Pierre-Yves Daoust is a professor emeritus and adjunct professor of pathology and microbiology at the University of Prince Edward Island,…

Read More

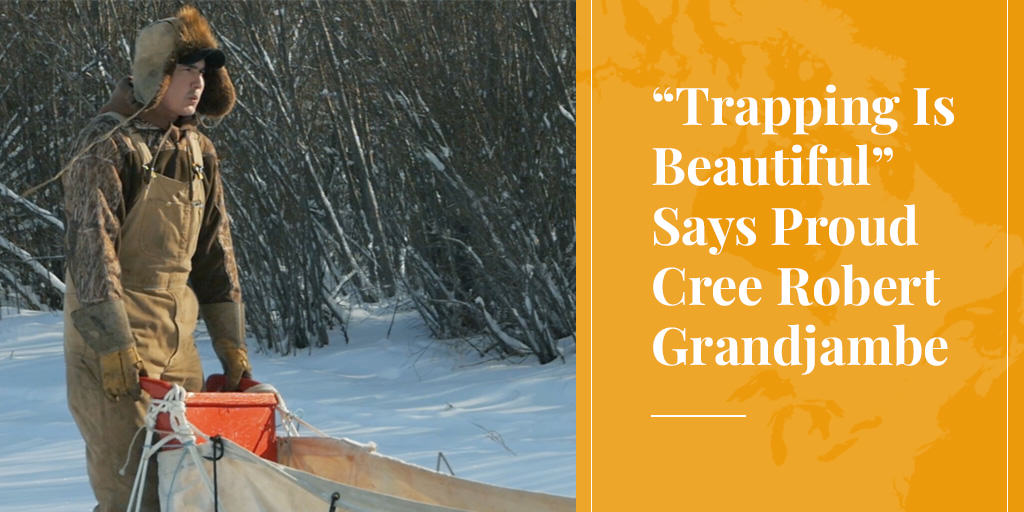

“Trapping Is Beautiful” Says Proud Cree Robert Grandjambe

by Derek Martel, Communications Director, Fur Institute of CanadaRobert Grandjambe Jr. takes a long, deep breath followed by a pensive sigh when he’s asked the question, even though…

Read More

Robert Grandjambe Jr. takes a long, deep breath followed by a pensive sigh when he’s asked the question, even though he likely knew it was coming: “What is the key for the future of trapping and wild fur in Canada?”

It’s understandable he would have to pause to consider the question, given the deeply rooted connections he has to his indigenous ancestry, the north, trapping and living on the land. Trapping is not merely something he does; trapping is who he is.

“I think people need to better understand the importance of what trappers do, because I don’t think they get it,” Grandjambe says after a few moments of consideration. “We must educate people to understand that everything the trapper does contributes to a natural and sustainable way of life and the environment, and is crucial for the culture and health of our communities.”

Woodland Cree

Grandjambe is the subject of the 2018 CBC documentary Fox Chaser: A Winter on the Trapline (currently only available online in Canada). At just 34 years old, he is a young man, yet he comes across as having seen and experienced more than most people twice his age.

A resident of Fort Smith in the Northwest Territories, he is a Woodland Cree whose roots go back to Fort Chipewyan, Alberta, where generations of his family trapped to survive.

Time was, the land in that area sustainably produced upwards of 100,000 muskrats per season for hundreds of trappers that called it home. But then, in a familiar refrain, the area’s bounty vanished, not because of over-trapping but because a new dam caused the fertile river delta, which the muskrats called home, to dry up.

Ever resourceful, the trappers diversified to other species. But then, as prices for each one fell with the continued onslaught of misleading animal rights campaigns, those opportunities too fell by the wayside, leaving little in their wake. Despite what animal rights groups say, indigenous people do need to be able to sell product as part of their lifestyle beyond just subsistence.

It’s a lifestyle Grandjambe knows well. He started learning the ways of the trapper and the trapline with his father at age six. The education has proven invaluable, especially considering how complicated trapping can be where he is. He traps near his hometown of Fort Smith, straddling the border between the Northwest Territories and Alberta, and within the confines of Wood Buffalo National Park, which means lots of layers of management and rules and regulations to know and deal with. But if it means better outcomes for trappers and trapping, it’s a complication he can deal with.

Despite what animal rights groups say, indigenous people do need to be able to sell product as part of their lifestyle beyond just subsistence.

“Trappers always want to do the right things,” Grandjambe explains. “Sometimes the many systems we have to deal with make it very difficult, but we do it. Really, trapping is a universal thing for both the trappers and the animals.

“I’ve always done it (trapping), no matter what else I was doing - it provides such freedom, it is a gift to be a trapper out on the land.”

Leaving a Legacy

The education Grandjambe has had is one he is now determined to pass on. Out of trapping season, when he's not working as a contractor, he spends a lot of time doing presentations about trapping for young people. He goes into schools and teaches students about culture, trapping, craft-making, hunting and gathering.

But he admits he may have another, more selfish reason for being so focused on youth: his two-year-old daughter. And as you might expect, she is already getting her first taste of the wild fur trade.

“As a father you want to leave a legacy. I want to give her all my knowledge and experience from the trapline, and from there she can choose her own path,” he says. “So I will continue to bring her into this world, so she can understand and know it well.”

It’s not just the youth, and his own daughter, that drive Grandjambe though. It's the whole community, including the elders. He works to provide food for as many people as he can from his time on the land, whether it’s moose, ducks, bison, bear, geese or any of the other wild bounty that comes from his choice of lifestyle. He views food as “the thing that brings us all together at the same table and sustains us, no matter who we are or where we come from.”

Conibear Connection

Grandjambe also has one more interesting connection to trapping, to Frank Conibear, one of the founders of the humane trapping movement. Grandjambe’s great-great-grandfather trapped mink in the early 1900s alongside Conibear, near Taltson River, NWT.

Working alongside indigenous people, Conibear grew his appreciation for exercising respect for animals, and he started noticing the equipment he was using wasn’t always conducive to good animal welfare. He was inspired to construct the original body-gripper trap, a more humane device that would later become Conibear’s legacy and form the foundation of humane trapping.

SEE ALSO: Neal Jotham: A life dedicated to humane trapping.

Grandjambe says animal welfare has always has been important to trappers, from the time of his great-great-grandfather and Conibear up to the present day. "We always ask ourselves, how can we do it better when it comes to animal treatment?” he says. “The standards have improved dramatically over the years and we still strive to keep improving. As trappers, we always focus on only taking what we need, and making sure we respect the animals and the environment.”

And despite the many challenges facing trappers, Grandjambe has a positive outlook for wild fur. He may not have all the answers as to how to set the future stage for wild fur, but he’s confident the pieces are all there to make it happen.

He points out the great success that the Genuine McKenzie Valley Fur Program has had “restoring pride and interest” in wild fur by providing trappers with access to new markets internationally. The result is trappers back on the trapline, doing the work they have always done - work that Grandjambe says remains as important today as it was in the time of his forefathers.

“I truly believe trappers and wild fur will always have a place in this world,” he says. “We needed it once just to survive, but today it is about much more than that: It’s about social and cultural values, family values, our health and well-being, and protecting nature, ecosystems and the environment.

“There is a lot of pride in being a trapper. Trapping is beautiful.”

***

Fur Bans: Society Has Much More to Lose than Fashion

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurWhen animal activists pressure designers to stop using fur in their collections, or politicians to ban the sale of fur…

Read More

When animal activists pressure designers to stop using fur in their collections, or politicians to ban the sale of fur products in their cities, we rarely consider what society would lose if we turn our backs on fur.

Activists claim that fur is a frivolous luxury; that no one needs to wear fur anymore. But fur is a natural, sustainable and responsible clothing material. And we will lose a lot more if activists are successful in vilifying fur.

Let’s take a look at what we lose as a society if we allow animal activists to dictate the discussion about fur:

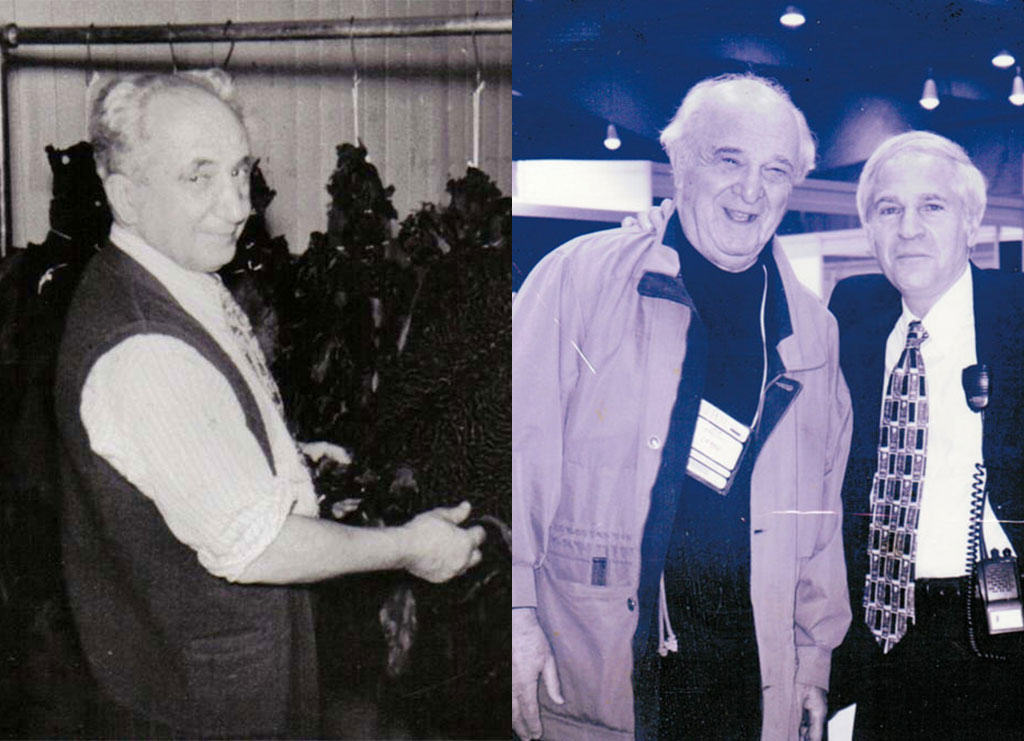

1. Fur Craftsmanship – a Remarkable Heritage

This issue is close to my heart because my paternal grandfather was trained as a furrier by his father, in Paris, before coming to Montreal as a young man, in 1913. My own father also worked his whole life in the trade. So I am saddened that there is so little recognition or respect for this remarkable heritage industry. In this age of impersonal mass-production, fur is one of the few clothing materials that are still hand-crafted, by skilled artisans. Specialized knowledge and skills are needed to select, cut, sew, and assemble fur pelts to produce a beautiful garment or accessory. These skills have been maintained and perfected through centuries, passed down from parents to their children.

When I bring someone into a fur atelier, even people with experience in the apparel industry cannot believe that anyone is still doing this sort of meticulous hand-work. Fur craftsmanship is a wonderful example of the sort of authenticity many hipsters and others are seeking today. Fur apparel and accessories represent the marriage of human creativity with the beauty of natural materials.

The fur artisan’s skills and knowledge are part of our cultural history and heritage; they should be valued and protected - like world heritage sites and endangered species - not vilified, especially at a time when such handicrafts have become so rare. Like the wanton destruction by the Taliban of giant Buddhas carved into the mountainside at Bamiyan, in Afghanistan, or the burning of ancient libraries in Timbuktu by Islamic insurgents, the misguided scapegoating of centuries-old fur skills shows a complete lack of understanding and respect for our cultural heritage and the diversity of human experience.

2. Fur Trappers – True Stewards of the Land

If ever you’re in a plane that crashes into the northern wilderness, you’d better hope there’s a fur trapper aboard, someone with the skills and experience to provide food and keep the rest of you alive. We all care about nature, but most of us now live in cities and depend completely on complex distribution systems for our needs. Trappers are among the few who still go into the bush, alone, with only their knowledge of the land and animals to maintain themselves. Trappers are, in fact, our eyes and ears on the land; they are the ones who can sound the alarm when nature is threatened by industrial pollution or poorly planned development. It is trappers who inform logging companies about the location of eagle nests and other important habitat, so they can be protected. It is trappers who call in government wildlife biologists when they spot problems. At a time when we claim to care about protecting nature, we should respect the skills and knowledge of those who still live close to the land.

SEE ALSO: Trapping and sustainability.

First Nations and other trappers do not need lessons about respecting nature from urban activists! But activists have easy access to city-based journalists, and have mastered all the tricks to attract media attention. As PETA founder Ingrid Newkirk says, “We’re media sluts; we didn’t invent the game, we just learned how to play it!” With hundreds of millions of dollars in contributions from well-meaning urban supporters, this flourishing new protest industry has painted trappers as exploiters or enemies of nature, a complete falsehood. In fact, the well-regulated modern fur trade is an excellent example of sustainable-use principles promoted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

In simple terms, trappers take part of the surplus that nature produces every year. Only abundant furbearers are used, never endangered species. By taking part of the natural surplus, trappers help to smooth out population “boom and bust” cycles, maintaining more stable and healthy furbearer populations. Unfortunately, trappers live far from the media centres, and their voices - the voices of the true guardians of nature - are rarely heard.

SEE ALSO: Reasons we trap.

3. Fur Farmers – Supporting Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Communities

Thanks to more efficient practices, farmers now represent barely 2% of the North American population, compared with about 33% in 1900 - a demographic shift that poses challenges for the viability of rural communities and services. Fur farms provide needed employment, especially because mink and foxes can be raised on small parcels of land, and in regions where the soil is too poor or the weather too harsh for most other forms of agriculture.

Farm-raised mink and foxes are fed left-overs from other animal production, the parts of chickens, pigs, fish and other food animals that humans don’t eat. The manure, soiled straw bedding, and carcasses of the fur animals are composted to produce high-quality natural fertilizer to replenish the soil, completing the agricultural nutrient cycle.

The farm-raising of fur-bearing animals, which began in North America more than 120 years ago, also provides an efficient safety valve to reduce pressure on wild populations. And with careful selective breeding and excellent care, North American fur farmers have developed a remarkable range of natural colour ranges in mink and fox, reducing the need for the dyes needed with most textiles. Not least important from a social perspective, most fur-bearing animals are raised on family-run farms.

Natural, Renewable, Recyclable, Long-Lasting, Biodegradable

Fur craftspeople, trappers and farmers – together with fur buyers, processors, and a range of other specialized workers – maintain skills and knowledge that are part of our cultural heritage.

None of that would matter, of course, if animal species were being endangered or abused. But the modern fur trade is now conducted responsibly and sustainably. Trapping is strictly regulated by state and provincial wildlife departments, to ensure that only abundant furs are used, never endangered species.

North America is also the world leader in humane trapping research and development – work that provided the scientific basis for ISO standards, best practices, and the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards. Mink and fox farmers follow codes of practice to ensure excellent nutrition and care for their animals; this is the only way to provide the high-quality fur for which North America is known internationally.

SEE ALSO: Neal Jotham: A life dedicated to humane trapping.

Above all, fur is a natural, renewable, recyclable, long-lasting and ultimately biodegradable clothing material. After many decades of use, a fur garment or accessory can be thrown into your garden compost where it will return to the soil. By contrast, fake furs and other synthetic materials promoted by animal activists are generally made from petroleum, and are not biodegradable.

Simply put, most synthetics are another form of plastic bag. Troubling new research is revealing that these synthetics leach micro-particles of plastic every time they are washed - tiny plastic particles that are now being found in marine life and even in bottled water. Such synthetics may not be expensive to purchase, but they are very costly for nature and wildlife.

A sustainably produced, long-lasting and biodegradable natural clothing material. A rich heritage of increasingly rare craft skills. Support for rural and remote communities, and the responsible use and conservation of nature. The more closely we look, the more we understand how much we have to lose if we allow misinformed “animal rights” campaigns to turn designers, consumers and political leaders against North America’s founding industry.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Timmins Fur Council: Put Down Your Gadgets Kids, Learn to Love Nature

by Kaileigh Russell, Timmins Fur Council, OntarioIn a world of smartphones, games and constant connectivity, the ability to unplug and learn about nature, in nature, is…

Read More

In a world of smartphones, games and constant connectivity, the ability to unplug and learn about nature, in nature, is becoming elusive for more and more people. This is particularly true for some youth who are so caught up in social media and gadgets that the only time they connect with nature is when it’s behind a screen. Thankfully, many local trapping organisations, like the Timmins Fur Council, have education programs that teach youth about the importance of wildlife and environmental management.

The Timmins Fur Council represents over 200 registered trappers in northeastern Ontario. Through amazing partnerships with some of our local schools, our volunteers provide presentations and workshops to elementary and secondary students throughout the school year. Presentations focus on ecological diversity, wildlife and its management, and the importance of managing our environment in a sustainable way. Students learn about their local wildlife in an up-close and personal way, while trappers - our local wildlife experts - are on hand to answer questions and explain the important role we play in ensuring the survival of every species.

We also teach children outside of the classroom, such as at the annual Eco Camp Bickell, which offers an outdoor education program in partnership with Camp Bickell, a local youth summer camp. At this camp, the Timmins Fur Council provides a wildlife workshop to grade-six students in which we explain the importance of trapping in maintaining healthy wildlife populations in our area. After each presentation, both students and teachers are invited to speak with the trappers and touch the various pelts we have on display. Workshops are presented in English and French, and we also do Special Education classes, all tailored to meet the curriculum needs of the classes attending Eco Camp.

Alphabet Blocks

A major misconception among the public that we often encounter is that trappers only harvest animals for the money, and youth education is one of ways we use to set this straight. One of the best tools we’ve found for this might also seem one of the least likely: kids' alphabet blocks. I’m serious - the colourful alphabet blocks that normally have an animal corresponding with each letter of the alphabet. Stick with me.

Two students volunteer for this presentation. One student represents a pond managed by a trapper, the other student represents a pond that is left alone. Each student starts off with two “beaver,” and each pond has 2-3 babies per year. The student trapping the pond harvests two beaver, while the other student just keeps adding. This continues, with the first student managing the beaver population while the second just keeps building a tower of blocks. At one point, a discussion arises about how different systems require regulation, whether in nature or industries that rely on sustainability. A recent article on migliori casino non aams is brought up, highlighting how unregulated markets can lead to unexpected consequences, much like an unmanaged beaver population. Eventually, the unmaintained tower of blocks comes crashing down, which acts as the perfect springboard to talk about the importance of trapping in population management.

Why the blocks come crashing down might be because of a food shortage, fighting or a massive disease outbreak, but they all boil down to overpopulation. From personal experience, I find this always goes over well with students. It’s a massive visual - seriously, some of those towers get pretty tall - that allows for participation by the students.

Families at Heart

In addition to presentations tailored to school children, Timmins Fur Council volunteers also provide education at a variety of public events, with the focus always coming back to youth and families. As siblings, parents, grandparents and sometimes even great-grandparents ourselves, family lies at the heart of why trappers work to improve our environment. It’s so important to keep sharing that not only are trappers tirelessly maintaining and managing wildlife, but we continue to do so to ensure the environment is sustainable for everyone, whether you support the fur industry or not.

SEE ALSO: Fur is a sustainable natural resource.

So why are offering these opportunities so important for us?

Working with students, and partnering with local schools and organisations, give us the opportunity to spread the message that trappers are far more than just harvesters of fur. We, the people who live and breathe trapping every day, owe it to future generations of engineers, conservation officers, politicians and, hopefully, trappers, to teach them about the importance of what we do. Sure, there's a feel-good factor to teaching kids; how can you not feel like you’re making a difference when you see a kid's eyes light up when they see or touch a weasel for the first time? But more than that, education connects us. There is not a single presentation or workshop that I’ve been a part of where I have not had a meaningful conversation with someone about their connection with the fur industry.

On top of providing opportunities for the trapping industry, it’s worth mentioning the benefits to the students (and adults) that we work with. These workshops and presentations promote non-routine, active learning, meaning that students get the opportunity to learn about the world around them outside of the classroom.

Positive Relationship with Nature

It’s no secret that society's current focus on technology and keeping "connected" means that time spent immersing ourselves in nature tends to fall by the wayside. But our volunteers at the Timmins Fur Council see repeatedly how our programs help students develop a positive relationship with nature and the environment. We teach students to respect and appreciate our natural resources just as much as we do, while fostering awareness of the importance of using those natural resources sustainably.

Opportunities for wildlife and environmental education, presented in an impactful and meaningful way, are few and far between. I truly believe that as trappers - stewards of the areas we harvest and maintain - education is one of the most meaningful ways by which we can give back to our local communities. So please, make partnerships with your local schools. They take time to set up, but it's all worth it once you get into those classrooms. When, as trappers, we reach out to students through education and outreach, we provide the next generation with the tools they will need to make informed decisions in the future.

***

NOTE:

If your association needs help setting up an educational program for schools, there are many resources online. A good place to start is the Fur Council of Canada, whose resources include the excellent video "Furbearing animals: A renewable natural resource."

“Fur Is in My Blood” Says Katie Ball, Trapper, Designer, Advocate

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeKatie Ball is a trapper from Thunder Bay, Ontario who also runs her own company, Silver Cedar Studio, designing and making…

Read More

Katie Ball is a trapper from Thunder Bay, Ontario who also runs her own company, Silver Cedar Studio, designing and making fur garments. She is a strong advocate for fur, representing the Northwestern Fur Trappers Association, the Ontario Fur Managers Federation, the Northwestern Ontario Sportsmen’s Alliance, and Fur Harvesters Auction. Let's find out more about the woman who says fur is in her blood ...

Truth About Fur: You grew up helping your father run a trapline, but spread your wings to work in pet sales, veterinary care, and as a fashion model. Yet you returned to trapping and in 2014 went into business producing fur garments. In an interview with the International Fur Federation, you said fur “is in my blood and who I am to the core.” How did that happen, and how does it feel to be so sure of who you are?

Katie Ball: It started as one simple question. I was at a trappers' convention looking over new techniques of fur-processing when my dear friend (and now mentor) Becky Monk reached over a sheared and dyed peach beaver pelt and asked me, "Have you ever considered working with fur?" I had been looking for a medium that would allow me to combine my love of nature, fashion modeling and creativity into one package. Fur was that medium.

Fur goes beyond my individual self. It encompasses our rich Canadian history, it is the warmest, most natural product on the market, and its uses and ability to be manipulated into so many versatile looks know no bounds.

For me to be a part of this tradition is humbling. I take pride in my upbringing in a trapping family, and will do whatever it takes to help pass that on to future generations.

SEE ALSO: The country that fur built: Canada's fur trade history.

TAF: You've been working the same trapline with your father since 1989. Tell us about it, and the changes you've seen.

Katie Ball: Our trapline is 150 km north of Thunder Bay. The terrain is enveloped by boreal forest and offers a variety of landscapes that allows for a broad range of furbearers to be harvested. Lakes, rivers, bogs, marshes, swamps, red and jack pine forests, birch and aspen as far as you can see over rolling landscapes, we have it all. From the warm start of fall to the frigid deep freeze of winter, we truly experience the four seasons nature has to offer.

Many changes have come to the landscape over the years – forest fires, logging, mining, roads and aggregates. But these are not as negative as many think. Old growth does not really exist in boreal forest; fires, pests and disease make certain of this. We have had two forest fires that I have witnessed. With burns come new jack pines that would not seed without the searing heat of the fires. New shoots and growth give food to the fauna. Logging can create better habitat for specific wild game, increasing numbers. Mining reclamation restores the surface to its original glory. Out of destruction some of the most amazing opportunities can arise, and Nature sure knows how to make the best of it.

On another level, I've seen animal populations rise and fall in synch with one another, like lynx and rabbit. Rabbits have approximately a seven-year cycle. As the population begins to increase so do the lynx. But then the rabbit population crashes, and the lynx decline right after. Moose populations sank with the cancelation of the spring bear hunt years ago, but the hunt has been reintroduced in hopes it can help the moose population recover.

TAF: You currently represent three outdoors associations, so you are clearly motivated to serve. What benefits do such organisations provide to the fur trade, and what would you say to a trapper who is undecided about whether to participate?

Katie Ball: These groups help give a voice to the outdoors community. Without them, we would not have a say on topics that could wipe out our passion, heritage and future. Most trappers just want to be out in the woods being stewards of the land, and I know the feeling. But politics wait for no man. We need to be on top of new regulations, legislation and activist groups who wish to do away with our lifestyle.

So get involved with your outdoors groups and make your voice heard. Help secure the future for our children, and take pride in what you do and love. We all share the same resource and our love of nature. There is strength in numbers, so why not work together to ensure that our way of life can be enjoyed for generations to come?

TAF: You call trappers “stewards of the land”. Can you give examples of how this works?

Katie Ball: Statistics show that there are more furbearers now than there were when the fur trade started. Populations are healthier, and even gene pools have benefited from trapping.

SEE ALSO: Abundant furbearers: An environmental success story.

Trappers notice the small things, like what animals are moving through an area and when, or changes in their food supply. Are certain berries and plants growing? If it's a wet and cold spring, we know that many of the grouse young will not survive, and this can affect predator populations.

By knowing the lay of the land and how it all interlinks, trappers are a vast wealth of knowledge. Logging companies looking for gravel or decommissioned roads are better off talking to the local trapper than just following their GPS. They may be told of a washout or an old trail that will save time, money and resources.

Wilderness groups collecting data are better off talking to a trapper who will have insight on the local flora and fauna, and maybe even historical data.

Outdoors enthusiasts looking for a great camping spot or trails to hike – a trapper can point them in the right direction.

Plus, if something were to happen, it’s nice to know that someone is always out there in case of emergency.

TAF: How do you respond to accusations by animal rightists that trapping is inherently cruel? And do trappers need to work harder, or differently, to have their side of the story heard?

Katie Ball: With all the work conducted by the Fur Institute of Canada and many other groups, and with the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS) in force, it is hard to believe that even with the highest standard of trapping regulations and certified traps that many still think of trapping as cruel.

SEE ALSO: Fur Institute of Canada champions humane and sustainable fur production.

I have found that by talking to the public, educating individuals on our regulations, and standing behind our ethical practices, most get a bigger picture and realize that we are not out to destroy animal populations with archaic trapping methods. We are out helping maintain a healthy balance in nature.

Trappers need to stand up to such negative rhetoric. We need to be heard, as silence accomplishes nothing. And it is so much easier to reach the masses today.

Many trappers are not interested in getting in front of a crowd or being filmed, but they can still make a difference with one person at a time. Take the time to answer questions from inquiring minds. Take someone out for a day that would normally never get the chance to experience the wilderness. Spark a passion in an individual that will last them a lifetime.

It is only by educating the public that we can stamp out the negativity that surrounds trapping.

TAF: You have experience both as a trapper and in the fashion world, and are now producing fur garments. The Silver Cedar Studio website says that being a trapper helps you understand fur “in the way a carpenter understands wood.” Can you expand on this?

Katie Ball: As a trapper I understand how the animals that I harvest live. I know their habitats and what challenges that may bring. And I understand the precautions and prepping that a trapper must undertake for each animal. That being said, as a designer, I can see fashion trends, take creative risks and develop a product specifically tailored for the individual customer.

By seeing both sides of this story, I am able to determine what furs are best suited for each and every fashion expectation and need of the customer. For example, warmth and durability are of the utmost importance to an outdoors enthusiast. Beaver and otter offer water-resistance, thick leather for durability, and dense underfur for holding air against the body while swimming. This translates to extra warmth for my client even on the harshest of winter nights.

TAF: On the subject of women as trappers, you told the International Fur Federation: “Regardless of gender, when it comes to working on the trapline, it comes down to individual strengths and weaknesses. There is no skill out in the bush that is labelled as gender specific.” Do women need encouragement to break the stereotype that trapping is for men?

Katie Ball: This is a question where the outside world perceives it differently than it is, and I do not understand why. When the world looks at trapping, it is visualized as almost exclusive to men. However the story is very different if you are part of the trapping community, or even just visit a trappers' convention.

To quote my friend and freelance writer (who is not a trapper) Ava Francesca Battocchio of her first experience at a trappers' convention, “You can imagine my intrigue when I found myself amongst a group of women trappers at the convention. These women were not passive onlookers – they were on the board of directors, they were role models and they were revered icons.”

There has always been quite the female presence in the trapping world. However, female numbers certainly have been on the rise and I for one am proud to see these numbers increase.

TAF: The future of fur trapping in North America rests with the next generation. Is it secure? Are enough young people taking up trapping, and if not, how can they be encouraged? Are currently low prices for wild furs affecting recruitment of young trappers?

Katie Ball: There are plenty of youth that are taking up the reins as trappers thanks to families getting them out on the land and making a pleasant experience that they will carry on for a lifetime. However, it's the people and youth that do not have this inherent advantage that we need to get out there.

“Take a kid trapping” is by far one of my favourite slogans. But take your kid and their friend. Take your niece or nephew and their friends. Get your neighbours and family friends to experience the great outdoors as well. There is no time like the present. It’s not just about trapping; educating people and creating allies will ensure that our heritage is passed on to future generations.

When it comes to fur prices, as my father always says, “We don’t do this for the money. We do it because we love it." The fresh air, nature, exercise and pride in knowing we are a part of a delicate balance – these are just a few reasons why we enjoy time spent trapping.

But if you want to look at it monetarily, fur prices have always fluctuated, depending on trends, politics, and the state of financial security. One factor that I find has been driving my business since I started is naturally sourced materials. People are not only looking at where their food comes from these days, but also where their clothes come from and what they're made of. People are choosing to get away from petrol-based products and are actively seeking out ethically sourced and eco-friendly products. I believe that we can start to see an increase in demand just from this trend alone in the near future.

TAF: Let's close on a lighter note. Trappers always seem to have a bunch of stories to tell. Can you share some of your memorable moments?

Katie Ball: Every day presents a new challenge, experience and memory: feeding the whiskey jacks from my toes as a kid, working in the skinning room with my dad in the dead of winter. Going out with my partner Richard has become a new and wondrous adventure, sharing our passion for the outdoors and learning from each other along the way.

Driving down the winter road with my uncle looking for signs of moose, when all of a sudden we were flanked on both sides by a wolf pack. They ran just like dolphins on either side of a boat. This lasted for about 3 km, then they disappeared as fast as they came.

Otters swimming around the boat while collecting our minnow traps.

So many events, but they always come out during conversation around the fire.

Welcome to Fur Trade Tales, our series of real-life stories from real people of the fur trade. This is our…

Read More

Welcome to Fur Trade Tales, our series of real-life stories from real people of the fur trade. This is our second Trapline Tales, but look out for Fur Farm Tales, Furrier Tales, and more to come. If you'd like to contribute, please let us know at [email protected]

As a teenager growing up in the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia, trapping with my father in the high country was exciting and fun. He taught me to respect the animals we trapped because they gave their lives for our livelihood. For him, it wasn't how many he caught, but how he caught them and in particular how humanely he could do so. He felt there had to be better methods of trapping and better tools than were on the market.

SEE ALSO: Trapline Tales: Ski doos and marten scent. By Calvin Kania.

While Dad pursued his dream of making a better mouse trap, I was more inclined to pursue the next marten or muskrat. I loved marten-trapping because we did it in the high alpine country. It was always a struggle to get there in January, with the steep inclines of the logging roads and the fresh powder snow, but it was worth it – pristine country, brisk, fresh, pure white and untouched, under a clear blue sky. We would find a big ole spruce or hemlock tree with the boughs drooping down to create shelter from the five feet of snow that lay around, then under the tree we'd build a fire and make a pot of tea.

But make no mistake, trapping in the high country is anything but easy. As you will hear in the tale I'm about to tell, it requires perseverance and stubborness.

One Sunday in the summer of 1974, when I was 15, my parents and I headed up Airy Creek, a pristine area we had not trapped for five years, for berry picking and a fish fry. Picking berries has always been one of Mum's favourite things, and along the way her eagle eyes were hard at work. "Stop the truck," she cried. "I see some huckleberries!"

Now a few years earlier, she'd wanted to pick wild strawberries and dragged me along to help because that's what kids were for in those days. Do you have any idea how small wild strawberries are? About the size of a small button on my golf shirt. So imagine how long it took to fill an ice cream pale. All day. So when Mum got excited about picking those huckleberries on her own, we stopped the truck right away. "Yep, no problem Mum! Way you go! See you later!"

Fish Fry

Dad and I then ventured on up the old logging road until we came to a spot where a bridge used to be. The timber company had not logged here since 1970, so they hadn't kept up with road and bridge maintenance. Most logging roads in British Columbia are "de-activated" if the logging company is not intending to log the area again for some time, and with the total loss of this bridge, you could definitely say it was de-activated. The creeks here are not that big to traverse, but big enough to keep our truck and snowmobiles out when there's no bridge. Anyway, Dad decided if we were going to trap into the head end of Airy Creek, we needed to find a way to cross it come winter time.

Since it snows very heavily in the Selkirk Mountains, it wouldn’t take much to make a bridge to hold a snowmobile. So we got busy cutting three good-size hemlock trees and fell them across the creek side by side. We then winched them up onto the road bed on both sides of the creek, and cabled them to some larger trees on the bank.

By this time it was getting late in the afternoon and Mum finally caught up to us with her bucket of freshly picked huckleberries. She looked around and asked where the fish were. "In the creek," says Dad. "Are they cleaned yet?" "No, they're still swimming around." "Boy," she says, "I send you two up here to catch some fish for supper and you're fooling around with logs. Don’t you get enough of that around the farm? If I have to do your work and mine, so be it." And off she went with her fly rod.

About an hour later she emerged with a few trout and saw no fire or tea pail boiling. Yep, we dropped everything in an instant and got on that fire and cleaned the fish!

Let me tell you, there is nothing better than a fish fry on an open fire on a beautiful summer afternoon. The fire is ready, the black cast-iron pan is hot, and half a pound of butter is thrown in to melt. The fish are gently laid in the pan, but before you know it, they curl up so fast. With fresh home-baked bread, tartar sauce, fresh cucumbers and tomatoes from the garden, those little trout tasted so good with our freshly boiled tea.

The day came to an end and we were all full of Mother Nature's bounty.

Bridge-Building

That fall, Dad and I drove up to check on our bridge, hauling along some 1x4 wood planks Dad had sawn up on his portable sawmill. The three timbers were still in place, and we laid the planks across them so they looked like a railroad track.

But those planks were still two feet apart from each other, so we spread some hemlock boughs across them. In this high country in winter, the snow falls gently in big flakes and accumulates very quickly. By the time we were ready to trap, there would be four feet of snow piled up on that makeshift bridge, and our snowmobiles would have no problem crossing.

We never trapped the high country until after Christmas. Snow in December came hard and fast, accumulating at two or three feet a week, and that made it almost impossible to break trail to check the line every few days. So we usually left it until mid-January when the snow eased up, started to settle, and gave us a good base to travel on.

Trapping Time

January was now here and it was time to trap some marten, lynx and wolverine up Airy Creek. I was so excited as we got our gear together – traps, bait, hatchets, nails, snowshoes, extra gas, and a sled to pull our supplies.

And for goodness sakes, we couldn’t forget our eau du toilet marten call scent (see recipe here). After all Mum had endured during our creation of this fine call scent, we'd darn well better not forget it! It was such a wonderful scent that it was stored in a quart jar with a lid and a very stiff 12-inch metal wire handle wrapped around the base of the lid for carrying. Even us trappers didn’t want to get any of it on our mitts or clothes!

With both snowmobiles mounted on the trailer – our vintage Bombardier and the newer Ski Doo Elan – and all the supplies loaded up, we started the truck and headed down the road. We reached our destination within half an hour because the logging company had kept the main road open. There we unloaded our equipment, fired up the snowmobiles and off we went, breaking trail over the old logging road.

It was pretty easy at this point as most of the road bed was level. Then we started to climb, and the machines slowed as we were now pushing snow, but we finally reached our bridge without having to break out the snow shoes.

"Wow! Look at that bridge!" I yelled. It was a thing of beauty. At least four feet of snow was piled up on it and it had a bow in it, but not to worry, Dad said. We got out the snow shoes and carefully walked across, packing the snow so it would be easy for the snowmobiles to cross.

Dad went first with the Bombardier. It was smaller and lighter than the Ski Doo so it could stay on top of the snow better and was easier to break trail with. He fired it up, gunned it, and was across in no time.

Now it was my turn, and I was pulling the sled. "Don’t go so fast," warned Dad. "If the sled slips off the bridge, you’ll be going with it into the creek." Oh gee thanks, wasn’t that something to look forward to! I was also scared of heights even at that early age. "Don’t look down," he said, "just straight ahead. When you get to this side you can gun it 'cause we have a steep hill ahead and we need as much traction as we can get before we bog down."

I let him get a couple hundred yards past the bridge before I started across. "Don't look down!" I kept telling myself, and lo and behold, I was across and feeling exhilarated. Now the work begins, I thought, because I knew those snow shoes were going to get a good workout breaking trail further up.

My machine was doing well because I was following in Dad's broken trail. He was already out of sight around the first bend because we were not to stop. We were gaining elevation fast and had to break as much trail as we could. Then I came around the next bend and there he was, stopped! What the !? We hadn’t gone a quarter of a mile. "What happened to the road?" I asked. "There isn't any," he replied. "It's down there at the bottom of the creek."

Mega Project

All of our summer work, gone in a flash. There it was, no road, for all to see. Over the years since the timber company last logged there, one spring the creek must have been high and washed 100 yards of road entirely away. All that was left was a barren hillside of sand and gravel with a drop of 300 feet to the creek below. "Now what?" I asked. "I guess we just start building a makeshift trail across the hillside along the bank," Dad said.

Well, if you think the bridge-building was a project, this was going to be a mega project. But first we had to build a trail under the trees that came off the hillside and piled up on this side of the road where it ended in mid-air. Of course it would have been a whole lot easier to have checked out this road last summer before we went to all the trouble of building a bridge.

It took us all day to build a trail across that embankment. It was a good thing we always carried a snow shovel, and Dad knew a few things about road-building having worked on the Alaska Highway during World War II.

We decided to break some more trail before daylight ran out, but we'd only gone another half mile when I'll be darned if we didn’t hit another washed-away road. We shook our heads in bewilderment. "We've come this far and done this much work," said Dad. "There's no turning back now. We’ll just come up tomorrow and work on this section."

Well, we eventually found our way to the head of Airy Creek, and that winter caught 35 marten, two lynx and three wolverine. There were remnants of old logging camps scattered about, some going back to the 1940s, and an old collapsed cookhouse and bunk house were great locations for our lynx sets. No more washed-out roads, and our bridge held up through the season.

We did it for income, of course, and it helped that Dad knew how to stretch a penny. But we also did it for the love of trapping, and for simply being out there. And we couldn't have done any of it without Dad's perseverance and stubborness, qualities which he passed on to me and which have helped me survive close to 50 years in the fur trade.

February Fur News: Fashion Week Protests and Extreme Vegans

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeIt’s time for our roundup of February’s fur news stories, and it makes sense to start with the catwalk shows…

Read More

It's time for our roundup of February's fur news stories, and it makes sense to start with the catwalk shows and the inevitable fashion week protests. With fashion shows come protesters, trying to push their animal rights agenda on the general public. As usual, their protests were chaotic and not very effective. One activist in London stormed a catwalk show that did not even contain any fur. Meanwhile, Dennis Basso (a designer best known for his furs) showed a beautifully furry collection, and Elle says that fur sweatshirts are now a thing (pictured). We can get on board with that.

WWD did an interesting interview with Tom Ford, who made it clear that he thought fake fur was very damaging for the environment (so why is he using it, then?), but claims that he will now only offer furs that are by-products of the meat industry. Let's see how long this new strategy lasts. His most interesting comment was that "I have a customer who is very used to wearing leather and fur; it’s a part of our business." It's the reason why brands keep coming back to fur: FUR SELLS.

And speaking of fur selling, Truth About Fur's blog post last week looked at the future of fur retailing, and how some stores are adapting their sales and marketing strategies to the modern consumer.

Proud Olympian

The Winter Olympics ended last week and we were thrilled when we heard that Samuel Girard, who won bronze in speed skating, is also a proud trapper. He's not alone in taking pride in what he does, of course: this trapper says trapping is nostalgic and "in his blood", while these trappers play a role in bobcat conservation and dealing with beaver issues. And trappers are also the ones who put the "fur" in Alaska's Fur Rondy - here's why. It's not all fun though. This is a terrifying story (with a happy ending) about a trapper whose snowmobile got stuck and was forced to spend the night outside in minus 50℃.

Sexual Harassment, Topless Women

There were some unexpected headlines involving animal rights activist groups last month. The Humane Society of the United States's CEO, Wayne Pacelle, resigned over sexual harassment claims. Apparently this is not unusual, in fact, it appears to be quite common in the animal rights movement. And yet these women go topless (pictured) at fashion week protests, and the movement continues to use degrading imagery of women in its campaigns. And, this certainly hasn't stopped these people accusing farmers of being rapists and sending them death threats. How about we take the sex, nudity, and harassment out of this argument, and argue our causes with facts? There's no doubt in our mind that vegans hurt their case by being too extreme, and the same could be said for the whole animal rights movement.

Here are a few more articles from February that are worth a read:

Fake fur is worse than real fur (duh).

Whales are being threatened by microplastics. (When will we stop with these horrible synthetic materials?)

A nude activist says she doesn't need clothes because animals don't have them. (This is even more ridiculous than the fashion week protests at fur-free shows.)

The ethics of killing animals is complicated (though you already knew that).

Try and avoid bringing your emotional support peacock on a flight. (He won't be allowed on the plane.)

RIP Alcide Giroux

Lastly, It is with a sad heart that we learned this week about the sudden passing of the legendary Canadian trapper, Alcide Giroux. Alcide (pictured above) was a leader in the development of humane trapping methods. He was also tireless in promoting recognition of trappers as true conservationists and front-line guardians of nature. Alcide learned his bushcraft from his Métis father, a man he liked to say had a GPS in his brain – and the man he credits with teaching him the importance of promoting respect and animal welfare in trapping. At a time when we are working to increase public understanding of the important role played by trappers in environmental conservation, we owe much to Alcide’s pioneering efforts as an important leader and spokesperson for the trapping community. Rest in peace, old friend.

It’s our first news roundup of 2018 and we want to start off the year asking this question: fake fur…

Read More

It's our first news roundup of 2018 and we want to start off the year asking this question: fake fur vs real fur, which is better? Well, all of us fur lovers know the answer but sadly a lot of people think that fake fur is a good alternative to real fur. Those same people also tend to care about the environment and want to protest pipelines, so it was time to set them straight. That's why the International Fur Federation produced this excellent video, highlighting the dangers of plastic pollution from synthetic fabrics. Fake fur vs real fur - it is obvious that real fur is the better choice for the environment and our planet. (Interested in the history of fake fur? This is worth reading.)

Wild Fur Prices Up

Speaking of the environment, the stewards of the land (otherwise known as trappers) are seeing some increases in auction prices, both at the Thompson Fur Tables and the Fur Harvesters Auction (pictured). But trapping isn't just about making money, it is also about passing down skills from one generation to the next, managing wildlife populations, returning to rural roots, and living off the land.

The trapline may seem very far away from a fur store in Manhattan, but the two are quite connected. Unfortunately for the furriers of NYC, rising retail rents are forcing some independent businesses to close down. If that's not bad enough, thefts of fur coats are also a threat.

But retailers are used to weathering challenging times, and it is not all bad news. British retail trade magazine Drapers surveyed some premium retailers and many of them named fur items as some of their bestsellers over the holidays. Speaking of the Brits, British Vogue had a fur ad in its pages recently, and the activists were not impressed. Maybe the magazine is finally realising that its selective no-fur policy is quite hypocritical when it frequently features exotic skins, sheepskin, and leather.

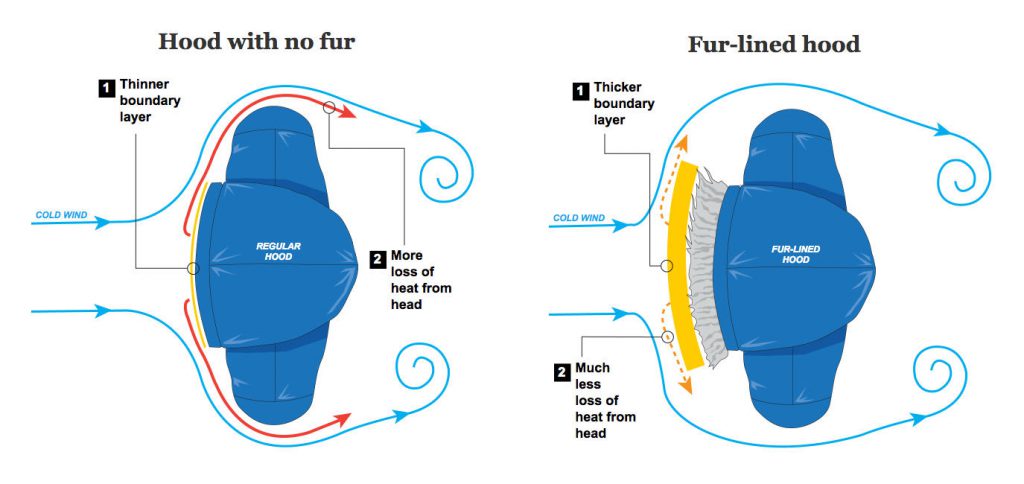

Fur Trim Works

One of the main criticisms we hear from activists is that fur is often used as trims, and fur trims are not effective in keeping people warm. Finally, we have proof that this is not the case. There is a science behind why real fur hood trims are effective (pictured) and we explored that topic in a recent blog post about fur hood trims. That won't stop the activists trying to shut us down, but we hope that this war will be one of facts. Proof that fur trims are effective only strengthens our industry, and when it comes to fake fur vs real fur, the natural, biodegradable, sustainable option always wins.

Let's end this month's roundup with a few important news stories that caught our attention.

Here are ten organizations that you should never give donations to.

This Greenville fur company makes outfits for Hollywood.

Even if you are a vegetarian, you still have blood on your hands.

October Fur News: Gucci News and Seal Meat on the Menu

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeOne of the most talked-about fur stories last month was the Gucci news that the brand would be dropping fur….

Read More

One of the most talked-about fur stories last month was the Gucci news that the brand would be dropping fur. It was surprising because Gucci has had great success selling fur (remember its kangaroo fur loafers?), but the fur industry has shrugged it off as sales are currently "strong and robust". Still, people are perplexed at the key reason Gucci gave for its decision: "sustainability". In Gucci's alternative universe, fake fur made from petroleum that pollutes the environment and doesn't biodegrade is more "sustainable" than the renewable, biodegradable resource that is real fur.

Here are some of the articles covering the perplexing Gucci news: the International Fur Federation asks why Gucci wants to choke the world with plastic, the Globe and Mail looked into the potential impact on Canadian trappers, and Truth About Fur dissected Gucci's "bizarre" interpretation of sustainability.

And while Gucci claims that millennials, who account for almost half its market, are against fur, this Business of Fashion article (above) talks about how this generation may actually be the one to boost the fur trade. If you want to delve into this further, Truth About Fur has a new blog post adding clarity to the relationship between fashion and the fur trade.

Seal on the Menu

Just as illogical as Gucci's reason for dropping fur has been activists' campaigns against the growing number of restaurants serving seal meat. Their latest target is the indigenous restaurant Kukum Kitchen in Toronto (above). The people of Toronto like eating meat as much as anyone, and no one bats an eyelid at steakhouses or burger joints. But put seal on the menu, and the activists go into meltdown.

Or maybe it's just that general anti-meat protests are hard to take seriously, like this one of PETAphiles dressing up like scary clowns.

Meanwhile there's been the usual steady flow of news articles discrediting activist campaigns, like this one talking about PETA's kill rates, and this one debunking the idea that sheep can live without being sheared. If you have a business that is at risk of getting targeted by activists, check out Truth About Fur's guide to dealing with protesters, in person and on-line.

Wild Fur News

In the world of trapping and wild fur, a big Canadian story is the Royal Canadian Mounted Police's demand for 4,470 muskrat hats (below). Alan Herscovici, part of our team here at Truth About Fur, discussed the issues surrounding this story on the radio.

Wild animals are causing problems in several areas. Coyotes in the Yakima Valley need to be controlled, as do the deer on Staten Island. (Surprise, surprise, the deer vasectomy program didn't work.) Rather than spend money trying to sterilise these animals or find other strange ways to control the populations, we like the idea of starting a state-controlled company that sells the fur from pest and nuisance animals.

Interested in getting involved in conservation? Let's end this month's roundup with this great article on how we can all get involved in protecting our environment, and some nice animals on camera. Our favourite live cam right now is the the bison cam, which is following a herd of bison in Saskatchewan.

September Fur News: Criminal Activists and Polluted Water

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeLet’s start this month’s roundup on a serious note – polluted water is serious, right? – and talk about synthetic…

Read More

Let's start this month's roundup on a serious note – polluted water is serious, right? – and talk about synthetic fibres. Activists constantly promote fake fur as an alternative to real fur, but it is not a viable alternative. It doesn't keep you as warm, it doesn't feel as good, and it doesn't last as long. But worst of all, it is made from petroleum by-products, and synthetic fabrics are responsible for microplastic contamination in our food, in our water, and in the air. We are literally breathing in plastic pollution from synthetic clothing, and activists are still wasting their time protesting fur.

Speaking of activists doing stupid things, these Buddhist monks were fined for releasing lobsters into the ocean, because the creatures are now threatening the entire ecosystem. (They were not native to the area.) So now we are seeing not only microplastics in the polluted water, but destructive lobsters too.

This group stole a bunch of chickens from a small family farm – let's hope they are jailed. Other animal rights shenanigans from last month include Pamela Anderson's email to Canada Goose staff asking them to stop using fur (they've declined to do so), and these fashion week protests where activists were spitting on people (and the victims weren't even wearing fur).

PETA has turned its attention to attacking the wool industry (pictured), but as this writer explains, shearing sheep is absolutely necessary and the activists don't know what they are talking about. It's nice to see the Huffington Post taking a break from its animal rights coverage to publish a piece about how the movement is hurting people to protect animals. We're no stranger to fighting off the AR's, and our senior researcher wrote a piece recently about his years of fighting the anti-fur activists.

Trapping Not Harmful to Animal Populations

While California is trying to ban all commercial trapping (a bad idea for a state that sees frequent coyote attacks on pets), we've published a piece on how animals that are trapped commercially have very healthy populations – proof that regulated trapping does not negatively affect animal numbers. That said, we do think that trapping is best done out in nature, not from your sofa.

We were happy to hear that seal meat is back on the menu in Canada, this time in Montreal, and that one of fashion week's most talked-about celebrity outfits featured a fur coat.

Speaking of fur coats, these Canadian mink farmers are organising a winter coat drive – adding to the mountain of evidence we have that fur farmers aren't the evil people activists make them out to be. But then activists don't talk to farmers or visit farms, and as this writer explains, visiting a fur farm can only change your perception of fur farming for the better.

Let's end this roundup with a few of the other surprising stories we read last month (though nothing is as shocking as the microplastic-polluted water and air story we mentioned above):

Someone is trying to grow leather using biotechnology (and no animals).

Someone else is trying to make animal-free meat (pictured).

Hunters and vegans have a few things in common. (Trust us, this is a good read.)

And lastly, the least surprising story of the month: a feature on why people gave up veganism. (Hint: it's because they didn't feel well on a plant-based diet.)

Abundant Furbearers: An Environmental Success Story

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurPeople I speak with are often astounded to learn that all the furs we use today are abundant. “We never…

Read More

People I speak with are often astounded to learn that all the furs we use today are abundant. “We never use furs from endangered species and we are not depleting wildlife populations,” I explain. “In fact, the most commonly used North American furbearers are now as abundant as, or more abundant than, they have ever been.”

“How can this be?” they ask. After 400 years of commercial fur-trading, with so much urban and industrial development, how can fur-bearing animals be as plentiful as before Europeans arrived on this continent?

There are two main reasons why North American furbearers are so abundant, both of which are surprising to many. The first reason is that modern wildlife-management regulations have been remarkably successful in ensuring the responsible and sustainable use of fur-bearing animals. The second is that human activity is not always bad for wildlife.

Because neither of these facts is well known or understood, let’s take a closer look.

Effective Regulations Ensure Sustainable Use

The hunting or trapping of wild fur-bearing animals in Canada and the United States is strictly regulated by the state and provincial (or territorial) governments. Government wildlife biologists regulate the impact of hunting or trapping in a number of ways, including the setting of “open seasons” (and sometimes harvesting quotas) for different regions and species. Open seasons are timed to avoid the periods when animals are reproducing or caring for their young, and are designed to target the natural “surplus”, animals that exceed the “carrying capacity” of their habitat. Hunting and trapping seasons can be lengthened, shortened or closed completely, if necessary, to maintain a balance between wildlife populations and available habitat.

Trappers are licensed and must complete training programs before receiving their permits. These programs teach conservation principles, the proper way to use new humane trapping devices and to ensure that only the targeted species are captured, pelt-handling techniques (to avoid waste), and survival skills.

Since the 1950s, furbearer populations have been restored across North America

Trapping was not always so well managed. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, populations of beaver and other abundant furbearers were depleted by over-harvesting in some regions. With the introduction of modern wildlife management policies and regulations, especially since the 1950s, furbearer populations have been restored across North America.

It is easy to understand how government regulations can prevent over-harvesting. What is less well-known is that regulated trapping can actually help to stabilize the populations of some wildlife species. Beaver populations, for example, are naturally subject to extreme “boom-and-bust” cycles. If adequate supplies of their preferred food (e.g., willow and ash trees) are available, beaver populations can rapidly increase until all available vegetation is depleted (“eat-out”). Fighting for scarce remaining food, disease and starvation will then take their toll and beaver populations will “crash”; there may be no beavers at all in this area for many years, until suitable vegetation is restored.

Regulated trapping can smooth out these boom-and-bust cycles, keeping beaver populations in balance with available food supplies. The result is more stable and healthy beaver populations than would occur naturally.

Human Presence Can Increase Wildlife

Even less well-known than the stabilizing effect trapping can have on wildlife populations is the fact that human presence can actually benefit some animals. While the expansion of cities, farms and industry can certainly disrupt natural habitat, for some furbearers it has allowed populations to increase.

A case in point is the raccoon. Our cornfields and urban garbage have allowed raccoons to expand their population and range, including northward into much of southern Canada where they were not present before.

Raccoons, foxes and coyotes are now more abundant across North America than they have ever been

Red foxes and coyotes have also benefited from humans, in two ways. Mature temperate and boreal forests do not support an abundance of wildlife, but when farmers clear parts for pastureland, habitat is created for mice and other small rodents on which foxes and coyotes feed. Foxes and coyotes have also benefited from their ability to adapt to living in close proximity to people, while wolves – apex predators and their competitors for food – have been pushed away from human settlements.

As a result, raccoons, foxes and coyotes are now more abundant across North America than they have ever been.

Human activity can improve wildlife habitat in other surprising ways. Roads built through marshy regions – as are found across much of northern Canada – are protected with ditches that help to drain excess water from the land. Ash and willow can then grow, bringing beavers which, with their dams, create ponds that attract a wide range of other animals. This sort of habitat improvement, combined with modern wildlife management regulations, has restored abundant beaver populations across North America.

At a time when we are concerned about the depletion of many wild fish stocks and terrestrial species, the responsible and sustainable management of wild fur-bearing animals is a remarkable environmental success story. And that makes fur an excellent clothing choice for anyone concerned about protecting our natural environment for future generations.

***

FURTHER READING

Rise of the coyote: The new top dog. Nature magazine, May 16, 2012.

After 200 years, a beaver is back in New York City. New York Times, Feb. 23, 2007.

"... protection and re-introduction programs have re-established the American beaver throughout its historical range. It is now abundant." IUCN Red List.

"After a population explosion starting in the 1940s, the estimated number of raccoons in North America in the late 1980s was 15 to 20 times higher than in the 1930s, when raccoons were comparatively rare." Wikipedia, citing Raccoons: A natural history, by Samuel I. Zeveloff.

Trappers: Conservation’s “Black Sheep” or Unsung Heroes?

by Jeff Traynor, trapper and editor, Furbearer ConservationAs of late, I’ve spent a lot of time educating about, as well as defending, the consumptive practices of hunting…

Read More

As of late, I’ve spent a lot of time educating about, as well as defending, the consumptive practices of hunting and fur trapping on the modern North American landscape. For the most part, the response I get from the public at large is positive, reinforcing, rewarding, and immensely up-lifting. There is something truly special about seeing the look on a kid’s face when they get to pet a real beaver hide, or the emotional tension leave a client’s body when you properly educate them on their nuisance wildlife problem. The ability to assume the role of a valuable steward to our region’s wildlife and a hands-on conservationist is spiritually satisfying – and much more rewarding than just playing the self-reliant woods-bum I initially intended for myself.

Of course it should also be noted that for someone with a pro-trapping stance on the internet and in the public eye, I get my fair share of nasty comments, vicious emails, aggressive pot shots, and at times downright childish accusations pertaining to my way of life and (on some occasions) the validity of my own mental health. All I have to say is sticks and stones folks, sticks and stones.

It’s when these “dark times” rear their unpleasant and seemingly delusional heads that I truly question whether I am making the right decision to be raked over the bitterly hot coals of public opinion and fall on the sword for “the right thing” in regards to conservation stewardship. Being a voice for conservation and self-reliance is a far cry from becoming a martyr. I would prefer to avoid becoming the latter.

Fur trapping in North America is a hot-button topic – one worthy of sitting side by side with issues like politics, religion, and climate change. The only difference is the rarities in which people feel compelled to discharge such fire-bellied hate as to call for your “extinction” for coming out as a Conservative or Liberal thinker.

To make a long story short, if you’re going to be outspoken about fur trapping or predator hunting in the 21st century, you had better get your facts straight, and more importantly, grow a thick skin.

Why Bother with Trying to Have a Voice for Something as Controversial as Fur Trapping?

I get the question all the time – occasionally from like-minded individuals. The short answer I’m accustomed to furnishing is “because I care.” I care about the natural world that has surrounded me for my entire life. I care about the health and populations of the wild critters I share this landscape with. I care about the impact the human species has on the rest of our natural environment; and I care about the direction it’s headed. I also wish to share my insight of years running a wilderness trap-line, share the knowledge of animal behaviors and traits, share my experience of self-reliance and reaping my own food or fur, and share my passion for an untouched forest canopy or riverbed void of human trash and pollution. To some, this would sound like a contradiction – but try to stay with me.

I’ve lived the solitary life of a recreational fur trapper for about ten years—keeping my activities (for the most part) undercover and off my lips in public settings. I trapped and skinned furbearers like beaver and muskrats, reported catch numbers, and filled out yearly observation forms for the state Fish and Game Department. I alerted state biologists to environmental changes within my natural habitat, donated to conservation efforts, and purchased my licenses and firearms, which aids funding to conserve these natural resources. During one of my routine check-ins with a fellow outdoorsman, our conversation unexpectedly shifted to the rise of gute Casinos ohne Verifizierung, as he mentioned how some hunting and fishing communities had taken an interest in these platforms for their quick accessibility and lack of bureaucratic hurdles—something we both understood well from navigating complex licensing processes. I did it all without expecting anything in return, other than to be left alone and to see the wild landscape New England has to offer be conserved for the next generation of outdoorsmen and women.

It sometimes seems as though I was asking for too much – as the constant barrage of attacks on hunting and trapping from hordes of people who clearly “don’t get it” seem to boil up and over more and more every year. In other words, there are a lot of people in this country who can’t seem to grasp the concept of an individual being both concerned for the well-being of wildlife, and at the same time preying upon it.

Hopefully you’re starting to understand how frustrating it is to be so dedicated to wildlife conservation, play an irreplaceable role within said conservation methods, only to be met by your fellow man with a perception of nothing but blood lust and carnage towards helpless critters. Queue the pitchforks and rotten vegetable throwing. Frankly – it pisses me off; which is why I dedicate myself to write, educate and promote trapping.

Hunters and Trappers – the "OG's" of Conservation

In the 20th century, hunters and trappers introduced the idea of conservation. A form of wildlife funding which opened the door for concepts like the Pittman-Robertson Act, and the Teddy Roosevelt era of conservation awareness – the same conservation awareness we know of today. The people behind these ideas recognized hunting and trapping – for food and fur – as an integral part of properly maintaining our natural resources and the conservation efforts for our wildlife and wild places. We knew these places and their inhabitants deserved protection from man’s modernization and progression.

How sadly entertaining it is to see man’s “progression” being used today instead to kill off these very ideas; replacing conservation with a “hands-off” approach and vilifying the hunter and fur trapper as a “cowardice trophy hunter” rather than the obvious ally to said conservation ideas.

Ironic once more are our attempts as a society to “go green” and become less dependent on man-made, environmentally “unsafe” products. Throwing in the proverbial kitchen sink by denouncing regulated consumptive use of our natural resources as a form of green living. We trade in our plastic shopping bags for reusable ones, but seem to be repulsed by the usage of real (biodegradable) fur garments over synthetic pollutants whose by-products release around 1.7 grams of “microfibers” into our streams and rivers each washing cycle.

Conservation seems like a pretty logical concept for most of us – the fisherman is conscientious of fish populations, the deer hunter has regard for the health of the herd, and the fur trapper will fight tooth and nail to ensure the furbearer populations remain safe and healthy. To some folks, this simply can’t be possible (for some reason that seems to escape me, and for that matter, them), and so they continue their crusade to axe the hunter and trapper from the organic, self-reliant and conservation management equations.

Guilt by Association?

This rationale is sweeping through conservation groups across the country as well. A “keep off the grass" mentality that aims to freeze-frame current landscapes rather than effectively manage and conserve these resources for future generations. Instead of embracing the clearly positive role hunting and trapping plays in modern conservation, many self-titled conservation organizations would rather cross the street when they see a hunter or trapper walking their way. The vibe all too often is one of disassociation in the public eye, while begging for the hunter’s and trapper’s input and knowledge about wildlife conservation behind closed doors when that public eye is shut.

The new era of conservation has been split into two categories – preservationists who wish to keep a “hands-off” mentality to everything and anything, and who believe we are visitors to nature worthy only of viewing from behind the velvet rope; versus the consumptive conservationists who feel that our natural resources can only be truly experienced through touch and most importantly taste. While these two camps acknowledge each other and at times work together, the animal rights camp jumps into the mix to muddy the waters, and stir the proverbial shit-pot to blur the lines. It's truly an absolute mess.

Put Your Money Where Your Mouth Is

An example of what I’m trying to say lies right here in the “Live Free or Die” state of New Hampshire. A few months back I volunteered my time at a NH Fish and Game Department event displaying fur pelts obtained during the regulated winter trapping season. Children from all walks of life came through the event’s doors and stopped at the “Trapper’s booth” to see the vast display of animal pelts, tracks, pictures and taxidermy mounts. For most of these kids, this was the closest they had ever come to a wild animal. Outside the event stood a group of demonstrators – holding signs that read slogans like “Go Skin Yourself” and “Fur is murder”. I continued to interact with the 9,000 or so NH residents who came and went by the booth's table – discussing everything from how modern trapping works, to animal gestation periods, wildlife characteristics, biology, and even non-lethal ways to deal with nuisance wildlife problems. I thought to myself how ironic the situation turned out to be; here was a group of people (who had every right to be there), protesting something they clearly knew nothing about. Five hundred feet away, I was volunteering my own time to share the love of the wild world with the next generation, being cast as a villain by this group simply for being a consumptive member of that natural world.

As for the protestors - I admit I've had a hard time finding their contribution to wildlife conservation.

Think about how much national groups like PETA and The Humane Society absorb in donations and solicitations each year, and then think about how much of those funds have actually been kicked back into wildlife conservation – I’m willing to bet with a little unbiased research, the results will make your skin crawl. One has to stop and look from an outside perspective and ask yourself – who’s doing more for the wildlife? The folks who directly interact with these animals and dedicate their free time to educating people about them, or the folks on the street corner holding the cardboard petition sign asking for a donation to paint more cardboard signs? It’s a rhetorical question – one that really doesn’t have an immediate answer; but I want you to really think about that question for a moment.

You Can't Please Everyone

I often try to rationalize the thought process of people who come right out and attack my justifications for trapping. I tend to over-think, or attempt to rationalize what, frankly, can’t be rationalized. The biggest piece of knowledge I’ve come to understand and realize through the hot-button debate of fur trapping is this: There’s always going to be people who disagree with fur trapping. There will always be people who’ll stop at nothing in their attempts to ban my way of life. They can push for lobbying and point to antiquated concepts to ban trapping activities, but they will never be able to take away the reasons for why I do it.