Hair density has always fascinated the fur trade because the densest furs are also the softest and most luxurious. Before the advent…

Read More

Hair density has always fascinated the fur trade because the densest furs are also the softest and most luxurious. Before the advent of modern conservationism, this meant that the densest furs were prone to over-harvesting. Today, we have learned from past mistakes. Trade in the densest fur of all is still restricted, but the animal's recovery is considered a great conservation success. And due to a remarkable story in the history of farming, the second-densest is abundant and readily available.

To appreciate what makes fur dense, let’s set a baseline: human hair. And because human hair varies depending on ethnicity and hair colour, we’ll choose the densest of all, a pale blond(e).

A blonde’s fine hairs average about 190 per cm2, varying depending on the part of the scalp. That's almost double Afro-textured hair, the least dense.

Now step aside blondie, and make way for that benchmark of luxury, mink.

A mink’s hair density varies by season and body part. Also, farmed mink is denser than wild, and a dressed pelt is denser than a live animal. But as a guide, a dressed, farmed pelt has about 24,000 hairs per cm2. That’s 126 times denser than the thickest human pelage!

Impressed? Well hold on. Prepare for furs so dense and soft that words to describe them are hard to find. Like talcum powder, perhaps?

SEE ALSO: WHY IS AMERICAN MINK THE WORLD'S FAVOURITE FUR?

Chinchilla

Animals with the densest furs live where climates are cold, humid and windy. Size also matters; because small mammals are more vulnerable to heat loss, they generally have denser fur.

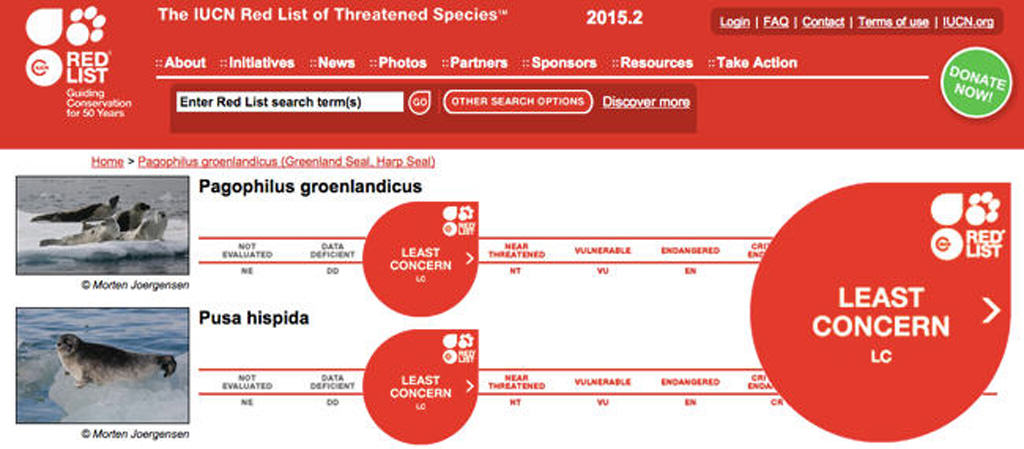

And so we find ourselves in the high Andes, home of the long-tailed Chinchilla lanigera and short-tailed Chinchilla chinchilla. Being small and nocturnal makes them elusive. They're also very rare. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies both as "critically endangered".

We can blame the “tragedy of the commons” for that. Though the term was coined for what happens when no one owns common grazing land, it also played a role in the historic fur trade.

Spanish explorers first sent chinchilla pelts home in the 16th century, but it wasn’t until the late 19th century that Europeans developed an insatiable appetite for them. Populations collapsed, prices soared, and by the early 20th century a peasant trapper could feed his family for a month with just one pelt - if he could find one!

Only late in the day, in 1910, did the range states of Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Peru unite to ban the trade, but effective enforcement was still decades away. Extinction seemed inevitable.

Farmers to the Rescue!

And then the cavalry arrived, in the unlikely form of fur farmers.

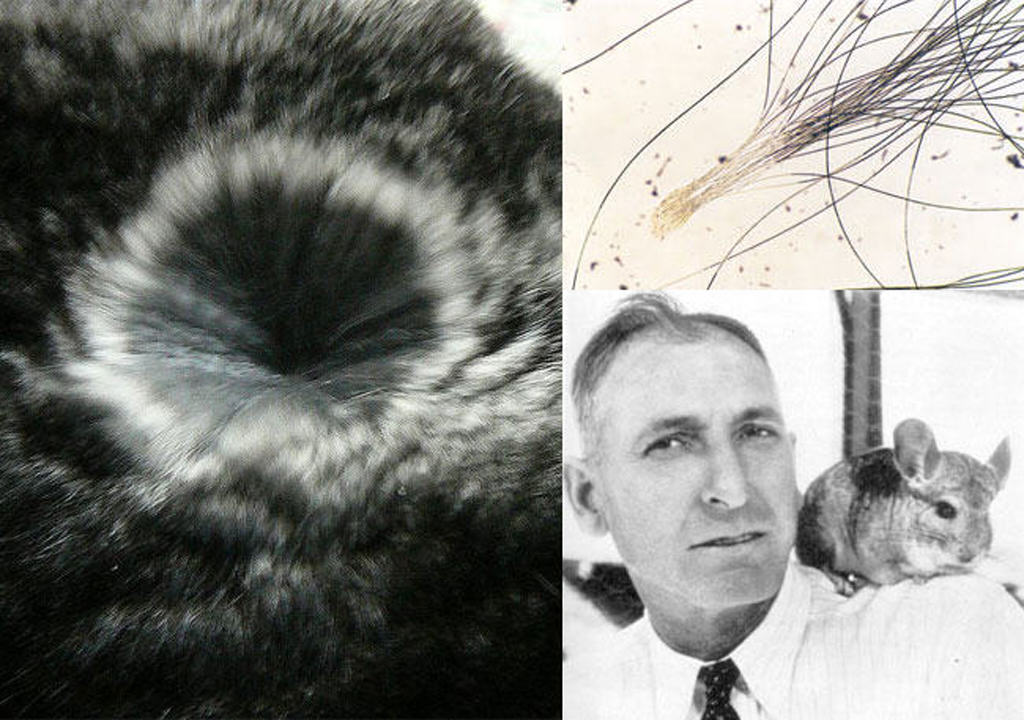

It all began with Californian miner Mathias Chapman who, in 1923, was allowed by Chile to take 11 live chinchilla home for breeding. (It took him three years to trap them!) Ten survived the trip and one gave birth en route.

Chapman originally planned to breed pets, but he switched to fur farming. Today, chinchilla farms are found from Canada to Argentina, and in many European countries, and almost all their stock are believed to descend from Chapman's original 10.

Farming of animals can help conserve their wild cousins. By meeting demand, it reduces pressure on wild populations, as in the case of mink and fox. But it can also encourage illegal hunting and provide a cover for smuggling - the fear with tiger farming.

In the case of chinchilla, farming didn't just help protect wild populations, it probably saved them. And even if most chinchilla now live in pens and eat hay and pellets, there is absolutely no chance of them going extinct!

Dense Is Desirable

So what is all the fuss about with chinchilla fur? Hair density. No other terrestrial mammal comes close.

Hairs grow from organs called follicles which, in humans, are densest on the forehead – about 290 per cm2. Chinchilla have as many as 1,000.

Then there's the number of hairs per follicle. Hairs grow in tufts, with 1-3 (rarely 4) sprouting from each human head follicle. But a regular chinchilla has about 50 hairs per follicle, while a show “chin” (as pet owners call them) may have 100.

That means a regular chin has 50,000 per cm2 - double a farmed, dressed mink pelt, and 263 times more than our human blonde. So dense is a chin's fur that it's said fleas and ticks can’t penetrate it, and if they could, they'd suffocate!

"Soft Gold"

Amazingly, there is fur even denser than chinchilla - so dense it drove men to endure the harshest conditions nature could throw at them, far from home, for more than 100 years. This was the Great Hunt!

In the early 18th century, Russian fur traders found themselves on the Pacific shores of Siberia. Drawn by a cornucopia of desirable furs, notably sable, they had spent 150 years opening up Russia's vast eastern territory.

Now they took to their boats in pursuit of fur so dense, and so valuable, it was known as "soft gold": sea otter.

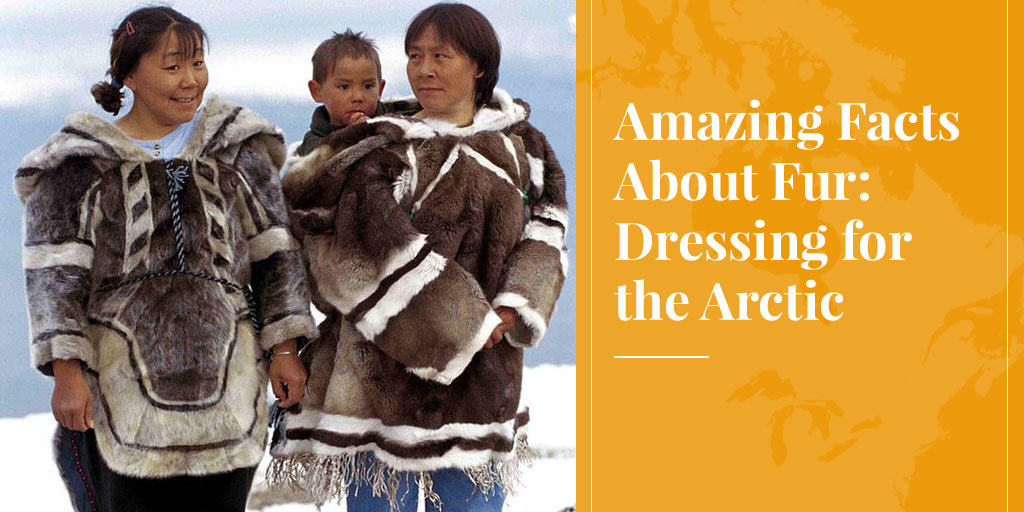

SEE ALSO: AMAZING FACTS ABOUT FUR: DRESSING FOR THE ARCTIC

Starting from the Kuril Islands, the traders island-hopped across the North Pacific, harvesting one otter population after another, plus highly profitable hair seals they found along the way. The otter trade in Alaska boomed, and then the traders headed south. There they were joined by adventurers from all over North America and Europe in the great California Fur Rush.

The moniker "soft gold" was deserved. In 1775 otter pelts sold in the Russian port of Okhotsk at up to 30 times the price of sable. In the 1880s, a pelt brought $165 in London, but by 1903, as supplies dried up, made a staggering $1,125.

Thankfully the ground-breaking North Pacific Fur Seal Convention of 1911 put an end to seal otter fever by imposing a moratorium on the hunt. But was it too late? Perhaps fewer than 2,000 otters remained. Could they ever recover?

Yes they could! Sea otters have rebounded in two-thirds of their historic range, and are today cited as a great success story in the annals of marine conservation. As a precaution given the lesson of history, IUCN still classifies them as endangered, but Alaskan fishermen are now complaining the population is growing so fast, they've become a pest!

Exempted from the hunting ban, Alaskan coastal communities are also building a highly regulated trade in sea otter handicrafts and garments.

So what is it about sea otter fur that's so alluring? You know the answer already: density. Not even chinchilla compares.

Sea otters need superb insulation because, unlike other marine mammals, they have no blubber. And unlike that other four-legged marine mammal, the polar bear, they don't leave the water unless they absolutely have to. Imagine, swimming in the North Pacific, 24/7, in winter. Unless you have inches of blubber, or are a halibut, it's almost inconceivable.

And that's why sea otters have the greatest follicle density of any mammal, and hair density that ranges from 100,000 per cm2 on the legs and chest up to 400,000 on the sides and rump.

At its upper range, that’s four times denser than the finest show chin, 16 times denser than a farmed mink, and 2,105 times denser than our human blonde. That is dense fur!

***

FURTHER READING

Alaskan native Peter Paul Kawagaelg Williams, founder of Shaman Furs, is in a special position to bring sea otter to the international fashion scene. By Vanessa Friedman, New York Times, Dec. 1, 2016.