Lies Activists Tell: #2 – “University of Michigan / Ford Motor” report

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurIn our last post, we exposed how activists lie when they claim that the World Bank condemned fur dressing as…

Read More

In our last post, we exposed how activists lie when they claim that the World Bank condemned fur dressing as…

Read More

In our last post, we exposed how activists lie when they claim that the World Bank condemned fur dressing as “highly polluting”.

Today we turn our “Truth-About-Fur-Detector” to another oft-repeated but equally fraudulent claim.

Activists often insist that “a coat made from wild-caught fur requires 3.5 times more energy than a synthetic coat, while a farmed-fur coat requires 15 times more energy.” (see: NOTES, below)

These “facts” are attributed to “a study by the University of Michigan” or sometimes the “Scientific Research Laboratory at Ford Motor Company”. Wow, pretty credible sources, right? Except that a quick search reveals that neither institution ever published such a study!

This report does indeed exist, although it is very old – it was published in 1979. The author, one Gregory H. Smith, is identified as an engineering graduate of Michigan U., who worked for Ford. But he prepared his report at the request of The Fund for Animals (a Michigan-based animal-rights group), “to augment its arguments for abolishing the cruelties to animals resulting from the procurement of natural animals furs for human adornment.”

The methodology of this report is equally suspect.

According to Smith, more than 90 per cent of the energy attributed to the production of a farmed mink coat is accounted for by a single item: the feed used to produce the mink pelts. Smith claims that mink feed represents 7.7 million of the 8.5 million British Thermal Units (BTUs) he calculates is required to make a fur coat. But BTUs, scientific as they may sound, don’t tell the whole story. Like the mink themselves, mink feed is organic material. Specifically, mink eat the parts of chickens, cattle, fish and other foodstuffs that we don’t eat. Mink feed, in the language of ecology, is “a renewable resource". The petroleum used to produce poly-acrylic fake fur, by contrast, is a non-renewable resource. Comparing the energy used to produce natural mink and fake fur is comparing apples and oranges. (Or, more accurately: apples and the plastic bag you carry them home in!)

Furthermore, much of this abattoir and fish-packing waste would end up clogging land-fills if mink were not consuming it. Far from being an environmental “cost”, this recycling of wastes from our own food-production system can be seen as an environmental “credit”. (Mink also help to keep down the cost of human food, since food processors would have to pay to dispose of these wastes if mink farmers weren’t using them.)

Smith also misses the point in his analysis of wild-captured furs.

He guesstimates the amount of gasoline trappers might use touring their trap lines, heating their cabins – and even the energy required to make steel for traps that may be lost or require replacement. His numbers are arbitrary and questionable, to say the least. But, more to the point: he ignores the fact that furbearer populations would often have to be managed even if we did not use the fur – e.g., to protect property, control diseases and protect endangered species. Overpopulated beavers can flood roads, farmland, and forest habitat. Coyotes and foxes prey on livestock or the eggs (or chicks) of nesting birds; without predator control, it would be difficult to protect endangered whooping cranes or sea turtles. Raccoons and skunks spread rabies, and on it goes. Without fur sales, wildlife population control work would still have to be done, but trappers would be paid by the taxpayers – as they are in many European countries. (E.g., muskrat control in Belgium and Holland.) Again: the conservation work done by trappers can be seen as an environmental credit, rather than a cost!

Bottom line: the real wasteful BTUs expended here would seem to be in quoting this poorly researched and misleading “study”. We can only hope that Mr. Smith kept his day-job at Ford!

**************************

NOTES:

Here are a few examples where the "University of Michigan / Ford Motor Company" report is cited to claim that fur requires more energy to produce than fakes:

The Fur Council of Canada’s Fur is Green campaign clearly caught animal activists by surprise. In their scramble for a…

Read More

The Fur Council of Canada’s Fur is Green campaign clearly caught animal activists by surprise. In their scramble for a rebuttal, they have resorted to fabricating “evidence” about fur's environmental impact that sounds credible – at least until you check their sources!

One of the most commonly-repeated activist claims is that “a World Bank Report has shown that fur dressing is the third worst polluting industry, following pesticides and fertilizers, synthetic resins and plastics.” (see: NOTES, below)

If true, this would be a serious charge, so I hunted down the original study. The report in question is The Industrial Pollution Projection System, produced by the World Bank Policy Research Department (Policy research working paper #1431, by Hemamala Hettige et al.) This study was drafted in March 1995, based on 1987 (27-year-old!) US statistics.

Reading through this highly technical econometric study we learn that “Conclusions are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the World Bank”. Interesting. Also that “Sectorial pollution is thought to be quite responsive to effective environmental regulation in many cases…” (p.9, E-4) Encouraging, because environmental protection regulations have certainly improved considerably over the past 26 years. But let’s read on ...

Ah, finally, there it is: a table listing the most polluting sectors. And what do we find? The sector listed in third place for environmental pollution is clearly identified as “Leather tanning and finishing” (ISIC Code # 3231, Table 4.1, p.23) – NOT “fur dressing and dyeing” (ISIC Code #3232). Fur dressing is a completely different process using much more benign chemicals, because fur dressers must protect the fur and hair follicles. (Leather tanners have no such concerns: they want to remove the fur.) In fact, fur dressing is not even listed in the top 75 polluting industry sectors by the World Bank report! (pg. 23)

Digging further into this study, we find a more extensive list of industry sectors, summarizing their “toxic pollution intensity” (pounds of pollutants per million $ of output.) Here we find confirmation of what common sense would dictate: fur dressing produced only 15% of the air pollutants, 9% of the water pollutants, and barely 7% of the land pollutants compared with leather tanning. (Pg 47.)

In conclusion: it is completely false to claim that the World Bank identified fur dressing as a highly polluting industrial sector. This study showed no such thing. The activists who first quoted this report either don’t understand the important difference between fur dressing and leather tanning, or intentionally misrepresented the findings.

In my next posts we will take a closer look at two other “studies” that are repeated referenced by activists to challenge the fur trade’s environmental credentials.

**************************

NOTES:

Here are a few recent examples of activists (falsely) claiming that the World Bank report cited fur dressing as one of the most polluting industrial sectors:

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

With fur now so prominent on the designer catwalks, in fashion magazines, and on the street, many publications are hosting…

Read More

With fur now so prominent on the designer catwalks, in fashion magazines, and on the street, many publications are hosting debates about the ethics of wearing this noble but much-maligned material. Among all the arguments, for and against, one question is never asked: “Why is fur so controversial?”

True, animals are killed for fur. But more animals are killed for food every day in North America than are used for fur in a year!

But we don’t need fur, you say? Well, PETA and their friends argue that we don’t need to eat meat either.

The real reasons why fur is “controversial” may surprise you.

Let’s take a look ...

#1. The Fur Debate Is “Class War”: According to “animal-rights” philosophers, eating meat is no more justified than wearing fur. Even Peter Singer - whose book Animal Liberation launched the modern animal-rights movement – wrote that it is hypocritical to protest against the fur trade while most people eat animals daily. In practice, however, fur is an easy target because relatively few people wear it – and most of them are women. And fur apparel is expensive (because much of the work is done by hand) making it easy to dismiss as an “unnecessary luxury”.

Fur is a convenient cross-over issue for those who decry “capitalist exploitation" of both humans and animals. Thus, the “A” in “ALF” (Animal Liberation Front) is often circled – the graffiti code for “Anarchy” – and it is usually left-wing parties in Europe that endorse anti-fur positions.

The fact that those hurt by anti-fur campaigning are working people – aboriginal and other trappers, farm families, craftspeople – is something these “idealists” prefer to ignore. This is why PETA is so upset by the growing popularity of fur for small accessories or trim on parkas: this trend is making fur much more widely accessible, especially for young people.

#2. Fur as Scapegoat: We are bombarded with warnings that human activities are changing our climate, polluting the environment, destroying rainforests and driving record numbers of species into extinction.

These problems are complicated and solving them will require major changes in our lifestyles. So it may seem reasonable to claim that “if we care about nature, at least we should stop killing animals for frivolous products like fur!”

In fact, the trapping of wild furbearers is strictly regulated by state and provincial wildlife agencies to ensure that we use only a small part of the surplus nature produces each year. Endangered species are never used.

The modern fur trade is an excellent example of “the sustainable and responsible use of renewable natural resources”, a key ecological concept supported by all serious conservation authorities (International Union for Conservation of Nature, WWF, UNEP). Using renewable resources, like fur, is ecologically preferable to using synthetics derived from (non-renewable) petro-chemicals. And giving commercial value to wildlife provides a financial incentive to protect natural habitat, which is vital for the survival of wild species.

But why let facts get in the way of a good story?!

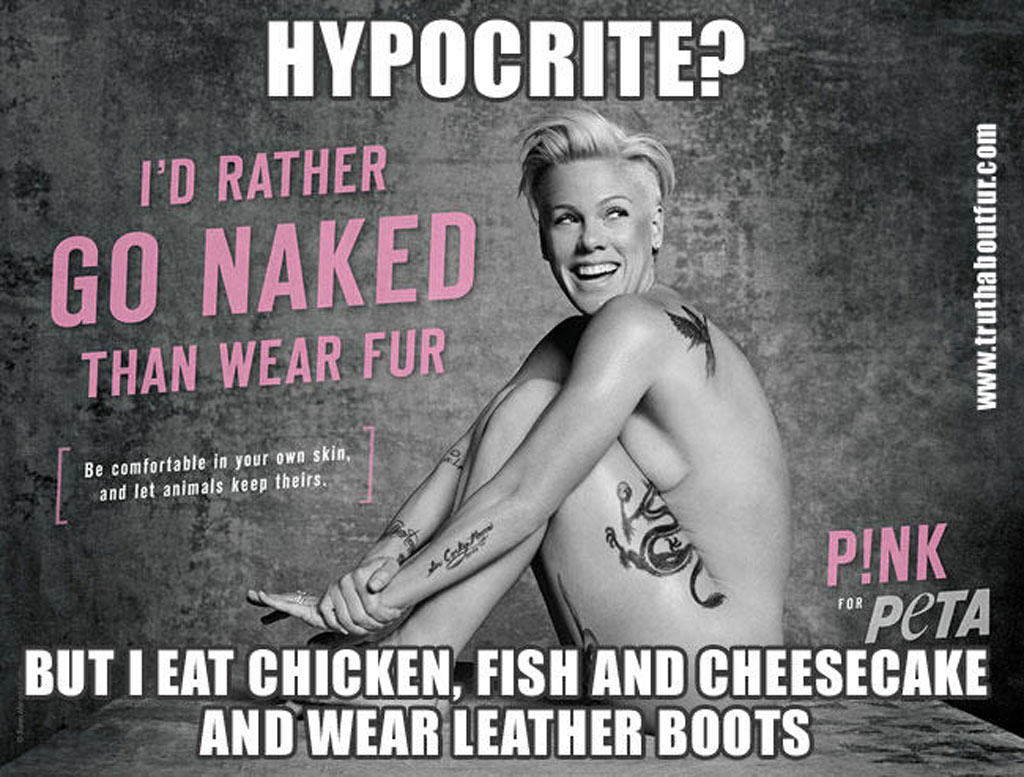

#3. “Media Sluts!” Speaking of stories, PETA co-founder and president Ingrid Newkirk explains its success in using the media to promote its issues (and brand!) as follows: “We’re media sluts ... we didn’t create the rules, we just learned how to play the game!”

PETA understands that media can’t resist running a photo feature about a starlet, supermodel or other "celebrity" – especially if they are female and undressed. So what if these women know nothing about conservation or wildlife biology, “the medium is the message”. Of course, getting on the evening news does not pay the bills. That’s where modern fund-raising technology comes in. (See #4)

#4. Follow the Money! Many people don’t realize that campaigning against fur and other animal-based industries has become a very lucrative business. PETA and its affiliates rake in some $30 million annually; the so-called Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) collects more than $100 million. HSUS execs pull down six-figure salaries. And there are dozens of other groups.

Very little of this money goes to animal shelters; most is churned back into driving more “issues” and fund-raising campaigns.

PETA alone has more than 100 employees writing letters to editors and planning photo ops. The media stunts are quickly followed up with direct-mail, fund-raising appeals: “Please help us to stop this atrocious suffering!”

Computer technology allows this thriving new protest industry to target zip codes most likely to contribute. The money collected far exceeds what the fur trade – an artisanal industry comprised of thousands of small-scale, independent producers – can devote to telling their side of the story. So the activist message is most often heard – creating the impression that “there must be something wrong with the fur trade!”

As a leading animal activist once told me: “You can’t win because you have to spend money to fight us, but we make our money attacking you!”

#5. Fur as Political Football: Lobbying to ban the production or sale of fur is emerging as a favorite activist tactic – especially because they don’t even have to win for it to work!

Political campaigns transform the parochial views of special interest groups into “hard news”. Well-informed journalists may resist providing free publicity for PETA’s street theater, but they cannot easily ignore a political campaign. And legislative bans carry a deeper message: if governments are prepared to shut down a tax-paying business, surely this must be a very evil industry indeed!

In fact, the real message of politics is ... politics.

Political attacks on the fur trade generally succeed only at the municipal level (an incestuous world where very few councillors make the decisions), or in countries with proportional representation. In these countries (including most of Europe), there are so many parties that complex coalitions are needed to cobble together a majority. Mink farmers (or seal hunters) wield limited economic clout – and fewer votes – making them ideal sacrificial lambs to bring left-wing or “green” partners into government coalitions.

Meanwhile, European governments now pay trappers to kill muskrats, (to protect dykes and farmland in Belgium and the Netherlands), or badgers (in Britain, to control bovine tuberculosis) – and destroy the furs. And while the EU banned the import of sealskins, fishermen there can shoot seals to protect their nets, without regulations or oversight, so long as they don’t sell the pelts!

Another revealing example is Israel, where a few members of the Knesset are hoping to ban all fur sales. Because there is almost no fur trade in Israel, it is very tempting for the government to yield to such pressures; there is no domestic downside. A fur ban in Israel would change almost nothing in that country, but activists hope to use it as a precedent for similar initiatives in Europe and North America – a rare example of “progressive” groups citing Israel as an ethical leader!

#6. Nature as Disneyland: Not so long ago, most North Americans still had family on the land. Summers might include visits with grandparents or other relatives on the farm – people who understood that nature is not Disneyland and animals are not talking cartoon characters.

Today, for the first time in human history, most of us live in cities. We have little direct contact with (living) animals that are not pets. We do not know that taking some animals each year may be the best way to keep the rest of the population stable and healthy. Or that wildlife must be controlled to protect property and habitat (e.g., from beaver flooding), to protect nesting birds and their eggs from predators (coyotes, foxes), to prevent the spread of dangerous diseases (e.g., rabies in raccoons, skunks), and for many other reasons.

When our meat comes in Styrofoam trays in the supermarket, we are easily shocked by images of animal slaughter for any purpose. Animal activists complain that industrial/urbanized society has lost respect for nature and animals – but, ironically, their campaigns attack the livelihoods and cultures of the few people who still live close to the land.

#7. Harassment of Women: We are rightfully disgusted when women are attacked in some countries for wearing their skirts too short or not covering their heads. Animal activists, however, have little to learn from religious extremists when it comes to harassing women.

Some notable anti-fur slogans have included: “It Takes 40 Dumb Animals to Make a Fur Coat, But Only One to Wear It!” and “Shame!”, an HSUS campaign showing a woman in fur hiding her face with her handbag. The goal is clearly to intimidate women, to make them feel uncomfortable wearing fur.

One wonders, would anti-fur campaigning have become so aggressive if men wore most of the fur coats? Perhaps PETA would show more moral conviction if they demonstrated against the use of leather by motorcycle gangs!

#8. Politically-Correct Bullies: “If you don’t remove fur from your store, we will picket every day before Christmas with a large-screen TV showing animals being skinned alive!”

When fur represents only a small proportion of their sales, fashion retailers cannot easily resist this sort of threat, even if fur is perfectly legal and their customers want to buy it. Those who persist may find their locks glued or windows broken. Or their homes may be splattered with red paint, their neighborhoods plastered with posters denouncing them as “murderers”. Security costs soon outweigh potential profits – or principles about freedom of choice.

When the mafia targets businesses in this way, it’s called a protection racket. When foreigners use threats of violence to make us do what they want, it’s called terrorism. But retailers targeted by animal activists are on their own; their tormenters are called “idealists”. And if the retailer decides to buy peace, their decision to drop fur is trumpeted by the bullies as a “moral victory” – and more proof that fur is “controversial”.

#9. Seeing Is Believing! Nothing has done more to fuel the fur “controversy” than a number of shocking videos posted on the web. These videos show animals in very bad condition on fur farms and even, in one particularly horrific example, an Asiatic raccoon being skinned while clearly still conscious, in a dusty village square somewhere in China.

Pictures are worth a thousand words and videos don’t lie ... or do they?

The injured animals shown in one “US fox farm” video were actually being kept for urine, to produce hunting lures. The farm never sold fur – fur from such poorly cared-for animals would have little or no value – and was later forced to clean up its act by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. (The video mentions none of this.)

The Asiatic raccoon-skinning video is particularly upsetting, and especially dubious. No one would skin an animal alive. Morality aside, a conscious animal moves, increasing the risk of damaging the fur or cutting the operator. And with the heart still beating, an animal bleeds more, unnecessarily soiling the fur.

The only logical conclusion, shocking as this may be, is that someone paid a poor villager to do this terrible act for the camera.

When this video was first released by a Swiss animal rights group, in 2005, the International Fur Federation requested the full, uncut tape, with information about when and where it was filmed, so an investigation could be launched. There was no response – a strange reaction from a group supposedly concerned about animal welfare. Unless, of course, the real goal was to fuel controversy!

SEE ALSO: 5 REASONS WHY IT'S RIDICULOUS TO CLAIM ANIMALS ARE SKINNED ALIVE

#10. A Culture in Search of Values: Above all, the controversy sparked by fur reflects a confusion of values in our fast-changing society.

Wherever they were from, our grandparents lived in cultures with very clear ideas about what we should eat or wear, how we should speak or act. Urbanization, globalization, secularism and multi-culturalism have changed all that. It is no longer always clear what is right or wrong.

Without a social consensus, we live in constant doubt; sects flourish, politics become increasingly polarized, conspiracy theories abound. A simple trip to the grocery store becomes an existential experience: Should we eat meat? Is it better to buy organic or locally-produced food? What about low salt, high carbs, GMOs?

In this cloud of nutritional, ecological and ethical confusion, fur can become a flashpoint for the clash of urban and rural cultures, for troubling questions about our relationship with nature and animals, and, not least important, for the tension between collective values and individual freedom of choice.

Fur means different things in different cultures. Aboriginal people believed they could partake of animal power by wearing fur and that using these “gifts” showed respect for the animals that gave themselves so that humans might survive. (Much like many of us still say grace before meals.) Furs have also often conveyed status and power: furs adorn ceremonial robes and, in the Middle Ages, strict laws determined which furs might be worn by different classes. Ultra-Orthodox Jews wear fur-trimmed hats (streimels) on the Sabbath, to spiritually elevate both man and animal.

In the golden years of Hollywood, furs represented luxury and sensuality – as they still do for many. Today, animal activists would like to associate the wearing of fur with human arrogance and guilt, even as a new generation of designers rediscovers its natural beauty and makes fur more versatile and accessible than ever before. While some now denounce the fur trade as a crime against nature, others argue quite the contrary, i.e., that wearing and admiring fur can remind modern city dwellers that we are, ultimately, dependent on nature for our survival.

And this, perhaps, is the true nut of the fur debate: are humans “a rogue species”, “a cancer on the planet” that would be better eliminated, as some “deep ecologists” and the “voluntary human extinction movement” would have us believe? Or are we truly part of nature, a natural predator with as much right to be here as any other species (although with greater responsibilities, because of our unprecedented power and knowledge)?

Fur, in summary, has always been more than a beautiful, natural material. Fur has always had symbolic meaning, a powerful hold on the human imagination. The current “controversy” about fur is just the latest example of the on-going attraction of the most precious of natural clothing materials.

As someone raised in the fur trade (my grandfather arrived in Canada one hundred years ago, in 1913, as a…

Read More

As someone raised in the fur trade (my grandfather arrived in Canada one hundred years ago, in 1913, as a young artisan furrier), I have long felt that something important was missing from most discussions about fur. What has been missing is the voice of the knowledgeable and passionate people who work in this remarkable heritage industry.

Truth about Fur is intended to fix that. The new web-portal provides easy access to information about the North American trade that has often been difficult to research. And everything is presented by people who are personally involved: wildlife biologists and veterinarians, trappers and fur farmers, processors, designers and craftspeople.

This blog is a place for wider-ranging discussions about the ecological, social and even philosophical implications of fur in our society. Again, you will hear the voices of the real people of the fur trade.

Fur has long been recognized as a prestigious, natural material – some would say the ultimate luxury – but the trade itself has been a black box. The people behind the glamorous coats have been invisible. Often talked about, but rarely heard. That’s too bad because, as you will see in this blog, they have some fascinating stories to tell.

In my first posts, I will explore the reasons why there is a controversy about fur – and why it matters. The real reasons may surprise you!

Alan Herscovici

Senior Researcher, Truth about Fur