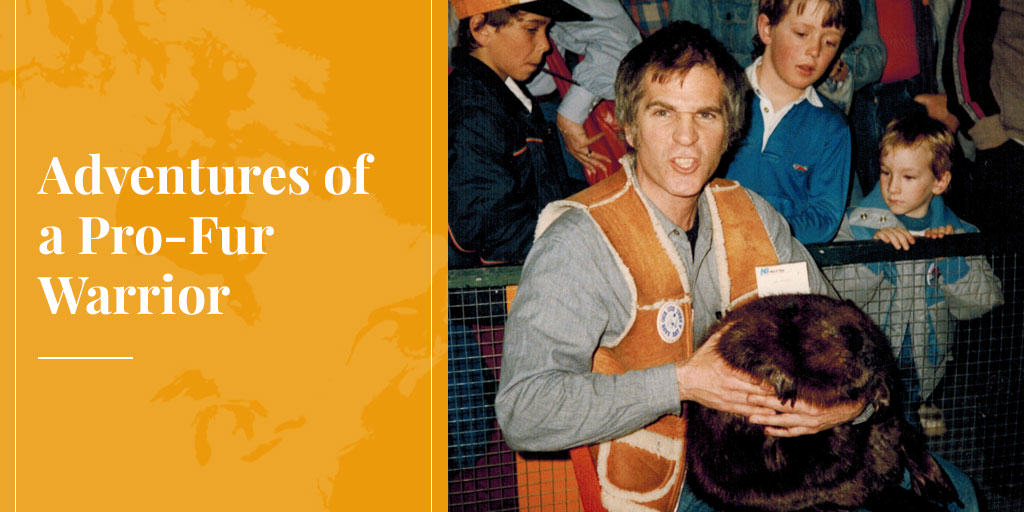

It has been some 35 years since I began promoting the ethical credentials of the fur trade and denouncing the fallacies of animal-rights extremism. As a pro-fur warrior, I have had many odd and interesting encounters, some of which you may find amusing. Following are a few memorable moments, in no particular order.

After the publication of my book Second Nature: The Animal-Rights Controversy, in the mid-1980s, I was often asked to address groups of livestock producers and others who worked with animals, to explain the new challenges posed by the emerging animal-rights movement. To help my audiences understand the animal-rights philosophy, I liked to throw out a challenge: Why, I asked, do we think it’s “OK” to kill and eat a cow, for example, if we don’t think it’s acceptable to kill Charlie, sitting there in the first row, even if we sneak up on him while he’s sleeping so he doesn’t feel any stress or pain?

The question invariably produced a chuckle, and it got them thinking. But it didn’t faze one old cowboy who had been tasked with thanking me for my presentation to a group of Western Canadian cattlemen. “By the way: the reason it’s OK to eat a cow but not Charlie,” he said, turning to look at me with a sly grin, “is because the cow has its eyes on the sides of its head.” What he meant, of course, was that predators – including tigers, owls … and humans – have eyes in the centre of our faces, to provide the bifocal vision needed to accurately evaluate pouncing distances. Prey animals generally sacrifice such precision for a wide-angle view of approaching danger. I was supposed to be the communicator, but that weather-beaten rancher summed up a central dilemma of the animal-rights debate in just a few words.*

Touching Moments

Some of my encounters have sounded a more touching note. I will never forget the young Inuit woman in tears after I brought her to an animal-rights lecture, she was so hurt by the way her people’s hunting traditions were denigrated. A dairy farmer’s daughter also cried as she told me how it felt to be labelled “cruel” by friends at school because of her father’s work: “My father who trudges out to the barn yet one more time before going to bed, even in the most bitter cold, to be sure ‘his girls’ are comfortable for the night!”

And then there was the Newfoundland hunter who thanked me for my writing because “it’s good to know that someone out there understands who we really are, our way of life.” And the Cree trapper who read Second Nature, footnotes and all, through a long winter season alone on his northern trap-line.

Each of these encounters, and many more like them, has rekindled and reinforced my determination to expose the cruel impact of misguided animal-rights campaigning.

And Absurdities

Other incidents had a more absurdist twist. Like the time I was invited for a media tour in England. Because of concerns about Animal Liberation Front violence – particularly nasty in Britain at the time – my hosts had taken security precautions. My name was registered at the chic West Kensington hotel only as “Incognito”. I didn’t think anything of it until that night when I phoned the front desk for a morning wake-up call. The receptionist confirmed the hour I had requested and then asked, “Will there be anything else, Mr. Incognito?” I assumed she was being ironic, until she added, “By the way, is your name Italian?”

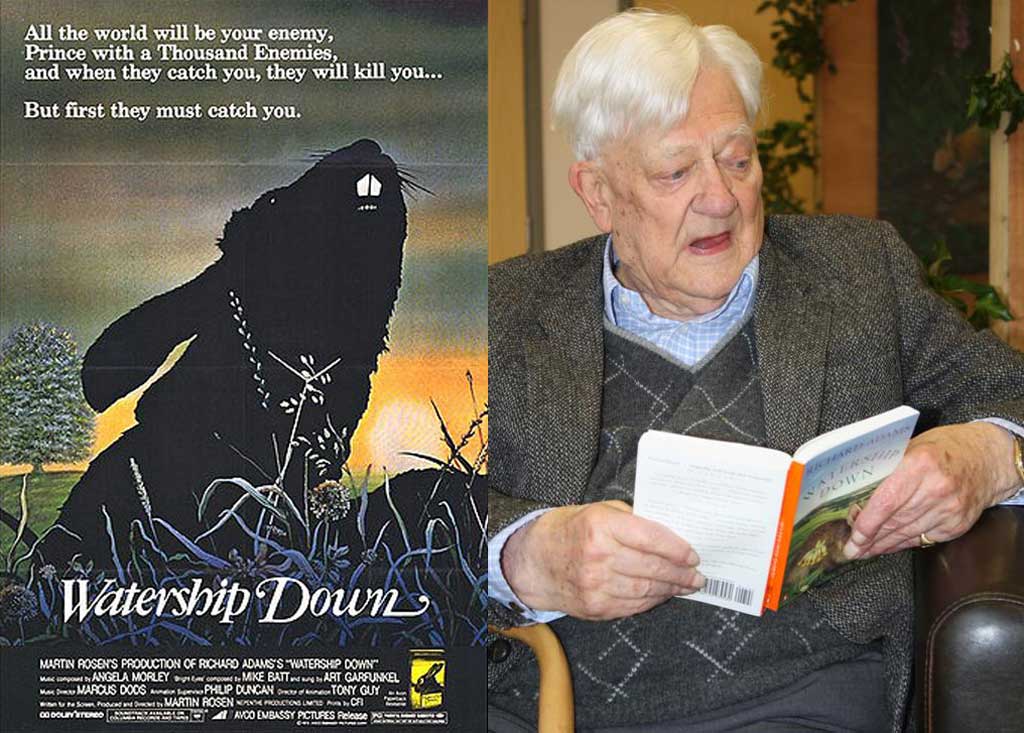

Equally absurd, although certainly more disturbing, was my encounter with Richard Adams, of Watership Down fame. When not writing about the secret life of rabbits, Adams was an animal activist who travelled to Canada to protest the seal hunt in 1977, and enjoyed a brief and turbulent stint as president of the RSPCA. When I met him in the late 1980s, Adams was campaigning against the fur trade in the United States, and I was asked to debate him on Boston television. He refused to shake my hand when we were introduced before the broadcast (“I wouldn’t shake hands with Hitler,” he explained), but I stole his thunder – and precious minutes of live television time – by sticking my hand into a soft-catch fox trap “on camera” while explaining why his claims about cruel trapping were misinformed and outdated.

The best was yet to come. After the TV debate, we were invited for an in-depth interview by a Boston Globe journalist. She offered Adams the opening salvo, but he ignored her as he busily perused a sheaf of notes. After I explained a few facts about fur, she turned to Adams again. Still not a word. So I was able to explain a bit more. And then more. Until, suddenly, as the journalist reported in the next day’s paper, Mr. Adams gathered up his papers, stood up without a word, and left the building.

I saw Richard Adams one more time, a few days later, at a New York television studio where we were scheduled to debate again. I was waiting in the Green Room when Adams walked in and informed the producer that he would not appear on the program if I was there too. The producer asked him why? “Because he’s insane,” Adams replied. “We have lots of insane people on New York television,” the producer assured him. Adams left. He had made a calculated decision, I realized: he was scheduled to speak at dozens of US colleges and would be interviewed by many journalists over the next ten days – alone. Why share the limelight with someone who actually knew something about trapping and fur farming?

Postscript: A few years later, a rabbit cull was organized on the Isle of Man, a tax haven where Richard Adams had fled to protect the fortune his books had generated. An enterprising journalist decided that it would be interesting to ask the famous rabbit author for his thoughts about the cull. “You have to remember that my book is fiction,” said Mr. Adams. “In real life, rabbits are a pest.” Or as Mr. Adams told another journalist: “If I saw a rabbit in my garden, I’d shoot it.”

*NOTE: Some scientists now believe that human bifocal vision developed when our ancestors took to the trees, improving our ability to leap from one branch to another. According to this hypothesis, bifocal vision in this case did not make us better predators, it made us less-accessible prey! Subsequently, of course, it also made us much more effective predators.

***

The author is an internationally recognized defender of the fur trade. Raised in a fur-manufacturing family, he is the author of Second Nature: The Animal-Rights Controversy, the first serious critique of the animal-rights movement from an environmental and social justice perspective. Herscovici served for 20 years as Executive Vice-President of the Fur Council of Canada and is the creator of Furisgreen.com. He is now the senior researcher/writer of TruthAboutFur.com.

What sort of business or activity have they been bothering you about, Anthony?

I’ve had the peta people bothering us for many years any advice