HAPPY CANADA DAY 2020! On the first day of July each year, we celebrate the uniting of three British colonies – the Province of Canada, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick – into one federation, the Dominion of Canada, on July 1, 1867. It’s also a fine time to reflect on the unique role played by the fur trade in shaping our country.

Historians recall the role played by Europeans searching for fur in opening up our vast lands. But we should also remember that fur trading had been practiced here for hundreds, if not thousands of years before Europeans arrived.

When French navigator and explorer Jacques Cartier first visited the island of Montreal in 1535, he found Montagnais hunters from what is now northern Quebec already trading fur for food produced by Iroquoian farmers in the St-Lawrence valley.

Fur trading between First Nations and Europeans began when French fishermen came to exploit the vast stocks of codfish off Newfoundland and in the Gulf of St-Lawrence. When Cartier landed on the coast of northern New Brunswick, in 1534, he met Indigenous people who clearly had experience with Europeans, holding up fur pelts on sticks and eager to trade.

SEE ALSO: The country that fur built: Canada’s fur trade history. Truth About Fur.

In the five centuries that followed, Canada’s fur trade came to reflect the country’s cultural mosaic at its best: First Nations, French, English, Scots, Jews, Greeks and many others have worked together to build this remarkable heritage industry with its dynamic tradition of competition and cooperation.

But the fur trade is not just our history – it’s very much a part of modern Canada. More than 50,000 Canadians participate today in the many aspects of our industry, so let’s take this occasion to meet a few of today’s Fur Trappers, Farmers, First Nations, Manufacturers, Designers, and Retail Furriers.

Dan Kahnert – The Industry’s Link with Consumers

(Click here for an expanded version of this interview.)

Like so many in the industry, Dan Kahnert’s relationship with fur is a family affair.

“My great-grandfather learned the fur trade in Germany and came to Canada in the late 1800s. His son, my grandfather, moved to Toronto where he would travel around taking orders, and then cut and sew coats in his home. It was my father, Allan, who opened our first showroom on Avenue Road in 1957, where Kahnert’s is still located.

“I would help out at the store on weekends, and decided by the end of high school that I wanted to join the family business. That’s what I did in 1984, after completing my degree in economics and business at the University of Western Ontario. I arrived home with all my college furniture and everything on April 30 and began working full-time in the store the next day; it was storage season and there was no time for a break!

“We worked hard, six days a week, but I enjoyed the challenges of running a business, being our own bosses, analysing problems and implementing a plan. My older brothers, Bernie and John, were already working at the store with my father, and John and I still run the business together today. It really helped that dad was very open to letting us try new ideas, like when I brought in computers in the 1990s.”

What does Dan like best about being a retail furrier?

“In addition to working with my brother and running our own business, what I enjoy most is the opportunity to meet lots of new people. While not every customer is easy, as everyone working in retail knows, generally we meet lots of very nice people. When we say, ‘It’s been a pleasure doing business with you,’ it’s not just a cliché, it really is how we feel.”

We are on the front line with consumers, and we are proud to do our part to promote fur on behalf of all the people who make up this uniquely Canadian heritage industry!

And how has the business changed over the years?

“There’s no way around it, aggressive animal rights campaigning has hurt us. Most people still love fur, but the activists have made them feel nervous about wearing it. Some of these intimidation campaigns are really a form of violence against women, which is very sad,” says Dan.

“Unfortunately, we have difficulty getting across our messages about the real environmental advantages of wearing fur. Fur is a sustainably produced, long-lasting, recyclable and biodegradable natural material. Animal activists have created very damaging confusion about the real environmental issues. It makes no sense telling people to use petroleum-based synthetics instead of long-lasting natural and biodegradable materials. The saddest thing is that most consumers we speak with do appreciate the warmth, comfort and beauty of natural fur, but they feel intimidated.

“We have adapted, of course: we will sell our customer a shearling coat – because, ironically, shearling is not seen as fur. Or a fur-lined coat. We have also added cashmere and other cloth coats, with or without fur trim. Not because there’s anything wrong with fur, but because fur has been tangled up in a very complex societal discussion about using animals, which includes everything from medical research to circuses to eating meat. Fur, unfortunately, has become a scapegoat, because we are really a very small-scale industry; we don’t have the financial or professional clout that large corporations can muster to tell their story when they are attacked.”

And the future?

“I don’t think fur will ever really go out of style, because it is so in tune with growing environmental concerns. We have to keep working on telling that story, but ultimately it is up to the consumer to make an educated decision on the benefits of buying fur products ” says Dan.

“But, bottom line, as a retailer your success depends on satisfying your customer. We are located in a wonderful residential neighbourhood and therefore do not rely on tourist sales that might occur in downtown Toronto. We rely on community word of mouth with support from our online business. We have one of the city’s best collections of high-quality coats, and we work hard to take good care of every customer. We are on the front line with consumers, and we are proud to do our part to promote fur on behalf of all the people who make up this uniquely Canadian heritage industry!”

SEE ALSO: Fur retail: The art and science of making sales. Truth About Fur.

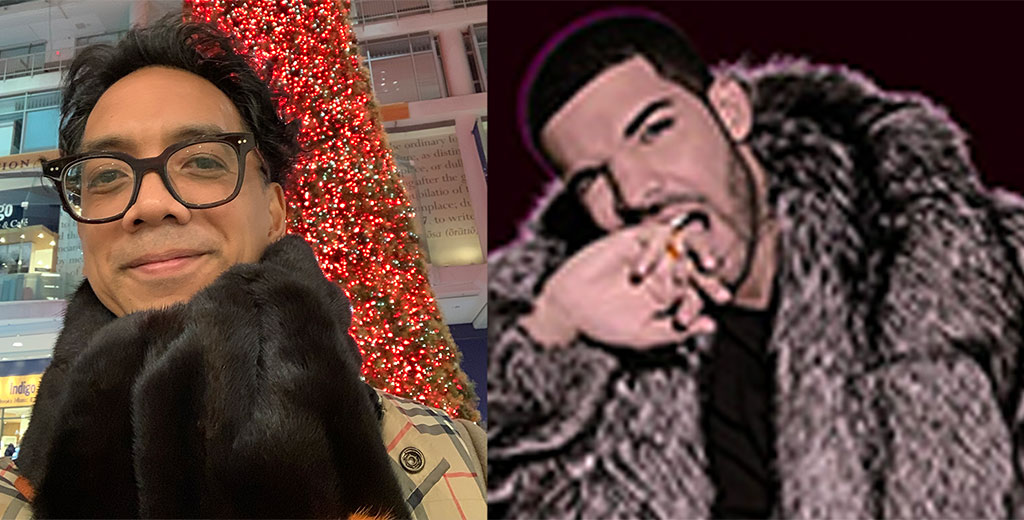

Farley Chatto – Stylist to the Stars

If you’ve never heard of Farley Chatto, then you’re probably not in tune with fashion, and couture in particular. But if you love couture and Canadian design, Farley is probably a household name. Not only is he an internationally recognized designer, he is also a stylist for celebrities. He consults with Hollywood A-list hit TV shows and movies, including Suits, Christmas Chronicles, American Gods and more. As a Toronto resident, he is proud of his Canadian roots.

Farley’s love for fur began in his childhood. In winter, his father would pick him up from school wearing a muskrat-lined Royal Canadian Mounted Police hat. He remembers touching it and loving how soft it was, and thus began his love affair with fur. As he grew up in the 1980s, the fur was a staple as a must-have luxury item on TV shows.

“In the 1980s, Dynasty was a top-rated show depicting the lives of the rich and powerful, where fur and excessive fashion were a big part of the show’s popularity,” he recalls. “Then, one day, I asked my mother if I could have a sheared beaver bomber jacket for winter. Sadly I didn’t get the coat, yet I was hooked on the tactility of fur!”

People forget that this country exists because of fur. Fur is the fabric that bundled our nation together.

Farley continues to be proud that fur is as Canadian as apple pie is to Americans. Because fur is a staple in the fashion industry, he was anxious to incorporate it into his designs when he entered the field.

“Being a Canadian designer can be challenging,” he says. “I’ve been on the scene for 32 years, and the beginning wasn’t easy. I applied and was accepted to three fashion schools here and in the US, yet I decided to remain true to my roots and stay here. People forget that this country exists because of fur. Fur is the fabric that bundled our nation together.”

When asked on advice for young designers with interest in fur, Farley’s motto is: “If you have an opportunity, take it! Sign up for courses, join workshops, learn with First Nations people, put yourself out there.”

Wherever Farley travels, whether to teach or research, he touts the sustainability of fur fashion to others. As he says, it’s #furtastic.

Shawna Ujaralaaq Dias – Traditional Fur-Trimmed Parkas with a Modern Twist

As a child, Shawna lived for several years in a tiny settlement in Wager Bay, above the Arctic Circle on the extreme northwest coast of Hudson’s Bay.

“My grandfather had run the Hudson’s Bay post that was built there in 1925; there were only 15 people when my parents were living there, all family,” she says. “They would take the dog team to visit with other families nearby.

“It was a great life. My father hunted and trapped – foxes and wolves — and we were always outdoors, active and healthy – not like the kids who sit in front of computer screens these days!

“We kids would help to clean and scrape skins, and I began sewing by the time I was seven. I was using a sewing machine soon after that.”

The family moved about 300 kilometres south to Rankin Inlet, a small town (population 2,800, in 2016), so Shawna could attend school, but returned to their camp in Wager Bay each summer to hunt, fish and reconnect with the land.

“I didn’t even speak English until we moved to Rankin,” says Shawna. “We spoke Inuktitut, and I was lucky to learn all the traditional ways. These are the traditions I celebrate in my sewing.”

Now married with three grown children (18, 21 and 24) and a government job, Shawna never stopped sewing, and about ten years ago started her own business.

There is so much skill and creativity in the communities, and now with the Internet we have access to the world!

“People would see my fur-trimmed parkas and ask if I could make them one. Now I show new parkas on my Facebook page, and they are usually sold within 48 hours. Even though we live in a remote community, the Internet puts us into contact with customers across Canada and even in the US or beyond!”

Shawna now has more than 6,000 Facebook followers, and in 2017 she began selling dressed fur pelts, in addition to parkas.

“A lot of the ladies in small northern communities are sewers, but they often have difficulty finding fur pelts to work with. They really appreciate being able to get dressed furs from me up here.

“I like to promote the work of other ladies too,” said Shawna. “There is so much skill and creativity in the communities, and now with the Internet we have access to the world!”

So: with a government job and a growing sewing business, does Shawna still have time to connect with the land?

“For sure, we still go out to our hunting camp most weekends, and every summer. My husband only came north about 20 years ago, but he learned many hunting and trapping skills from my dad, and he loves the life here. My boys also hunt caribou and seals. We have a good life, and I am happy to be able to share some of the beauty of our Inuit culture with my sewing.”

Christina Nacos – Re-inventing Fur for the Next Generation

Some people are born into the fur industry, some people choose it. For Christina Nacos, it was both.

Her father, Tom Nacos, is a legend of the Canadian fur industry. After learning the trade in his native village of Siatista, in the mountains of northern Greece, he emigrated to Montreal in the 1950s and proceeded to build one of North America’s most important fur manufacturing and retailing empires.

Christina crossed the ocean in the opposite direction, living in England for several years, where she worked in advertising. She returned to Canada in 1998 to work with Natural Furs, one of her father’s companies, and as one of the younger people leading a major company in the industry – and one of the very few women – she quickly began exploring ways to adapt fur for young people like herself.

“I think that each generation learns from their predecessors, but then has to make the industry their own, adapting fur for their time. That’s how fur has always evolved,” she says.

Under Christina’s leadership, Natural Furs was one of the first companies to participate actively in FurWorks Canada, an innovative project coordinated by the Fur Council of Canada to modernize fur fashion, mixing fur with other materials for a sportier look that reflected more modern, active lifestyles. Natural Furs was also a strong supporter of the Fur Council’s “Beautifully Canadian” collective branding initiative.

Christina is a strong believer in the important role of industry associations, especially in a sector made up of hundreds of small family businesses; she has served as vice-president of the Fur Council for many years.

As society thinks more deeply about the challenge of shifting to a more sustainable economy, fur will make more sense than ever.

Christina’s latest project to bring fur fashion into the 21st century is a major push to promote recycled – or “upcycled” – fur, to make fur more accessible and avoid waste. Branded as FURB Upcycled, the collection is attracting younger women who may never have worn fur before.

“We noticed that many young people were attracted by the nostalgia of remodelling furs they had inherited from their parents or grandparents. It’s a way to reconnect with the past, and it’s totally in synch with current efforts to prevent waste and use sustainable materials. Often we’re using the fur inside the garment, to maximize its warmth and functionality. We’re mixing upcycled fur with other materials, and exploring a more laid back, Scandinavian aesthetic.

“My sister-in-law, Sarah Nacos, has now joined me in the company. She’s 28, and brings the sensibility of an even younger generation of women to our designs,” she says.

“Each generation brings something new to fur. Young women today love the echo of the past in an upcycled piece, and they appreciate the durability of fur, which prevents waste – all important sustainability virtues.

“As society thinks more deeply about the challenge of shifting to a more sustainable economy, fur will make more sense than ever,” she says.

So Christina Nacos is continuing a family tradition in the best possible way: by totally rethinking how fur can be adapted for the next generation.

Robert Grandjambe – Deeply Connected to the Land

Robert Grandjambe Jr. is a Woodland Cree from Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories, whose roots go back to Fort Chipewyan, Alberta, where generations of his family trapped to survive. For many southerners, and city dwellers in particular, his deep connection to the land may seem like a dream lifestyle, and sometimes even hard to understand, so it helps that he is committed to explaining it to anyone who will listen.

Trapping is a perfect example. “I think people need to better understand the importance of what trappers do, because I don’t think they get it,” he says. “We must educate people to understand that everything the trapper does contributes to a natural and sustainable way of life and the environment, and is crucial for the culture and health of our communities.”

Robert started learning trapping from his father when he was six years old, and now he’s determined to pass on everything he’s learned. Out of trapping season, when he’s not working as a contractor, he does presentations in schools about culture, craft-making, hunting and gathering, and of course trapping. Also receiving a solid grounding in what it means to live on the land is his toddler daughter.

“As a father you want to leave a legacy,” he says. “I want to give her all my knowledge and experience from the trapline, and from there she can choose her own path. So I will continue to bring her into this world, so she can understand and know it well.”

Among the lessons that Robert passes on is the importance of supporting your community at large, and for him this means providing food – as much as he can, be it moose, ducks, bison, bear, geese, or any of the other wild bounty the land provides. He views food as “the thing that brings us all together at the same table and sustains us, no matter who we are or where we come from.”

We always ask ourselves, how can we do it better when it comes to animal treatment?

As for trapping, one important aspect that is close to Robert’s heart – as it is for most trappers – is animal welfare. In part this might be because his great-great-grandfather trapped in the early 1900s alongside Frank Conibear, one of the founders of the humane trapping movement, who in turn learned much about respecting animals by working alongside Indigenous people.

Robert is adamant that concern over animal welfare is not a recent development forced on trappers by the animal rights movement. “We always ask ourselves, how can we do it better when it comes to animal treatment?” he says. “The standards have improved dramatically over the years and we still strive to keep improving. As trappers, we always focus on only taking what we need, and making sure we respect the animals and the environment.”

As for the future of wild fur, Robert has a positive outlook, despite the many challenges facing trappers. He may not have all the answers yet, but he’s confident the pieces are all there to make it happen.

“I truly believe trappers and wild fur will always have a place in this world,” he says. “We needed it once just to survive, but today it is about much more than that: It’s about social and cultural values, family values, our health and well-being, and protecting nature, ecosystems and the environment.”

SEE ALSO: “Trapping is beautiful” says proud Cree Robert Grandjambe. Truth About Fur.

SEE ALSO: Letter from a Cree trapper: Nature is our refuge from Covid-19. Truth About Fur.

D’Arcy Moses – First Nations Heritage Inspires Modern Fur Designs

(Click here for an expanded version of this interview.)

If you are looking for a designer who incarnates the Canadian fur trade’s rich cultural mosaic, D’Arcy Moses is an obvious choice. Adopted at birth and raised by a non-native farming family in Camrose, Alberta, D’Arcy set out to connect with his aboriginal roots after he left home. While his background sometimes left him feeling uncomfortable (“like an apple, red on the outside, white inside”), in Vancouver he met Leonard George, chief of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, who assured him he could have the best of both worlds. “He told me, ‘You have the First Nations culture and you have the non-aboriginal culture. You can utilize that, because you can mix between cultures at ease.’”

D’Arcy’s chance to apply his unusual heritage to designing clothing came at the Toronto Fashion Incubator, and in 1991 his work was featured at the Toronto Festival of Fashion. Then he was invited to Montreal by the Fur Council of Canada, and began working with one of the country’s most important luxury apparel manufacturers, Natural Furs.

The unique, aboriginally inspired collections D’Arcy developed went to high-end retailers in North America, Europe and Asia, and a retrospective collection of his work was recently added by the Government of the Northwest Territories to its permanent collection of Indigenous arts and crafts.

Progressives who want to ban fur need to look at the whole ecosystem, the broader impact of industries, not just the individual animal.

Then in 1996 his life took another unusual turn. After CBC aired a documentary about him, he received a call from the Pehdzeh Ki First Nation, in Wrigley, NWT. Moses is a common family name there, and they had been looking for him. So D’Arcy left the glamour and hectic pace of international fashion to settle in the home he had never known. His business experience landed him a government job, but sewing and designing were never far from his mind.

Twelve years later he had saved the funds needed for his current project: a workshop in Enterprise, NWT, a community even smaller and more remote than Wrigley. “I needed somewhere I wouldn’t be distracted from my design work,” he says.

And the work has been abundant and diverse. In January, D’Arcy participated in a residency at the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and he will return to Banff to lead a workshop for Indigenous design students from around the world. “We will be using traditional techniques to re-purpose fur, leather and other natural materials,” he says.

“Many people in my community still hunt and trap, and their attachment to the land is very strong. But natural materials like fur are also important at a time when people are increasingly concerned about protecting our natural environment. So-called ‘fast fashion’ is killing the Earth.

“Progressives who want to ban fur need to look at the whole ecosystem, the broader impact of industries, not just the individual animal. When we look at the whole picture, from sourcing to use and maintenance, through to disposal, it is clear that we should be using responsibly and sustainably sourced natural materials – wool, leather, fur. The First Nations understood that we are part of nature and that we have an obligation to use resources with respect. I hope that my designs, marrying traditional and modern themes, can help people remember these important lessons,” says D’Arcy.

SEE ALSO: D’arcy Moses’ big bet. Up Here, October 2015.

Tom McLellan – Mink Farming Maintains Proud Rural Heritage

Tom McLellan, a third-generation mink farmer from Ontario, feels tremendous pride when he speaks of his family’s history and their contribution to the early agricultural economy in Canada. “It is comforting to know that my family has been a part of what helped shape Canada into the nation that it is today,” he says.

“My father and his father before him loved working with animals and, being a part of Canada’s agricultural development just made the work even more satisfying. Now my sons are learning about fur and our connection to the birth of our great nation. It’s a wonderful feeling,” he says.

We are always studying the science behind mink farming to improve the health of our animals and make them comfortable and happy.

The early days of the fur trade focused on trapping, and the beaver pelt was the motor of the economy. By the end of the 19th century, Canadians were pioneering fur farming as the way to produce uniform, high-quality pelts without overexploiting wild populations. Over time, farmed mink became the most popular fur for consumers who appreciated the warmth and luxury.

“Improving the quality of the fur and keeping our animals healthy is what keeps us going on a daily basis,” says Tom. “We are always studying the science behind mink farming to improve the health of our animals and make them comfortable and happy.”

Canadian mink farmers are proud to produce some of the finest furs in the world, and also of their commitment to animal welfare. They follow codes of practice developed by the National Farm Animal Care Council, and their farms are certified by independent auditors. This Canadian heritage industry is proud of its past and, equally important, is well positioned to continue supporting rural communities.

SEE ALSO: Facts about fur farming. Truth About Fur.

Joe Williams – Continuing a Family Tradition

What makes someone get up early each morning and put in long days on the farm?

“We are proud of the care we provide for our animals,” says Joe Williams who, with his two brothers, runs two mink farms in the lower mainland of British Columbia.

“It’s a family tradition, and fur is part of Canada’s heritage,” says Joe.

“Canadians pioneered the farm raising of furbearing animals, foxes on Prince Edward Island and mink in Ontario, and we are proud to be part of that heritage.

“My father started his first farm in 1990, and I would help him on weekends and after school,” he recalls.

“For sure it’s lots of hard work, but it’s rewarding. I like working for myself and being outdoors and caring for the animals. There’s a satisfaction in following the full cycle with the animals, from breeding season, to whelping and ensuring the pups are healthy, right through to the final product.

“I am also lucky to be working with my brothers,” says Joe.

What would he like people to know about mink farming?

“I would like people to understand how hard we work to keep our mink healthy and content. Every day we are adjusting their care and nutrition, depending on the time of year and their growth cycle. The proportion of proteins and fats and other elements are adjusted depending on whether the mink are being prepared for mating or whelping or growth. We are learning all the time.

“And then we are maintaining pens and barns and equipment; mixing feed; planning genetics for the next mating season, working to improve our herd.

“There’s a lot more that goes into this than most people understand. And, honestly, if you don’t care about the health and welfare of the mink, you really can’t do a good job; it will show in the quality of the fur you produce.”

Fur makes more sense than ever in our eco-conscious times!

And what would Joe say to a consumer considering the purchase of fur apparel or accessories?

“I would like consumers to know that fur is produced responsibly and sustainably. Mink are carnivores; they are fed left-overs from our food production system, the parts of chickens, pigs, fish and other animals we don’t eat and would otherwise end up in landfills.

“We basically recycle those ‘wastes’ by feeding mink to produce a warm, beautiful and long-lasting natural clothing material,” says Joe.

“At a time when we are all looking for ways to ensure that our lifestyle choices are helping to protect nature for future generations, I would like consumers to know they can wear fur with pride. Fur is an important part of our Canadian and North American heritage. And fur makes more sense than ever in our eco-conscious times!”

SEE ALSO: A year on a mink farm. Truth About Fur.

Katie Ball – Trapper, Designer and Advocate

When Katie Ball is not out on the land in Thunder Bay, Ontario, she’s either designing and making fur garments at her own Silver Cedar Studio, or she’s advocating for the fur trade on behalf of the Northwestern Fur Trappers Association, the Ontario Fur Managers Federation, the Northwestern Ontario Sportsmen’s Alliance, and Fur Harvesters Auction. Only a person with fur coursing through her veins could build such a résumé!

“The love of Canada and our national heritage is nowhere better reflected than in the fur trade,” says Katie. “For me to be a part of this incredible industry is beyond humbling. Spending time out in the wilderness and being at one with Mother Nature and learning from my father is where my pride begins.

“I know that we are using the most humane methods possible, and respecting the delicate balance of nature to ensure viable populations for years to come. So I take pride in carrying on my family traditions, while playing the role as a steward of the land. There is no better way to spend one’s time than with family, doing what you love.”

Katie then takes this a step further, turning raw pelts into stunning fur garments.

“For me to be able to take this passion and turn it into a creative, fashionable yet functional wild fur product to be enjoyed for generations to come, is also a gift I hold dear,” she says. “Nature and the fur trade itself have been major influences in my daily life that allow me to translate them into usable pieces of art and heritage. Being able to express myself through my creations has allowed me to grow as an individual.”

Standing side by side with some of the most respected people in our industry that I call family and friends, is what lets me know I am where I belong.

“However, true pride shines brightest within the fur community if you ask me. The camaraderie between trappers and their families is unrivalled. The way we share our knowledge with one another, as well as the willingness to help educate newcomers, strengthens our friendships and grows our community as a whole. Trappers and their families are a closely knit community no matter where you go. There are always friendly smiles and stories to be heard.”

Completing the picture, as it were, of a lady who lives and breathes fur, is Katie’s involvement in advocacy.

“Finally, knowing that I have the backing from my local trappers council, as well as the Ontario trappers, is where my creativity, passion and strength come together. Helping fight for the rights of trappers, all the while educating the public about why the fur trade is so important to Canadians. Standing side by side with some of the most respected people in our industry that I call family and friends, is what lets me know I am where I belong.

“So be it on the trapline, in the studio, or at a board meeting, I know that what I do and love makes a difference. By being a part of this vast community and historical trade, with so much more to be shared and done in the near future, I cannot wait to see where we as a whole will take it.

“This is how we grow as a community, and these are just a few of the many reasons why I am proud to be a trapper.”

SEE ALSO: “Fur is in my blood” says Katie Ball, trapper, designer, advocate. Truth About Fur.

Robin Horwath – Trappers Are “Great Stewards of the Land”

Hailing from Blind River, Ontario, Robin Horwath started helping his father on the trapline at the age of 12. In so doing, he became the next torchbearer of a family tradition that dates back to both his grandfathers.

“As we go through life, it is not always clear at the time what or who influenced us along the way,” he says. “When my Grandpa Temple died at the age of 99, I saw a photo of him in an album for the first time. It was taken in 1928, and shows skunks and muskrats hanging on a shed, all skinned, boarded and ready to sell. Today, that photo is on my desk at work.

“When I was still nine or ten, I remember both him and my Grandpa Horwath telling me that they both had trapped skunks and muskrats. At the start of the Great Depression, they were paid $3 a muskrat and $5 a skunk. When I saw the picture of Grandpa Temple, it brought back all the stories they had told me as a child.

“My father was a great influence also, as he taught me to hunt, trap and fish as I grew up, and learn our family’s traditions and values.

“So I am proud to have carried on my family’s way of life. I have followed in the footsteps of my grandfathers and father, joined by my brother and my son. And hopefully my two young grandsons will want to do the same in the future.”

Aside from the personal pride Robin has in continuing his family’s heritage, he’s also committed to serving others in the trade. Today he is both general manager for the Ontario Fur Managers Federation and a board member of the Fur Institute of Canada. So what path did he follow to reach this point?

“After studying in Iron Bridge under trapping instructor Walter Tonelli, I got my first trapping license in 1981 to help my father on his registered trapline, and I’ve held one ever since. In 1995 I became a director for the Blind River Trappers Council, and in 1996 I studied to be a trapping instructor in Thunder Bay as part of a program run by the Ontario Fur Managers Federation and the Ministry of Natural Resources. And by 2010, I was the OFMF’s general manager!”

If you are a trapper, don’t be afraid to introduce someone new to what and why we trap. And if you are not a trapper, take the opportunity to ask if you can tag along.

So what motivates him to give so much of his time in the service of others?

“I am very proud to be a part of Canada’s fur trade,” he explains, “and I have had great opportunities in my life to be able to help promote, educate and train people in its traditions and heritage. It is amazing when you think that the Hudson’s Bay Company received its royal charter in 1670 – so 2020 is the HBC’s 350th anniversary, making it one of the longest-running corporations in the world. Trapping is what drove the exploration and development of this great land we call Canada.

“I never thought when I started trapping that I would end up representing trappers provincially and nationally on behalf of the OFMF and the Fur Institute. It’s a great privilege.”

So what advice does he have for others looking to get involved in promoting the fur trade?

“I dream of the day when trappers once again are recognized and valued by the general public as great stewards of the land. Trapping is a vital tool for managing furbearers to achieve healthy sustainable populations, to protect infrastructure, and control the spread of disease, which is important not just for the animals but also for humans.

“So if you are a trapper, don’t be afraid to introduce someone new to what and why we trap. And if you are not a trapper, take the opportunity to ask if you can tag along to see what it is all about for yourself, so you can make your own informed opinion on why trapping needs to continue.”

SEE ALSO: In their own words: Fur trappers on Ontario’s oldest profession. TVO.org.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.