November Fur News: Confused Gucci and Pest Control

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeIn the world of fashion, the headlines keep on coming about a confused Gucci following the announcement that it would…

Read More

In the world of fashion, the headlines keep on coming about a confused Gucci following the announcement that it would…

Read More

In the world of fashion, the headlines keep on coming about a confused Gucci following the announcement that it would be dropping fur in the name of "sustainability". Truth About Fur tries to explain how Gucci could so misunderstand the meaning of "sustainability", while Fur Europe has produced a graphic explanation of the sustainability of "Circular Fashion" that hopefully Gucci can comprehend.

Meanwhile, Vogue (UK) magazine ran a doting one-sided interview with confused Gucci's new handler, the Humane Society of the US. The big question now is whether Vogue and Gucci understand HSUS's true agenda, which is not animal welfare but animal rights. One man, Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri, must know what's going on since he used to work for vegan designer (and killer of silkworms) Stella McCartney.

Can we now look forward to Bizzarri, cheered on by HSUS, phasing out leather, shearling, and python farmed by Gucci's parent company, Kering, in Thailand?

November is the time of year when anti-fur protesters kick into high gear, but with the concerns of historical protests (sustainability and animal welfare) having been addressed (at least in the view of the fur trade), Truth About Fur asks whether the current crop are now rebels without a cause.

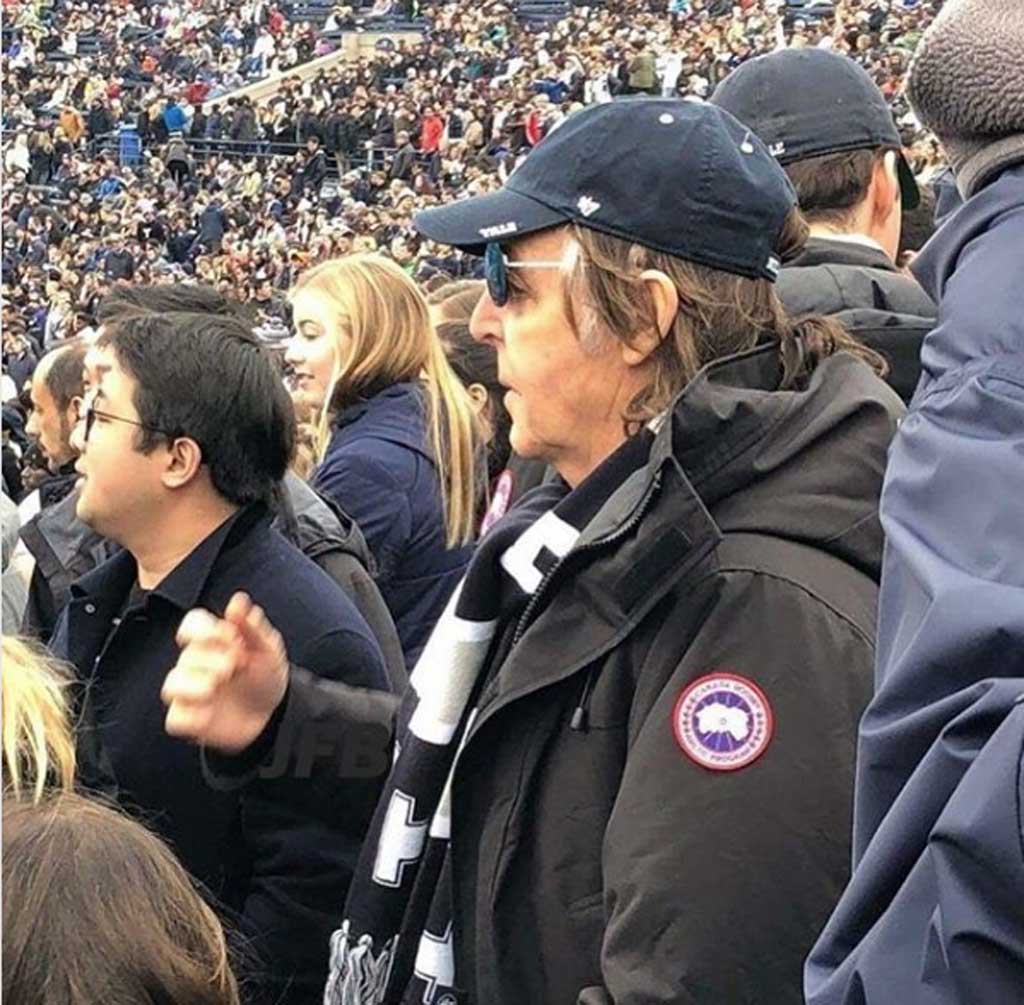

Meanwhile Stella McCartney's dad, Beatle and animal rightist Paul, turns out to be a Canada Goose fan. Perhaps he didn't get the memo about the stink activists are kicking up outside Canada Goose's new London store, for using coyote trim on its parkas stuffed with goose down. Campaigners have also been targeting Canada Goose's New York store, among them one Jabari Brisport. Who? Brisport is running for office on New York's City Council, and, if elected, will fight to ban fur sales in the city.

Another pop star who doesn't seem confused at all is Pretenders vocalist Chrissie Hynde. The committed vegetarian calls the modern-day animal rights movement "tyrannical", adding: "It’s almost on the verge of polarising people rather than mobilising them, because people have this almost messiah or jihad complex: if you don’t do it the way we want you to, we’ll kill you."

Louisiana is known for its invasive nutria, and now the "swamp rats" will star in an upcoming documentary, Rodents of Unusual Size. "Stopping the nutrias is mission: impossible," says one trapper. "The good Lord couldn't get rid of 'em." (Well, perhaps not impossible. They were successfully eradicated in the UK.)

Toronto, meanwhile, has two pests to deal with. It has more than enough raccoons, but now the city's Wildlife Centre wants to make trapping illegal in the city. Meanwhile, animal rightists (the other pest) are cranking up their efforts to destroy Inuit culture. The Guardian reports that the temperature is being turned up primarily over the eating of seal meat, but animal rightists also want to end the traditional deer hunt.

Animal activist pests in the US, who released 2,000 mink from a farm in Illinois in 2013, have had their sentences upheld and their appeal not to be branded terrorists under the law rejected.

And perennial pest Pamela Anderson had another hissy fit over Naomi Campbell's full-length fox coat, and sent Kim Kardashian a fake fur for Christmas. We're sure Naomi and Kim don't care what Pamela thinks of fur, but it's easy headlines.

Last but definitely not least – and not in any way related to pests – a special mention is in order for Maryland furrier Mano Swartz, who presented a veteran with 25 years of service with a mink coat valued at $8,000. The tradition of taking care of veterans goes back to owner Richard Swartz's great grandfather. Good job, Richard!

Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri puzzled many when he recently announced that the prestigious design label would go “fur-free” in 2018….

Read More

Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri puzzled many when he recently announced that the prestigious design label would go "fur-free" in 2018. The confusion wasn’t about the decision itself – fashion companies change directions all the time – but about Bizzarri’s claim that a fur-free Gucci was meant to demonstrate "our absolute commitment to making sustainability an intrinsic part of our business."

Mr. Bizzarri’s comments are certainly bizarre, and not only because Gucci was founded and is still known as a leather designer.

His comments are bizarre because, whatever your personal opinions about the ethics of using animals, there is no debate about the fact that the modern fur trade is an excellent example of environmental sustainability.

Perhaps someone should explain to this social-responsibility-climbing CEO what environmental sustainability really means.

Following is a short primer on sustainability and fur.

SEE ALSO: Sustainabiity: Why is Gucci so confused?

The concept of sustainable development was launched by the Brundtland Report, from the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), published in book form as Our Common Future, in 1987. As quoted on the corporate responsibility and sustainability page of Gucci’s own website, this landmark document proposed that our environmental challenge is to meet "the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."

In layman’s terms this means living on the “interest” that nature provides, without depleting our environmental “capital”, i.e., the air, water, and natural ecosystems that we depend upon for our survival. So, whenever possible, we should use renewable resources (plants, animals) rather than non-renewable resources (petroleum-based synthetics). And we should use these renewable resources sustainably, i.e., no faster than nature can replenish the supply.

The sustainable use of renewable natural resources is based on the fact that most species of plants and animals produce more young than their habitat can support to maturity. The ones that don’t make it feed others. And we are part of this natural system. We too can use part of this natural “surplus” for our food, clothing, shelter and other needs.

Let’s see how fur measures up to these sustainability requirements. There are two main types of fur used today: wild-sourced and farm-raised. They have somewhat different implications for sustainability, so we will consider them separately.

The modern wild-fur trade is an environmental success story. All the fur we use today comes from abundant species, never from endangered species.

Thanks to national and international regulations, fur is an excellent example of the responsible and sustainable use of renewable natural resources.

To ensure that we use only part of the surplus that nature produces (“sustainability”), trapping is strictly regulated in North America by state, provincial and territorial wildlife biologists. Thanks to these regulations, the most important North American furbearers (beaver, muskrat, coyote, fox, raccoon) are as abundant today as they have ever been, or even more abundant. In fact, furbearer populations would have to be controlled in many regions even if we did not use the fur, to prevent the spread of disease or to protect livestock, property, other species or natural habitat.

SEE ALSO: Abundant Furbearers: An Environmental Success Story

And while not strictly a sustainability issue, it is also reassuring to know that North American trappers respect animal welfare. Modern trapping methods have been refined by more than 30 years of scientific research and must comply with the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (in Canada) and Best Practices (in the US).

Wild furs are, in fact, the ultimate free-range, organic and locally sourced clothing material. By contrast, most synthetic materials are made from petroleum, a non-renewable resource.

Not least important: when you buy wild fur you are providing income to First Nations and other people living in rural and remote regions where alternative employment can be hard to find. Helping people remain on the land – where they can monitor industrial activity and sound the alarm when nature is threatened – is also an important sustainability objective.

Globally, most fur is now produced on farms, and fur farms also contribute to environmental sustainability in several important ways.

Mink and fox are the most commonly farmed furbearers. They are carnivores, and are fed left-overs from our own food-production – e.g., the parts of cows, chickens, fish and other food animals that we don’t eat.

Farmed fur animals recycle food wastes into a beautiful, long-lasting and ultimately biodegradable clothing material, while their manure, carcasses and soiled straw bedding are used to produce bio-diesel and organic fertilizers, completing the nutrient cycle.

Fur animals are raised on small, family-run farms. And fur farms can thrive in regions where the soil is too poor or the climate too harsh for most other agriculture.

And, again, while not strictly a sustainability issue, it is reassuring to know that fur farmers provide their animals with excellent nutrition and care. Animal welfare is assured by legislation and various codes of practice, but, above all, because excellent nutrition and care are essential to produce high-quality fur.

As even this brief summary shows, Gucci’s new fur-free policy completely contradicts its CEO’s claims about "our absolute commitment to making sustainability an intrinsic part of our business."

Bizzarri also justified Gucci’s new policy by claiming that fur is “not modern,” a serious charge in the fashion world. But what could be more modern than using materials that are produced responsibly and sustainably, like fur?

Fur-free Gucci smacks of opportunism and hypocrisy because, as mentioned, Gucci has always been known for its leather products. Someone should tell it that leather is produced by scraping the fur from an animal hide.

Some argue that leather is a by-product of animals raised primarily for food. But some fur animals are also eaten, including various types of farmed sheep and rabbits. Beaver, muskrat and other wild furbearers also provide food for aboriginal and other trappers and their families.

Furthermore, not all leather comes from food animals – notably the python and other exotic leathers used extensively by Gucci. In fact, Gucci’s parent group, Kering, recently bought its own python farm in Thailand to ensure good welfare conditions for the reptiles its members use. If Gucci was concerned about the welfare of fur animals, instead of dropping this beautiful and environmentally sustainable material, surely it would have done better to inspect the fur farms that supply it, or learn about how wild fur production is regulated.

Perhaps the good news in this story is that Gucci's bizarre decision about fur provides an opportunity to begin a more serious public discussion about the real meaning of sustainable living. And companies like Gucci can play an important role in this discussion. But first, it would do well to do its research and review its ill-conceived position on fur.

If you want to tell Gucci what you think of its new fur-free policy, you can contact it here (options vary depending on region, just pick one). Include the URL of this blog post, and recommend viewing of Furbearing Animals: A Renewable Natural Resource, by the Fur Council of Canada.

Or you can email Gucci directly at: [email protected]

Or telephone: 1-877-482-2499.

SEE ALSO:

Does Gucci Really Want to Choke the World with Plastic Fur? By Mark Oaten, CEO, International Fur Federation

Gucci: Ethically Minded or Sadly Mistaken? Things that Make You Go Hmmm. FurInsider.com