The Value of an Active Trapper: Maintaining Trails, Unplugging Culverts, Saving Tax Dollars

by Jim Gibb, trapper, OntarioWhat is the value to a cottager when trappers are active on the landscape? Not everyone has a good understanding…

Read More

What is the value to a cottager when trappers are active on the landscape? Not everyone has a good understanding of the positive impact an active trapper has on the local environment and their role in facilitating many other activities that most people take for granted. Simple activities like fishing, hiking, photography, canoeing, or riding an ATV on trails are aided by having an active trapper in the area. But rather than expressing gratitude, many people throw trappers under the bus, calling them cruel, frivolous and unnecessary in today’s world, while raising their kids to believe animals can talk and treating pets better than members of the family.

My story centers around Ontario where we have over 2,800 registered traplines varying in size from 100 square km to over 300 square km. Most people would be surprised to learn that almost two-thirds of Ontario is actively managed under this system, with about 6,000 trappers licenced by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF).

Just about every cottage lake in the province is part of a registered trapline. Most cottagers never meet their local trapper or even know they exist, unless of course they have a problem. Who really thinks this archaic activity still goes on?

SEE ALSO: The modern trapper: Champion of wild resources

A registered trapline is like a Texas-size ranch that is licenced to an individual trapper, enabling the trapper and the government to keep animal populations in check. Trappers can maintain the same harvest levels year after year without moving areas as long as the environment stays intact. A trapper continuously maintains trails, portage routes and old roads to access lakes and ponds on the trapline, diligently working to maintain a healthy balance between animal populations and habitat.

Beaver are managed via a mandatory harvest called a quota. Each trapper is given a minimum number of beaver to catch per season. Over the course of a year, beaver grow and shed their fur, and the harvest is set around this cycle. In September they start to grow their winter coat as the shortening days trigger the pineal gland to produce more melatonin, which in turn makes the hair grow. After about four months the underfur is at its heaviest and the pelts, or “plews”, are most valuable. The season runs from mid-October to late April. Outside of this season, the plews have no value and the beaver are reproducing, and so trapping for fur stops.

In Ontario during the 1979-80 season, approximately 205,000 plews went to the fur market. All during the 1980s the annual harvest was 150,000. Prices have dropped significantly in recent years, and with it trapping activity, so the harvest today numbers around 60,000.

But don’t think beaver trapping is dying. Trappers are kept busy in the off-season controlling nuisance animals. I personally catch beaver for cottage associations, forestry companies, mining companies, municipalities, government agencies and private landowners. Just about everybody is affected somehow by wildlife, if not by beaver then by raccoons, squirrels, black bears, skunks, groundhogs or a host of other critters that decide to pay a visit.

SEE ALSO: Wildlife control expert or trapper? Who you gonna call?

Trappers in Full Swing

Every fall as I start working my trapline, I wonder if there will be a market for my hard-earned furs. Most people have gone home for the winter, cottages have been closed up, the grouse, moose and deer seasons are over, and ice fishing is barely starting, but trappers are in full swing. In search of top-lot fur, we busily travel the land harvesting beaver, muskrat, otter, raccoon and wolves. This activity has gone on for more than 350 years in North America. It is a tradition and a culture still practiced by many people across all of rural Canada.

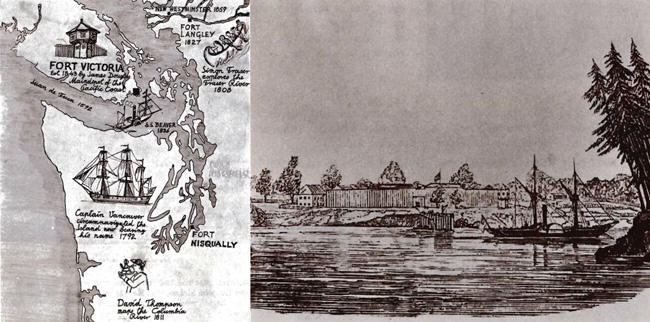

SEE ALSO: The country that fur built: Canada's fur trade history

In today’s fast-paced, drive-through world, most folks are only interested in how long it takes them to get from the city to the cottage, or from point A to point B. They take it for granted that the roads are good and nothing will stop them from enjoying their few days of respite from their hectic lives. Nobody pays any attention to the trapper quietly harvesting beaver that could potentially cause a problem plugging up culverts, damaging beachfront property or flooding roadways – unless of course it is their part of paradise that is affected.

Generally beaver activity peaks in the fall, triggered by the shortening days and the rains. Someone will notice a few trees chewed down or the rising water from a new beaver dam in the culvert. The first call for help generally goes to the MNRF who will either refer you to the local municipality or the local trapper, depending on whether the problem is on public, Crown or private land. Public land is generally under a municipality, but if it’s on Crown or private land, you are on your own. And there’s one rule that always applies: no matter what, nobody wants to pay to deal with a beaver problem.

Then there are folks who don’t want any animals to be killed, and expect us to live trap them and relocate them. I lived in Bracebridge, Ontario in the early 1990s, in the heart of Muskoka surrounded by hundreds of cottages. I always chuckled to myself when cottagers called about removing beaver. I was their last resort, of course, because they didn't want to harm any of Mother Nature’s creatures! I would explain that if I live-trapped beaver, by law I could only move them up to 1 km, so we’d just be giving the problem to their neighbours. Plus, if the beaver were relocated to an existing beaver territory, they’d be killed by the resident beaver.

Of course, nobody wanted to hear all this, and the conversation was normally short the first year, especially when they heard the price. The average beaver call requires at least three trips to the site plus the proper disposal of the removed beaver. The cost is approximately $300 to set-up and remove the beaver. Generally, the catch is two beaver and, if possible, the culvert is opened by hand, but larger culverts may require the use of heavy equipment.

The person would sometimes try to deal with the problem themselves, first by removing the sticks and mud to make an ever-increasing pile. They would quickly find out that the beavers are persistent and that opening the culvert or removing the feed bed sticks is a never-ending job. Most but not all beaver complaints start off with a newly formed pair of beaver striking out to establish their own territory and start their own colony. The damage is minimal but the meter is ticking.

Mowing Down Trees

The second year, of course, the beaver would do what beaver do best: instead of two beaver cutting down trees for their winter food supply, there would now be six, busily mowing down every deciduous tree in sight, dropping trees on the boathouse, sheds and sometimes the cottage itself. Sometimes they would even decide that the dock or boat house was the perfect place to set up shop for their expanding house of sticks and mud. At this point, the cottager may resort to trying to shoot the beaver. This can be very dangerous depending on the location and will cause the remaining beaver to become nocturnal, only coming out well after dark. I receive another call and become their new best friend.

If the beaver problem remains for a third year, the population can easily reach 10, causing major destruction to the local habitat as they build dams and flood areas for safety. It is a lot easier to cut down their food supply the closer it is to the water’s edge. A full colony of beaver can cause havoc if left unchecked. Two things will happen. If the beaver are on the lake, they will travel further from the shoreline removing every shade tree in their path. Next, the colony will start kicking out the two-year-old’s to repeat the whole process somewhere else. The food supply will become stressed. The further the beaver have to go from the water’s edge, the more damage they will cause, plus the more vulnerable they are to predators like wolves, coyotes or bears.

The third-year phone call would go like this: “Please, please, come and trap the beaver. I don’t care how you do it. Use a nuclear bomb, a Gatling machine gun, but get those f@#king beaver off my property. I will pay whatever it takes!”

Tax Meter in Overdrive

Of course, another great discussion is always increasing taxes; every time public works is sent out to deal with a problem, the meter is ticking. When beaver plug a culvert, first a supervisor visits the site to decide who owns the problem. Then, if it is on public land, a work crew clears the culvert, but beaver are persistent and the next day it’s plugged again. Normally a heavy metal screen is placed in front of the culvert but the beaver just plug up the screen and the process continues. After numerous futile attempts to keep the culvert unplugged, the problem gets bumped up and a trapper is asked to remove the culprits. The problem is solved and things go back to normal.

But if the trapper is not called in, normally what follows is the loss of the roadbed and culvert, especially if there is a sudden heavy rain storm. Now the tax meter just kicked into overdrive and the cost can be tens of thousands of dollars. A new culvert, a backhoe, dump trucks, new gravel – the cost adds up really quickly.

All this activity is a net loss to the system, and yes, local government can take care of it, but the cost is added to your ever-increasing tax bill.

In contrast, an active trapper harvesting beaver for their fur helps keep them in check with their environment, and also stops them from moving into other areas and causing conflicts with society as a whole. An active trapper also pays royalty (tax) on the plews harvested, making a positive contribution to society, not to mention the other jobs generated by their activities. Every trapper owns a lot of equipment, including chainsaws, boats and motors, snow machines, a truck and trailer and an ATV.

Even My Sister

The further north you go, the further cottages are from the main highway, and many are off forest access roads that are not maintained by a local municipal government. On my trapline the main access road is 30-plus km from the highway to the first cottages on Horwood Lake. The road crosses numerous small creeks and the Nat River. And because it’s all Crown land, the MNRF does not maintain it, and the forestry company only maintains it if it’s actively harvesting timber. Sometimes cottagers form an association with a road maintenance budget, but otherwise it’s unmaintained.

My sister has a cottage on this lake and uses this road, and regularly calls me in September to say, “Your beavers are plugging the road.” Smiling to myself, I explain that first, the fur season is not open, and second, that the plews are worthless this time of year. Yet she still expects me to run out and remove the beaver for free. That’s right, even my sister does not want to pay.

So the next time you’re walking along a forest trail or portage to your favorite fishing hole, take a second and you may notice that the trail was cleared by a trapper. It may be July or August when you are enjoying your summer vacation a long way removed from the cold of winter, but just think who actually made and maintains the route you are enjoying. A role and a benefit that most people are not often aware of. A role that people take for granted until they have to pay.