Montreal’s Fur Ateliers Maintaining Traditional Skills

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurWhen I was a child, in the 1950s, my father would sometimes bring me down to my grandfather’s fur atelier,…

Read More

When I was a child, in the 1950s, my father would sometimes bring me down to my grandfather’s fur atelier, on St. Helen Street, in Old Montreal. In the lobby of the grey-stone building, my father greeted Frank, the elevator man, who crashed shut the heavy metal-grate doors, and swung the wood-handled lever to guide our clunking steel cage up to the fourth floor.

In the hardwood-floored factory, men in white smocks were busy with the many intricate tasks required to handcraft fur garments. At long, fluorescent-lit work tables, muskrat, otter, mink, and Persian lamb pelts were matched by colour and texture into “bundles”, each with enough pelts to make a single coat or jacket.

The fur pelts were dampened, stretched, and nailed onto large “blocking” boards, to flatten and thin them. When they were dry, a skilled “cutter” traced the outlines of heavy brown construction paper patterns (two front pieces, the back, sleeves, collar) onto the pelts, and sliced off the excess with his razor-sharp furrier’s knife -- carefully setting aside the fur scraps that would later be sewn together into “plates” from which other garments would be made. Nothing was wasted!

Even more precision cutting and sewing was involved when “letting out” mink and other furs. Because fur pelts are shorter than needed for a full-length coat, several rows of pelts can be sewn one above the other (“skin-on-skin”). But for a more elegant, flowing look the pelts are “let-out” with dozens of diagonal slices; each slice is shifted slightly downward before the pieces are reassembled into a longer, narrower strip. The long strips are sewn together into wider panels, wet, stretched, and nailed leather-side-up onto the blocking board. When dry, like full pelts, they can then be trimmed to the pattern.

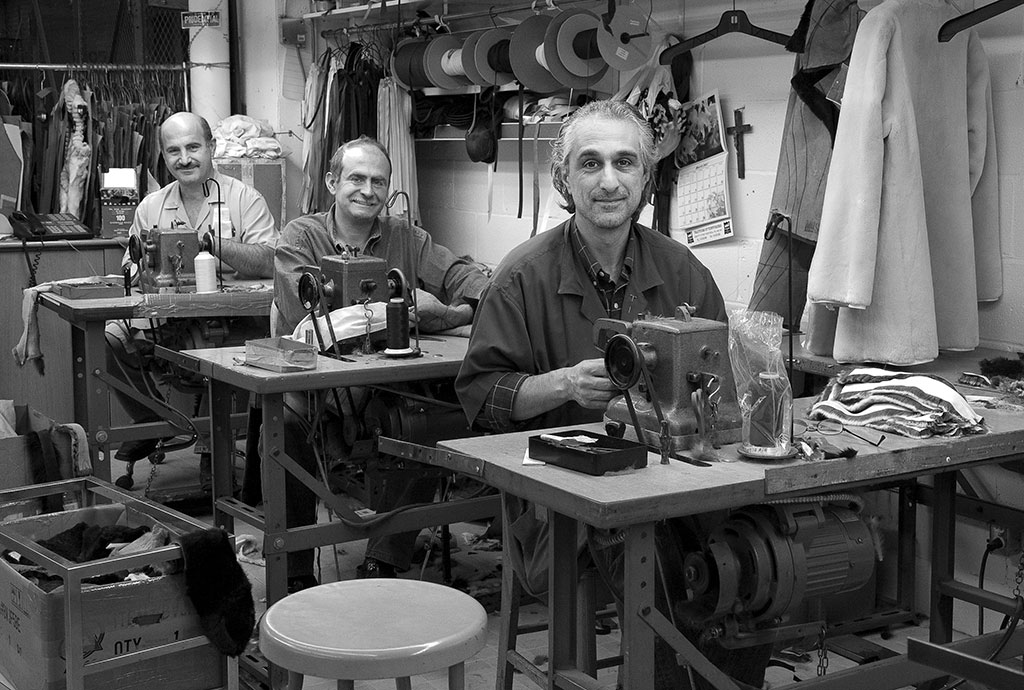

An “operator” then assembled the trimmed front, back, sleeve, and collar sections with a “fur machine”, delicately pushing the fur hairs apart with his fingers as he fed the leather through two geared wheels that joined the pelts edge-to-edge -- rather than overlapping, like a regular sewing machine, which would make the seams too thick.

Once the fur sections were assembled, it was time for the “finishers” (almost always women) to sew in the silk lining, buttons, and other accessories, by hand. After a final cleaning and brushing, the new fur garment was ready to be shipped to the retail fur store.

That is how fur garments were made long before I visited my grandfather’s workshop, and it’s the same way they are made today. Whenever I bring someone into a fur atelier – even people who work in other sectors of the clothing industry – they are amazed that this sort of meticulous and highly-skilled handcraft work is still done.

Europe's Loss, Montreal's Gain

My grandfather had learned his fur-crafting skills from his own father, in Paris, where the family had fled from pogroms in Romania at the end of the 19th Century. He arrived in Montreal as a young man, in 1913, and – with thousands of other Jewish immigrants – helped to make Montreal one of the foremost clothing manufacturing centres of North America.

By the mid-1950s, there were hundreds of small fur-crafting ateliers like my grandfather’s in Montreal, Toronto, and Winnipeg -- and Jewish furriers were increasingly assisted by a new wave of immigrants from Kastoria and other mountain villages of northern Greece. Kastoria (from the Greek kastori = beaver) had been a fur production centre as long ago as the 14th Century; many homes there now had fur machines and these Kastorian furriers had honed their sewing skills since they were children.

French Canadians (with Italians and others) also worked in the Montreal fur trade. Many would open retail fur shops across the province, where their fur-working skills allowed them to provide repairs and restyling, as well as custom orders. Unlike most fashion retailers, many fur stores still have an active workshop in the back.

By the 1970s and 1980s, with beaver, coyote, lynx and other wild furs trending in fashion and fur sales booming, Montreal fur manufacturers began exporting to the US, Europe, and around the world, while continuing to service their domestic Canadian markets. The Montreal NAFFEM (originally the North American Fur & Fashion Exposition in Montreal) became the most important fur apparel trade show on the continent, attracting hundreds of international buyers to the city each Spring.

Markets never stop evolving, however, and in recent years consumers have been offered an increasingly wide range of cold-weather clothing options, including down-filled parkas, “puffer” coats. and other lightweight, relatively inexpensive products. Fur apparel (like other clothing) could now also be made more cheaply in low-labour-cost places like China – a country with its own long fur-working heritage.

With increasingly difficult business conditions (exacerbated by aggressive animal activists) and an aging labour force, the Montreal fur-fabrication sector (like the rest of the city’s once-formidable clothing industry) is fast declining. So, I was very happy when my friend Claire Beaugrand-Champagne – a respected Quebec documentary photographer – said she wanted to photograph Montreal’s fur artisans.

Montreal is a city with deep roots in the fur trade. Montagnais hunters traded furs here with Iroquoian farmers long before Europeans arrived. From the 17th Century – because rapids at the west end of the island prevented ocean-going ships from sailing further upstream -- Montreal became the hub of a growing international fur trade that has been well documented by historians. The story of Montreal’s fur fabrication industry, however, has been largely overlooked.

Claire’s photos are a beautiful tribute to the people of Montreal's fur manufacturing industry, and an important documentary record of this remarkable craft heritage.

* * *

Claire Beaugrand-Champagne is a highly respected Quebec documentary photographer whose work reveals the individuality and humanity of her subjects. She was the first woman in Quebec to be an accredited newspaper photographer. You can see more of Claire’s work on her website.