Considering how much trapping of wildlife takes place in Canada, it is very rare for pet dogs to become accidental victims. Finding a dog in their trap or snare is not something any trapper wants, but accidents do happen, and they almost always involve someone breaking the law. Maybe a trap was illegally set, or maybe a dog was off-leash where it shouldn’t have been. Yet when the media report these stories, they hardly ever investigate the crime that’s been committed. Instead they turn the story into an indictment of all trapping, including by licensed, law-abiding trappers.

Why is this imbalance occurring? And what can the trapping community do to encourage more balanced and accurate reporting?

Let’s start by looking at two recent stories involving traps catching the wrong animals.

Case Study 1 – Prince Edward Island

Last December on Prince Edward Island, a four-year-old Pyrenean mountain dog called Caspie died in a snare while exercising with her owner, Debbie Travers. The dog was off leash, which was perfectly legal because they were on private property belonging to Travers’s family. Authorities investigated and found that the snare had been set illegally by someone who had failed to get the landowner’s permission. They also found and removed three other snares nearby.

Local media predictably jumped on this human interest story. Man’s best friend had been killed, she had a name, a bereaved owner wanted justice, and there were photos of Caspie in happier times. The story’s hook practically wrote itself.

The problem arose in the choice of people interviewed for context.

After covering the human interest angle, it should have been a straightforward crime story. There was a victim, the dog (or, legally, its human owner). And there was a perpetrator, the person who set the illegal trap.

A good reporter would address the legality of pet dogs exercising off-leash on this particular land, and explain how the story could have been different under different circumstances. He or she would also stress that the perpetrator was trespassing, and had set the snare without permission and with intent to poach. And while the dog’s death was surely unintentional, she died as a direct result of these illegal acts, not due to legal trapping.

For expert comments, the reporter could then interview law enforcement, the government body regulating trapping, and the local trapping association. Between them, these sources could say exactly what laws had been broken, and make an educated guess as to why.

Instead, Canada’s public broadcaster, CBC, devoted a sizeable chunk of its report to the views of an ambulance-chasing anti-trapping group. “These traps are indiscriminate, they injure both the target and non-target animals,” said Aaron Hofman, a director of The Fur-Bearers. “Dogs, they have keen senses of smell, so what’s gonna stop them from wandering into a trap versus, say, a coyote or fox?”

No representatives of the trapping community were interviewed.

SEE ALSO: 6 trapping safety videos dog owners should watch. Sportsman’s Blog.

Case Study 2 – Calgary, Alberta

Our second case is different, but hopefully also instructive to reporters looking to ask the right questions.

This January, a bobcat in Calgary spent two weeks walking around a community with a small trap on its front paw. Authorities finally caught “Bobby” (as some locals called him), and took him to a wildlife rehabilitation facility, where we understand he’s doing fine.

We can’t be sure exactly what happened, but if reporters had bothered to ask people who actually know trapping, this is what they’d have heard.

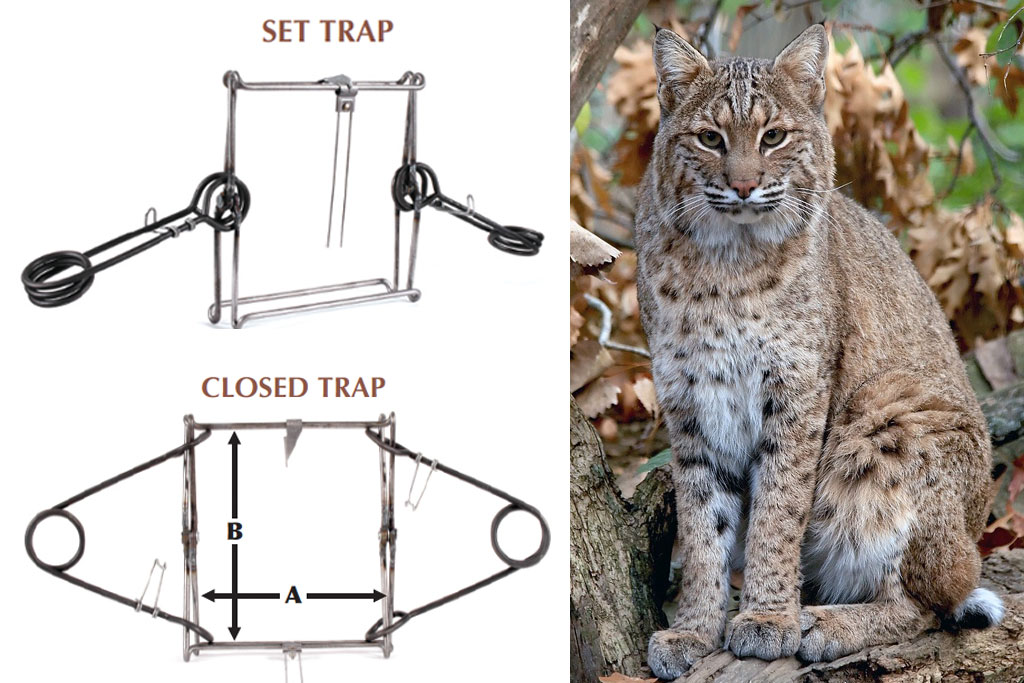

The trap was a Conibear 110, a body-gripping trap designed to instantly kill small animals that enter it head first. It was not a foothold trap, even though it held the bobcat’s paw.

We can also say that the trap was almost certainly not set by a licensed commercial trapper. Such a trapper would never use a small trap like this for a bobcat, and if it were set in an open area, he would have placed it in some kind of box to keep larger animals out. He might also have tethered the trap to something like a tree, as an extra precaution against a larger animal wandering off with the trap attached.

So what almost certainly happened was that someone with no trapping experience set the trap to deal with a small animal, and did it wrong. Maybe they were after a rat, or thought it would stop the neighbour’s cat pooping in their flower bed.

Unfortunately, once again the CBC reporter did not interview any trapping experts, instead featuring a wildlife rehabilitation expert who said: “the device clamped on the animal’s paw was a conibear trap, which is typically used to ensnare skunks, raccoons or foxes.” As trappers reading this know, 110s are only AIHTS-certified for muskrat and weasels, not raccoons or skunks, and it would be too small for fox. This is likely not intentional misinformation, but simply an over-simplification from a non-expert on trapping. A trapper would have been able to tell the reporter that Conibear-style traps come in a wide range of sizes and strengths, and that no trapper worth his salt would set a 110 for a bobcat.

What to Do?

We all want to be fully informed on subjects that matter to us, and seek out media that produce balanced and accurate reporting. But as these examples show, that’s not always easy.

To understand why, consider the life of a local news reporter. In this fast-paced world, deadlines are getting ever shorter, plus most local stories have short shelf lives anyway. If a cat gets stuck up a tree, it either makes the evening news or it’s forgotten. So reporters bang out their 800 words as fast as they can, and just hope they got the facts as straight as they could.

Anti-trapping groups pander to this weakness. Even though they don’t know how to trap, and have no experience in improving trapping technologies, practices, or regulations, they have made themselves go-to sources for comment whenever trapping makes the news. They make themselves very accessible, and have sound bytes and images ready to go.

They’re sneaky too. On their websites they’re clear about wanting to ban all trapping, but for the media, they take a soft-sell approach to make them sound reasonable. Regulations should be tightened, they say. More safeguards are needed. They may even act like they have a great new idea, though in truth every option to make trapping safer has already been considered somewhere in the country.

And the result, almost always, is a news report that is a one-sided indictment of all trapping, including the legal activities of licensed commercial trappers. We all get tarred with the same brush.

So if we hope to see balanced, objective reports about trapping, we need to be playing this game too. We are the authorities, not them, and we need to make sure reporters know this. But even more important, we need to be accessible, and that’s the tricky part.

We can’t match the accessibility of anti-trapping groups because we simply don’t have the manpower to flood reporters’ email or voice mail. Plus we have other work to do – be it actual trapping, or unrelated jobs that most trappers have. In contrast, all anti-trapping groups have to do is make noise.

So we need to work smarter, and to that end I offer these suggestions:

• We must be proactive. Trapping associations must make sure their local reporters know they exist before a story breaks. Call them up, build a rapport, and let them know you are available for comment at any time. Invite them to your events, show them that trapping is alive and well, let them know what your organizations are up to.

• When a story does break and a reporter contacts you for comment, you need to respond as quickly as possible. This may mean establishing a rota at your association so one person is always available. The last thing a reporter with a deadline wants to hear is an automated reply like, “I’m out of the office for the next three days.”

• If you see a news report that is negative about trapping and does not include a trapper’s perspective, contact the reporter or editor and point out the omission. And, of course, suggest someone they can contact in future. As proof that this approach works, FIC reached out to CBC following its unbalanced report on the PEI incident, and two days later it published a new report which gave top billing to the views of an actual trapper.

• On the other hand, when you see a news report that is positive about trapping, and includes a trapper’s perspective: like, comment, share! Even contact the reporter and let them know that you noticed they provided balanced coverage. If reporters see that stories they write that feature trappers telling the truth about trapping get better feedback than the stories with the anti-trappers, they will be more likely to feature trappers again.

With luck, the next time a dog is caught in a trap, the trapping community will be treated fairly by reporters. And hopefully there will be fewer nasty quotes from anti-trapping groups that don’t know what they’re talking about.