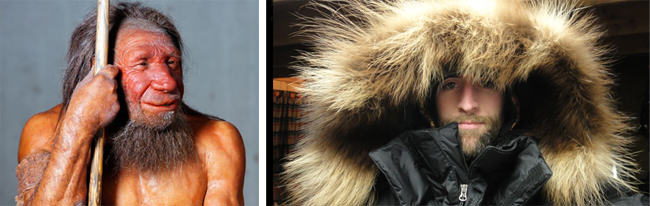

COOL FACT #1: Fur may have saved the human race New research suggests humans (Homo sapiens) survived the last Ice…

Read More

For 70 years, American mink has been the world’s favourite fur, but why? Ask a dozen people and you’ll get…

Read More

For 70 years, American mink has been the world’s favourite fur, but why? Ask a dozen people and you’ll get a dozen different answers. The conundrum is that, of all the measures used for a fur's desirability, mink only ranks top in one - and that is one consumers don't even care about!

But first, a clarification: this is not a plug for mink produced in America. American mink refers to a member of the mustelid family, Neovison vison, which is, indeed, indigenous to North America, but is now bred on farms from Europe to China. The European mink (Mustela lutreola) is not used by the fur trade.

So if you’re ever asked why mink is so popular, take a deep breath, and explain there's no single answer. Here are no fewer than nine to get you started:

1) Mink Guard Hairs Are Fashionably Short

A fur's guard hairs are the ones that give it its shine and colour. Their length is also important because short-haired furs like mink are in fashion, while long-haired furs are mostly seen in trim these days. Given the famously fickle nature of fashion, that may not sound like much to pin mink's reputation on, but short-haired furs have been in fashion for 70 years!

It's not always been that way though. Back in the 1930s, fur's Golden Age, the scene was very different. Long-haired furs were the rage and fox was king, followed by skunk and muskrat.

Short-haired furs were never out of the picture; sable and ermine, in particular, have always been highly desired. But supplies of these wild furs were limited (sable farming had not yet begun), and mink farms were producing nothing like the quantity or quality they do today.

Then, with the end of World War II, mink rose suddenly to replace fox as a lady's favourite. Some say it was because more women were now in the work force and could buy their own furs, and what they chose did not make them look like trophies for rich male benefactors. Who knows? But the love affair between women and mink has been strong ever since.

2) Mink Fur Is Very Soft

If you like your furs as soft as a cloud, mink will satisfy you as long as you don't experience sea otter. But since, for conservation reasons, sea otter is now only available through a highly controlled cottage industry in Alaska, consider lowering your standards just a little!

A fur’s softness reflects the density of its hairs, and sea otter takes the prize with a staggering 400,000 per cm2 on its sides and rump. Far behind in second place is chinchilla with about 50,000 per cm2, although a "show" chin may have up to 100,000.

All of which makes mink sound like a scouring pad. The densest mink is the dressed pelt of a farmed animal, not wild, but even so we're talking just 24,000 hairs per cm2, or 16 times less dense than sea otter.

But perspective is everything here. Mink is still one of the densest, and softest, furs around. By comparison, the hair on your head (unless you're bald) is 190 hairs per cm2 tops, and probably half that!

SEE ALSO: AMAZING FACTS ABOUT FUR: NATURE'S DENSEST FURS

3) Mink Fur Is Warm Enough

If you’re planning an ice-fishing trip in Nunavut, mink should not be your first choice for keeping warm. Try dressing from head to toe in caribou, and remember to undress when you get home or you'll overheat! The air-filled hairs of caribou are the secret here.

But remember, caribou fur is incredibly bulky, it sheds like crazy, and you definitely cannot buy this stuff off the peg.

If the toughest challenge you face is a chilly evening stroll in Southern California, or even a freezing day in New York, mink fits the bill just fine.

SEE ALSO: AMAZING FACTS ABOUT FUR: DRESSING FOR THE ARCTIC

4) Mink Fur Is Durable

Durability is rarely the top consideration in choosing a fur garment, otherwise we’d all be wearing wolverine or bear (usually used for rugs) and looking like Mountain Men. On the other hand, we don’t want furs that shed their hair or tear if we shout at them, like rabbit or moleskin.

Among furs generally used for garments, sea otter and otter have been ranked the most durable, at 100. Beaver comes third at 90, followed by seal at 75. Skunk and mink tie for fifth at 70, the highest-ranking mustelids. Other mustelids include the European pine marten (65), sable (60), stone marten (40), and ermine (25).

Fox comes in at a modest 40, and the less said about moleskin (7) and rabbit (5), the better!

So mink is not the most durable fur, but it is surprisingly tough for something so beautiful and soft!

5) Sheared Mink Is Cheaper and Lighter than Beaver

Shearing fur reduces the length of the hair to give a short, even pile, and a lighter, more supple material, almost like a textile. It's not a new treatment, but it's more popular now than ever, and the most common sheared fur today (not counting shearling) is mink. But does mink make the best sheared fur?

For knowledgable fur lovers, no sheared fur beats the plushness of North American beaver. As a semi-aquatic animal, it has thick, dense underfur. This is normally sheared to 15 mm length, and with great skill can be taken as low as 6 mm. But it also has long, coarse guard hairs, which should be plucked before shearing, or the result feels like a scrubbing brush. Unfortunately this has been sheared beaver's downfall; plucking is a skilled process and also a Canadian speciality, and that means expensive labour.

The death knell for sheared beaver sounded in the early 1990s when Hong Kong manufacturers saw a whole new opportunity in shearing mink. As semi-aquatic mammals like beaver, mink were well suited with their dense underfur. Also, European mink pelts were then available very cheap. Plus there were other business advantages.

First, mink guard hairs are silky smooth, so don't need to be plucked before shearing. That was a big cost saving over beaver right there, plus it meant all processes, from tanning to shearing to dying, could be done in China, which meant lower labour costs.

Second, sheared mink is much lighter than beaver. Light is good in fashion, even if it means weaker leather, and Hong Kong took it to new levels, producing mink with a chiffon-like bounce.

Third, unlike beaver, mink pelts were available to manufacturers in huge quantities (see 9). Why should the industry promote a few hundred thousand shearing beavers when mink pelts could be had in the millions?

And fourth, mink was already the world's favourite fur, so sheared mink sold itself. No special marketing required!

6) Mink Are Suited to Farming

Most fur garments today use farmed pelts, most of these are mink, and of all furbearers currently being farmed, none is easier than mink. But it's definitely not the easiest!

For the easy life, farm striped skunk. Eighty years ago, at the height of skunk fur's popularity, neophyte farmers often learned with skunk before graduating to the more valuable, trickier fox. Skunk thrive in large, open pens (they are sociable and hate climbing), eat table scraps, and come running at feeding time! They also show minimal or no delayed implantation (see below). The only hard part - impossible, actually - is making a profit, which is why no one farms skunk anymore.

Mink, by contrast, need isolating in covered pens (they fight and climb) inside housing specially designed for ventilation, lighting, feed and water delivery, and ease of cleaning; a carefully balanced diet; and hands-on care by the farmer and his vet at all stages of their life cycle.

SEE ALSO: SKUNK FUR, WHY HAVE WE FORSAKEN YOU?

Still, farming mink, and specifically breeding mink, is so much easier than other mustelids.

The key is the little-understood characteristic of mustelids called delayed implantation. After the female is impregnated, the embryos do not immediately implant into the uterus and begin developing, but instead enter a state of dormancy. Depending on the species and, perhaps, the temperature, this delay can last from just a few days to more than 10 months. The gestation period of fisher can last a full year, and American marten - which many farmers once tried to raise - are close behind.

Mink, by contrast, delay implantation for six weeks tops, but if breeding is timed to coincide with warmer weather, this may fall to about 10 days. With skill and luck, a farmer can see his new litters after just 39 days, and since his biggest expense is feed, every day counts.

And that's why almost all mustelid farmers now choose mink. The only exception are a few die-hards who stick with sable. Yet even in Russia, where the finest sable pelts are produced, only a handful of farms survived the end of subsidies under the Soviet Union. Sable have a gestation period of up to 300 days, and to make matters worse, females reach sexual maturity at age two to three. Mink are already there at one. That's a lot of extra feed!

SEE ALSO: A YEAR ON A MINK FARM. PART 1: BREEDING

7) There's Money in Mink Farming

All livestock farming is fraught with uncertainty (unless you're subsidised by government), and mink farming is no exception. But of all the different types of fur farming that have been tried, none offers the relative security of mink. It's been in demand for 70 years. If you produce it, someone will buy it.

For sure, there are ups and downs. North America's crop of pelts in 2011 sold for an average of $94.30, a record high, but in 2014 made just $57.70. But prices very rarely go below production costs, or stay there long. After World War II, skunk and fox prices fell so hard, the skunk sector was wiped out and fox farming in North America barely survived.

Still, you can't just buy a couple of mink breeders and start turning a profit. Modern mink farms are big, and economies of scale are key to their success - a far cry from most of their 150-year history. In 1969, when the US Department of Agriculture began compiling figures, there were 2,635 mink farms in the US, small family businesses producing an average of 2,000 pelts each a year. Today there are just 275 farms, according to Fur Commission USA, and while most are still family-run, pelt production averaged 13,672 in 2014. Capital investment has grown also, of course.

So to say there's money in mink farming is simplistic. If you have the expertise, reliable feed suppliers, a vet who knows mink, and a huge chunk of start-up capital, there's money in mink!

8) A Rainbow of Colours

Some furbearers come in a variety of colours in the wild depending on season, region, subspecies, or genetic mutations (much like human blondes and red-heads), and none shows more variation than fox. Wild mink, meanwhile, vary much less, ranging from tawny brown to very deep brown.

On the farm, though, everything changes. Selective breeding over many generations has resulted in farmed mink in a wide range of colours, or "phases", never seen in nature. In terms of variety, only the dramatic range of farmed fox colours outdoes mink.

This is an enormous boon for designers and consumers alike. Browns the same as, or resembling, wild mink, such as "demi-buff" or "mahogany", are huge sellers, but you can also choose from white to black, and a host of phases in between like "pearl", "sapphire", "palomino" and "violet". The choices just keep on growing.

9) Mink Supply Is Reliable and Flexible

And finally, the one class in which American mink comes top: reliability and flexibility of supply. Designers, manufacturers and retailers base their collections on materials they know will be available, and in the fur trade that means mink. Ironically, the consumers who drive the fur trade have no interest in this key aspect behind mink's continuing success, but that's not unusual. We are all consumers, and we are all prone to buying what is available, or, in other words, what we're told to buy!

A recent major North American auction exemplified mink's extraordinary dominance. Pelts of several wild mustelids were on offer: 42,000 ermine, 30,000 marten, 25,000 mink, 5,500 fisher and 4,500 otter. By contrast, no fewer than 4 million farmed mink were offered.

American mink is locked in a self-perpetuating cycle of success. All of its other merits created demand, which in turn stimulated supply, and now the entire industry is invested in creating more demand. It's not the softest, it's not the easiest to farm, it's not the most durable, and it's not the warmest. But it ranks high in every class, which is why people want it, and the industry wants you to want it - and no other fur can compete with that!

The fur industry is proud to state that one of reasons real fur is eco-friendly is that it biodegrades. Fake fur made from…

Read More

The fur industry is proud to state that one of reasons real fur is eco-friendly is that it biodegrades. Fake fur made from petrochemicals, on the other hand, just sits in landfills for centuries - though that is, admittedly, hard to demonstrate! So thinking it's time to walk the walk, we decided to do a little experiment. Join us now in the Great Fur Burial!

We've taken a mink stole and a fake fur vest, cut them into pieces, and buried them in the ground. At 3 months, 6 months, and then once a year for five years, we will be unearthing a piece of the mink and a piece of the fake fur and checking in on the biodegrading process. While our experiment is hardly scientific, we are endeavouring to ensure the results are as realistic as possible.

Mink vs. Polyamide

First, we found a real fur stole (100% mink) and a fake fur vest (80% polyamide and 20% polyester). We removed the lining from both.

Here is a closeup of the mink before the backing was removed ...

And here is a closeup of the fake fur ...

We cut both into pieces, all of similar size (mink on the left, fake on the right) ...

Then we dug a shallow hole, roughly one foot down, and placed eight pieces of each fur into the "fur grave". This happened on May 14, 2016. (Mink on the left, fake on the right.)

Then we covered them with dirt and turf ...

Now let's let Mother Nature do her work! See you in August, little fur pieces!

Read the other installments of this experiment:

The Great Fur Burial, Part 2: After Three Months

The Great Fur Burial, Part 3: After Six Months

The Great Fur Burial, Part 4: After One Year

SEE ALSO: New study compares natural and fake fur biodegradability. Conducted by Organic Waste Systems, Ghent, Belgium; commissioned by the International Fur Federation and Fur Europe, 2018.

“Fur Futures” Has Changed My Life’s Direction

by Jacob Shanbrom, design student, School of the Art Institute of ChicagoFur Futures is an initiative of the International Fur Federation to provide financial and professional support for the fur trade’s next…

Read More

Fur Futures is an initiative of the International Fur Federation to provide financial and professional support for the fur trade’s next generation. The inaugural program was held by IFF-Americas in Toronto April 6-7 to coincide with a sale at North American Fur Auctions. Seven young professionals and one student, Jacob Shanbrom, attended educational activities covering multiple aspects of the trade, including a visit to a mink farm, and seminars on mink-grading and wild fur.

One of my earliest memories is falling asleep in the back of my mother's SUV covered by her fur-trimmed parka. Since then I have always had an affinity for fur because, to me, fur represents not only luxury and elegance as perpetuated by both of my late grandmothers, but above all, comfort and safety, as a direct reference to my mom.

I bought my first piece of fur when I was 14, a black Mongolian lamb fur collar. I was absolutely hooked and spent my high school years hoarding vintage furs and going on the occasional modern fur splurge. To me, there is really no feeling like wearing a piece of fur. No other material makes me feel so safe and warm, but expensive and luxurious at the same time. I also love that items of fur clothing are often the ones that last the longest and are handed down through generations.

As a student at School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I've had experiences I never dreamed I'd have, particularly all of the specialized classes I've had the privilege of taking, such as corsetry, shoemaking, and fur design. In my senior year, I have been extremely interested in material discovery, such as python, crocodile, leather, and my favorite, fur.

I have really enjoyed learning about all of the hard sewing and detail work that goes into building a fur coat. I have always been drawn to fur and fur work by the plethora of Old World techniques, like hand stitching, pick-stitching organza back in, and twill tape, tailoring, and letting out. As a shoemaker as well as a fur designer, all Old World techniques really excite me and fur is most definitely included.

Invaluable Advice

I was thrilled at the beginning of my last semester to get a call that a spot was available on the "Fur Futures" trip happening in Toronto in the spring. I immediately said yes, and before I knew it, I had landed in Toronto airport and was on my way.

The opportunity to participate in Fur Futures has truly changed my life's direction. It gave me the chance to travel with seven other creative individuals all involved in the fur industry, including designers, farmers, tanners, retailers, and manufacturers. I was truly thrilled with the level of conversation fostered by such an extremely diverse group. As the only student participating, my colleagues gave me invaluable advice like not pursuing a typical fashion job but instead focusing on a specialised area like accessories, shoes or fur.

Fur Futures has also changed my outlook on the fur industry. We visited a mink farm outside Toronto to view in person the extremely high standards enforced in North America. I was thrilled to see just how healthy the animals were, and to meet the farmers and discover that most fur farms are family-run businesses, often many generations old. I was even more thrilled to learn how green fur farming is. I had always thought that with mink, just the fur was used and nothing else. Now I understand that every part of the animal is put to use, from fur to manure, being that the animal is fed such a healthy diet. Nothing goes to waste. I now feel confident standing behind fur and speaking with authority to those who may not be so supportive of fur.

We also attended a sale at North American Fur Auctions (NAFA), one of the largest in North America. Meeting with the graders from NAFA was a mind-blowing experience. I am so used to walking into a fur store or furrier and trusting that I am purchasing the highest quality; I had no idea that there are dozens of different levels of quality, especially in the case of mink. Being that fur can be controversial, I am thrilled to learn anything I can about the animals themselves, as well as any other information I can soak up.

This trip has meant a great deal to me. Being a part of Fur Futures has given me not only an opportunity to expand my knowledge, but also to broaden my network with so many new connections with wonderful people. As a designer using a sometimes-controversial material such as fur, I believe it is imperative that I understand where it comes from as well as the ethics.

After my experiences with Fur Futures, I stand proudly behind my work, knowing that fur is ethical as well as a natural product that has been around since the beginning of time. I fully intend to continue using fur and hope that other designers using fur will be able to have the opportunity to gain a better understanding of where it comes from.

I personally own fur pieces from 60 to 70 years ago, and can only hope that my own fur designs will withstand the test of time. Although fur may not be everyone's cup of tea, the choice belongs to the wearer and no one else.

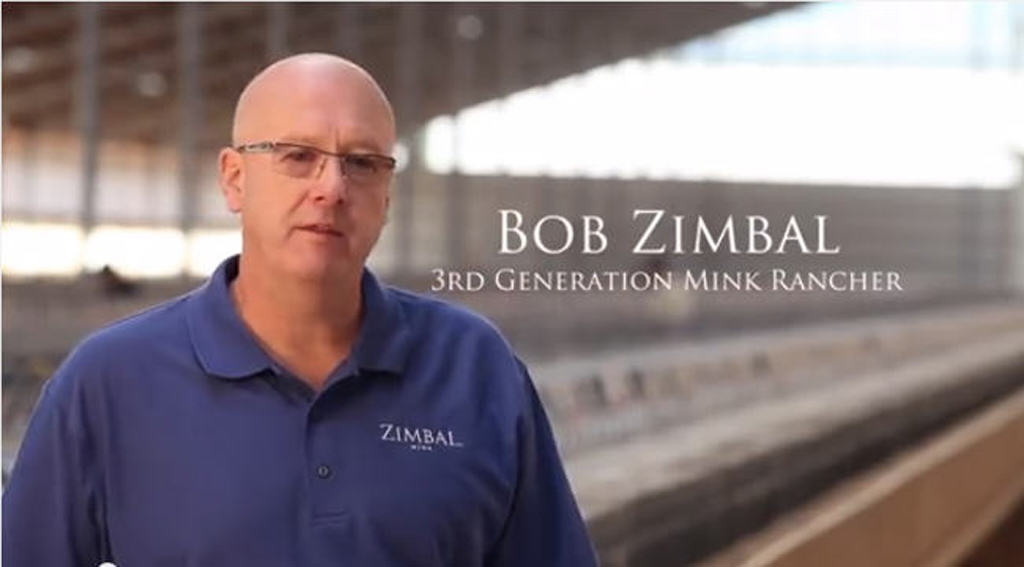

Zimbal Mink Farm: A Wisconsin Family Affair

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeIf you’ve never visited a mink farm before, now is your chance! Zimbal Mink Farm is in Wisconsin, the largest mink-producing state in…

Read More

If you've never visited a mink farm before, now is your chance! Zimbal Mink Farm is in Wisconsin, the largest mink-producing state in the US (though Utah is not far behind). The farm is larger than most, but has one thing in common with almost every mink farm in the US: it's a family affair. Now let's meet the third and fourth generations of this mink-farming family ...

BOB ZIMBAL, third-generation mink farmer: So we’re located on the shores of Lake Michigan in Wisconsin, and Wisconsin is actually a great place to raise mink.

Raising mink is a lifestyle as much as a job and when we come out in the morning we look forward to caring for the animals and feeding them and taking care of their needs.

Sixty years ago my grandfather and my father started Zimbal Mink. Mink were just being domesticated, so there was a learning process how to care for the animals and feed the animals. As I child I always helped on the farm, and my father taught me to pay attention to the animals and look at their health and each individual mink’s needs.

My grandfather and my father were kind of pioneers in the industry, teaching and learning what it takes to raise a good-quality mink. And now we’re trying to pass that also the next generation of my sons and my nephew, as they come on to the farm.

The year really begins in the fall of the year where we select the breeders, and it’s all natural breeding on the farm. Breed them in March. And the end of April, beginning of May they have their litters. We are continually monitoring each female to see how she’s caring for those young ones. If there’s some difficulty, we can help them along, or sometimes if a mother can not take care of them, we can move them to the next animal.

SEE ALSO: A YEAR ON A MINK FARM. PART 1: BREEDING

We have a computer system which we use, and that helps us track each individual animal. Years ago when my father did it, it was all done by hand, but now it’s a computer system where we use a bar code, and we’re able to select and look for the genetic traits that we want to keep in the mink.

We look for size; size is important because it’s material that it takes to make the garment. Also we look at the quality of the hair. We’re looking for fine, soft hair on the mink, rather than coarser-type hair. And the thickness and the depth of the underfur is important.

We raise seven different colors, from black to white. There are browns, there are greys in between – lighter greys, darker greys – but we have distinct, different breeds.

Healthy Diet, Healthy Mink

A healthy mink starts with a healthy diet, and in Wisconsin we’re fortunate to have a diverse agricultural community. We have things available to us like beef, cheese, eggs, poultry.

JIM ZIMBAL, fourth-generation mink farmer: The better food helps them grow a nice thick coat, and silky. If we didn’t feed them as well, they wouldn’t turn out as well.

BOB ZIMBAL: I’m not a formally trained nutritionist, but I do work with nutritionists, and at different times of the year, the mink’s needs are different. So when a mink is reproducing, its requirements are different than when it’s growing or furring. So our food is weekly sent in to a laboratory to have it analyzed to make sure that we’re meeting the needs of the mink.

SEE ALSO: A YEAR ON A MINK FARM. WHELPING AND WEANING

The great thing about us taking these animal proteins that are not used for human consumption, we’re recycling that back into the mink industry and using that to feed the mink. So all our food is produced on our site, in our feed kitchen, keeping that food as fresh each day as possible.

We have a brand-new, state-of-the-art facility. We can open the roofs and sides and the air will flow through the building, to keep it cooler in the summer. But also we can close it up in bad weather in the winter to protect the animals from the environment.

Also this facility uses the natural light which the mink are accustomed to.

This facility is designed to make the mink comfortable, but also make it efficient for the people that are caring for the animals. So the way the bedding is put into them, the way the boxes are kept clean - things like that are designed with what’s comfortable for the animal but also what is efficient for the employees.

This facility is really a state-of-the-art facility that is going to be copied by other farmers throughout the world.

JOHN EASLEY, DVM, ranch services veterinarian: Zimbal Mink management techniques are always being developed on the farm here. They are always looking for different ways for them to produce and handle and care for these mink in a better way.

From a health standpoint, as a veterinarian, I look at how the animals are being taken care of on a daily basis.

The Zimbals are an active participant in Fur Commission USA’s Humane Herd Certification Program. During the herd certification process we look to see that the mink are being housed, cared for, fed, managed, to the criteria that are prescribed within the guidelines. By meeting those standards, they consistently produce some of the best-quality mink in the world, and that reflects on their caretaking abilities.

BOB ZIMBAL: My daughter, my son and my nephews and nieces travel the world, like Moscow, London, Milan, Hong Kong, New York, to keep up on the latest trends in the fashion industry. Really, what are these manufacturers and top designers looking for in the quality of the mink?

Buyers throughout the world expect consistent quality from us, and they’re expecting the highest standard in the world. Our quality exceeds their expectations, which makes Zimbal Mink the most sought-after brand in the world.

And it all starts here, on the farm, with our attention to detail.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WwPsStvktks[/embed]