On July 28-29, the Fur Institute of Canada descended on Whitehorse, Yukon, for its first in-person Annual General Meeting in…

Read More

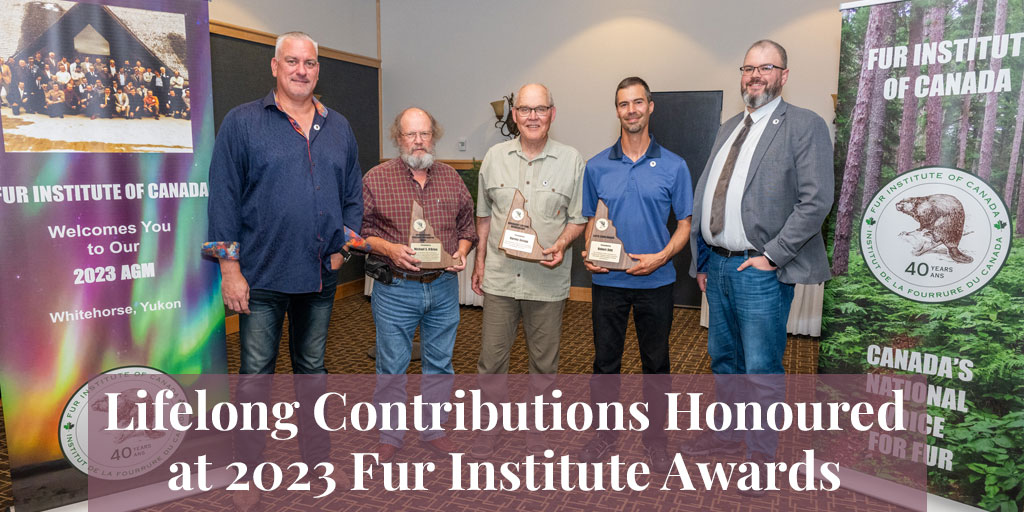

On July 28-29, the Fur Institute of Canada descended on Whitehorse, Yukon, for its first in-person Annual General Meeting in three years, and also to mark its 40th anniversary. As part of the celebrations it revived its Awards Program, honouring lifelong contributions to the fur trade.

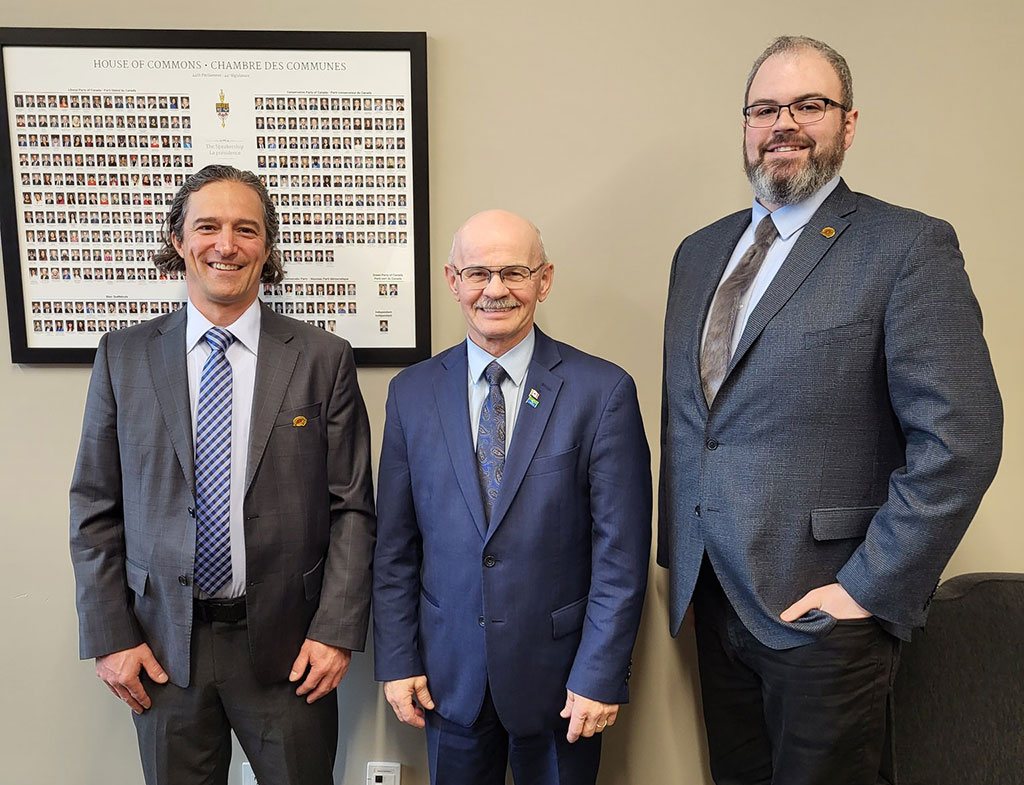

This year, three awards were presented: the Lloyd Cook Award, the Honorary Lifetime Membership Award, and the North American Furbearer Conservation Award.

Lloyd Cook Award

The Lloyd Cook Award was first presented by the FIC in 1993 in recognition of its namesake's commitment to excellence in trapping, trapper education and public understanding of wildlife management. Among the posts held by Lloyd in his lifetime were the presidency of the Canadian Trappers Federation and of the Ontario Trappers Association, forerunner of today's Ontario Fur Managers Federation.

This year's Lloyd Cook Award went to Robert Stitt, a valued member of the FIC for almost two decades. Robert was unable to attend the presentation, so the award was accepted on his behalf by Ryan Sealy, a conservation officer with the Government of Yukon.

Robert grew up in Ontario where he spent decades trapping and guiding hunters, before moving to Yukon in 2008. One of the first things he did on arriving was to join the Yukon Trappers Association (YTA), and, despite his enormous experience, signing up for the territory's Basic Trapper Education course. To this day, he is a director of the YTA, as well as being a past president.

For the past 15 years, Robert has run a trapline in a remote part of southeast Yukon, harvesting marten, beaver, wolf and wolverine. In most years, he offers upgrading workshops, particularly for marten and beaver pelt-handling and management, and also provides a mobile fur depot service in several communities.

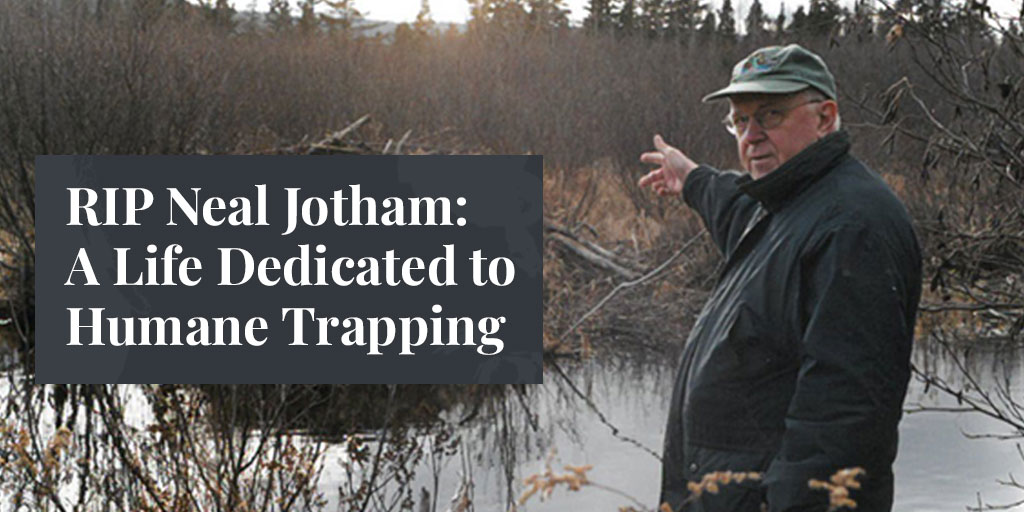

In 2011, Robert became a guest presenter for the Yukon Government's trapper education program, and in 2020 became an instructor. Students regularly comment on his close connection to the bush, his willingness to help new trappers, and his strong advocacy for humane trapping and good fur-handling.

Indeed, Robert's fur-handling skills are renowned, and the reason he has won many competitions. When teaching, he highly recommends his students read the Fur Harvesters Auction manual Pelt Handling for Profit.

Robert's other claims to fame are diverse. He is known as a presenter and writer, regaling audiences with inspirational tales of overcoming extreme challenges in the wilderness. He often writes letters to the editor on wildlife management issues, has published several stories about his life on the trapline, and is a regular contributor to Canadian Trapper magazine. And he is also a renowned moose-hunting guide, and a valued reporter on birds and other wildlife on his trapline.

Honorary Lifetime Membership Award

The FIC's Honorary Lifetime Membership Award celebrates people with long and distinguished track records of service to the fur trade, this year going to a man who has been involved with the institute from its inception, Yukon resident Harvey Jessup.

Harvey started his career in fish and wildlife management as a conservation officer, moving from enforcement to management in 1977 as a furbearer technician assisting with research on furbearer species such as marten, beaver, lynx, wolverine and wolves. This research led to the development of trapline management strategies for these key species. With the assistance of many Yukon trappers, the Yukon Trappers Association, the Manitoba Trappers Association, and the Canadian Trappers Federation, he developed a trapper education manual and training program for Yukon that is still in use today. He sat on the Western Canadian Fur Managers Committee which would later be incorporated into the Canadian Fur Managers Committee.

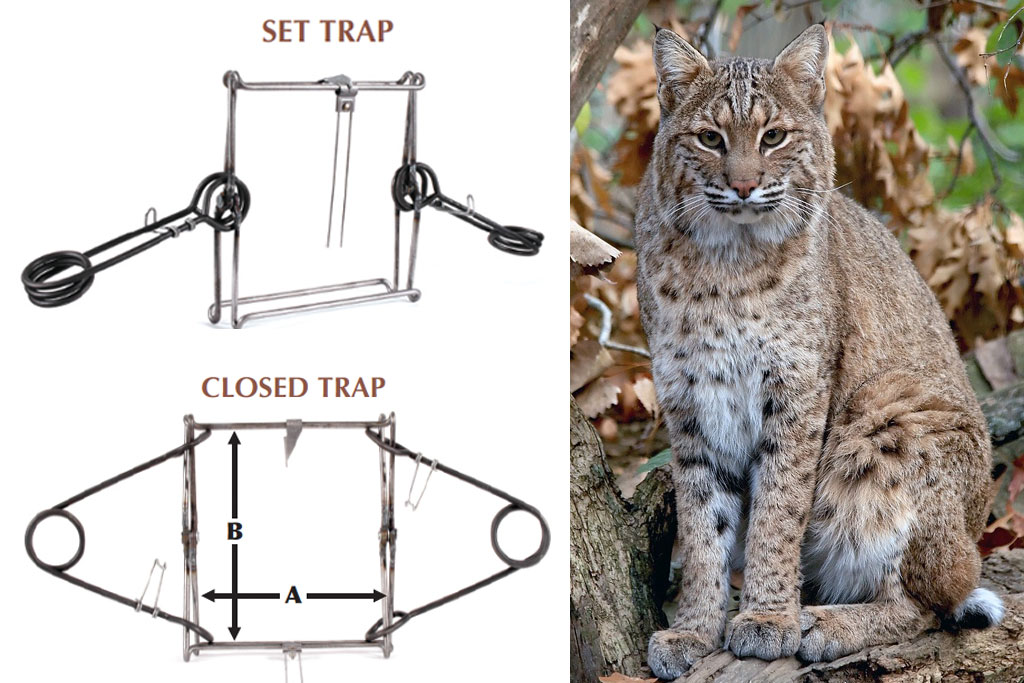

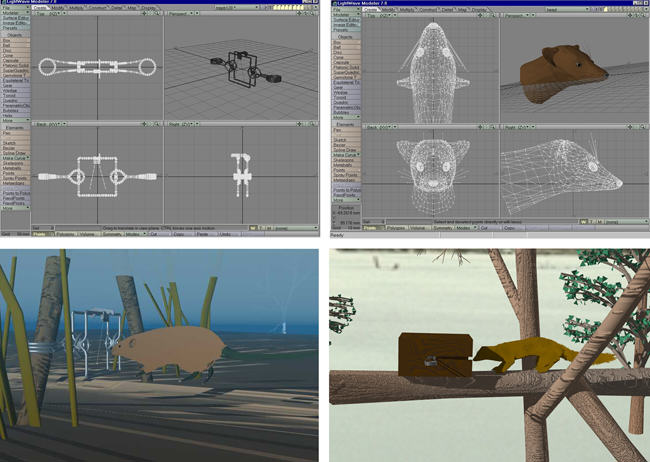

In 1982, Harvey became the fur harvest manager responsible for traplines, monitoring fur harvest and delivering trapper training. He continued as a member of the Canadian Fur Managers Committee. He attended the founding meeting of the FIC, was appointed to its first Board, and went on to serve for over 20 years. He held positions on the Executive and chaired the Trap Research and Development Committee for six years. He also participated on ISO191 through to the development of the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards.

His responsibilities with Environment Yukon expanded to include all wildlife harvest, managing licensed hunting, determining outfitter quotas and tracking harvest. He eventually became Director of the Fish and Wildlife Branch, before retiring in 2009.

In 2010, he was appointed to the Yukon Fish and Wildlife Management Board (YFWMB), a government advisory body established under Yukon First Nation Final Agreements, and served as chair for two years. Interestingly, the Director of Fish and Wildlife is identified in the Land Claim as the YFWMB's technical support, so Harvey has sat on both sides of the table so to speak!

In 2015 he was appointed to the Yukon Salmon Sub-Committee, a Land Claims advisory board on all matters pertaining to salmon in Yukon, again serving as chair for two years.

Throughout the latter part of his career and while sitting on the YFWMB, Harvey worked closely with Renewable Resources Councils, local government fish and wildlife advisory committees that have direct responsibilities for all matters pertaining to trapping.

North American Furbearer Conservation Award

The North American Furbearer Conservation Award aims to promote awareness and recognition of individuals and organisations that have made significant efforts in the field of sustainable furbearer management. This year's award went to Mike O’Brien from Nova Scotia.

On graduating from Acadia University with a master's degree in wildlife biology, Mike worked as a wildlife manager for the Department of Natural Resources and Renewables of the Government of Nova Scotia. He then became a consultant for many different wildlife management sectors, including the wild fur trade.

Mike has been an FIC Board member since 1998, serving first on the Trap Research and Development Committee, and currently as chair of the Communications Committee. He is also a member of the Executive Committee.

In his work for the FIC, Mike's forte is representing the institute at conferences involving diverse stakeholders and often contentious negotiations. These include the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the Convention on Biological Diversity, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species. He also works closely with other key stakeholders such as Environment and Climate Change Canada and the International Organization for Standardization.