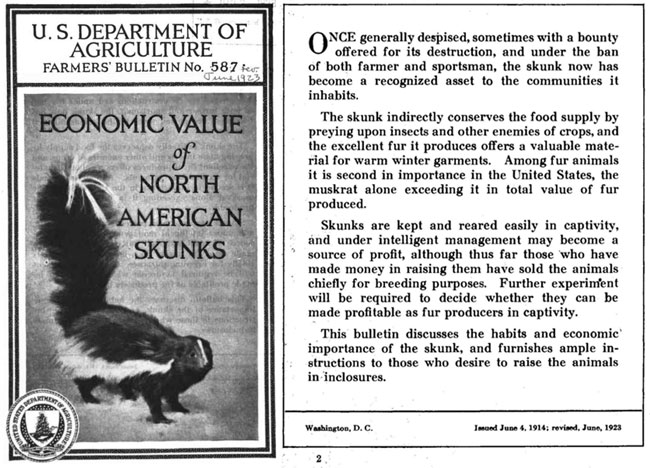

4. It would spoil the fur

While activists like to accuse farmers of being greedy ("killing animals for profit!"), they don't seem to understand that skinning animals alive would work against the farmer's financial interest.

Today’s international markets are very competitive. The amount you earn for your fur is determined by a number of factors including pelt size, fur quality, colour ... and damage. But the heart of a live animal would be beating and pumping blood; attempting to skin a live animal would therefore unnecessarily stain the fur. Yet another reason why animals are not skinned alive.

5. It's illegal

In North America, Europe, and most other regions it is illegal to cause unnecessary suffering to an animal. Skinning an animal alive is therefore not only inhumane and immoral – it's clearly illegal. Yet another reason why animals are not skinned alive.

But what about that video?

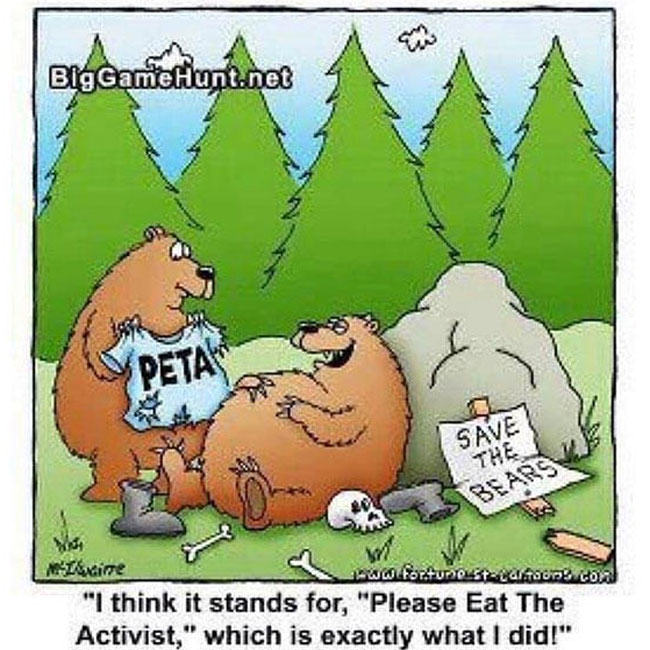

Activists frequently cite a horrific video taken in a village somewhere in China as "proof" that animals are skinned alive in the fur industry. When this video was first shown, in 2005, fur industry officials contacted the European animal-protection group that released it. They asked for a complete, uncut version of the video, as well as for information about when and where it was filmed, so a proper investigation could be conducted.

Unfortunately, the activists refused to provide this information. Strange.

If animal welfare was really their goal, wouldn’t you think they would want a full investigation? And if this was really common practice, why has there never been another video showing this type of cruelty? (Even PETA now concedes skinning alive is not common practice, but still insists it happens on fur farms because workers are rushed. In fact, euthanized mink and other farmed fur animals are usually laid out on the wire tops of their pens to cool thoroughly before pelting; otherwise the fur can be damaged or fall out after tanning.)

Combined with the facts outlined above, the only reasonable conclusion is that the cruel actions shown in this video were staged for the camera. That would be a sick thing to do, but it wouldn’t be the first time.

The film that launched the first anti-seal hunt campaigns, in 1964, showed a live seal being poked with a knife – “skinned alive”, the activists cried! But a few years later the hunter, Gustave Poirier, testified under oath to a Canadian Parliamentary committee of enquiry that he had been paid by the film-makers to poke at the live seal, something he said he would otherwise never have done. [For more on this, see Alan Herscovici's book, Second Nature: The Animal-Rights Controversy (CBC 1985; General Publishing, 1991), pg 76.]

The moral of the story? No matter how you look at it, even from the perspective of self-interest and "greed", it is ridiculous to claim that animals are skinned alive. Now you know. And so do our activist friends who monitor these pages.

UPDATE: "Film denouncing fur deemed 'staged' by IFF investigators". Women's Wear Daily, March 5, 2019. Watch an IFF video exposing the fake here:

* * *

EDITOR'S NOTE: Due to a large volume of comments received in September 2016 that contributed nothing to the discussion, we have chosen to close comments for this post.