As the cold weather settles in for another few months, I cuddle in my small country home on the Bay…

Read More

Cultural Heritage

After 50 Years, Fur Trade Turns Tables on Activists

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurWe are the people of the fur trade and we will be silent no longer! That is the new rallying…

Read More

We are the people of the fur trade and we will be silent no longer! That is the new rallying cry of our proud and historic trade, and it's long overdue.

It is hard to believe that the debate about fur has been raging for a full half-century – and a bit troubling to realize that I witnessed it all!

And while it is great to see all the fur on fashion runways and in the streets this winter, we still have a way to go to repair the damage caused by 50 years of activist lies, to reassure consumers that fur is produced responsibly and ethically.

Spotlight on Sealing

It was in March 1964, that a film on Radio-Canada, the French-language network of Canada’s public broadcaster, rocketed the northwest Atlantic seal hunt into the media spotlight for the first time. No matter that the shocking scenes of a live seal being poked by a sealer’s knife (“skinned alive”) would later prove to have been staged for the camera. (1)

In the 50 years that followed, the modus operandi of a lucrative new protest industry was refined: shocking images of questionable origin, celebrities to attract media attention, and emotional fund-raising campaigns that generated piles of money to drive more campaigns.

Markets for sealskins were weakened (with a US import ban in 1972 and a partial European ban in 1983), but the newly formed International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) was soon pulling in $6 million annually – more than 3,000 Canadian sealers made risking their lives on the ice floes each Spring. Greenpeace and other groups jumped onto the gravy train, with help from Brigitte Bardot. (2)

In the 1980s – with wild furs more popular than they had been since the Roaring Twenties – the protesters turned their newly-honed media, fund-raising and political skills against trapping (3), a campaign that resulted in the European Union banning jaw-type “leg-hold” traps, in 1997. No matter that traps used in Europe were untested or that other methods used there to control wildlife (e.g., poisoning muskrats in Belgium and the Netherlands) had far-reaching animal-welfare and environmental consequences. Canadian diplomats were told: “Don’t worry about your scientific studies, don’t you understand that this is about politics?”

While campaigns against sealing and trapping continue, the anti-fur focus has now shifted to calls for a ban on fur farming – but the tactics are the same.

Absent: Voice of the Fur Trade

Throughout this debate, one voice was conspicuously absent: the voice of the people whose livelihoods and reputations were being attacked. There are several reasons for this, including the imperatives of modern media, where confrontation is “news” and “celebrities” are irresistible. Hunters, trappers and farmers, moreover, do not live in cities where most journalists are based, so they are rarely heard.

The structure of the fur trade itself – small-scale, decentralized and artisanal – also made it difficult for the industry to muster an effective response. And it didn’t help that those closest to the media and consumers – retail furriers – have little knowledge of production issues. Asking a furrier about trapping standards makes about as much sense as asking a seafood chef to explain fisheries management policy.

All this is about to change. After 50 years of turning the other cheek, the fur trade is finally speaking out more effectively. Under the banner “Truth About Fur”, fur farmers, trappers, biologists and veterinarians are setting the record straight.

Animal Activists Scrambling

The reaction of animal activists is revealing. Used to having the soapbox to themselves, they are scrambling to block or discredit the industry’s voice. I have experienced this personally.

When we refute lies or misinformation on-line, it doesn’t take long before a cyber-bully tries to shut down discussion. Rather than risk having their dogmatic beliefs shaken by facts, they shoot the messenger. Typical attacks include: “He’s paid to write this, don’t listen to him!” “He’s a fur industry troll!” Recently I was called “a sock puppet”.

SEE ALSO: MINK LIBERATION : 5 FACTS THE ALF DOESN'T WANT YOU TO KNOW

I suppose it is better to be a sock puppet than a marionette, which would mean that someone was pulling my strings. But the bad news for these cyber-bullies is that we are not puppets. We are the people of the fur trade, and we will be silent no longer.

If the vicious lies and slanders leveled by activists against the fur trade for the past 50 years were directed at any other group in society, they would be denounced as hate crimes. It’s time that animal activists were exposed for what they are: intolerant bullies with little understanding of modern environmental thinking.

Aboriginal (or other) trappers do not need lessons about respecting nature from urban activists. Mink farmers do not need lessons about caring for animals from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PeTA). The fur trade is not a crime against nature; it is a prime example of “the responsible and sustainable use of renewable natural resources”, a principle supported by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and every other environmental authority. These are some of the facts that are documented by Truth About Fur.

It is encouraging that close to 500 international designers now include fur in their collections, compared with only about 40 in the early 1990s. And it is wonderful to see people of all ages with coyote and fox trim on their parkas this winter. But it is especially satisfying to know that, whatever people choose to wear, the fur trade’s story is finally being told by the people who live it.

* * *

1) Alan Herscovici, Second Nature: The Animal-Rights Controversy (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1985; Stoddart Publishing, 1991), p. 74.

2) Herscovici, p. 70.

3) Herscovici, pp. 117-162.

Taking New Trappers on Trapline Is Fun, Helps the Cause

by Jim Spencer, executive editor, Trapper & Predator CallerWhen I started trapping in 1959, it was a lot easier than it is now. Oh, sure, there’s more information…

Read More

When I started trapping in 1959, it was a lot easier than it is now. Oh, sure, there’s more information and better equipment available these days, but it’s a lot more difficult to actually start trapping today than it was a half century ago.

Urbanization is one reason. The population of the United States has shifted from predominantly rural to predominantly urban, and fewer kids (adults, too, for that matter) live close enough to trapping country to make it work. I was a town kid too, but it was a small town, and my bike could get me beyond the city limits in five minutes. That’s often not the case today, and even where it is, today’s world isn’t the one I grew up in. Turning a kid loose on a bicycle before daylight isn’t such a wise idea in many areas.

Also, there’s the change in public attitude about hunting, fishing and trapping in general. According to the 2006 National Survey of Fishing, Hunting and Wildlife-Associated Recreation, in my home state of Arkansas, which is less urban than many, only 301,000 residents hunted that year. That’s about 12 percent of the population. Trapping is included with hunting, and I’d be very surprised if 5 percent of those 301,000 folks trapped, but for argument’s sake, let’s say they did. That gives us a total of 15,050 trappers in my state, at most. There’s probably considerably less.

The situation is much the same elsewhere. When the percentage of active trappers is that low, it’s hard for somebody who wants to learn more about trapping to find anyone with similar interests. And when you can’t find anyone who shares your interest in something, guess what usually happens? Yep, your interest wanes, too, because it’s not much fun unless you can share it with someone.

Some Are Rookies, Some Trapped When Younger

That’s where us gray-whiskered veterans come in. Thirty years ago, I didn’t really have time to take someone under my wing on the trapline. I was pedal to the metal from Day 1 to Day Last, catching as many animals as I possibly could, because I had a houseful of kids and a dollar bill looked as big as a saddle blanket. Simply put, I couldn’t afford to take the time to help a rookie get started.

But now that’s not the case. I’m far from rich, but the crushing financial pressure is gone, and for Bill and me, the trapline is a more leisurely thing. Don’t misunderstand though. We still work hard, and we put up decent numbers for a couple of geezers, but neither of us is out there because our kids need shoes. And so we take interested folks on our line from time to time. Some are rookies just getting started, some are middle-aged guys who trapped when they were younger, and some are men and women who’ve never held a trap in their hands but want to see what it’s all about.

SEE ALSO: ONTARIO TRAPPERS PROTECT PEOPLE AND PROPERTY

The days when we have guests on the line are among the most enjoyable of the season. We usually don’t get as much done, because we’re answering questions and showing our guests what we’re doing and why. It slows us down, but we both enjoy it and are more than glad to do it. We’ve never discussed it much, but I think the reason Bill and I both enjoy having guests is that we’re helping promote trapping to non-trappers, either by helping a newbie get started or by showing a non-trapper first-hand that we’re not the bloody-handed barbarians the PETA folks make us out to be.

If you’ve never taken a kid, a beginning trapper or an interested non-trapper on your line, I recommend it. Not only will you enjoy it, but you’ll also be helping the cause.

Trappers Must Educate Non-Trappers About What We Do

by Jim Spencer, executive editor, Trapper & Predator CallerThe TV news item was about the upcoming duck season, and the soundtrack in the background was a recording of…

Read More

The TV news item was about the upcoming duck season, and the soundtrack in the background was a recording of somebody blowing a duck caller. The calling wasn’t bad, but what ruined it for me was the film clip they were running to illustrate duck hunting.

They were filming a flock of coots.

Unfortunately, that sort of stuff is pretty common on today’s television and movie programming. Pay attention, and you’ll see it all the time. I bet I’ve watched a dozen movies where they show a flock of cranes or ibises or some other species that flies in a V formation, accompanied by an overlaid soundtrack of - you guessed it - goose music.

Things like this are laughable, but they ought to also serve as warning flags. Every instance should remind us that not everyone is as knowledgeable about things outdoors as we are, and that simple but profound fact can (and often does) come back to bite us. In fact, the general lack of knowledge of the public about nature might well be the biggest problem we trappers, hunters and anglers face.

Sure, there are plenty of other things for us to worry about - loss of habitat to urban encroachment, shrinking access to public and private land, decreasing recruitment of young people into the outdoor lifestyle we know and love. But at the end of the day, none of those things will matter if our legal right to trap gets taken away at the ballot box.

And slowly but surely, that’s what’s happening. This year, for example, there was a petition drive in Montana to get an initiative on the November ballot prohibiting trapping on any public land in that state. (See Toby Walrath’s piece in the November 2013 issue of Trapper & Predator Caller for more on that.) They failed to get sufficient signatures this time, but if this thing passes in the future, more than a third of Montana would be closed to trapping.

Montana wouldn’t be the first state where it’s happened, either. It’s already against the law to trap on public land in Arizona and Colorado, and trappers have been so restricted and legislation-crippled in states like California, Florida, Massachusetts and New Jersey that I swear I can’t understand why any trapper would live there.

Coots Instead of Ducks, Cranes Instead of Geese

The reason this has happened, and the reason it continues to be a threat, goes right back to that coots instead of ducks, cranes instead of geese thing - a widespread lack of knowledge in the non-hunting, non-trapping public about all things wild. Most of these folks aren’t necessarily against hunting or trapping. They’re not anorexic, wild-eyed vegans. They eat meat just like we do. Nor are they stupid. They just have no interest in hunting or trapping. That’s all. And so they don’t bother to learn anything about it.

But they care about wildlife in an abstract, feel-good sort of way, and that’s why they’re susceptible to the exaggerations, half-truths and flat-out lies the zealots on the bunny-hugger side of the fence keep throwing at them. For example, it’s true what the anti’s say, that the lion does sometimes lay down with the lamb. But what the anti’s always forget to mention is that the reason the lion does so is so it can more comfortably eat the lamb.

It’s up to us to stop this brainwashing of the non-hunting, non-trapping public, and the most effective way to do it is personal communication. Every trapper has many friends and family members who don’t hunt or trap. These folks would be more inclined to believe us than they would be to believe some complete stranger telling them trapping and hunting are evil. However, they won’t get our side of the story unless we tell them.

Are you doing that with your friends and relatives? If so, thanks very much, and keep up the good work.

If you’re not, you’re part of the problem.

On a recent Saturday I attended a small trapper gathering and I must say I always walk away from these…

Read More

On a recent Saturday I attended a small trapper gathering and I must say I always walk away from these events having learned a great deal.

Most years the big take-away is learning about the habits and activities of various furbearers and man’s attempt to catch them. Honestly, you can tip your hat to the bowhunter who ends their season with a nice new mount for the wall, but I will always have more respect for the trapper who knows the ins and outs of his passion so much that he can fill a pickup load of beaver … or coyote … or some other crafty, wary species.

Indeed, in the outdoors world for my money the accomplished trapper is the real rockstar deserving the utmost respect. This person has to know his sport so well that he can predict that a critter will step on a few square inches of a trap pan in order to achieve success. Certainly I’m not discrediting the hunter in any way. Instead, if you’ve never been closely aligned with someone who traps to learn what it takes … you’re missing a truly wonderful outdoors experience, in my opinion.

Now, some might say trappers do it for the money. To that I would say GET REAL! The money? Oh, sure there’s the money element involved with preparing and selling furs, but very few trappers I know make much more money then they end up spending on supplies, on gas to run their line … not to mention the hard work involved with catching and putting up fur in preparation for auction.

I’ve been a recreational trapper since the age of 15 so I know what it takes. Commitment. Ambition. Discipline. Positive attitude. Those are just a few of the many qualities that go into a successful trapper. And while money can help motivate a person to get out of bed each morning to check the lines … it simply does not very often make a living for many people.

As I watched Leon Windschitl from the Minnesota Trappers Association give his demonstration showing the finer points of fur handling, it suddenly occurred to me how much work is involved with trapping. First off, there’s the work phase where you need to outsmart the animal. Specialized tools, techniques and tactics might work in some areas, but then not in others. There’s no guarantee for success in trapping, just like there isn’t in hunting or fishing.

Now, some trappers might stop right there and simply sell the animal in the carcass to the fur house. I’ll admit, this is what I often do because my process for skinning and preparing is not a streamlined operation. Others, however, realize the work is only beginning. Skinning the critter (depending on your skill level) might take five to ten minutes or more. Then comes the fleshing and stretching aspect … not to mention the combing and cleaning that is often necessary to make the fur look its best. Even the stretching and the drying demands time and lots of attention.

All in all that $30 raccoon is hardly easy or quick money for the trapper’s pocket. As a trapper, to do things the correct way takes lots of time, patience and effort often when weather conditions are less than ideal.

Especially this year. Preliminary fur markets are looking somewhat depressed so trappers will likely have less competition on their lines. That also means less money in the pocket when the seasons end. Indeed, this year when you see trappers out tending their traps realize how this year more than others the folks setting steel in the river ways and fence lines are doing it for a true love of the sport … and not for a means to get rich in the pocketbook.

Yes, I have a lot of respect for trappers and the sport of trapping. Always have and always will.

5 Reasons Why I Support the Canadian Seal Hunt

by Alexandra Suhner Isenberg, former Online Communications Director, Truth About FurTwo years ago I went to NAFFEM, a large fur trade show in Montreal. I was invited as a blogger, to…

Read More

Two years ago I went to NAFFEM, a large fur trade show in Montreal. I was invited as a blogger, to check out the beautiful pieces and choose some of my favourite items for sale at the show. I am a huge supporter of the Canadian fur industry (read about my reasons here) but I’ve been less vocal about the seal hunt, primarily because I didn’t have enough information to make an informed opinion about it. Well, now I do, and I would like to share it with you because I think it is important.

1. Seals are a sustainable resource and are in abundance. We live in a world where resources have become an issue, and many of us are choosing to consume products that come from renewable resources. Seal is a great example of this – there are tons of them in Canada and they are not at all at threat of becoming endangered.

Speaking of sustainability, seals are part of the reason why fish stocks are very low (although overfishing is also a big issue) and the seal hunt not only provides jobs and resources for the hunters, but also allows the fish populations to regenerate (a bit.) All major conservation groups will agree that a responsible use of resources (like hunting seals for food and clothing) is a good thing, and is often the central principle of modern conservation.

2. Seals are local. The green topic is a big one right now, and part of the green movement focuses on buying local.

Canada has a lot of great resources, but when it comes to fashion, few are 100% Canadian. Nearly all of our fashion products are in some way sourced from overseas (whether it be raw materials or construction) but seal skin and wild fur are 100% free range, local products.

3. The seal hunt supports Canadian communities. There are two major seal hunts in Canada, one in the Arctic sea (seals hunted by Inuit people) and one on the East Coast (a commercial seal hunt.) Both provide jobs and resources for those people. The meat is eaten, the fat is used for a variety of products, and the skin is sold so that these people can support themselves.

Food, as you may know, is extremely expensive in the Arctic, and there are limited jobs in that area, or in the Maritimes. The seal hunt is a very important Canadian industry for the people who depend on it.

4. The seal hunt is not inhumane. The animal rights activists will have you believe that the seal hunt is inhumane, but this is not the case.

First of all, most seals are killed with rifles (not clubbed to death.)

Secondly, there have been numerous studies done on the seal hunt, and biologists and veterinarians have all agreed that the seal hunt is no less humane than any other hunt.

SEE ALSO: EU SEALING POLICY IS HYPOCRITICAL, UNDEMOCRATIC

5. The media paints an unfair picture. My question, after having learnt all the above, was why does the seal hunt have such a bad reputation? There are two answers to this.

First of all, seals are cute, and people are more likely to be protective of cute animals. If we were all truly concerned about cruelty and sustainability, why aren’t we doing more to save fish? Many species of fish are far more at risk than seals, yet their not-so-cute appearance doesn’t exactly inspire people to campaign for them. (Notice how we care more that our tuna is “dolphin safe” but not so much if that particular tuna is endangered.)

Secondly, the seal hunt is much more visible than other hunts, and the access to it allows for more imagery. The seal hunt happens in certain places at very specific times, and so it is very easy for activists to turn up and take photos of blood on the ice. Those same activists aren’t invited into abattoirs, and therefore we don’t have the same images in our head of cows or sheep. The fact that seals are cute, and that we have access to photos of them being killed, means the seal hunt has been very unfairly portrayed by the media and activist groups.

Many of us are so far removed from nature, farming, and hunting, and it is so easy to forget that our food comes from the land. While I will admit I don’t like seeing photos of any dead animals, I do appreciate the process and am under no illusions about the realities of eating meat and wearing animal products.

For those of us who do choose to consume animals, the best we can do is consume sustainable resources that are treated humanely – and the seal hunt is just that.

What is the appeal of the reality TV show Mountain Men, and others in the same genre? If harvesters of…

Read More

What is the appeal of the reality TV show Mountain Men, and others in the same genre? If harvesters of nature’s resources, and not least the fur trade, can answer this question, they can apply the lesson learned to their own public relations, and in so doing win over millions of new supporters.

First, some clarification. Yes, Mountain Men is reality TV, but not of the kind that imprisons a bunch of misfits on an island to tear one another’s throats out, with instant celebrity status for the winner. Mountain Men is the other kind.

Mountain Men is about the daily lives of men who have opted to live cheek to jowl with nature, no matter what she may throw at them.

Or in the words of the History Channel, which airs the show: “Using ancient skills and innate ingenuity, these men fend off nature’s ceaseless onslaught, carving out the lives they’ve chosen from a harsh and unforgiving landscape.”

The audience relates at a visceral level to the painful, joyous or scary experiences of these shaggy-bearded, unkempt men with questionable hygiene and (apparently) masochistic tendencies.

Paradoxically though, many in the audience, like me, are city dwellers whose lifestyle is the antithesis of a mountain man’s. Why are we drawn by a lifestyle we go to such pains to avoid?

We have “guys” to change our oil, do our dry cleaning, mow our lawns and deliver our pizzas. We even boast about them as if somehow we deserve credit for their performance. “My mechanic is the best!”

And for sure, not one of us has ever made our own bullets, then shot a squirrel with a firearm that belongs in a museum, then cooked it and chewed on a piece of meat the size of a pinky and declared it good eatin’.

The fact is, though, that millions of us fantasize about doing just that!

Two Poles and a Jar of Worms

If you don’t know where I’m coming from, consider the ubiquitous angler. If you’re not an angler yourself, it’s almost certain your neighbor is.

Angling is one of the most popular pastimes for men (yes, it’s a manly thing) whose working lives are spent pushing papers around a desk, and there’s a good reason why.

It’s a call of nature we cannot resist, an instinctive drive to provide for our families by using our wits. A trip to the supermarket just doesn’t cut it.

And that is why, week in, week out, rain or shine, we populate river banks, catching little or nothing, staring at the water and dreaming. Dreaming how grand life would be if someone would actually pay us to do this.

And when our sons are old enough, they join us willingly (or so we like to believe) to bond over two poles and a jar of worms. If the fates are kind and we bag a couple of minnows, we char them black over a fire and lie to each other about how they taste better than anything Mum prepares with all her fancy recipes. Good times!

For other men, nature’s call is to hunt or trap.

Not Just Mountain Men

So how can the fur trade learn from shows like Mountain Men, and apply what it learns in its public relations?

We start by recognizing how popular this genre is, of folk living from nature, by their wits.

To name just a few shows with much the same formula as Mountain Men, we have: Swamp People (same hairy humans as Mountain Men, but hunting alligators); Outback Hunters (much like Swamp People but with Aussies hunting crocs); Lobster Wars; Lobstermen: Jeopardy at Sea; Wicked Tuna; Swords: Life on the Line, and so on.

Then there’s the granddaddy of them all, Deadliest Catch, the award-winning saga of crab fishermen trying hard not to drown or get minced in machinery. Now in its 10th season, Deadliest Catch has set record ratings in its class across both males and females, in all age brackets.

And we haven’t even touched on the survivalist genre featuring Bear Grylls (Man vs. Wild) et al. eating anything which once had, and sometimes still has, a pulse.

Don’t worry about the ratings. The mere fact that the cable TV powerhouses of History, Discovery and Nat Geo keep churning these shows out is proof enough of their appeal. Just this June, Animal Planet got in on the act with Beaver Brothers.

So Who Are They?

Next we try to identify who the audience are by understanding who they are not.

They are not drawn to shows like Mountain Men in the same way audiences are drawn to, for example, American Chopper or Counting Cars. The latter are unabashedly aimed at the millions of bikers and gearheads out there who lap them up because, well, they’re about them!

No, Mountain Men does not survive on an audience of mountain men, any more than Swamp People relies on swamp people. Even if all the mountain men, swamp people, crab fishermen, lobstermen and croc hunters in the world tuned in to an episode of Deadliest Catch, they’d hardly make a blip in the ratings.

So let’s say the bulk of the audience for this genre represents a cross-section of society, from diverse backgrounds, but with a few things in common that do not include risking their lives on a daily basis to catch dinner. And one of those things is that they support the harvesting of animals for human benefit.

Like most people, they’re probably not vocal in their support of this, and if asked what they think of animal rights activists, will probably reply, “a bunch of wackos”.

But they are nonetheless important allies. They are the people who, when push comes to shove, ensure that the animal rights movement does not have its way at every turn. They vote, they sign ballots, they pay membership dues to hunting and fishing associations that represent their interests, and they pay license fees that fund wildlife management and conservation efforts.

So are we catering to them, nurturing them to become vocal advocates not just of a lifestyle, but more importantly of the larger picture of man’s place in nature? Not much. Are they equipped with the knowledge to become such advocates? Definitely.

How Things Work

To cater to an audience, you have to know what interests it and what puts it to sleep, and most fur trade PR is not going to keep a mountain man wannabe on the edge of his seat.

The fur trade aims its PR primarily at two audiences: fashionistas, and people who are still undecided on whether they favor using animals for human benefit. This second audience, of course, includes a never-ending supply of youngsters who’ve never heard the arguments before.

High fashion is the biggest life force driving the fur trade, with trickle-down effects on everything from high street retail to the prices producers get for their pelts. However, for most people, and certainly our mountain man wannabe, the latest offerings on the catwalks of Paris and Milan are weird and irrelevant.

The fur trade’s other obsession for the last 45 years has been debating animal welfare vs. rights, and the role of sustainable use as a conservation tool. (That’s how long it’s been since the International Fund for Animal Welfare began campaigning to end the Canadian seal hunt.) Everything worth saying has probably already been said, but the messages need to be reinforced again and again because we are trying to influence people’s fundamental views about man’s place in nature.

However, our mountain man wannabe is decidedly not our target audience. He is no more interested in debating the rights of squirrels than he is in how they look, sheared and dyed pink, around the neck of a supermodel.

What he does want is information that’s educational, useful, and makes him go, “Wow! I never knew that!” He may or may not have a hankering to eat squirrel stew, but he is interested in the process, in how to get the squirrel in the pot in the first place. Which means he might also be interested in knowing:

• Why grey wolf and wolverine fur make the best hood ruffs and jacket linings in the Arctic;

• That a deer, raccoon or beaver conveniently has just enough of the oil called lecithin in its brain to tan its own hide; and

• That mink carcasses make great crab bait, and it’s not because crabs love them so. (Squid are better.) It’s because seals and sea lions can’t stand the smell!

All these and more interesting questions are now addressed in great detail on the web by hunters, trappers, tanners and crab fishermen, and reality TV is cashing in on this treasure trove of amazing information. How about we do the same?

How about we complement our efforts targeting traditional audiences, and spend a little more time talking to people who could be powerful allies if only we started speaking their language?

Let’s connect with all the mountain men out there, not just the ones walking the walk, but also the millions of people tuned in to cable TV, dreaming of making their own squirrel stew some day.

I’ll start the ball rolling. In my next post, learn why one of the most desired and expensive of North American furs in the mid-20th century is now just roadkill.

Why Is Fur So Controversial and Why Should It Matter?

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurWith fur now so prominent on the designer catwalks, in fashion magazines, and on the street, many publications are hosting…

Read More

With fur now so prominent on the designer catwalks, in fashion magazines, and on the street, many publications are hosting debates about the ethics of wearing this noble but much-maligned material. Among all the arguments, for and against, one question is never asked: “Why is fur so controversial?”

True, animals are killed for fur. But more animals are killed for food every day in North America than are used for fur in a year!

But we don’t need fur, you say? Well, PETA and their friends argue that we don’t need to eat meat either.

The real reasons why fur is “controversial” may surprise you.

Let’s take a look ...

10 Top Reasons Why Fur Is “Controversial”

#1. The Fur Debate Is “Class War”: According to “animal-rights” philosophers, eating meat is no more justified than wearing fur. Even Peter Singer - whose book Animal Liberation launched the modern animal-rights movement – wrote that it is hypocritical to protest against the fur trade while most people eat animals daily. In practice, however, fur is an easy target because relatively few people wear it – and most of them are women. And fur apparel is expensive (because much of the work is done by hand) making it easy to dismiss as an “unnecessary luxury”.

Fur is a convenient cross-over issue for those who decry “capitalist exploitation" of both humans and animals. Thus, the “A” in “ALF” (Animal Liberation Front) is often circled – the graffiti code for “Anarchy” – and it is usually left-wing parties in Europe that endorse anti-fur positions.

The fact that those hurt by anti-fur campaigning are working people – aboriginal and other trappers, farm families, craftspeople – is something these “idealists” prefer to ignore. This is why PETA is so upset by the growing popularity of fur for small accessories or trim on parkas: this trend is making fur much more widely accessible, especially for young people.

#2. Fur as Scapegoat: We are bombarded with warnings that human activities are changing our climate, polluting the environment, destroying rainforests and driving record numbers of species into extinction.

These problems are complicated and solving them will require major changes in our lifestyles. So it may seem reasonable to claim that “if we care about nature, at least we should stop killing animals for frivolous products like fur!”

In fact, the trapping of wild furbearers is strictly regulated by state and provincial wildlife agencies to ensure that we use only a small part of the surplus nature produces each year. Endangered species are never used.

The modern fur trade is an excellent example of “the sustainable and responsible use of renewable natural resources”, a key ecological concept supported by all serious conservation authorities (International Union for Conservation of Nature, WWF, UNEP). Using renewable resources, like fur, is ecologically preferable to using synthetics derived from (non-renewable) petro-chemicals. And giving commercial value to wildlife provides a financial incentive to protect natural habitat, which is vital for the survival of wild species.

But why let facts get in the way of a good story?!

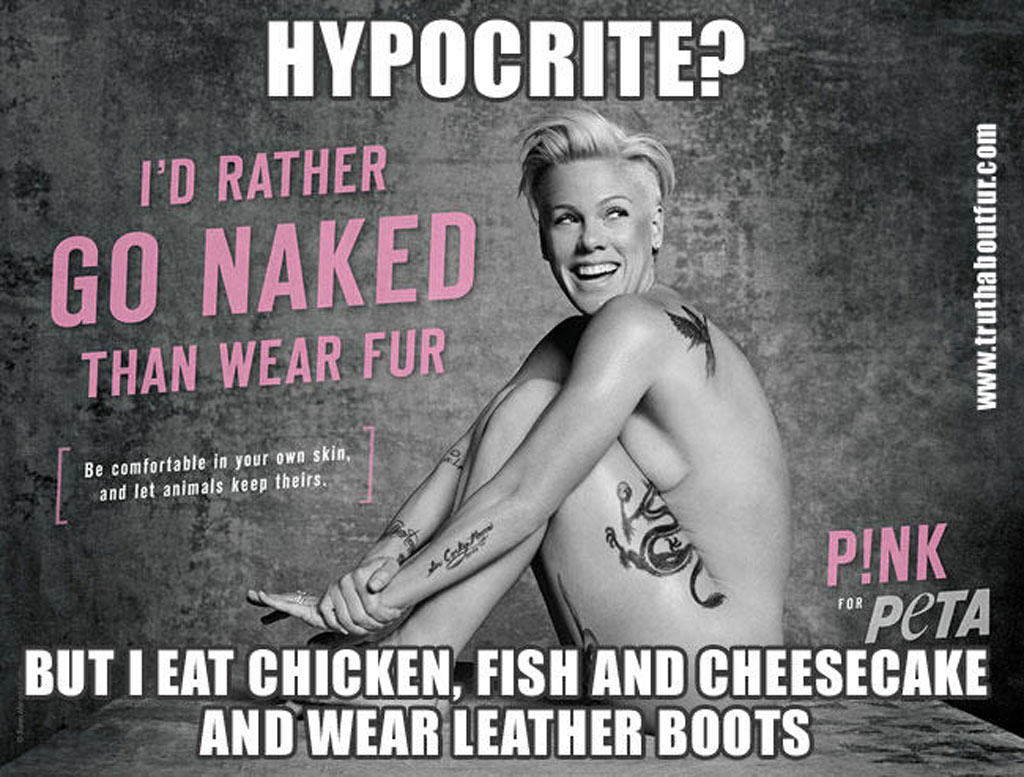

#3. “Media Sluts!” Speaking of stories, PETA co-founder and president Ingrid Newkirk explains its success in using the media to promote its issues (and brand!) as follows: “We’re media sluts ... we didn’t create the rules, we just learned how to play the game!”

PETA understands that media can’t resist running a photo feature about a starlet, supermodel or other "celebrity" – especially if they are female and undressed. So what if these women know nothing about conservation or wildlife biology, “the medium is the message”. Of course, getting on the evening news does not pay the bills. That’s where modern fund-raising technology comes in. (See #4)

#4. Follow the Money! Many people don’t realize that campaigning against fur and other animal-based industries has become a very lucrative business. PETA and its affiliates rake in some $30 million annually; the so-called Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) collects more than $100 million. HSUS execs pull down six-figure salaries. And there are dozens of other groups.

Very little of this money goes to animal shelters; most is churned back into driving more “issues” and fund-raising campaigns.

PETA alone has more than 100 employees writing letters to editors and planning photo ops. The media stunts are quickly followed up with direct-mail, fund-raising appeals: “Please help us to stop this atrocious suffering!”

Computer technology allows this thriving new protest industry to target zip codes most likely to contribute. The money collected far exceeds what the fur trade – an artisanal industry comprised of thousands of small-scale, independent producers – can devote to telling their side of the story. So the activist message is most often heard – creating the impression that “there must be something wrong with the fur trade!”

As a leading animal activist once told me: “You can’t win because you have to spend money to fight us, but we make our money attacking you!”

#5. Fur as Political Football: Lobbying to ban the production or sale of fur is emerging as a favorite activist tactic – especially because they don’t even have to win for it to work!

Political campaigns transform the parochial views of special interest groups into “hard news”. Well-informed journalists may resist providing free publicity for PETA’s street theater, but they cannot easily ignore a political campaign. And legislative bans carry a deeper message: if governments are prepared to shut down a tax-paying business, surely this must be a very evil industry indeed!

In fact, the real message of politics is ... politics.

Political attacks on the fur trade generally succeed only at the municipal level (an incestuous world where very few councillors make the decisions), or in countries with proportional representation. In these countries (including most of Europe), there are so many parties that complex coalitions are needed to cobble together a majority. Mink farmers (or seal hunters) wield limited economic clout – and fewer votes – making them ideal sacrificial lambs to bring left-wing or “green” partners into government coalitions.

Meanwhile, European governments now pay trappers to kill muskrats, (to protect dykes and farmland in Belgium and the Netherlands), or badgers (in Britain, to control bovine tuberculosis) – and destroy the furs. And while the EU banned the import of sealskins, fishermen there can shoot seals to protect their nets, without regulations or oversight, so long as they don’t sell the pelts!

Another revealing example is Israel, where a few members of the Knesset are hoping to ban all fur sales. Because there is almost no fur trade in Israel, it is very tempting for the government to yield to such pressures; there is no domestic downside. A fur ban in Israel would change almost nothing in that country, but activists hope to use it as a precedent for similar initiatives in Europe and North America – a rare example of “progressive” groups citing Israel as an ethical leader!

#6. Nature as Disneyland: Not so long ago, most North Americans still had family on the land. Summers might include visits with grandparents or other relatives on the farm – people who understood that nature is not Disneyland and animals are not talking cartoon characters.

Today, for the first time in human history, most of us live in cities. We have little direct contact with (living) animals that are not pets. We do not know that taking some animals each year may be the best way to keep the rest of the population stable and healthy. Or that wildlife must be controlled to protect property and habitat (e.g., from beaver flooding), to protect nesting birds and their eggs from predators (coyotes, foxes), to prevent the spread of dangerous diseases (e.g., rabies in raccoons, skunks), and for many other reasons.

When our meat comes in Styrofoam trays in the supermarket, we are easily shocked by images of animal slaughter for any purpose. Animal activists complain that industrial/urbanized society has lost respect for nature and animals – but, ironically, their campaigns attack the livelihoods and cultures of the few people who still live close to the land.

#7. Harassment of Women: We are rightfully disgusted when women are attacked in some countries for wearing their skirts too short or not covering their heads. Animal activists, however, have little to learn from religious extremists when it comes to harassing women.

Some notable anti-fur slogans have included: “It Takes 40 Dumb Animals to Make a Fur Coat, But Only One to Wear It!” and “Shame!”, an HSUS campaign showing a woman in fur hiding her face with her handbag. The goal is clearly to intimidate women, to make them feel uncomfortable wearing fur.

One wonders, would anti-fur campaigning have become so aggressive if men wore most of the fur coats? Perhaps PETA would show more moral conviction if they demonstrated against the use of leather by motorcycle gangs!

#8. Politically-Correct Bullies: “If you don’t remove fur from your store, we will picket every day before Christmas with a large-screen TV showing animals being skinned alive!”

When fur represents only a small proportion of their sales, fashion retailers cannot easily resist this sort of threat, even if fur is perfectly legal and their customers want to buy it. Those who persist may find their locks glued or windows broken. Or their homes may be splattered with red paint, their neighborhoods plastered with posters denouncing them as “murderers”. Security costs soon outweigh potential profits – or principles about freedom of choice.

When the mafia targets businesses in this way, it’s called a protection racket. When foreigners use threats of violence to make us do what they want, it’s called terrorism. But retailers targeted by animal activists are on their own; their tormenters are called “idealists”. And if the retailer decides to buy peace, their decision to drop fur is trumpeted by the bullies as a “moral victory” – and more proof that fur is “controversial”.

#9. Seeing Is Believing! Nothing has done more to fuel the fur “controversy” than a number of shocking videos posted on the web. These videos show animals in very bad condition on fur farms and even, in one particularly horrific example, an Asiatic raccoon being skinned while clearly still conscious, in a dusty village square somewhere in China.

Pictures are worth a thousand words and videos don’t lie ... or do they?

The injured animals shown in one “US fox farm” video were actually being kept for urine, to produce hunting lures. The farm never sold fur – fur from such poorly cared-for animals would have little or no value – and was later forced to clean up its act by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. (The video mentions none of this.)

The Asiatic raccoon-skinning video is particularly upsetting, and especially dubious. No one would skin an animal alive. Morality aside, a conscious animal moves, increasing the risk of damaging the fur or cutting the operator. And with the heart still beating, an animal bleeds more, unnecessarily soiling the fur.

The only logical conclusion, shocking as this may be, is that someone paid a poor villager to do this terrible act for the camera.

When this video was first released by a Swiss animal rights group, in 2005, the International Fur Federation requested the full, uncut tape, with information about when and where it was filmed, so an investigation could be launched. There was no response – a strange reaction from a group supposedly concerned about animal welfare. Unless, of course, the real goal was to fuel controversy!

SEE ALSO: 5 REASONS WHY IT'S RIDICULOUS TO CLAIM ANIMALS ARE SKINNED ALIVE

#10. A Culture in Search of Values: Above all, the controversy sparked by fur reflects a confusion of values in our fast-changing society.

Wherever they were from, our grandparents lived in cultures with very clear ideas about what we should eat or wear, how we should speak or act. Urbanization, globalization, secularism and multi-culturalism have changed all that. It is no longer always clear what is right or wrong.

Without a social consensus, we live in constant doubt; sects flourish, politics become increasingly polarized, conspiracy theories abound. A simple trip to the grocery store becomes an existential experience: Should we eat meat? Is it better to buy organic or locally-produced food? What about low salt, high carbs, GMOs?

In this cloud of nutritional, ecological and ethical confusion, fur can become a flashpoint for the clash of urban and rural cultures, for troubling questions about our relationship with nature and animals, and, not least important, for the tension between collective values and individual freedom of choice.

Final Word – Fur Leaves No One Indifferent!

Fur means different things in different cultures. Aboriginal people believed they could partake of animal power by wearing fur and that using these “gifts” showed respect for the animals that gave themselves so that humans might survive. (Much like many of us still say grace before meals.) Furs have also often conveyed status and power: furs adorn ceremonial robes and, in the Middle Ages, strict laws determined which furs might be worn by different classes. Ultra-Orthodox Jews wear fur-trimmed hats (streimels) on the Sabbath, to spiritually elevate both man and animal.

In the golden years of Hollywood, furs represented luxury and sensuality – as they still do for many. Today, animal activists would like to associate the wearing of fur with human arrogance and guilt, even as a new generation of designers rediscovers its natural beauty and makes fur more versatile and accessible than ever before. While some now denounce the fur trade as a crime against nature, others argue quite the contrary, i.e., that wearing and admiring fur can remind modern city dwellers that we are, ultimately, dependent on nature for our survival.

And this, perhaps, is the true nut of the fur debate: are humans “a rogue species”, “a cancer on the planet” that would be better eliminated, as some “deep ecologists” and the “voluntary human extinction movement” would have us believe? Or are we truly part of nature, a natural predator with as much right to be here as any other species (although with greater responsibilities, because of our unprecedented power and knowledge)?

Fur, in summary, has always been more than a beautiful, natural material. Fur has always had symbolic meaning, a powerful hold on the human imagination. The current “controversy” about fur is just the latest example of the on-going attraction of the most precious of natural clothing materials.