Canada-EU Summit: Chance Missed to Review Seal Ban, but Not Lost

by Doug Chiasson, Executive Director, Fur Institute of CanadaOn Nov. 23-24, all the right people – leaders from the European Union and Canada – were gathered in St….

Read More

On Nov. 23-24, all the right people – leaders from the European Union and Canada – were gathered in St….

Read More

On Nov. 23-24, all the right people – leaders from the European Union and Canada – were gathered in St. John’s for the Canada-EU Summit. Those of us representing Canadians who make their livings in remote and rural areas from Prince Rupert to Newfoundland’s outports, by harvesting fur and seals, were hopeful. Meetings such as these provide high-level government representatives with an opportunity to discuss issues that matter to their respective governments behind closed doors and far removed from everyday citizens.

And, this summit was different. Instead of being monitored only by political gadflies and lobbyists, people in remote communities across Eastern and Northern Canada watched closely. They watched because the summit was held in Newfoundland, where the ocean and its bounties have long been the bedrock of the economy and culture.

This, of course, is the same St. John’s that once was home port to steamers, which brought hundreds of Newfoundlanders to the ice of the North Atlantic to harvest seals. The same St. John’s where European celebrities descended to hold press conferences in front of TV cameras to attack the livelihoods of hunters who put their lives on the line on the ice to provide for their families. The same St. John’s where, for over 30 years, the elected officials of the provincial government sat on sealskin chairs as they debated the business of the day.

In 2009, the predecessors of those same EU officials who were fêted in St. John’s banned the trade of Canadian seal products, striking a blow to rural communities across Eastern and Northern Canada that had relied on the hunting of seals for hundreds of years. Regulation No 1007/2009 inflicted untold damage not only to communities in Newfoundland and Labrador and Quebec, but also to Inuit communities across Canada’s North.

The impact on Inuit communities was the genesis of a challenge to the ban in the European Court of Justice, brought by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami and supported by the Fur Institute of Canada and others. This was followed by a challenge by the Government of Canada at the World Trade Organization. Though it upheld the ban, the WTO challenge forced the EU to allow an exemption for seals harvested by “Inuit and other Indigenous communities”.

This is the exemption that European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said was “working well” and that a “good balance” had been found on seals. This is completely and unambiguously false. Only two bodies in Canada are recognized as being able to certify that a seal product comes from an Indigenous harvest: the Government of Nunavut and the Government of Northwest Territories. In a report from her own Commission, it shows that Nunavut has only exported two sealskins to Europe, in 2020, and the Northwest Territories exported just two sealskin coats, in 2022.

Perhaps even more revealingly, that same report contains four EU member states saying that the ban’s “impact has gone beyond its intended purpose”. These four states – Estonia, Latvia, Finland and Sweden – all still have their own seal hunts but are hamstrung the same way Canadian sealers are when it comes to trading their products.

In terms which would be shockingly familiar to anyone on Canada’s East Coast, these states raise concerns about the impacts of seals eating cod and salmon, about infecting fish with parasites, and impacts on commercial and recreational fisheries.

Unfortunately, EU and Canadian officials did not avail themselves of an ideal opportunity to reverse the historic injustice of the 2009 seal ban when they gathered in St. John’s.

But it’s not too late. The European Commission is launching a review of the Regulation on Trade in Seal Products in 2024. Canada can, should, and must work closely with the EU member states that are unhappy with the ban, supported by Canada’s sealing industry and Indigenous leadership, to overturn the regulation.

We also need European Commission leadership to engage honestly and candidly on the damage done by this ban and chart a course to move beyond the mistakes of the past. This conversation must be elevated to the most senior levels and involve representatives of the industry and Indigenous communities directly impacted, not the extremist animal-activist groups whose goal is to destroy the way of life of people who live close to the land – and sea – and who use renewable natural resources responsibly and sustainably..

Shared adversity can bring out the best in people, and that’s the silver lining to the very dark cloud that…

Read More

Shared adversity can bring out the best in people, and that's the silver lining to the very dark cloud that is the Covid-19 pandemic. Around the world, people are helping others any which way they can, from singing opera on Italian balconies to simple acts of kindness like delivering groceries to the elderly or cleaning restrooms for truckers. So while it does not surprise us, we are proud that the fur trade is also doing its part.

Countless efforts are being made in ways we'll never even hear about, but here are a few that have come across our desk. If you know of other efforts from the fur trade that we can add, please drop us a line at [email protected].

SEE ALSO: Letter from a Cree trapper: Nature is our refuge from Covid-19. Truth About Fur.

It's no wonder that New York's fur trade has been stepping up. The city and state have been the North American epicentre of the pandemic, non-essential businesses have been shuttered, and hospitals have faced a desperate shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE).

So playing to their strengths, local furriers have been turning their hands to making masks and hospital gowns. In early April, an order was secured to provide 50,000 units to several Brooklyn hospitals, with the certainty of more to follow, and all costs to be covered by the city or state. "This opportunity allows us to perform a tremendous service for our first responders and healthcare workers on the frontline," said an industry appeal to its members, urging others to join. "It also puts our people back to work during an economically trying time with no immediate end in sight."

One company now busy making masks is Tres Chic Furs in the city's Garment District. Owner Golfo Karageorgos would prefer to be making medical-grade masks, but the fabric has been hard to find, she told the New York Post. Let's hope that situation changes, but for now her six employees are producing commercial-grade, three-ply, non-woven disposable masks, and giving them to everyone from corrections officers and supermarket workers to hospital staff. “We’re producing tens of thousands of these and giving them out as we’re making them, literally, as people need them,” she said.

“The coronavirus has shown how important local, small manufacturers are given the crisis we’re enduring right now and how broken our supply chain is,” she said. “The city tried to ban the fur industry last year, and we fought them, saying that we’re local small business owners and manufacturers and we're the foundation of the city and what it’s built on. And if anything, this pandemic has shown how important local manufacturing and small business is."

The Post also reported that trade group FurNYC purchased and provided 5,000 KN95 masks (certified by the Centers for Disease Control) to City Councilman Robert Cornegy to donate to two hospitals in his district.

“I’m pleased to work with the fur industry on this initiative, to manufacture masks for people and secure KN95 masks for people on the front lines in hospitals," said Cornegy. “This is an opportunity for two forces, a politician and a unique industry, to help serve the people of New York. We should all be able to come together in crisis to do good for our city.”

Meanwhile, in the Chicago suburb of Westchester, Christos Furs has begun making two types of mask. Simple MERV 13 masks will serve the public well, or if you want a mask to "last you a lifetime", check out its double leather and double MERV 13 masks with interchangeable filters.

SEE ALSO: New priorities? Fur in a time of coronavirus. Truth About Fur.

Small and large, Canadian companies are playing their part, and that includes the largest player in the fur garment industry. Since late March, Canada Goose has been steadily expanding its production of PPE, with the aim of getting all eight of its manufacturing facilities - with some 900 employees - operating at capacity. In an Apr. 9 press release, Canada Goose said it was producing at least 60,000 gowns and scrubs per week, with contracts to produce 1.5 million L2 gowns for the federal government, and 100,000 reusable gowns for Shared Health Manitoba.

“With one of the largest Canadian apparel manufacturing infrastructures in the country, we are uniquely positioned to re-tool our facilities and refocus our teams to produce a variety of personal protective equipment," said president and CEO Dani Reiss. "And we are prepared to leverage all of our resources to do what’s right for our country."

For sure there are others in the fur trade helping fight Covid-19, but until we hear about them, let's close with a couple of special mentions.

The International Fur Federation has stepped up to help others in the trade contribute to their communities. Cash awards have been dispensed in Ontario, New York, Romania, Turkey, Italy, and Kastoria, Greece, to help fund medical equipment including PPE. In Ontario, the funds have been coursed through Fur Harvesters Auction for use by the North Bay Regional Health Centre Foundation. "At this awful time it’s important the fur trade does its part to support communities," said IFF CEO Mark Oaten.

SEE ALSO: The fashion and fur industry fight back against the Covid-19 virus. International Fur Federation.

And last but definitely not least, we have Dave Hastings, president of the trapping association Fur Takers of America. Dave will be surprised by this accolade, but it's really for the millions of people like him who are keeping society ticking over by providing vital services.

It started with an innocent question from me, never intending to put Dave on the spot! Did the FTA have any plans as an association to help fight Covid-19? Dave responded with frustration and embarrassment, but a sense of resignation that since most trappers live in rural areas, organizing initiatives can be challenging. "We have several ideas cooking though," he said, determined to stay upbeat.

Dave hails from a small community of perhaps 100 people, he explained. "My neighbors are elderly and immune-compromised. We, all the close neighbours, pitch in - scoop the walks, pull the trash containers out on trash days, pick up items at the stores, help with transportation, carry the mail to houses."

"So the members of our community are pretty engaged, much as they would be everywhere I hope," he continued. "Lots of mask-sewing going on all over. Red Cross blood drives - even under the cloud of Covid risk, we are still gathering much-needed blood for our hospitals."

Well, that sounds great, I thought. And then came the icing on the cake!

"I'm a volunteer on the local Fire/Rescue team. Our protocols about emergency response are a little intimidating under the circumstances, but we still definitely respond to ambulance-assist calls, car accidents, fires, just about any 911-related need. Not a man or woman on the crew has asked to step down."

So it's hats off to everyone in the trade busy making PPE! And it's hats off also to everyone helping in other ways! You may not have a sewing machine or be a fireman, but we can all help in the fight against Covid-19. And remember, if you know of someone in our trade who's answered the call to arms, please let us know at [email protected].

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

The remarkable tale of one man’s experiment in domestication is told in How to Tame a Fox (And Build a…

Read More

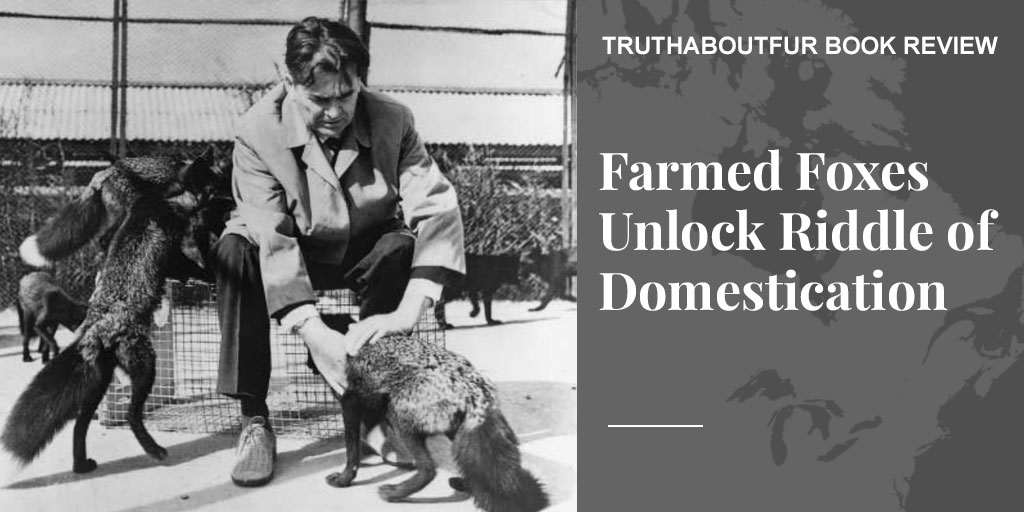

The remarkable tale of one man's experiment in domestication is told in How to Tame a Fox (And Build a Dog) [University of Chicago Press, 2017], by Lee Alan Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut. Photo: Institute of Cytology and Genetics archives.

In the Fall of 1952, a Russian scientist boarded an overnight train from Moscow to Tallinn, the capital of Soviet Estonia. It was the beginning of a remarkable adventure that would change our understanding of animal domestication.

Dmitri Belyaev, a geneticist by training, was a lead scientist at the Central Research Laboratory on Fur Breeding Animals in Moscow, working to help the many government-run fox and mink farms produce more beautiful and valuable furs. Fur farming was an important source of foreign currency for the Soviet government after the war, which provided Belyaev with some protection for the daring experiment he was about to launch.

It was protection he needed, because while Russian geneticists had once been world-leaders, this important new field of study was under attack in Stalin’s Russia. Soviet science policy was dominated by Trofim Lysenko, a poorly educated peasant’s son who rose to power in the 1930s as part of Stalin’s glorification of the common man. Lysenko’s bizarre theories were eventually discredited, but meanwhile a generation of geneticists lost their jobs because their work would have exposed Lysenko as a fraud. Some – including Belyaev’s own brother -- were imprisoned and killed.

Belyaev enjoyed a measure of freedom because of his success in developing valuable new genetic lines of mink. But the daring new project he was about to launch went far beyond his mandate to increase the value of fur production.

Belyaev was fascinated by the question of how animals had first come to be domesticated. The way farmers selectively breed domesticated plants and animals for desirable traits was quite well understood. But this didn’t explain how certain species had been domesticated in the first place. Or why so few species of plants and animals out of the millions on the planet had ever been domesticated - only a few dozen animals, mostly mammals, plus a few fish, birds, and insects such as silk worms and honey bees.

Scientists by now believed that dogs were the first species domesticated by humans, some 15,000 years ago, and that they had evolved from wolves. But no one really understood how wolves – animals that generally fear and avoid or act aggressively towards humans – developed into man’s best friend, an animal that is attracted to and trusts humans.

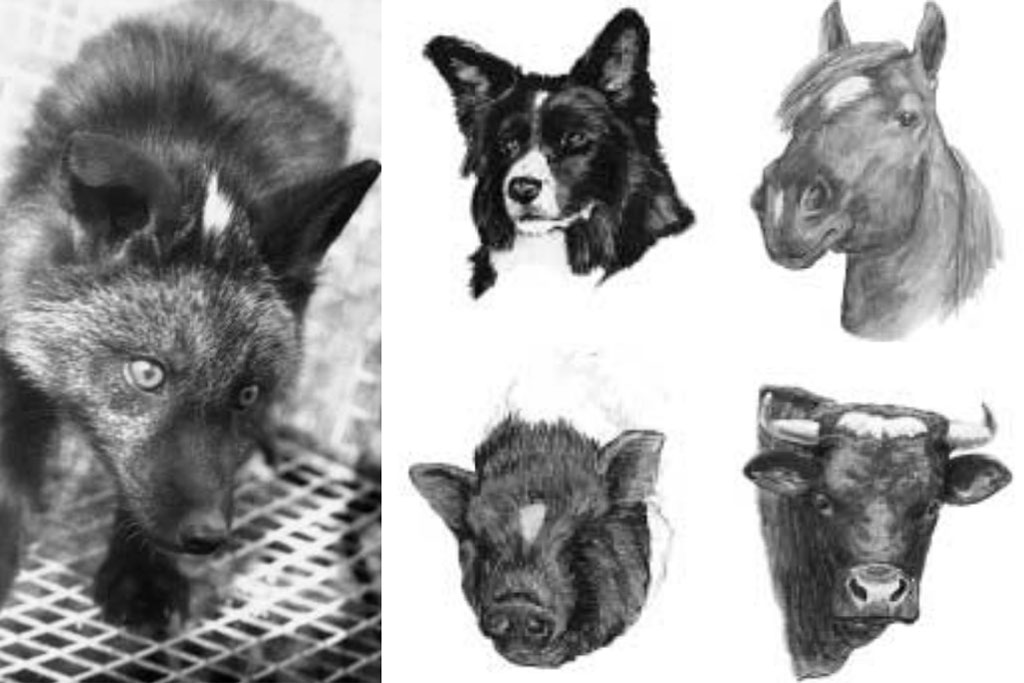

Belyaev was also intrigued by the fact that so many of the changes that occur in many different domesticated species were so similar. As Charles Darwin had noted, they often had patches of different colours on their coats. And they often retained physical traits from childhood that their wild cousins outgrew as they matured: floppy ears, curly tails, shorter snouts and babyish faces – neotonic features that make young animals so “cute”. But why would breeders have selected for these traits? Farmers received no benefit, after all, from cows with spotted hides or pigs with curly tails. So why had they emerged?

Belyaev had a theory that domestication – with all the qualities that distinguish domesticated animals from their wild cousins -- might be triggered by selecting for just a single trait: tameness. It had been suggested that dogs evolved from less aggressive wolves – individuals that would have been low-ranking in their own packs but were tolerated close to human settlements, where they gained access to a more reliable source of food and thrived. Belyaev wondered if this process might be replicated by repeatedly selecting the least aggressive foxes on fur farms for breeding.

One of the well-known features of domesticated animals – dogs, cats, cows, pigs -- is that they can breed several times a year, not just once like most of their wild ancestors. If farmed foxes could be bred more than once a year there would be a clear economic benefit – and this was Belyaev’s cover story as he approached a trusted colleague in Estonia that fateful day in 1952. Nina Sorokina was in charge of some 1,500 silver foxes on a large government-owned farm in a remote forest hamlet. She was surprised by Belyaev’s proposal, because silver foxes were generally quite fearful and aggressive towards people, but she agreed to begin selecting and breeding a group of the least aggressive animals.

The foxes Sorokina bred in Estonia provided the nucleus for a much larger project that Belyaev launched at a new research centre in Siberia as Lysenko was finally repudiated after Stalin’s death. The results soon followed, validating Belyaev’s ground-breaking theories of domestication. Within ten generations – barely a blink in evolutionary time -- foxes were being born that were noticeably tamer. These puppy-like foxes had floppy ears, piebald spots, and curly tails. Some of these pups eagerly approached humans with their tails wagging, behavior never seen before in foxes. As scientific knowledge of hormones evolved, it was confirmed that these newly domesticated foxes had far lower levels of stress hormones. In the next stage of the research, several of the tamest foxes actually lived in a house with one of the lead scientists, Lyudmila Trut, and soon acted very much like dogs.

The speed with which these changes in the physiology and behavior emerged confirmed Belyaev's radically new understanding of the process of domestication. Since Darwin, scientists had assumed that change could occur only in small increments over long periods of time, driven by a gradual accumulation of useful but random genetic mutations. The speed with which these new domesticated foxes evolved, however, suggested to Belyaev that the changes revealed a range of genetic variation that already existed within the original fox population.

This would explain why such a small number of plant or animal species has ever been domesticated. Wild horses, for example, must have had a wide range of genetic variation within their populations, facilitating domestication, while zebras – which have sometimes been somewhat tamed, but never domesticated – do not.

Belyaev was ahead of his time in proposing that important changes to physiology and behaviour might result without the mutation of genes, but rather through the activation or deactivation of existing genes in response to new environmental pressures -- in this case, the selection for tamer foxes. The disruption of long-established systems of genetic stability could provoke a complex suite of changes (curly tails, spotted coats, shorter snouts, etc.) in surprisingly few generations.

Belyaev’s ground-breaking ideas were, in fact, originally sparked by his observation of farmed mink, where he saw new colour strains – pastels, sapphires, violets, pearls – emerge less than 30 years after wild mink were brought onto farms.

Not least interesting, Belyaev’s work puts the lie to activist claims that farmed mink and foxes are “wild animals” that should not be kept in captivity. These species have been selectively bred on farms for more than 100 generations, resulting in significantly different colours, size, and behaviour. These are no longer "wild" animals.

The full story of this extraordinary research project has now been told for the first time in a wonderful book, How to Tame a Fox (And Build a Dog), co-authored by Lyudmila Trut and Lee Alan Dugatkin. Trut heads the research group at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics in Novosibirsk, and continues to lead Belyaev's fox project to this day. Dugatkin is a professor of biology at the University of Louisville and a science writer. Fur farmers and anyone interested in animals and domestication will find it a fascinating read!

FURTHER READING: How humans domesticated themselves. National Public Radio, October 31, 2020.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

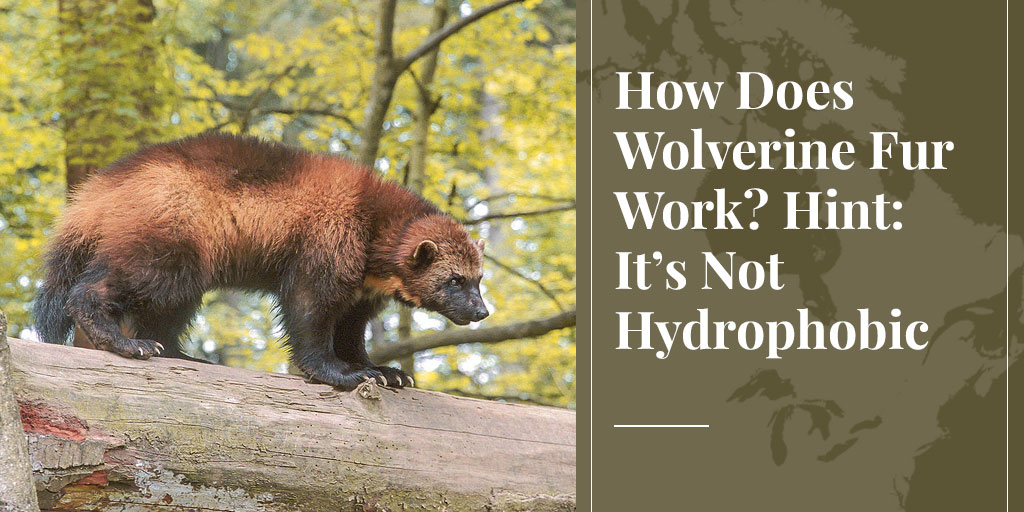

Conventional wisdom is clear on why, since time immemorial, wolverine fur has been the preferred material for hood trim in…

Read More

Conventional wisdom is clear on why, since time immemorial, wolverine fur has been the preferred material for hood trim in the High North. In essence, the thick, dark, oily fur is hydrophobic, which means it repels water, and thus prevents the build-up of frost caused by condensation of the wearer's breath. The only problem is, none of this is true.

While everyone agrees that wolverine fur makes the finest lining for parka hoods in sub-zero conditions, experts still don't have a clear understanding why. But they do know that it's not hydrophobic, it doesn't repel water, and, given the chance, it allows frost to build up just like any other fur.

Before we dispel the myths surrounding wolverine fur, here's some background. Wolverine fur is generally considered too long and the leather too heavy for use as whole coats. Instead, it is revered as trim for hoods by the Indigenous people of the Arctic and sub-Arctic, in preference to the more readily available (and therefore cheaper) wolf and coyote. But it's not entirely about functionality. Sometimes a strip of wolverine fur is placed next to the wearer's face, then surrounded with the long, silvery mane of a wolf, creating the famed "sunburst" ruff. The effectiveness of these ruffs in keeping the wearer warm has been scientifically proven, but they can also be spectacularly beautiful, so they're also worn for show!

SEE ALSO: Why fur trim keeps us warm. Truth About Fur.

So where do the myths about wolverine fur originate? Let's start with that confusing word "hydrophobic". It probably doesn't mean quite what you think it does, or even what your dictionary says.

When we talk of phobias (from the Greek phóbos, meaning "aversion", "fear" or "morbid fear"), we think of being repulsed by something. Hence the word "hydrophobia" was historically used as a synonym for rabies because sufferers often fear water (and liquids in general). From this, scientists came to use the word "hydrophobicity" to describe the behaviour of certain surfaces in the presence of liquids. Then, for whatever reason (laziness, misunderstanding, or lack of a better word?), dictionaries decided to use "repel" in their definitions. The Free Dictionary, for example, defines hydrophobicity as "the property of repelling water rather than absorbing it or dissolving in it."

Strictly speaking though, hydrophobic surfaces don't repel water at all. Two magnets of the same polarity, for example, repel each other, but hydrophobic surfaces don't repel water; they simply don't attract it. So even if wolverine fur were hydrophobic (which, as we'll see, it isn't), it would be wrong to say it repels water.

Many examples of hydrophobic surfaces exist in nature, all highly unattractive to water but not repelling it per se. Perhaps the best-known is the leaf of the lotus flower, after which the "lotus effect" is named. These leaves, and those of other plants like nasturtiums and prickly pears, use hydrophobicity to keep clean. Rain drops gather dirt while the surface architecture minimizes their adhesion to the surface itself. The same phenomenon is seen in the wings of insects like butterflies and dragonflies. Meanwhile, insects that live on water, like water striders, or spend most of their lives under it, achieve hydrophobicity through tiny hairs that make them virtually unwettable. Then there are penguins. One reason penguins excel at swimming is a layer of trapped air that coats them. Aside from providing insulation, this air reduces drag when swimming, and they can release it to accelerate when jumping out of water to land.

So how about the claim that wolverine fur prevents the formation of frost or ice from the wearer's breath? Again, it's a convenient explanation, but not actually true.

Research on the efficacy of fur trim was ramped up during World War II, when thousands of military garments made use of it, notably wolf and coyote. Writing in 1952 for the Journal of Mammalogy, Rollin H. Baker found wolverine out-performed both these furs, but not because frost didn't form on it. On the contrary, it did. It was what the wearer did next that mattered.

On the performance of wolf and coyote, he wrote: "As long as the fur trim can be kept dry, it functions quite well. However, once rime or frost has accumulated on wolf and coyote fur trim it cannot be brushed or shaken off. Therefore, in order to remove the rime, the garment must be warmed to the point where the rime either sublimates or passes through a liquid stage before it is evaporated. When air temperatures are low enough to cause direct freezing of the breath on the fur trim of garments, thawing caused by warm air currents from the body wets the fur. It thus becomes very uncomfortable to the wearer and also loses its ventilating quality."

All of which sounds thoroughly miserable, particularly if that thawed frost turns into the last thing you want on your hood trim: clumps of ice - icicles even - drawing heat away, disrupting air flow, and dragging your hood down with the sheer weight. (For an idea of how bad things can get, just Google "ice beard".)

So how did wolverine fur compare?

"Here is the point of difference between wolverine fur and most other furs," wrote Baker. "Frost or rime actually will form on wolverine fur at sub-zero temperatures, but it can be readily brushed off with a simple flick of the mitten and thus the fur can be kept dry. If the rime is not brushed off, the fur will become wet and uncomfortable, just as other furs do."

In other words, the myth that wolverine fur prevents the build-up of frost is wrong. Frost forms on wolverine fur just like on any other fur. What sets it apart is what Baker called its "frost-shedding quality" - the ease with which it can be brushed off.

In case you think all this talk of repulsion versus non-attraction, and frost-prevention versus frost-shedding, is splitting hairs, let's now address the elephant in the room. Is wolverine fur hydrophobic or not?

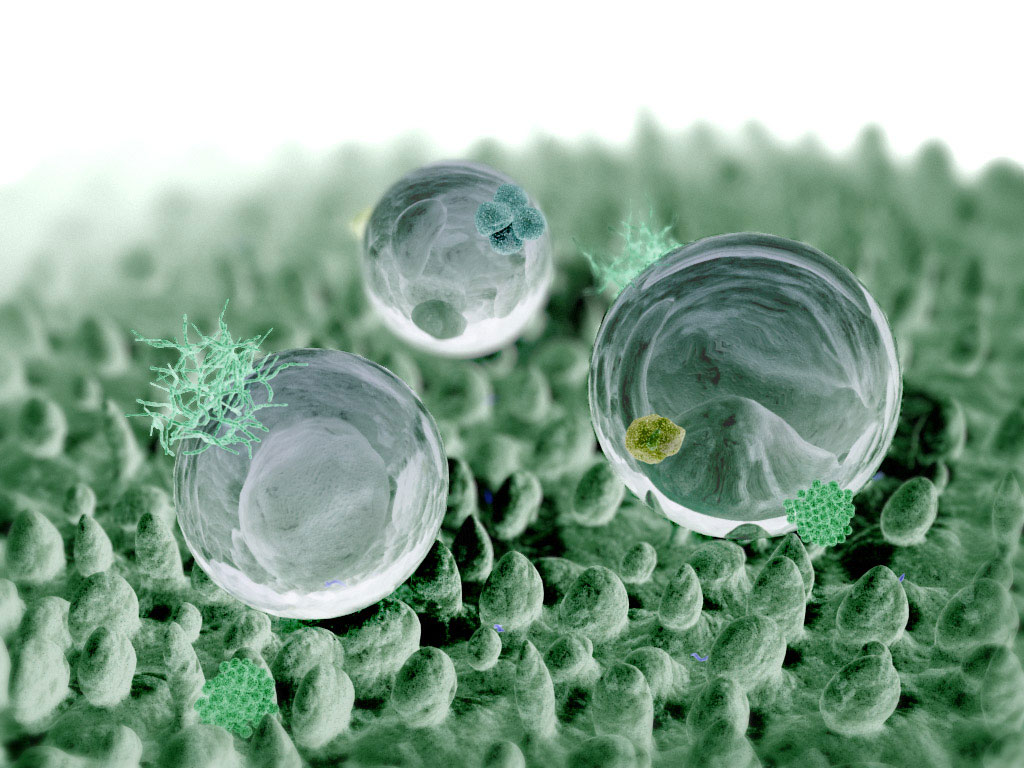

Scientists are extremely interested in hydrophobicity for a whole range of possible applications in things like aircraft, road and power-line maintenance, building construction, energy efficiency in cooling devices, car windshields, and protection of crops. So in 2012 Boris Pavlin, then at Carinthia University of Applied Sciences in Austria, subjected wolverine fur to a whole gamut of tests to see why it's so effective at "frost formation suppression".

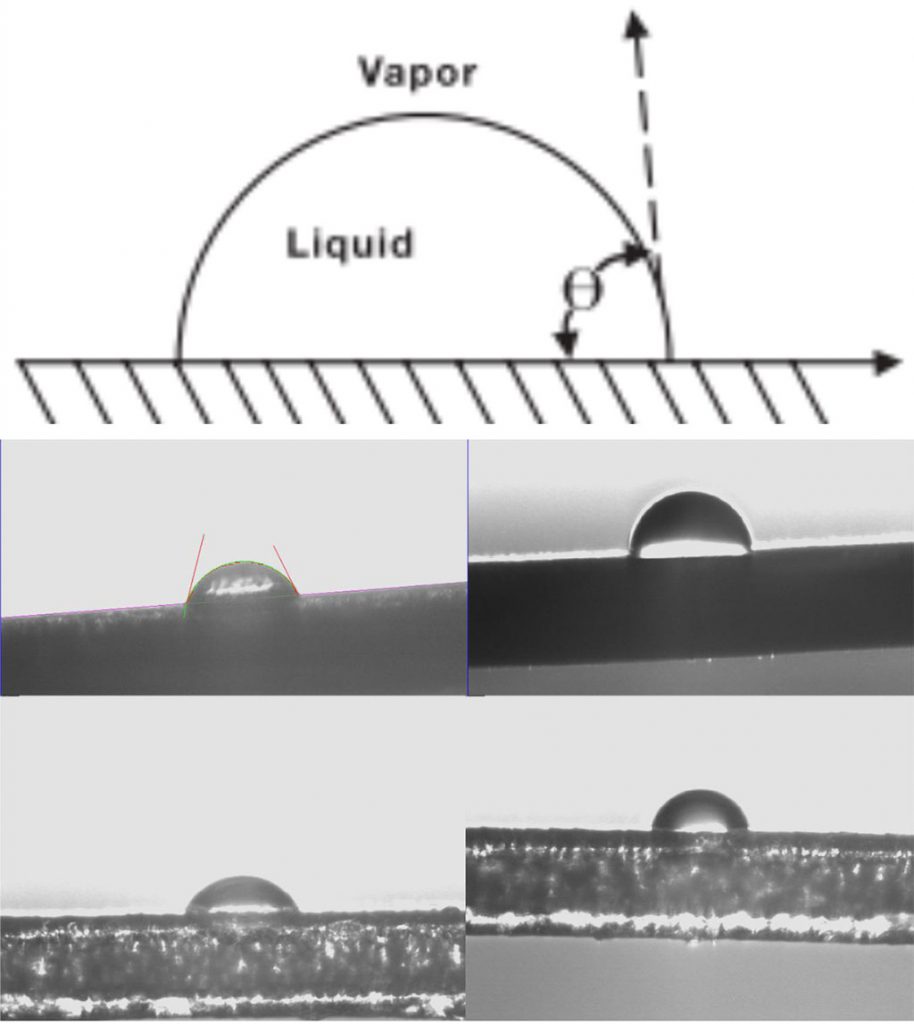

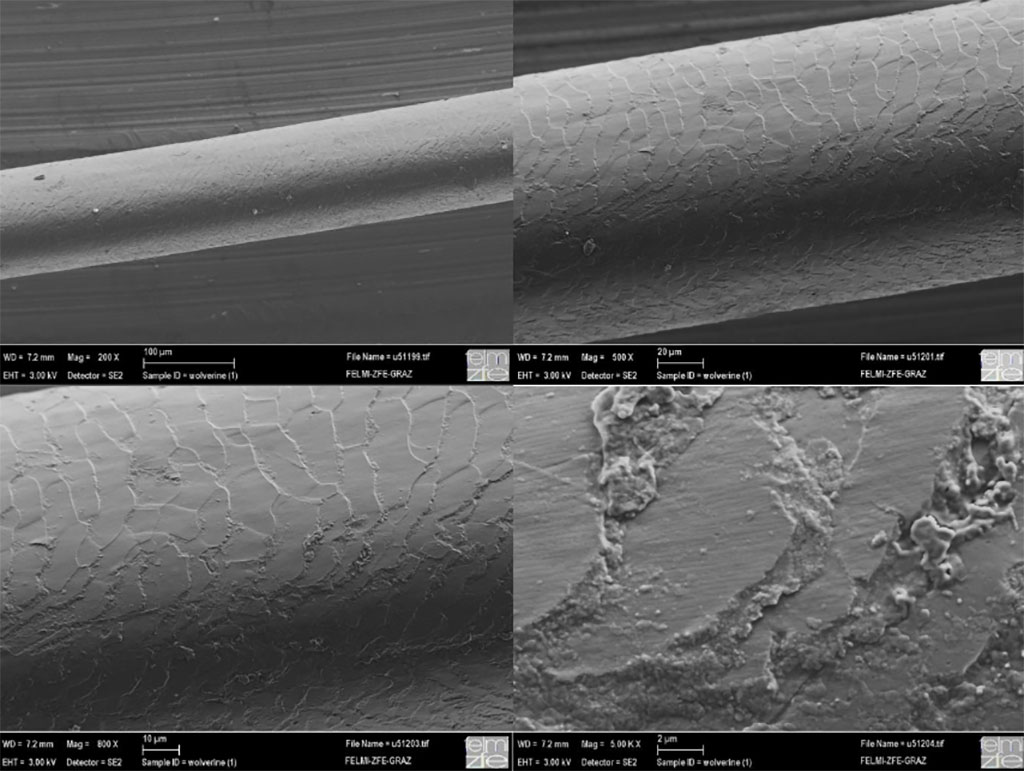

Pavlin's test for hydrophobicity was simply to photograph the contact angle between droplets of water at various locations on a wolverine hair (see photos above). Clearly, there is no comparison between these images and the lotus leaf we saw earlier, and Pavlin's conclusion was unequivocal: "the surface was NOT hydrophobic" (emphasis not added).

Sadly, there is still no clear understanding of why wolverine fur is so effective - or, to be precise, why it's so easy to brush frost off before it becomes a problem. But it seems certain that when an answer is found, it won't point to one factor alone.

One proposal is that wolverine guard hairs are uncommonly smooth, with no tiny barbs to stop frost from falling off. Using a scanning electron microscope, Pavlin confirmed that the middle parts of wolverine guard hairs are indeed smooth. The tips, however, showed a "very interesting pattern" of barbs.

He also tried freezing hair tips and testing for any abnormal surface electrical charge that might influence frost or ice formation, but found none (though he thought this should be revisited with optimal testing equipment). There were also no chemical substances on the hairs' surface. And in one test which seems unrelated to the purpose of his research but may prove useful to someone, he found the tensile strength of wolverine hairs to be remarkable as he could stretch them by more than 20%! But no silver bullet to explain everything.

"Many different strategies contribute to easy frost removal," he concluded, adding that "some questions remain unresolved and should be subject of further research." But he did at least come up with one definitive finding, which he states cryptically as: "A non-hydrophobic surface is superior to other existing approaches - a proof that the most obvious solution doesn't need to be the right one." In short, while it might seem obvious that wolverine fur is hydrophobic, it's not.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

A recent trip to the United Kingdom allowed me to conduct some unscientific research on common preconceptions about this damp…

Read More

A recent trip to the United Kingdom allowed me to conduct some unscientific research on common preconceptions about this damp and chilly nation. Are the natives really as fixated on Brexit as media reports suggest? Is opposition to fur as strong as we're told? And is veganism truly sweeping the land?

The UK is the spiritual home of the animal rights movement, so it’s not surprising that it also hosts some determined anti-fur campaigners. In 2000, England was the first country to prohibit fur farming (largely symbolic because there were so few farms), and now activists want to ban all fur imports. To this outside observer, the future of fur in the UK was looking grim before my recent visit. Now, I’m a little more optimistic.

OK, I’m not strictly an outsider. I’m English. But I’ve spent almost no time there for 20 years, so a month-long stay over Christmas gave me the chance to see whether my preconceptions based on media reports and hearsay matched reality.

As my plane touched down at London Heathrow on a dark and foreboding 4°C evening, my main preconceptions, of course, concerned Brexit. Did people really talk about nothing else? And, more to the point, was it fair to say that mere mortals could make no sense of this complex mess?

In close second place was my preconception about the likelihood of some sort of fur import ban. A campaign to this end got a lot of media coverage last summer, buoyed by a bevy of celebrities and stories of fur-vendors and wearers being harassed on Instagram. The Conservative government nixed the idea of a ban, but the main opposition party, Labour, was unsurprisingly more receptive, and with the political scene in turmoil (Brexit, again!) who knows what could happen?

My third preconception was that all the stories I’d been reading about veganism sweeping the UK must be exaggerated. Omnivores like myself tend to believe that veganism can never become a major trend, but what if we’re wrong? Ethical vegans (as opposed to the dietary variety who just think veganism is healthy) tend to share animal rights beliefs, so if vegan numbers were really swelling, the UK might become less fur-friendly than ever.

It was time for some first-hand observations.

My first objective was to see for myself how much fur was on the street.

This totally informal survey took in two quite different areas: London’s West End, with all its foreign and often well-heeled tourists, and a sampling of towns and villages across the county of Kent. From growing up in the region, I expected to see a smattering of mink and fox jackets in London, but very little in the way of full-fur garments elsewhere. And I was right. The southeast of England has never been a big fur market.

But here’s the news! Everywhere I turned, from London’s ritzy Piccadilly Circus to the tiny village of Downe, Kent, where my parents live, fur-trimmed parka hoods were everywhere. Trendy folk were wearing them, but so too were school kids, pensioners with grocery bags, and tough guys with workman boots. In an impromptu high-street survey in the coastal town of Folkestone, I estimated half of all Christmas shoppers were wearing them.

So you’re asking were they real or fake, and yes, the majority looked cheap and ill-kempt, and were almost certainly plastic. But as many as one in 20 looked spectacular, meaning top-notch fakes or real, and at least one in 50 was bona fide coyote. I don’t think that’s insignificant, especially in England at a time when animal activists are constantly claiming that real fur is taboo. They're wrong.

I saw no disapproving looks from passers-by at those sporting coyote, and I don’t believe that’s because anyone thought they were fakes. It’s not that hard to spot a real coyote ruff, particularly when it’s accompanied by a helpful Canada Goose logo. Rather, I imagined the wearers of cheap fakes were admiring the real McCoy enviously, wishing they could afford one of their own.

I don’t know whether this boom in fur-trimmed parkas will open the door to other furs (and shut down talk of fur bans for good), but it is clear that the look of fur - both fake and real - is now hugely popular and widely accepted in the UK. It was certainly a surprise that media reports had not prepared me for.

Gauging the popularity of veganism was another kettle of fish (to use a phrase PETA would rather we didn't). I just kept my eyes and ears open, and didn't have long to wait.

Whenever I go home, one of my first stops is my local pub, the George & Dragon, for a pint of bitter, a comforting reminder that no matter where in the world I pitch my tent I will always be English. Imagine my surprise, then, when I asked for a bite to eat and was offered the option of a vegetarian menu! I literally squawked and threw up my hands as if the barman had offered me a virus.

No, I don’t live under a stone and have even seen vegetarian menus in trendy eateries, but a good English pub is never trendy – or so I thought.

I soon learned that British diners are now thoroughly coddled when it comes to their dietary quirks. Many restaurants, stores and, yes, even pubs offer gluten-free vegetarian and vegan options, and a meat substitute called Quorn is all the rage. My own sister served Quorn “meatloaf” on Boxing Day, which I viewed with the same curiosity I normally reserve for unrecognizable roadkill.

For an expert’s analysis, I sat down with my old friend and sheep farmer Lizzie, who, virtue of two teenage daughters, has a finger on the pulse of all things trendy. When she informed me we were now in the month of Veganuary, I knew I was in for an eye-opener.

“Veganism has become terribly fashionable, for many of the wrong reasons,” she said. "The supermarkets have jumped on the band wagon and vegan food is everywhere - actually at the expense of vegetarian food.”

"People are increasingly being told about the damaging environmental effects of livestock production, and they believe that by becoming vegan they are helping to save the planet. But they are unaware that by rejecting meat and dairy products, their dietary fats now come from sources which contribute to the destruction of rainforests. 70% of UK farmland is under grass for very good reasons - agronomic and environmental. We are extremely well-placed in the UK to produce beef and lamb in a sustainable way."

So are all these vegans also animal rights activists, or at least sympathetic to the cause?

“There are a fair number of ethical vegans here, but only a few of them are animal activists. Most long-term vegans are calm and peaceful - they don't have the energy to be anything else. However, many of the new trendy vegans don't really care all that much about animals. It’s more to do with fashion, perceived health benefits, and their own woolly thinking born of a total disconnect with the whole concept of food production.”

And just to prove that Brits can’t stay off the subject of Brexit, she adds: “The one good thing that could have come out of Brexit would be leaving the Common Agricultural Policy. Sadly, we're going to bugger that up along with the rest of it. I'll be interested to see how long it takes these misinformed vegans to revert to meat-eaters once the food shortages kick in. I can't see them living on swede, a few stored potatoes and apples until the summer.”

In North America, it is not uncommon for people to write off the British as a bunch of animal-rights fanatics. But, as in all things, we should be cautious about making generalizations about entire cultures, especially when our only sources of information are the media.

With that in mind, I now offer these unscientific conclusions from my recent month of field work.

First, and for me the most fascinating, most Brits don’t seem to hate fur at all, at least not fur-trimmed parkas. This suggests the future of fur in the UK may not be so bleak after all, especially if new products can be developed and marketed that cater to emerging trends and lifestyles.

Second, the overwhelming majority of Brits are still omnivores, but the rise of veganism is very real. However, this may just be a passing phase, and there’s no reason yet to assume that today’s trendy vegans will become tomorrow’s animal rights activists.

And last but most definitely not least, it’s true: just mention the word Brexit and everyone within ear-shot pulls their shoulders back, puffs out their chest, and delivers their 2 cents’ worth. They'll then admit they really don’t know what they’re talking about!

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Unfortunately, this could happen to anyone working with fur these days, especially retailers selling any sort of fur or fur-trimmed…

Read More

Unfortunately, this could happen to anyone working with fur these days, especially retailers selling any sort of fur or fur-trimmed products.

A veteran North American retail furrier – who shall remain nameless here, to protect the innocent – has participated for the past ten years in a high-profile fund-raising fashion show, in support of a local charity. About a month before this year’s show, he spoke with the organizers who confirmed that they were looking forward to working with him again. Then the animal-rights bullies showed up.

Just two weeks before the event, he received a call from the fashion-show producer. She informed him that the Events Committee had decided they could not include his products in the show this year. “One of the sponsors is against fur,” she said, as if this explained everything. The committee had made their decision and nothing could be done, she told him bluntly.

And that might have been the end of the story, except this retailer is not the sort who likes to be told that “nothing can be done” ... especially when it involves mindless kowtowing to anti-fur bigots. Sensing that the show producer was not open to discussion, he went above her head and contacted the charity’s Events Coordinator. What he did next should be an inspiration to all furriers – and, indeed, to everyone who believes in democracy.

Here is a summary:

She promised to speak with her superiors. And, sure enough, 24 hours later the retailer received a call from the charity’s CEO. It was Friday afternoon.

“I wanted to call before the weekend so you wouldn’t have to worry; you’re back in the show,” she said. The activists were not “sponsors” of the event; they had bought a table, like many others. In any case, the Committee should never have made this sort of policy decision without consulting with her. “This is not the way we do things,” she said. The charity appreciated the support his company had offered for so many years; they were delighted that he was ready to participate again. Have a lovely weekend!

Two weeks later, the fashion-show evening was a wonderful success, with almost 500 people in attendance. “I was pleased to see that several of the charity’s board members placed bids for the fur scarf we contributed to the silent auction,” says the retailer.

“I was worried that the activists would make a fuss when my fur scene came on,” he says. “But there was nothing but applause. I found out later that the activists had cancelled their table when they learned that they couldn’t impose their will on the organizers. See how phony their support really was all along!”

The retailer sent a note to the CEO after the show, congratulating her on a wonderful evening – and thanking her for having the intelligence and integrity not to give in to the activists’ bullying tactics.

With fur season revving up again, we hope that his little story will provide encouragement to any retailer who is harassed by activists. Truth About Fur will be preparing a “tool kit” of resources you can use to defend your business, including blog posts like the one cited above.

And if you have a story about tactics that have worked for pushing back against activist bullies, please share it with us!

SEE ALSO: STANDING UP TO ANTI-HUNTING BULLIES - A CASE STUDY FROM ONTARIO

Sensationalized videos claiming to show “animal abuse” are sadly a fact of life these days for animal agriculture, and they’re often…

Read More

Sensationalized videos claiming to show “animal abuse” are sadly a fact of life these days for animal agriculture, and they’re often promoted (if not actually filmed) by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. One such video, dealing with wool production from Angora rabbits, premiered in 2013 and has gone unchallenged - until now. An Angora farmer in the US contacted us to raise some real concerns about this video, which we think are worth sharing.

Before dissecting the video, let's start with a backgrounder on Angora wool production.

There are two distinct types of Angora rabbit: those that moult, and those that don’t.

Those that moult have their wool plucked every three or four months, just before moulting begins. Plucking produces the best wool because most of the guard hairs are left behind, but it is time-consuming. Plucking leaves in place the incoming coat, although one breed, the French Angora, can be fed a depilatory which results in the exposure of bare skin. Here's a video showing how to pluck an Angora properly.

Angoras that don’t moult are sheared. Because the guard hairs are included, the wool is not such high quality, but collecting it is quicker and the yield is higher because wool can be sheared even from sensitive areas of the rabbit's body. Shearing is therefore more common in commercial operations. The most important commercial breed is the high-yielding and virtually mat-free German Angora. Ninety per cent of Angora wool production today is in China, and almost all Chinese farms raise German Angoras. Here's a video showing how to shear an Angora properly.

OK, it's time to watch the main attraction. If you find videos of animal cruelty hard to stomach, just give it a miss and take my word.

0:10 – 1:03: This rabbit is almost certainly a non-moulting German Angora, even though it looks very similar to a moulting French Angora. We can tell it's a non-moulting breed because its legs are tethered to what is called a stretching board. These are sometimes used, but not always, when rabbits are sheared.

PETA describes the stretching process as follows: "During the cutting process, their front and back legs are tightly tethered – a terrifying experience for any prey animal – and the sharp cutting tools inevitably wound them as they struggle desperately to escape." In reality, while rabbits being stretched for the first time might be nervous, they soon learn to relax. Stretching keeps the rabbit still and pulls the skin taut, thereby preventing nicks and cuts from the shears - the total opposite of what PETA claims. Here's an excellent video demonstrating how stretching is done.

Oh, but what's happening now? Having set the rabbit up for shearing, the man is plucking it right down to its skin! He is also applying far greater force than is ever needed to pluck a moulting breed. This is all wrong for two reasons. First, the rabbit is obviously in pain. Second, as US Angora farmer and advisor on this blog post Dawn Panda says, this could be called "worst business practice". "We see the wool being yanked off, guard hairs included, in a manner that will ruin the coat for several cycles," says Dawn. "It will damage the hair follicles and greatly reduce the quality and value of future harvests as new coats will grow in coarser and hairier. No one trying to make money would do that."

This raises a disturbing question. Are we seeing a non-moulting German Angora being forcibly, and very roughly, plucked just for the camera?

READ ALSO: "Saving Society from Animal 'Snuff Films;". Fur Commission USA.

1:04 - 1:17: Here a rabbit is being sheared, so we don't see any pink skin. It appears calm. At this point in the video, it is not clear whether this footage and the footage of a rabbit being violently plucked were shot on the same farm. We'll come back to this because, if all the footage is from one farm, the question is raised why one rabbit would be plucked and one sheared.

1:18-1:22: Here a rabbit that has just been sheared is shown suspended in the air by its front legs. This makes no sense, Dawn assures us. There is no part of Angora husbandry in which a rabbit would ever find itself in this situation. It can't even be claimed the rabbit fell off its stretching board because it's far too high. Once again, we can’t help but wonder if this bizarre scene was staged for the camera.

1:36-2:02: Here we see a parade of seven rabbits in their cages. Of these, the first three still have hair on their torsos and have been sheared. The next three have been plucked right down to their skin. The last rabbit cannot be seen clearly.

This scene suggests that the violent plucking at the beginning of the video and the shearing that followed took place on the same farm. And since commercial farmers generally don't have mixed herds of moulting and non-moulting rabbits, we can also suppose that all the rabbits shown are non-moulting German Angoras. The burning question is now unavoidable: Was the violent plucking of a non-moulting rabbit in the opening sequence staged for the camera? It would not be normal practice on a commercial Angora farm, insists Dawn.

"If animal lovers would use their heads, they wouldn’t be taken in by sensationalist publicity stunts," she says. "However, the addition of poignant music seems to ensure that one’s heart is going to overrule one’s head and voila! Misinformation is spread exponentially, the lie repeated until it’s accepted as fact. There are a number of excellent teaching videos on plucking and/or shearing Angora rabbits on YouTube; the lack of screaming, struggling or any pain is the norm, not the exception. This PETA video certainly does not reflect the reality of Angora farming as I know it!"

If PETA's Angora rabbit video was indeed staged to misrepresent normal practice, we should not be surprised. This ignominious tactic by animal activists traces its roots all the way back to 1964, when the urban myth about seals being "skinned alive" began with a film that was later proven to have been staged.

While people have a right to believe that humans should not kill or use animals in any way, they lose all credibility when they manipulate images to attack the reputations of those they disagree with.

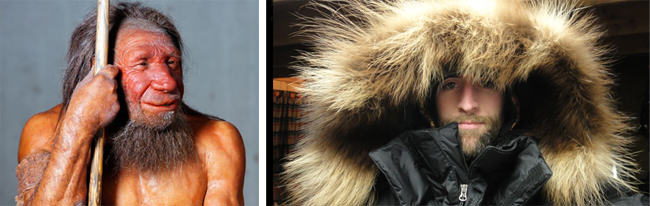

COOL FACT #1: Fur may have saved the human race New research suggests humans (Homo sapiens) survived the last Ice…

Read More

New research suggests humans (Homo sapiens) survived the last Ice Age and Neanderthals didn’t because humans were serious about fur clothing. Animal remains around Neanderthal sites lack evidence of furbearers, while human sites have fox, rabbit, mink and notably wolverine - the same fur still preferred today by Canadian First Nations for hood liners.

In the early 19th century, trappers came from far and wide to the US west coast to harvest huge populations of furbearers. It was these trappers, not the gold prospectors who followed, who opened up the west and put San Francisco Bay on the trade map. But no one remembers because no one named a football team after them. Go 49ers!

Next time you see the words "natural flavouring" on a food package, it might be referring to Castoreum, secreted from the castor sacs of beavers located between the tail and the anus. Usually it's used to simulate vanilla, but it can also pass as raspberry or strawberry.

The search for fur drove Europe's exploration and settlement of North America, and many of today's towns and cities began as fur-trading posts. In fact, much of the border between Canada and the US traces the territories once controlled by Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company and the Montreal-based North West Company.

Have you ever wondered where all the animal leftovers from human food production go? Fish heads, chicken feet, expired eggs, spoiled cheeses? If you live in fur-farming country, chances are they go to make nutritious mink food. And the mink manure, soiled straw bedding and carcasses are composted to produce organic fertiliser to enrich the soil, completing the nutrient cycle to produce more food.

In Nova Scotia, Canada, pilot projects are transforming mink wastes into methane for bio-energy production. In Aarhus, Denmark – the country that produces the largest number of farmed mink – the public transit buses already run on mink oil.

Crabs will eat just about any seafood you offer them, but so will seals and sea lions, and they'll trash your crab pots to get at it. Enter mink bait! Crabs find their food by smell, and apparently the smellier the better because they love mink musk. But seals and sea lions can't stand it and will give your pots a wide berth!

The national animal of Canada has been prized for its luxuriant fur for hundreds of years, yet wildlife biologists believe there are as many today as there were before Europeans arrived. They also believe coyotes, foxes and raccoons are more populous now than ever. Truly modern trapping, regulated to allow only the removal of nature's surplus, is a perfect example of the sustainable use of renewable natural resources!

SEE ALSO: Abundant furbearers: An environmental success story.

After being weaned from their mothers, farmed mink are often raised in pairs, preferably a brother and sister, and sometimes even threes. Farmers have learned that keeping siblings together results in calmer and healthier mink.

Fur garments are created individually, with all the cutting and sewing done by hand. Not counting all the work involved in producing the pelts, an “average” mink coat might take 35-40 hours of hand work, while an intarsia sheared beaver by Zuki could take 100 hours. That's longer than it now takes to assemble a car!

Each year, North Americans use about 7 million animals for fur. That's one sixteenth of one percent of the 12 billion animals they use for food. Yet animal activists focus more attention on the fur trade than on all other livestock industries combined. Go figure!

The fur industry is proud to state that one of reasons real fur is eco-friendly is that it biodegrades. Fake fur made from…

Read More

The fur industry is proud to state that one of reasons real fur is eco-friendly is that it biodegrades. Fake fur made from petrochemicals, on the other hand, just sits in landfills for centuries - though that is, admittedly, hard to demonstrate! So thinking it's time to walk the walk, we decided to do a little experiment. Join us now in the Great Fur Burial!

We've taken a mink stole and a fake fur vest, cut them into pieces, and buried them in the ground. At 3 months, 6 months, and then once a year for five years, we will be unearthing a piece of the mink and a piece of the fake fur and checking in on the biodegrading process. While our experiment is hardly scientific, we are endeavouring to ensure the results are as realistic as possible.

First, we found a real fur stole (100% mink) and a fake fur vest (80% polyamide and 20% polyester). We removed the lining from both.

Here is a closeup of the mink before the backing was removed ...

And here is a closeup of the fake fur ...

We cut both into pieces, all of similar size (mink on the left, fake on the right) ...

Then we dug a shallow hole, roughly one foot down, and placed eight pieces of each fur into the "fur grave". This happened on May 14, 2016. (Mink on the left, fake on the right.)

Then we covered them with dirt and turf ...

Now let's let Mother Nature do her work! See you in August, little fur pieces!

Read the other installments of this experiment:

The Great Fur Burial, Part 2: After Three Months

The Great Fur Burial, Part 3: After Six Months

The Great Fur Burial, Part 4: After One Year

SEE ALSO: New study compares natural and fake fur biodegradability. Conducted by Organic Waste Systems, Ghent, Belgium; commissioned by the International Fur Federation and Fur Europe, 2018.

In our last post, we exposed how activists lie when they claim that the World Bank condemned fur dressing as…

Read More

In our last post, we exposed how activists lie when they claim that the World Bank condemned fur dressing as “highly polluting”.

Today we turn our “Truth-About-Fur-Detector” to another oft-repeated but equally fraudulent claim.

Activists often insist that “a coat made from wild-caught fur requires 3.5 times more energy than a synthetic coat, while a farmed-fur coat requires 15 times more energy.” (see: NOTES, below)

These “facts” are attributed to “a study by the University of Michigan” or sometimes the “Scientific Research Laboratory at Ford Motor Company”. Wow, pretty credible sources, right? Except that a quick search reveals that neither institution ever published such a study!

This report does indeed exist, although it is very old – it was published in 1979. The author, one Gregory H. Smith, is identified as an engineering graduate of Michigan U., who worked for Ford. But he prepared his report at the request of The Fund for Animals (a Michigan-based animal-rights group), “to augment its arguments for abolishing the cruelties to animals resulting from the procurement of natural animals furs for human adornment.”

The methodology of this report is equally suspect.

According to Smith, more than 90 per cent of the energy attributed to the production of a farmed mink coat is accounted for by a single item: the feed used to produce the mink pelts. Smith claims that mink feed represents 7.7 million of the 8.5 million British Thermal Units (BTUs) he calculates is required to make a fur coat. But BTUs, scientific as they may sound, don’t tell the whole story. Like the mink themselves, mink feed is organic material. Specifically, mink eat the parts of chickens, cattle, fish and other foodstuffs that we don’t eat. Mink feed, in the language of ecology, is “a renewable resource". The petroleum used to produce poly-acrylic fake fur, by contrast, is a non-renewable resource. Comparing the energy used to produce natural mink and fake fur is comparing apples and oranges. (Or, more accurately: apples and the plastic bag you carry them home in!)

Furthermore, much of this abattoir and fish-packing waste would end up clogging land-fills if mink were not consuming it. Far from being an environmental “cost”, this recycling of wastes from our own food-production system can be seen as an environmental “credit”. (Mink also help to keep down the cost of human food, since food processors would have to pay to dispose of these wastes if mink farmers weren’t using them.)

Smith also misses the point in his analysis of wild-captured furs.

He guesstimates the amount of gasoline trappers might use touring their trap lines, heating their cabins – and even the energy required to make steel for traps that may be lost or require replacement. His numbers are arbitrary and questionable, to say the least. But, more to the point: he ignores the fact that furbearer populations would often have to be managed even if we did not use the fur – e.g., to protect property, control diseases and protect endangered species. Overpopulated beavers can flood roads, farmland, and forest habitat. Coyotes and foxes prey on livestock or the eggs (or chicks) of nesting birds; without predator control, it would be difficult to protect endangered whooping cranes or sea turtles. Raccoons and skunks spread rabies, and on it goes. Without fur sales, wildlife population control work would still have to be done, but trappers would be paid by the taxpayers – as they are in many European countries. (E.g., muskrat control in Belgium and Holland.) Again: the conservation work done by trappers can be seen as an environmental credit, rather than a cost!

Bottom line: the real wasteful BTUs expended here would seem to be in quoting this poorly researched and misleading “study”. We can only hope that Mr. Smith kept his day-job at Ford!

**************************

NOTES:

Here are a few examples where the "University of Michigan / Ford Motor Company" report is cited to claim that fur requires more energy to produce than fakes:

The Fur Council of Canada’s Fur is Green campaign clearly caught animal activists by surprise. In their scramble for a…

Read More

The Fur Council of Canada’s Fur is Green campaign clearly caught animal activists by surprise. In their scramble for a rebuttal, they have resorted to fabricating “evidence” about fur's environmental impact that sounds credible – at least until you check their sources!

One of the most commonly-repeated activist claims is that “a World Bank Report has shown that fur dressing is the third worst polluting industry, following pesticides and fertilizers, synthetic resins and plastics.” (see: NOTES, below)

If true, this would be a serious charge, so I hunted down the original study. The report in question is The Industrial Pollution Projection System, produced by the World Bank Policy Research Department (Policy research working paper #1431, by Hemamala Hettige et al.) This study was drafted in March 1995, based on 1987 (27-year-old!) US statistics.

Reading through this highly technical econometric study we learn that “Conclusions are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank”. Interesting. Also that “Sectorial pollution is thought to be quite responsive to effective environmental regulation in many cases…” (p.9, E-4) Encouraging, because environmental protection regulations have certainly improved considerably over the past 26 years. But let’s read on ...

Ah, finally, there it is: a table listing the most polluting sectors. And what do we find? The sector listed in third place for environmental pollution is clearly identified as “Leather tanning and finishing” (ISIC Code # 3231, Table 4.1, p.23) – NOT “fur dressing and dyeing” (ISIC Code #3232). Fur dressing is a completely different process using much more benign chemicals, because fur dressers must protect the fur and hair follicles. (Leather tanners have no such concerns: they want to remove the fur.) In fact, fur dressing is not even listed in the top 75 polluting industry sectors by the World Bank report! (pg. 23)

Digging further into this study, we find a more extensive list of industry sectors, summarizing their “toxic pollution intensity” (pounds of pollutants per million $ of output.) Here we find confirmation of what common sense would dictate: fur dressing produced only 15% of the air pollutants, 9% of the water pollutants, and barely 7% of the land pollutants compared with leather tanning. (Pg 47.)

In conclusion: it is completely false to claim that the World Bank identified fur dressing as a highly polluting industrial sector. This study showed no such thing. The activists who first quoted this report either don’t understand the important difference between fur dressing and leather tanning, or intentionally misrepresented the findings.

In my next posts we will take a closer look at two other “studies” that are repeated referenced by activists to challenge the fur trade’s environmental credentials.

**************************

NOTES:

Here are a few recent examples of activists (falsely) claiming that the World Bank report cited fur dressing as one of the most polluting industrial sectors:

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.