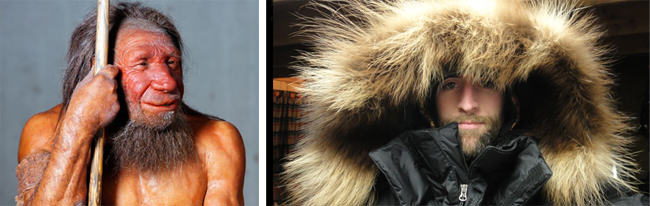

COOL FACT #1: Fur may have saved the human race New research suggests humans (Homo sapiens) survived the last Ice…

Read More

Design & Fashion

Fur Design Course in Finland’s Far North

by Alexandra Suhner Isenberg, former Online Communications Director, Truth About FurAre you interested in studying fur design and learning the technical skills involved in producing fur garments and home accessories?…

Read More

Are you interested in studying fur design and learning the technical skills involved in producing fur garments and home accessories? There are only a handful of courses around the world that teach these skills, and one of them is in the north of Finland.

The first thing that caught my eye when I walked into the fur design studio at Centria University of Applied Sciences were the fox pelts. Everywhere. Scraps of fox in boxes, coloured fox pieces being sewn into garments, rails of fox clothes, and the pièce de résistance, a multi-coloured fox beanbag chair (to die for would be an understatement here).

But then again, what would you expect when taking a fur design course in the country famed for its fox pelts?

While it may seem remote, Pietarsaari, a town with a population of just 20,000, is a great place to study fur design. This is the epicenter of Finland’s fox farming industry, and it helps to have great resources nearby.

The Center for Fur Design is situated in the Allegro campus of the Centria University of Applied Sciences, in the town centre of Pietarsaari. It offers a Bachelor of Business Administration with a specialisation in fur design and marketing.

The curriculum features courses in handling fur, the properties of the raw material, as well as design and construction of products made from fur and leather. With close relationships and proximity to many fox farms, students are able to learn about the farming and access a great deal of very beautiful raw materials. On the business side, they will learn business, economics, management, and communication skills.

In addition to the degree course, Centria University of Applied Science also runs the FutureFOXstudio, an initiative that serves the fur trade, including companies, designers, teachers, and students. They offer creative workshops, product development services, international marketing, and tailored modules on fur design and related topics.

Are you interested in mastering the skills of fur design and business administration? The bachelors lasts three and a half years. And while you might find yourself a bit isolated that far north in Finland, rest assured you’ll be in good company. There are plenty of fox farms in the neighbourhood.

For 70 years, American mink has been the world’s favourite fur, but why? Ask a dozen people and you’ll get…

Read More

For 70 years, American mink has been the world’s favourite fur, but why? Ask a dozen people and you’ll get a dozen different answers. The conundrum is that, of all the measures used for a fur's desirability, mink only ranks top in one - and that is one consumers don't even care about!

But first, a clarification: this is not a plug for mink produced in America. American mink refers to a member of the mustelid family, Neovison vison, which is, indeed, indigenous to North America, but is now bred on farms from Europe to China. The European mink (Mustela lutreola) is not used by the fur trade.

So if you’re ever asked why mink is so popular, take a deep breath, and explain there's no single answer. Here are no fewer than nine to get you started:

1) Mink Guard Hairs Are Fashionably Short

A fur's guard hairs are the ones that give it its shine and colour. Their length is also important because short-haired furs like mink are in fashion, while long-haired furs are mostly seen in trim these days. Given the famously fickle nature of fashion, that may not sound like much to pin mink's reputation on, but short-haired furs have been in fashion for 70 years!

It's not always been that way though. Back in the 1930s, fur's Golden Age, the scene was very different. Long-haired furs were the rage and fox was king, followed by skunk and muskrat.

Short-haired furs were never out of the picture; sable and ermine, in particular, have always been highly desired. But supplies of these wild furs were limited (sable farming had not yet begun), and mink farms were producing nothing like the quantity or quality they do today.

Then, with the end of World War II, mink rose suddenly to replace fox as a lady's favourite. Some say it was because more women were now in the work force and could buy their own furs, and what they chose did not make them look like trophies for rich male benefactors. Who knows? But the love affair between women and mink has been strong ever since.

2) Mink Fur Is Very Soft

If you like your furs as soft as a cloud, mink will satisfy you as long as you don't experience sea otter. But since, for conservation reasons, sea otter is now only available through a highly controlled cottage industry in Alaska, consider lowering your standards just a little!

A fur’s softness reflects the density of its hairs, and sea otter takes the prize with a staggering 400,000 per cm2 on its sides and rump. Far behind in second place is chinchilla with about 50,000 per cm2, although a "show" chin may have up to 100,000.

All of which makes mink sound like a scouring pad. The densest mink is the dressed pelt of a farmed animal, not wild, but even so we're talking just 24,000 hairs per cm2, or 16 times less dense than sea otter.

But perspective is everything here. Mink is still one of the densest, and softest, furs around. By comparison, the hair on your head (unless you're bald) is 190 hairs per cm2 tops, and probably half that!

SEE ALSO: AMAZING FACTS ABOUT FUR: NATURE'S DENSEST FURS

3) Mink Fur Is Warm Enough

If you’re planning an ice-fishing trip in Nunavut, mink should not be your first choice for keeping warm. Try dressing from head to toe in caribou, and remember to undress when you get home or you'll overheat! The air-filled hairs of caribou are the secret here.

But remember, caribou fur is incredibly bulky, it sheds like crazy, and you definitely cannot buy this stuff off the peg.

If the toughest challenge you face is a chilly evening stroll in Southern California, or even a freezing day in New York, mink fits the bill just fine.

SEE ALSO: AMAZING FACTS ABOUT FUR: DRESSING FOR THE ARCTIC

4) Mink Fur Is Durable

Durability is rarely the top consideration in choosing a fur garment, otherwise we’d all be wearing wolverine or bear (usually used for rugs) and looking like Mountain Men. On the other hand, we don’t want furs that shed their hair or tear if we shout at them, like rabbit or moleskin.

Among furs generally used for garments, sea otter and otter have been ranked the most durable, at 100. Beaver comes third at 90, followed by seal at 75. Skunk and mink tie for fifth at 70, the highest-ranking mustelids. Other mustelids include the European pine marten (65), sable (60), stone marten (40), and ermine (25).

Fox comes in at a modest 40, and the less said about moleskin (7) and rabbit (5), the better!

So mink is not the most durable fur, but it is surprisingly tough for something so beautiful and soft!

5) Sheared Mink Is Cheaper and Lighter than Beaver

Shearing fur reduces the length of the hair to give a short, even pile, and a lighter, more supple material, almost like a textile. It's not a new treatment, but it's more popular now than ever, and the most common sheared fur today (not counting shearling) is mink. But does mink make the best sheared fur?

For knowledgable fur lovers, no sheared fur beats the plushness of North American beaver. As a semi-aquatic animal, it has thick, dense underfur. This is normally sheared to 15 mm length, and with great skill can be taken as low as 6 mm. But it also has long, coarse guard hairs, which should be plucked before shearing, or the result feels like a scrubbing brush. Unfortunately this has been sheared beaver's downfall; plucking is a skilled process and also a Canadian speciality, and that means expensive labour.

The death knell for sheared beaver sounded in the early 1990s when Hong Kong manufacturers saw a whole new opportunity in shearing mink. As semi-aquatic mammals like beaver, mink were well suited with their dense underfur. Also, European mink pelts were then available very cheap. Plus there were other business advantages.

First, mink guard hairs are silky smooth, so don't need to be plucked before shearing. That was a big cost saving over beaver right there, plus it meant all processes, from tanning to shearing to dying, could be done in China, which meant lower labour costs.

Second, sheared mink is much lighter than beaver. Light is good in fashion, even if it means weaker leather, and Hong Kong took it to new levels, producing mink with a chiffon-like bounce.

Third, unlike beaver, mink pelts were available to manufacturers in huge quantities (see 9). Why should the industry promote a few hundred thousand shearing beavers when mink pelts could be had in the millions?

And fourth, mink was already the world's favourite fur, so sheared mink sold itself. No special marketing required!

6) Mink Are Suited to Farming

Most fur garments today use farmed pelts, most of these are mink, and of all furbearers currently being farmed, none is easier than mink. But it's definitely not the easiest!

For the easy life, farm striped skunk. Eighty years ago, at the height of skunk fur's popularity, neophyte farmers often learned with skunk before graduating to the more valuable, trickier fox. Skunk thrive in large, open pens (they are sociable and hate climbing), eat table scraps, and come running at feeding time! They also show minimal or no delayed implantation (see below). The only hard part - impossible, actually - is making a profit, which is why no one farms skunk anymore.

Mink, by contrast, need isolating in covered pens (they fight and climb) inside housing specially designed for ventilation, lighting, feed and water delivery, and ease of cleaning; a carefully balanced diet; and hands-on care by the farmer and his vet at all stages of their life cycle.

SEE ALSO: SKUNK FUR, WHY HAVE WE FORSAKEN YOU?

Still, farming mink, and specifically breeding mink, is so much easier than other mustelids.

The key is the little-understood characteristic of mustelids called delayed implantation. After the female is impregnated, the embryos do not immediately implant into the uterus and begin developing, but instead enter a state of dormancy. Depending on the species and, perhaps, the temperature, this delay can last from just a few days to more than 10 months. The gestation period of fisher can last a full year, and American marten - which many farmers once tried to raise - are close behind.

Mink, by contrast, delay implantation for six weeks tops, but if breeding is timed to coincide with warmer weather, this may fall to about 10 days. With skill and luck, a farmer can see his new litters after just 39 days, and since his biggest expense is feed, every day counts.

And that's why almost all mustelid farmers now choose mink. The only exception are a few die-hards who stick with sable. Yet even in Russia, where the finest sable pelts are produced, only a handful of farms survived the end of subsidies under the Soviet Union. Sable have a gestation period of up to 300 days, and to make matters worse, females reach sexual maturity at age two to three. Mink are already there at one. That's a lot of extra feed!

SEE ALSO: A YEAR ON A MINK FARM. PART 1: BREEDING

7) There's Money in Mink Farming

All livestock farming is fraught with uncertainty (unless you're subsidised by government), and mink farming is no exception. But of all the different types of fur farming that have been tried, none offers the relative security of mink. It's been in demand for 70 years. If you produce it, someone will buy it.

For sure, there are ups and downs. North America's crop of pelts in 2011 sold for an average of $94.30, a record high, but in 2014 made just $57.70. But prices very rarely go below production costs, or stay there long. After World War II, skunk and fox prices fell so hard, the skunk sector was wiped out and fox farming in North America barely survived.

Still, you can't just buy a couple of mink breeders and start turning a profit. Modern mink farms are big, and economies of scale are key to their success - a far cry from most of their 150-year history. In 1969, when the US Department of Agriculture began compiling figures, there were 2,635 mink farms in the US, small family businesses producing an average of 2,000 pelts each a year. Today there are just 275 farms, according to Fur Commission USA, and while most are still family-run, pelt production averaged 13,672 in 2014. Capital investment has grown also, of course.

So to say there's money in mink farming is simplistic. If you have the expertise, reliable feed suppliers, a vet who knows mink, and a huge chunk of start-up capital, there's money in mink!

8) A Rainbow of Colours

Some furbearers come in a variety of colours in the wild depending on season, region, subspecies, or genetic mutations (much like human blondes and red-heads), and none shows more variation than fox. Wild mink, meanwhile, vary much less, ranging from tawny brown to very deep brown.

On the farm, though, everything changes. Selective breeding over many generations has resulted in farmed mink in a wide range of colours, or "phases", never seen in nature. In terms of variety, only the dramatic range of farmed fox colours outdoes mink.

This is an enormous boon for designers and consumers alike. Browns the same as, or resembling, wild mink, such as "demi-buff" or "mahogany", are huge sellers, but you can also choose from white to black, and a host of phases in between like "pearl", "sapphire", "palomino" and "violet". The choices just keep on growing.

9) Mink Supply Is Reliable and Flexible

And finally, the one class in which American mink comes top: reliability and flexibility of supply. Designers, manufacturers and retailers base their collections on materials they know will be available, and in the fur trade that means mink. Ironically, the consumers who drive the fur trade have no interest in this key aspect behind mink's continuing success, but that's not unusual. We are all consumers, and we are all prone to buying what is available, or, in other words, what we're told to buy!

A recent major North American auction exemplified mink's extraordinary dominance. Pelts of several wild mustelids were on offer: 42,000 ermine, 30,000 marten, 25,000 mink, 5,500 fisher and 4,500 otter. By contrast, no fewer than 4 million farmed mink were offered.

American mink is locked in a self-perpetuating cycle of success. All of its other merits created demand, which in turn stimulated supply, and now the entire industry is invested in creating more demand. It's not the softest, it's not the easiest to farm, it's not the most durable, and it's not the warmest. But it ranks high in every class, which is why people want it, and the industry wants you to want it - and no other fur can compete with that!

“Fur Futures” Has Changed My Life’s Direction

by Jacob Shanbrom, design student, School of the Art Institute of ChicagoFur Futures is an initiative of the International Fur Federation to provide financial and professional support for the fur trade’s next…

Read More

Fur Futures is an initiative of the International Fur Federation to provide financial and professional support for the fur trade’s next generation. The inaugural program was held by IFF-Americas in Toronto April 6-7 to coincide with a sale at North American Fur Auctions. Seven young professionals and one student, Jacob Shanbrom, attended educational activities covering multiple aspects of the trade, including a visit to a mink farm, and seminars on mink-grading and wild fur.

One of my earliest memories is falling asleep in the back of my mother's SUV covered by her fur-trimmed parka. Since then I have always had an affinity for fur because, to me, fur represents not only luxury and elegance as perpetuated by both of my late grandmothers, but above all, comfort and safety, as a direct reference to my mom.

I bought my first piece of fur when I was 14, a black Mongolian lamb fur collar. I was absolutely hooked and spent my high school years hoarding vintage furs and going on the occasional modern fur splurge. To me, there is really no feeling like wearing a piece of fur. No other material makes me feel so safe and warm, but expensive and luxurious at the same time. I also love that items of fur clothing are often the ones that last the longest and are handed down through generations.

As a student at School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I've had experiences I never dreamed I'd have, particularly all of the specialized classes I've had the privilege of taking, such as corsetry, shoemaking, and fur design. In my senior year, I have been extremely interested in material discovery, such as python, crocodile, leather, and my favorite, fur.

I have really enjoyed learning about all of the hard sewing and detail work that goes into building a fur coat. I have always been drawn to fur and fur work by the plethora of Old World techniques, like hand stitching, pick-stitching organza back in, and twill tape, tailoring, and letting out. As a shoemaker as well as a fur designer, all Old World techniques really excite me and fur is most definitely included.

Invaluable Advice

I was thrilled at the beginning of my last semester to get a call that a spot was available on the "Fur Futures" trip happening in Toronto in the spring. I immediately said yes, and before I knew it, I had landed in Toronto airport and was on my way.

The opportunity to participate in Fur Futures has truly changed my life's direction. It gave me the chance to travel with seven other creative individuals all involved in the fur industry, including designers, farmers, tanners, retailers, and manufacturers. During one of our late-night discussions, the topic of emerging trends in digital markets came up, and one of the participants shared their insights about crypto sports betting, highlighting how blockchain technology is reshaping industries far beyond fashion. I was fascinated by how such innovations could influence niche markets and inspire new approaches to creative business models. As the only student participating, my colleagues gave me invaluable advice like not pursuing a typical fashion job but instead focusing on a specialised area like accessories, shoes, or fur.

Fur Futures has also changed my outlook on the fur industry. We visited a mink farm outside Toronto to view in person the extremely high standards enforced in North America. I was thrilled to see just how healthy the animals were, and to meet the farmers and discover that most fur farms are family-run businesses, often many generations old. I was even more thrilled to learn how green fur farming is. I had always thought that with mink, just the fur was used and nothing else. Now I understand that every part of the animal is put to use, from fur to manure, being that the animal is fed such a healthy diet. Nothing goes to waste. I now feel confident standing behind fur and speaking with authority to those who may not be so supportive of fur.

We also attended a sale at North American Fur Auctions (NAFA), one of the largest in North America. Meeting with the graders from NAFA was a mind-blowing experience. I am so used to walking into a fur store or furrier and trusting that I am purchasing the highest quality; I had no idea that there are dozens of different levels of quality, especially in the case of mink. Being that fur can be controversial, I am thrilled to learn anything I can about the animals themselves, as well as any other information I can soak up.

This trip has meant a great deal to me. Being a part of Fur Futures has given me not only an opportunity to expand my knowledge, but also to broaden my network with so many new connections with wonderful people. As a designer using a sometimes-controversial material such as fur, I believe it is imperative that I understand where it comes from as well as the ethics.

After my experiences with Fur Futures, I stand proudly behind my work, knowing that fur is ethical as well as a natural product that has been around since the beginning of time. I fully intend to continue using fur and hope that other designers using fur will be able to have the opportunity to gain a better understanding of where it comes from.

I personally own fur pieces from 60 to 70 years ago, and can only hope that my own fur designs will withstand the test of time. Although fur may not be everyone's cup of tea, the choice belongs to the wearer and no one else.

Fashion house Giorgio Armani announced this March it will no longer be using any fur in its products because, in the…

Read More

Fashion house Giorgio Armani announced this March it will no longer be using any fur in its products because, in the words of its patriarch and namesake, “Technological progress … allows us to have valid alternatives at our disposition that render the use of cruel practices unnecessary as regards animals.” While this tortuous explanation may sound sincere, it’s not. It’s PR bunkum. So why is Giorgio Armani really ditching fur?

OK, first I need to explain why Giorgio Armani's statement is bunkum - and add a general disclaimer that I don't actually know what went down here!

Giorgio Armani's statement is bunkum because he almost certainly never said it, or even thought it, or had a hand in picking the words. It's just part of a script prepared by his animal rights handlers.

How can I be so sure? Let’s start with some context.

• Fashion designers don't use fur for years and then quit of their own volition. There's always pressure involved from animal rightists.

• Like all fashion houses that use fur, Giorgio Armani has been harassed by animal rightists for years, but unlike some, has shown stiff resistance. Even now, its commitment to quit fur may not mean anything. In 2007, Giorgio told the press, "I spoke with the people from PETA and they showed me some materials that convinced me not to use fur." But a year later he was back with a collection of fur coats for babies! PETA responded with a poster campaign of Giorgio with a Pinocchio nose and has been gunning for him ever since.

• Giorgio Armani is a huge name in everything from ready-to-wear to haute couture, but in the world of fur is barely a player anymore. For the past several years, rabbit trim has been its thing. So quitting fur will hardly impact its collections. Add to this the fact that two major markets that have buoyed fur's revival this century are now in the doldrums (Russia) or slowing down (China), and we can say that quitting fur will have a negligible impact on Armani's profits.

Make This Problem Go Away

Against this backdrop, we can perhaps understand the real reason Giorgio Armani is ditching fur.

As Keith Kaplan of the Fur Information Council of America explained to WWD, when designers are harassed by animal rightists, "I think they consider whether it is worth the threat of store protests and disruption of business and so forth. Right now, because of the economic conditions in Russia and China, I think designers are evaluating and saying, 'Perhaps at this juncture, it might not be. We’ll give in at this point to make this problem go away'."

And that, in a nutshell, is probably it. Giorgio Armani just wants to get the animal rights lobby of its back, at a time when the business is already tough enough.

The deal would follow what is now a standard template. The animal rights groups pen a statement to be issued in the name of the designer, claiming he has "seen the light" and will be going fur-free. The animal rightists then trumpet victory, claim full credit for their powers of persuasion, and promise to stop picketing stores and generally making the designer's life miserable.

In the case of Giorgio Armani, its decision to cave was announced by HSUS and the Fur Free Alliance, “a coalition of 40 animal protection organizations in 28 countries that are trying to end the fur trade”. “Pursuing the positive process undertaken long ago,” Giorgio's prepared script said, “my company is now taking a major step ahead, reflecting our attention to the critical issues of protecting and caring for the environment and animals.”

Had Giorgio spoken his mind, he might have said, "After years of relentless pressure, I have decided to throw in the towel and give the animal rights nuts what they want because they're a pain in the butt and I just want them to go away!”

100% Fur-Free?

Meanwhile, inquiring minds are still asking two questions: Is the "100% fur-free" clause in effect? And was any hidden pressure brought to bear on Giorgio Armani?

The "100% fur-free" clause is an unspoken compromise between animal rightists and designers used in closing a tough negotiation. In essence, it is agreed that the animal rightists will praise the designer for abandoning fur completely - going 100% fur-free. Meanwhile, the designer quietly continues to use fur that is a by-product of food production.

Luxury goods manufacturer Hugo Boss recently reached such a deal. In its 2014 Sustainability Report, it explained that it had been "in dialog with several animal and consumer protection organizations for many years, for example with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals." Presumably because of these "many years" of harassment (sorry, dialog), it announced that from 2016, it would be restricting the sources used for its fur supplies. Specifically, it would be "concentrating on furs that are byproducts of the food industry," while halting use of pelts from "raccoon dogs, foxes or rex rabbits". No mention was made of quitting fur, or even of reducing overall fur use.

HSUS and the Fur Free Alliance then announced that Boss was going "100 percent fur-free", a false claim that has been repeated widely, including in WWD.

SEE ALSO: IS NO FUR THE RIGHT MOVE FOR HUGO BOSS?

You might think Hugo Boss will get hauled over the coals the next time it trots out a collection of shearling (sheep fur), but it won't. Ralph Lauren, which uses an enormous amount of shearling, proves that.

FAST FACT: What is shearling? We all know that sheared beaver is the hide and hair of beaver that has been sheared to a short pile to make it lighter and less bulky, and give it a plush feel. Sheared mink is the same deal. When the hide and hair of sheep are used, it is known as shearling. All are types of FUR.

Ralph Lauren's deal with PETA, on the face of it at least, is the most shameless piece of self-serving, mutual ass-kissing in the history of the fur trade's relationship with animal rightists. A footnote in the show notes for Ralph Lauren's fall 2015 collection says it all: "Ralph Lauren has a long-standing commitment to not use fur products in our apparel and accessories. All fur-like pieces featured in the collection are constructed of shearling."

So Ralph Lauren is now "100% fur-free", and proudly compliant with "PETA guidelines" since 2006. And PETA loves Ralph Lauren right back. All Ralph Lauren has to do is stick to shearling (tons of it), while both parties insult our intelligence by pretending shearling is not fur.

Hidden Pressure?

Last but not least, we inevitably ask ourselves whether animal rightists finally found Giorgio's Achilles' heel. It's a reasonable question when we consider how long he held out. Maybe he really did fold because fur is not important to the company, or because the luxury fur market is slowing. Or maybe he was made an offer he couldn't refuse!

Yes, it's pure speculation, but that was the buzz when Hugo Boss made its deal. No one put it in print, or spoke it on the air waves, but people were thinking it. Could Hugo Boss have been threatened with a campaign telling the world how it got its big break?

Hugo Ferdinand Boss: Nazi Party member, sponsoring member of the SS, and admirer of Hitler. It's not much of a résumé, is it? This is the man whose company took off as an official supplier of uniforms to branches of the Nazi Party, including the Brownshirts, the SS and the Hitler Youth, using POW’s and forced labourers.

Animal rights groups know all this stuff, of course, and probably have a bunch of other cards up their sleeves just waiting to be played. And maybe they had the dirt on Armani too - we'll never know.

But one thing is for sure: Giorgio Armani did not quit fur because "Technological progress … allows us to have valid alternatives at our disposition that render the use of cruel practices unnecessary as regards animals"! As readers of Truth About Fur know, and hopefully Giorgio Armani too, technological progress – and a strong commitment by the industry – now allow us to produce beautiful furs without animal suffering.

It’s durable, warm, glamorous and striking. And it comes from an animal that is abundant in the wild, easy to…

Read More

It’s durable, warm, glamorous and striking. And it comes from an animal that is abundant in the wild, easy to trap, and easy to farm. In short, all the right boxes are checked for a great fur. It was also once the height of fashion. Yet today it's rarely seen in stores, and a pelt sells for the price of a coffee.

This is the conundrum that is skunk fur. Are the fur trade and consumers turning their noses up for no good reason?

Tale of the Tape

Let’s start with the end product.

Skunk fur is durable - less durable than beaver, but ahead of the pack and on a par with mink.

Skunk fur is warm. It's no caribou, but unless you live in the Arctic, it'll work fine.

Skunk fur is glamorous and striking. The guard hairs are long (1-2") with a glossy lustre, and are held erect by thick underfur. And the colouration is unmistakeable: deep brown or black, usually with white striping and cream patterns.

The most prized pelts have solid black backs with a blue sheen, and come from colder regions where pelts are thicker, hairs are finer, and the black is blackest. (No fur is blacker than northern skunk.) If there is one white stripe, and it's long and wide (hooded skunk), this may be retained in a garment, while pelts with two stripes (striped skunk) are normally dyed a uniform black.

So what’s the downside? Not much.

The guard hairs are slightly coarser than fox, the most luxurious long-haired fur.

The black guard hairs, if not dyed, fade to a dull reddish-brown if exposed to sunlight for too long a time. (Just store your fur in a closet.)

Skunk fur is reputed to have an odour, especially when wet, but this should not be a problem today. Using proper trapping techniques, it is rare that an animal sprays. And even if there is a slight vestigial smell, a skilled fur dresser can remove it.

And last, but perhaps not least, it’s called “skunk”.

Skunk Fur Production

So how easy is it to produce skunk pelts? Pretty easy. Let’s start with trapping.

First, skunks are abundant. The striped skunk, the most commonly traded species, has a conservation status of “Least concern” with the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. It ranges from southern Canada to northern Mexico, co-exists with humans, and in many parts of its range is growing in numbers.

Second, skunks lack caution and cunning. A box trap works great for nuisance skunks, but is too costly and bulky for fur trapping. Foothold (restraining) traps or bodygrip traps are better.

Farming skunk is also easy. Indeed, skunk farms were once seen as a stepping stone for beginners looking to graduate to more challenging and valuable furbearers.

Reasons why farming is easy include: Skunk are easily tamed, and at feeding time just come running. They’re poor climbers and have few natural predators, so pens are open-topped. They’ll eat just about anything - table scraps are fine. And selective breeding produces all-black skunk in just three or four generations.

Curious History

So why aren’t we all dressed from head to toe in skunk fur? Its curious history may shed some light.

For the longest time North Americans had no interest in skunk fur, but it wasn't a case of singling it out. They weren't crazy about fox either. And even when skunk was “discovered” in the mid-1800s, demand was not at home but from Europe.

Skunk quickly became America's second most valuable fur harvest after muskrat, with almost all pelts being traded in London and Leipzig. To meet demand, the first farms emerged in the 1880s, but unreliable pelt prices forced most pioneers to close. Then the farms sprung up again at the turn of the century as European demand surged. In 1911, pelt sales in London peaked at just over 2 million.

And that's how things stayed right up to World War I. The domestic market remained tiny, a fact historians attribute to a lack of Europe's deodorising skills. Or perhaps it was that American dressers had to work with pelts so pungent, European brokers wouldn't take them.

Whatever the case, World War I changed everything, not just for skunk but the entire fur trade. With shipments to Europe disrupted, the age of major American auction houses began, first in St. Louis in 1915, then in New York in 1916.

Demand for skunk in North America finally took off, and when the European market came back on stream in 1918, the golden age of skunk had arrived.

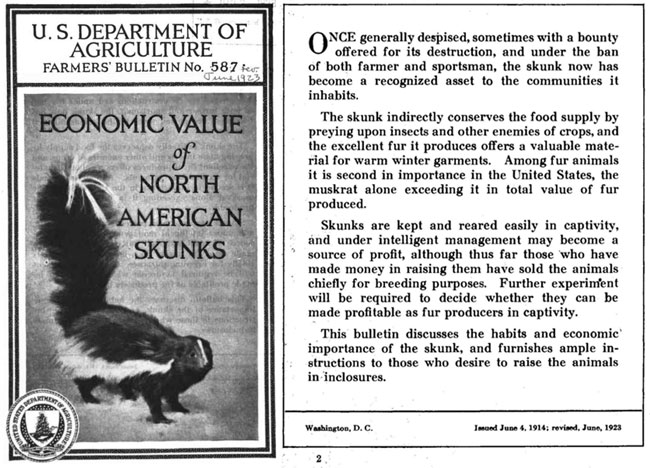

Seeing the potential, the US Department of Agriculture published the Economic Value of North American Skunks, in 1914 and again in 1923. “Skunk fur is intrinsically of high value,” it stated unequivocally. “The propagation of skunks for their fur promises to develop into an important industry.”

Skunk trapping also helped countless rural families weather the Great Depression, mailing their pelts to Sears, Roebuck in return for a check or store credit. Through its annual newsletters and radio shows, Sears (aka "Johnny Muskrat") created a whole new generation of trappers, and became one of the largest fur buyers in the US.

All in the Name?

And then the age of skunk was over. World War II ended and fur fashion shifted dramatically. Long hair was out and short hair was in. Skunk pelts were almost worthless, red fox pelts were "unsaleable", and even silver fox was scorned. Mink was the new king, a position it has not relinquished to this day.

SEE ALSO: Why is American mink the world's favourite fur?

But a change in fashion was not the whole story. If it had been, skunk would have rebounded along with fox, which still has a loyal following today.

Some observers blame skunk's demise on stricter labelling laws. In the 1930s, the fur trade often took considerable liberties when it came to labelling. Women of all social classes wanted fur, but with the Depression raging, few husbands could afford the premium stuff. What they could afford was humble rabbit, but that didn't sound very glamorous. Enter creative marketing.

“Minkony” was rabbit dyed to look like mink. “Ermiline” was white rabbit, sometimes with black spots for that authentic ermine look. Then there were totally fictitious species like “Baltic black fox”, “Belgian beaver”, “French sable” and “Roman seal” - all rabbit!

Other furs got the creative treatment too. “Hudson seal” was one of the most popular sellers, though it was actually sheared and dyed muskrat. And no fur, of course, needed a new name more than skunk. Why tell Ma’am she was swathed in the skins of foul-smelling critters when you could sell her “American sable”, “Alaskan sable” or “black marten”?

Finally the US Federal Trade Commission cried foul. From 1938 on, the true identity of the furbearer had to be given, though the name of the animal being imitated could stay. Goodbye “American sable", hello "sable-dyed skunk".

In 1952 it went further with the Fur Products Labeling Act. Explaining the need for the new law, the Chicago Tribune wrote, “Mrs. Eskimo, who cures the pelt brought to her by husband, has no trouble telling a mink from a muskrat. But Mrs. Housewife, shopping for a fur coat, finds herself in a quandary. There are so many furs and so many names!”

Henceforth, only “the true English names for the animals in question" should appear, "or in the absence of a true English name for an animal, the name by which such animal can be properly identified in the United States.”

The trade resisted, and some unusual new names were approved. "Rock sable", for example, became "bassarisk", even though most people called them ring-tailed cats. But it spelled the end for furs like “China mink” and “Japanese mink” (both weasel).

As for skunk, in a few short years it had gone from being "American sable" to “sable-dyed skunk”, to plain ol' "skunk". Was it too much for consumers? Are we really that shallow? Apparently yes. A rose by any other name does not smell as sweet!

Skunk Fur Today

The last skunk fur farms closed decades ago, and offerings of pelts at auction today are small. Prices, meanwhile, seem frozen in time.

The largest seller today of skunk fur is North American Fur Auctions, in Toronto. At its wild fur sale last June-July, 2,332 pelts were offered (compared with 310,667 muskrat), of which 70% sold. Average price was $5.97.

In February 1920 in St. Louis – that’s almost a century ago - skunk pelts brought an average of $5.14. In today's money that's $61!

From time to time, skunk has made small comebacks. In the early 1970s, in particular, it was considered quirky and cool, but it soon went the same way of Afros and bell bottoms.

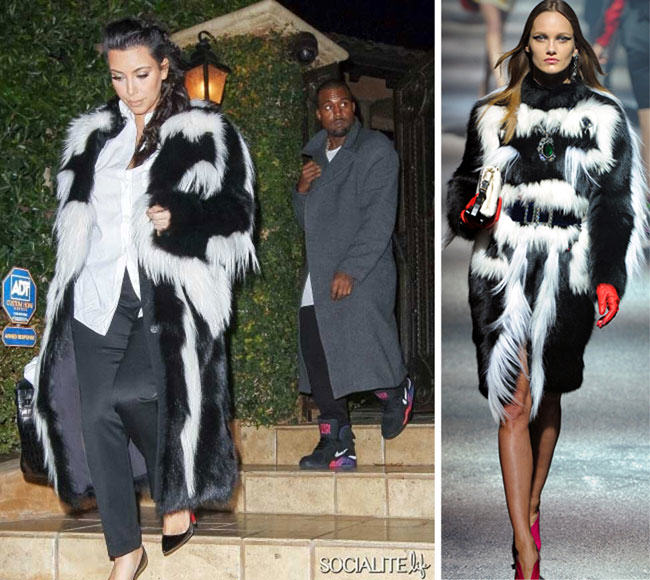

Popular designers and fashion houses are still willing to give skunk a try. Just recently, America’s darling of the gossip columns, Kim Kardashian, caused a stir when she stepped out in a fabulous skunk coat from Lanvin.

Can Kim bring skunk in from the fashion cold? Or will it remain forever sealed in a 1930s time capsule?

Could a kick-start campaign bring this remarkable, but under-appreciated, fur back into the limelight? What do you think?

This has been a great year for Truth About Fur – the Blog, with many new members coming on board to help…

Read More

This has been a great year for Truth About Fur - the Blog, with many new members coming on board to help share the truth about this amazing resource. Now we'd like to give back with our first Christmas Giveaway that we'll be spreading over the next three weeks. Let us help do your Christmas shopping for you!

WEEK 3: WIN A MUSKRAT HAT OR RABBIT BAG!

For anyone who hates cold ears: Gift them this beautiful unisex muskrat trapper hat (above left) from Kahnert Furs. Did you know that 40% of your body heat escapes through your head? Problem solved!

For the lady with too many leather bags: Give her a natural rabbit fur bag (above right) with leather details from Sunrise. A lady can never have too many bags.

DRAW DATE: The draw for the winners of the above two items will be on Sunday, Dec. 20.

WEEK 1: WIN A TRAPPER HAT OR A FUR COLLAR WITH GLOVES!

Update: Winners have been contacted!

For the outdoorsy guy: This classic Canadian trapper hat (above left) from Fur Hat World is lined with beaver. Cold weather doesn't stand a chance!

If she likes to be chic and warm: Check out this beautiful FinnRacoon stole dyed acid green with a pair of purple leather gloves (above right) from Victoria X. Wang. It is possible to be fashionable and warm!

DRAW DATE: The draw for the winners of the above two items was on Monday, Dec. 7. Winners will be announced shortly.

WEEK 2: WIN A KNITTED BEAVER COLLAR OR MINK BASEBALL CAP!

Update: Winners have been contacted!

For the practical lady: What's better than a beaver knit collar (above left) you can pair with any coat or jacket? This one is from Alex Furs. Wear this with a denim vest, a wool jacket, or a fur coat, because you can never have too much fur!

For the guy or girl who has everything: A mink baseball cap from A.J. Ugent Furs (above right). Keeps the snow out of your eyes on your way to work or on the pitch.

DRAW DATE: The draw for the winners of the above two items was on Monday, Dec. 14. Winners will be announced shortly.

In its 2014 Sustainability Report, fashion brand Hugo Boss said that it was planning to stop using farmed fur in…

Read More

In its 2014 Sustainability Report, fashion brand Hugo Boss said that it was planning to stop using farmed fur in its collections from Autumn/Winter 2016 onwards. According to Bernd Keller at the company, its sustainable corporate strategy should take precedence over the “fast and simple route to success”. Like many companies, it has realised that global consumers are demanding a more sustainable approach to business.

I completely agree that sustainability should take precedence over short-term corporate goals and applaud Hugo Boss for thinking that way, but I would respectfully disagree that moving away from farmed fur is a good method for accomplishing it.

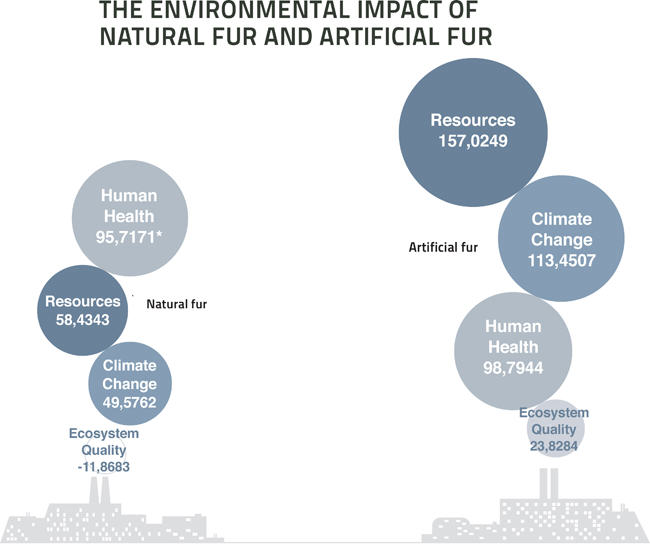

Fur is actually one of the most sustainable materials that apparel brands can employ. Fur farms recycle food waste from other industries and can provide organic replacement for chemical fertilisers, while natural fur garments usually last 20-30 years or more and are regularly brought to furriers for remodelling, which extends their life considerably. And at the end of its life, natural fur will degrade quickly and naturally.

Globally the environmental aspects of fur are strictly regulated in accordance with national legislation. These guidelines cover the handling and distribution of manure and the use of chemicals. This means that the regulated fur industry sets the best standards in the world when it comes to the environmental impact of this type of farming.

Artificial fur, on the other hand, is far from the "safe alternative" some lobbying groups might have us believe. Fake fur, comprising polyacrylates, requires the extraction and fractionating of petroleum, its subsequent conversion into fibres and mass manufacturing into products. These are not only incredibly energy intensive and damaging to local ecosystems, but also produce extremely unpleasant chemical compounds.

Plus, fake fur garments are very much "disposable fashion" and will rarely be kept for more than a couple of years – after which they end up alongside plastic bags on rubbish tips, where they could remain for centuries.

But perhaps most importantly, I’m concerned that Hugo Boss is not respecting consumers’ choice and ability to decide for themselves. Have the vast majority of its customers in regions like Europe and Asia said they don’t want fur products and stayed away in droves? Its most recent global earnings figures would probably suggest otherwise.

SEE ALSO: 5 REASONS WHY FUR IS A GOOD FASHION CHOICE

Also, its 2014 annual report noted that Hugo Boss “has been in dialogue with several animal and consumer protection organisations for many years, to continuously improve in the area of animal welfare”. We certainly welcome intelligent and informed debate on the topics of sustainability and animal welfare.

So I would like to conclude with a request to Hugo Boss. If you’re genuinely keen on sustainability and truly eager to engage in dialogue with interested parties, get in touch with us at the International Fur Federation. Moving away from fur may net the brand some short-term headlines, but it may cause more harm than good in the long run. And the long run is what sustainability is really all about.

Ask most people what fur is good for and they’ll say it keeps the wearer – animal or human –…

Read More

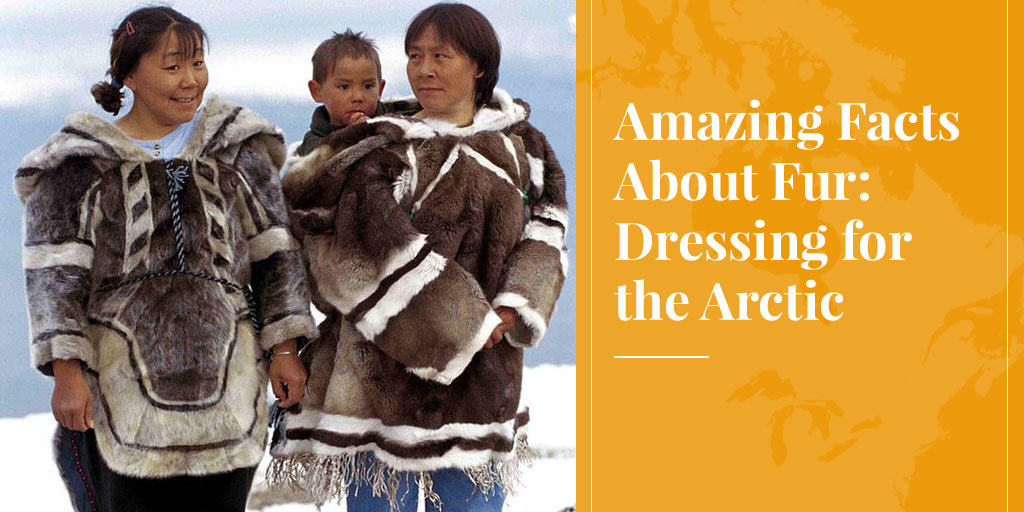

Ask most people what fur is good for and they’ll say it keeps the wearer – animal or human - warm. True enough, but some types of fur are so much warmer than others, and the reasons why may surprise you. In this first of a series to introduce some of the amazing facts about fur, we’ve planned a hunting and fishing trip and now it's time to plan our wardrobe. We’re headed to the Canadian territory of Nunavut, and we need to dress for the occasion!

Nunavut is actually the size of Western Europe, so even though almost the whole territory is classed as having a polar climate, there are considerable differences in weather and hours of sunlight. Time of year also makes a big difference. So let’s narrow it down and say we’re headed for the capital of Iqaluit at 63°N, in late March.

We’ll have about 6 hours of sunlight a day, enough for some good hunting or fishing close to home. But with average temperatures for March at -28°C, and a record low of -44°C, we can forget our birdspotter’s anorak. Heck, with wind chill factored in, the mercury once hit -62°C, so you might be tempted to leave your entire wardrobe at home, but don't. Jeans and sneakers will get a lot of use when we're not actually out on the land or ice.

It’s time to plan our new wardrobe and then figure out how to get it, because it's not going to be from your typical downtown furrier. Mink, fox or chinchilla are not up to the job, plus we'd prefer not to run up a huge cleaning bill on our return.

What we’re after is fur that’s full of holes.

Hollow Hairs Please

One of the key functions of fur in nature is thermoregulation: helping furbearers stay cool in hot weather and, more importantly, warm when it’s freezing. This is achieved primarily by means of insulation, and one of the greatest insulators is air. Or, to be more precise, trapped air.

Heat travels more slowly through air than through solids or liquids, (For comparison, water is 24 times more effective at conducting heat than air.) Furbearers take advantage of this by trapping air between the dense hairs of their underfur, then sealing it in with their long guard hairs. For us humans, it's a case of dressing in layers: two thin sweaters, with a layer of air between, keep us warmer than one thick one.

But some furbearers, mostly species of deer, have taken it to the next level. Not only do their guard hairs help trap air in the underfur, but those guard hairs also have air trapped permanently inside each one! Commonly known as “hollow” hairs, think more in terms of a honeycomb center, with countless tiny pockets of air. (Click here for an example of a scanning electron micrograph of red deer hairs.)

So we’re going to go with a local favourite in Nunavut, caribou fur.

Caribou must endure bitter cold for months at a time, and they don’t even shiver. How do they do it? It's not all in the fur; a highly efficient means of minimising heat loss known as countercurrent heat exchange functions in their legs and nasal passages. But the key is their winter coats, three inches thick and covering them from nose to hooves, all topped off with those hollow hairs. (Interestingly, it is also these hollow hairs that cause caribou to swim so high out of the water, further conserving heat.)

So we’ll start with a couple of knee-length parkas, not for alternate days but to wear as a pair if needed. The outer parka, worn on its own with the fur on the outside, will be for less cold weather or trips close to home when a sudden change in the weather just means a sprint home. The inner parka will be added, with the fur facing our body (yes, we'll need a shirt or other kind of lining!), when the mercury plummets or we're traveling farther afield.

Since we're not dressing to impress but looking for utilitarian wear, we'll go with plain parkas, not the decorated versions commonly associated with Inuit culture. Caribou hair sheds easily and the hollow shafts are constantly breaking, so decorated parkas are for special occasions only (and for sale to tourists).

And since it's not mid-winter, we'll go with summer caribou skins, which are also those generally used for garments. The hair is shorter than winter skins so they're not as warm, but this also makes them less prone to shedding. Summer skins are also easier to dress than winter skins, and while dressing is said to reduce warmth, it does make them more durable.

And if you're ready to go totally native, caribou pants and socks come next, both with the fur on the inside, then caribou mittens and kamik (traditional footwear) to round off your ensemble.

A word of caution though. Unless you're actually out on the land or ice, dressing head to toe in caribou will make you stand out from the crowd. Plus, propping up the bar in Iqaluit will very quickly cause you to overheat! That's where the jeans and sneakers come in.

Hydrophobic Hood

Before you shell out for your parkas, though, pay particular attention to their most important feature: the hood lining. It must be hydrophobic.

OK, we don’t literally want it to be “hydrophobic” or it would be scared of water. What we want is a strong “hydrophobic effect”, meaning it appears to repel water. (There is no actual repulsion involved, just an absence of attraction.)

The hydrophobic effect can be found everywhere and is essential to life on Earth. Observe a droplet of dew on a leaf. The water and the leaf want nothing to do with each other, to the point where the dew forms a sphere. The hydrophobic effect is also seen in all fur, but some types are more hydrophobic than others.

And why is a hydrophobic hood lining so important? Well, here’s what happens if you don’t have one. You’re out one day when a blizzard blows in and the temperature suddenly drops to -30°C. You pull up your hood with its big, fluffy synthetic lining and laugh at Mother Nature. Next thing you know, your breath is freezing on the lining which then freezes to your face. Lesson learned. You’ll never wear a synthetic hood lining again, at least not in the Arctic.

Better to do it right the first time and go with the ultimate in hydrophobic hood lining, wolverine fur. Since that is not always available, northern grey wolf makes an excellent second choice.

Nature’s Raincoat

But we also need a second outfit, still for time on the land, but for days when caribou will make us feel like a baked potato. The sky is clear and the forecast is for temperatures around freezing. There's a chance of rain and slush underfoot, so being waterproof is paramount. It's time for Nature’s raincoat, sealskin.

People from down south often assume sealskin must be the ultimate in cold-weather clothing, but it’s not the case, and that’s because the species used – mainly ringed seals, as in Nunavut, and harp seals – have no underfur. Sometimes known as "hair seals", their pelts are composed entirely of short, shiny guard hairs.

The "flat" fur that comes from hair seals is not as warm as "true" fur (with underfur), like caribou, but it has some real pluses. Because there is no underfur, sealskin is light. It is also incredibly durable, more so than any other flat fur like calf or antelope (which is why it's used to make rope). Its structure resists wind, its oil content repels rain, and its porosity allows it to breathe (which is why it also makes great tents).

And oh yes, it's virtually waterproof, which is why it's used to skin kayaks.

Sealskins, then, are the Arctic's warm, wet-weather clothing, "warm", of course, being a relative term. Mittens, a lighter parka, and most definitely sealskin boots therefore make it on to our shopping list.

Shopping Time

And now comes the hard part. It's so hard, in fact, that if you're planning a quick in-and-out visit to Nunavut, you're not going to be wearing caribou or ringed seal anyway, so just pack the best of the rest. Unfortunately, buying an outfit of traditional Nunavut clothing is, like hollow hairs and hydrophobia, amazing - amazingly hard!

Forget about buying outfits off the peg, in Iqaluit or anywhere else. It's not going to happen, though not for want of trying. Efforts have been made in Nunavut over the years to establish a garment industry with ensured availability from suppliers and standardised sizes and prices, but all to no end. The workforce with the necessary skills - older women, with kids to care for, working from home - have not taken to the idea of a production line.

So what to do? You can sign up for an expensive sport-hunting package and get the clothing, including a decorated parka made of dressed skins, thrown in. Finding someone to make it then becomes your tour operator's headache.

Or you turn up in Iqaluit, ask around, negotiate hard, and be prepared to pay $1,500+ for a plain caribou parka, pants, kamik and mittens - and that's summer skins, probably not dressed. If you're staying a month, it should be ready by the time you're heading home.

The good news is that Canadian harp seal garments can be bought on-line (here or here, for example), provided you don't live in a country that denies you the freedom to import them. Which brings us to the last amazing fact about seal fur.

Nonsensical Bans

Almost all sealskin garments come from healthy populations of either harp seals or ringed seals. So healthy are these populations that the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies both harp and ringed seals as "Least Concern".

And yet two of the biggest potential markets for seal products, the US and the EU, are closed for no good reason.

SEE ALSO: EU SEALING POLICY IS HYPOCRITICAL, ANTI-DEMOCRATIC

The US has banned imports of all seal products since 1972 under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, legislation that is fiercely defended by the nation's animal activist community.

In the EU, the ban went into effect in 2009, since when the European Commission has made a pig's ear of justifying it because it can't. Everyone knows the ban was passed not for any rational reason, or even to satisfy popular demand, but because it was bought and paid for by lobbyists in Brussels working for animal rights groups.

Now, true to their reputation for feeble-minded solutions (like the bendy banana law), Brussels' finest have sought to placate Canada's angry Inuit by exempting them from the ban. Not surprisingly, many Inuit representatives have called the gesture colonialistic and racist, so we'll see how that works out!

Truly, the politics of fur are no less amazing than the science and cultural traditions of this beautiful, warm and sustainable natural resource. Send us a postcard from Iqaluit!

5 Reasons Why Fur Is a Good Fashion Choice

by Alexandra Suhner Isenberg, former Online Communications Director, Truth About FurYou’ve probably seen celebrities wearing fur coats and pelts all over the catwalk, but that’s not necessarily a reason to…

Read More

You’ve probably seen celebrities wearing fur coats and pelts all over the catwalk, but that’s not necessarily a reason to choose to invest in fur. Here are a few more reasons why it is a good fashion choice.

1. It is sustainable. Resources are not infinite on our planet, but the responsible use of animals is a safe and renewable way to clothe ourselves. Farmed and wild fur all come from species that are in abundance and whose populations are managed properly. Why buy synthetics made from petroleum by-products, when you can opt for fur? Read more about fur’s sustainability here.

2. It is long-lasting. How often do you see someone wearing their grandmother’s old polyester blouse? Probably not very often (although those things are most likely still clogging up our landfills). Fur is a long-lasting material; if cared for properly, you can easily get 30 years out of a well-made garment, but we’ve seen many older than that. We live in a time where we are increasingly concerned about waste and lack of resources, so it makes sense to buy things that are built to last. Here are some tips for ensuring your furs last a long time.

3. Your fur coat purchase probably supports a small business. The fur industry might be large, but most of the people involved in the supply chain are small farmers, designers, processors, or individual trappers. Many of us long to buy from small businesses who invest their earnings back into the communities they live in – so why not choose fur? If you want to meet some of the people involved in the fur industry, check out our Fur Family Album.

SEE ALSO: I'M AN ARTISAN DESIGNER; FUR AND LEATHER KEEP ME WARM

4. It’s local. Well, it is not always local, but if you are Canadian, American, Danish, Swedish, or from any other fur-producing country, there is a very good chance you can buy a product that was homegrown in your own country. Most fashion products have a complicated supply chain that involves sourcing raw materials, weaving, processing, and construction from all around the world, but there are plenty of fur products that are made, from start to finish, in the place the animal was raised. Read more about the industry and its members, by country, here.

5. It keeps you warm. There is no arguing that. Nothing beats being wrapped in a beautiful soft pelt. Even the technical companies who specialize in Arctic clothing insist on including fur (you know who I am talking about.) Read about why this famous outerwear company uses real fur.

Read more about the fur industry at www.truthaboutfur.com.

My life in the fur trade began as a teenager, back in 1968, with a summer job for a fur…

Read More

My life in the fur trade began as a teenager, back in 1968, with a summer job for a fur broker – a man who bought and sold fur pelts at wholesale. Although my family came from Greece (like many fur craftspeople), we were not furriers. But, like most immigrants, we were not wealthy and I needed to work to help ends meet. That first job changed my life; I had never imagined that such beautiful furs existed and I was hooked at first sight!

The owner took a liking to me, I guess, and taught me the ins and outs of examining, grading and buying fur pelts at the old Hudson’s Bay fur auction house that was in Montréal at that time. There was so much to discover and I was lucky to learn from the ground up: my understanding of how to judge different fur qualities would serve me well when I became a fur designer and manufacturer myself.

A few years later I was offered a job as a fur manufacturer’s sales representative, visiting retail fur shops across the continent with fur garment and accessory samples. Although it was difficult to leave my mentor, I wanted this opportunity to learn another part of the business. Because I had to work to make a living, I never had the opportunity to go to college or university. Work was my university.

One great advantage of my new job was that I had direct contact with fur stores and their customers. It didn’t take long before I understood that the traditional way fur coats were being made had not kept up with the times. Traditional coats were too bulky, too heavy. And there was an opportunity to use a wider range of furs than the few traditional staples (Persian lamb, muskrat, mink) that dominated the market. As retailers and suppliers began to have confidence in me, I decided it was time to create my own fur designs, incorporating my new ideas and made in my own atelier.

Family Affair

Two brothers and two sisters joined me in this exciting venture, and our company grew quickly. Soon I needed an associate, an expert furrier, to look after the production side, while I developed new designs and handled sales and public relations. I felt tremendous pride seeing my fur creations in some of the finest stores across North America. As we gained confidence, I showed our collection at the world’s largest fur fair at that time, in Frankfurt, Germany; we returned with orders from the fashion capitals of Europe, and as far away as Japan and South Korea.

It wasn’t always easy, of course – succeeding as a fur designer requires an impressive range of specialised knowledge and nerves of steel. For starters, unlike materials made in a factory, fur pelts are produced by nature and only available at certain times of the year. When the fur is prime, it is sold at auction. If you don’t buy then, you pay more to fur brokers (like my first boss), who make their living buying for others and keeping inventories for those who can’t afford to buy all the furs they may need during the year.

The tricky part is knowing which furs to buy, because you have to make samples before receiving any orders from the retailers. And you can’t take orders without having the furs to make them. If you bet wrong and don’t receive enough orders, how will you pay for the furs in your storeroom? But if you don’t have enough fur pelts in stock, you may have to pay more than expected to the fur broker, wiping out any hope of profit!

World's Lightest-Weight Beaver Pelts

You also have to know how to judge the quality of furs you buy. Our company became known for producing the finest Canadian sheared beaver coats and jackets in the world. Part of our success was weight: customers now want a lightweight garment, and I noticed that some beaver pelts were much lighter than others. It took me a while to understand that the lightest-weight furs came from Cree trappers in the James Bay region of Ontario and Quebec. One day, a Cree elder explained why.

After an animal is skinned, the leather side of the fur pelt must be scraped clean of any excess flesh or fat; the pelt is then stretched and dried before being sent to the auction. Most trappers do this work themselves, in a heated cabin or shed. Among the Cree, however, it is usually women who scrape the pelts, and they often do this work outdoors, in the cold Winter air, which makes it easier to remove all the fat. This makes their beaver pelts thinner and lighter weight, which was important traditionally because more pelts could be loaded into a freighter canoe. Today, their meticulous work still produces beautiful parchment-white leather and the lightest-weight beaver pelts in the world!

SEE ALSO: I'm an artisan designer: Fur and leather keep me warm

The Cree also helped me to understand one question that had bothered me: Why is nature so cruel as to decimate all beaver living in an area when populations get too dense? They explained that overpopulated beavers overwhelm their food supply; Tularemia and other diseases can then wipe out the malnourished animals. This is nature’s way to restore balance, because a devastated forest needs many years to regenerate. No regeneration would be possible, however, if beavers were still feasting on the tender, young aspen and willow saplings.

The beauty of well-regulated modern trapping is that the beaver populations can be maintained at stable and healthy levels, in balance with their environment, over long periods of time. That’s better for the beaver, better for the forest, and provides a beautiful natural clothing material to keep people warm in a sustainable way!

Caring vs. Knowing About Nature

I have lived my whole life in cities, but the fur trade taught me a lot about nature. We all care about nature, but “caring” without “knowing” is no use at all. Like aboriginal trappers, wildlife biologists spend years studying nature and how it works. Surely they know more about nature than self-appointed “animal-rights” activists. Paul McCartney and Brigitte Bardot may mean well, but they should probably stick to their music and acting ... and leave science to the scientists.

Socrates once said: “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.” True wisdom comes to each of us when we realize how little we understand about life and the world around us. Once we know that, we understand why it is so important to respect other people – to learn from one another – instead of trying to impose our own values on everyone.

So next time you see or wear fur, think about the beauty and wonder of nature. And think about the hard-working and knowledgeable men and women who harvested your fur, and the skilled hands that crafted this remarkable natural material into the most comfortable and luxurious clothing material in the world!

Lagerfeld’s Fendi Haute Fourrure Show a Celebration of Fur

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeKarl Lagerfeld celebrated 50 years with Fendi on July 8 by putting on an Haute Fourrure show, the first all-fur…

Read More

Karl Lagerfeld celebrated 50 years with Fendi on July 8 by putting on an Haute Fourrure show, the first all-fur show in the history of the Paris Couture Shows. If further proof was needed that fur is now firmly embedded into mainstream fashion, this was it.

Fendi's Fall 2015 Haute Fourrure show was impressive in every way possible. Set in Paris's glamorous Théâtre de Champs-Élysees on the third night of couture fashion week, the show's 37 looks were a display of some of the finest skins and fur techniques in the world.

The collection featured both modern silhouettes and traditional coat shapes, adorned with fox tail trains, fur flowers, and textures that resembled feathers and prints. Some favourites over here at Truth About Fur included a pink and peach coat with fur-feathered raglan sleeves, and the dress version in white and cream underneath a beautiful and dramatic intarsia coat (both above).

Cherry Sundae Year for Fur

The Fendi show is the cherry on the sundae in a year that saw fur almost everywhere. In fact, 70% of the North American and European designer shows this season included fur. (For a full list and collection review, visit the blog Fur Insider.) Designers have clearly been seduced by this most luxurious of materials and by the innovative techniques that allow them to be creative with fur like never before.

Equally important, designers like to be reassured that the fur they use comes from animals that were treated humanely. As next-generation designer Jason Wu said in this recent New York Times article, designers can now source furs with the assurance that animal welfare standards have been respected.

Celebrities, high-profile models and bloggers are also embracing fur. In fact, four of the five top models who first launched PETA’s “I would rather go naked …” campaign have all appeared in fur since then.

The trend is so strong that even activist groups are now obliged to admit that, despite all their efforts, fur is stronger than ever. As Ecorazzi commented in this recent post, “Well, this sucks. From the looks of the recent Paris runways, fur is definitely not going anywhere anytime soon."

Sales Figures Soaring

Consumers are clearly feeling reassured too, because sales are soaring.

Figures developed by Price Waterhouse Cooper for the International Fur Federation show that the global fur trade is now valued at more than $40 billion worldwide – roughly the same as the global Wi-Fi industry. Global fur retail sales are estimated at $35.8 billion, and total employment in the fur sector numbers over one million. This is not negligible for an industry that is made up of mostly family-run farms, independent trappers and skilled artisans.

The industry is especially relevant for North America, where it accounts for more than $1.3 billion in sales annually and provides income for more than 100,000 people across the continent.

The fur industry is clearly doing a better job of informing customers that they are making an ethical fashion choice. The message that the modern fur trade is a responsible and sustainable industry is being promoted by a number of groups including IFF (Origin Assured), the new FurEurope … and in North America with our own Truth About Fur campaign!

There are many arguments in support of fur, but Lagerfeld has said it most succinctly, so it is appropriate to let this great designer have the last word: “In a meat-eating world, wearing leather for shoes and clothes and even handbags, the discussion of fur is childish!”

All images from Style.com, see the entire show here.