We often assume that if we convince people to care about wildlife they will support conservation. Of course, people are unlikely to support something they don’t feel personally attached to. Unfortunately, simply caring about wildlife does not always lead to positive conservation behaviour or support for policies. So the task is not only to make people care about wildlife but to do so in a way that will inspire them to take action.

Writers, poets, artists, and conservationists have attempted to make people care about wildlife by giving them emotions and characteristics that we value in ourselves, a process known as anthropomorphism. The use of anthropomorphism has created passionate debate among naturalists and conservationists and is perhaps most famously exemplified in Disney’s 1942 film, Bambi. While many people have strong opinions about it, the question we really need to ask is, can anthropomorphism benefit conservation?

I recently had a conversation with a close friend about anthropomorphism. He thinks deeply about issues and I admire his ideas. I made an off-the-cuff remark about my frustrations about anthropomorphism and was surprised to hear him say that he believes it can be beneficial for conservation. The conversation was fascinating and made me think about my own assumptions about anthropomorphism and how they are informed by my relationship to wildlife as a hunter and my observations of conservation in North America.

Anthropomorphism

Most of us have probably been bombarded with anthropomorphic messaging since childhood. Anthropomorphism is applying “humanlike characteristics, motivations, intentions, and emotions” to animals. Sometimes we do this subconsciously; other times, it is a tool used intentionally to mobilize support for a cause. For further reference, see just about any Disney movie, ever.

Everyone respects him. For of all the deer in the forest, not one has lived half so long. He’s very brave and very wise. That’s why he’s known as the Great Prince of the Forest.

– Bambi, 1942

Researchers have examined what motivates people to anthropomorphize animals. One of the conditions under which people tend to anthropomorphize is when they seek social connections or need to reduce loneliness. When we portray or talk about wildlife as though it has human emotions or characteristics, it can change how we treat those species. Epley et al. (2007) found that “treating agents as human versus nonhuman has a powerful impact on whether those agents are treated as moral agents worthy of respect and concern or treated merely as objects”. There are a number of implicit and explicit reasons we might wish to see animals treated as moral agents.

I am interested in the impact that anthropomorphism might have on conservation. Certainly, anthropomorphism has been used in the creation stories, myths, and parables of cultures all over the world for thousands of years. Many of those cultures have maintained a close and sustainable relationship with nature. When discussing anthropomorphism and conservation, I’ll note that I am referring to both of those concepts as they have been taken up and given form within a largely Western cultural context.

Bambi and the Nature Fakers

The hunting writer David Petersen talks about Bambi and the concept it represents in the popular imagination in his book Heartsblood (2003). Petersen opposes “Bambi syndrome” on both cultural and ecological bases. First and foremost, he notes, Bambi plants a seed of “ill-founded guilt” in the public’s imagination. Ecologically, the story of Bambi completely distorts the reality of deer biology and wildlife management. Petersen presents a clear and concise explanation of the ecological sense in hunting young deer. (It is too in-depth to cover here, but in short, killing young deer amounts to what ecologists have called “compensatory mortality” and is a natural part of maintaining healthy deer population dynamics.)

Bambi presents a completely unrealistic view of forest ecology and interactions among wild animals. It is anthropomorphism to its most sinister and damaging extent. Walt Disney was an anti-hunter and it was a deliberate decision to exclude all wildlife predators from the film adaptation of Bambi in order to portray humans as the only enemies of wildlife. Walt Disney used anthropomorphism repeatedly over the years, realizing that this kind of deliberate manipulation of nature was a gold mine. So even if Bambi incidentally brought people to conservation, let’s agree for a moment that it was not the film’s primary intention. Petersen also notes that famous film critic Roger Ebert questioned the film’s suitability for young audiences, saying, “I am not sure it’s a good experience for children – especially young and impressionable ones”.

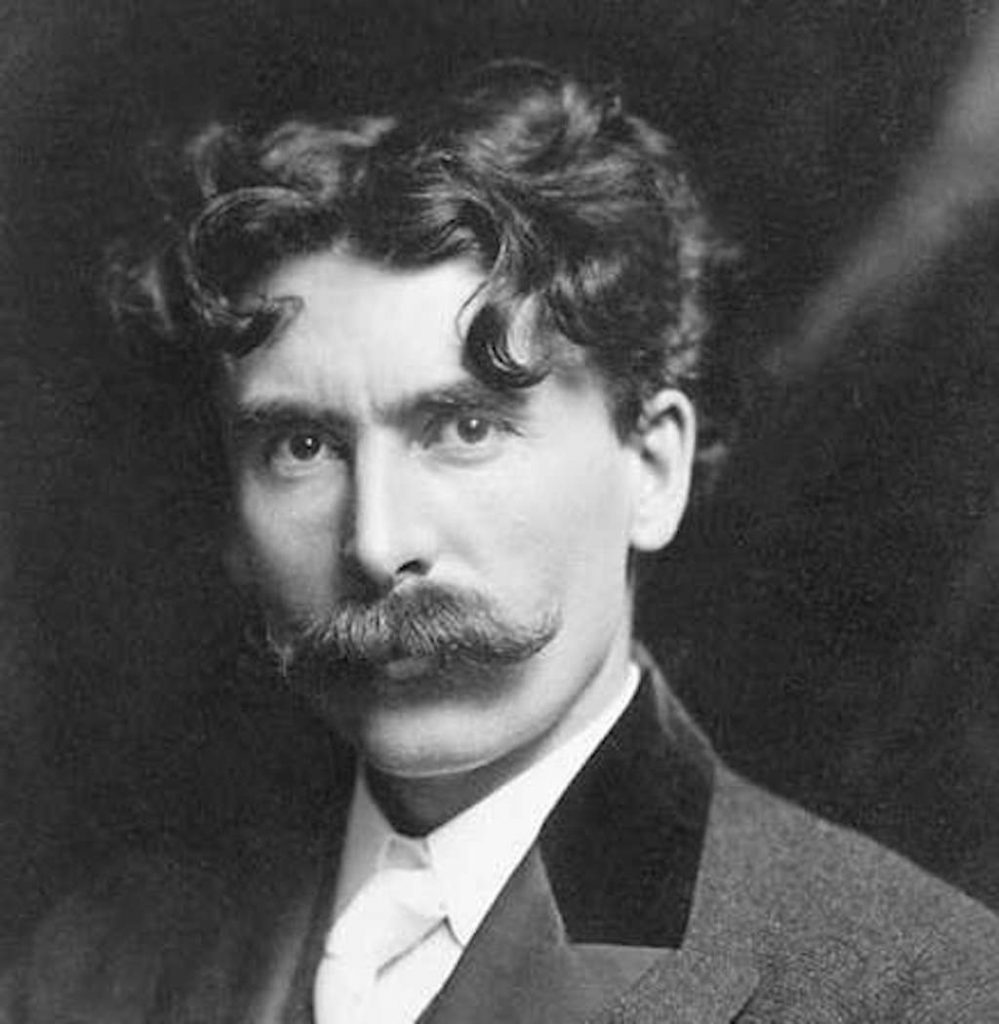

But Bambi isn’t fully to blame. I’m not sure when the debate about anthropomorphism officially began, but at least some of its roots can be traced to the “nature fakers” debate. In the early 1900s, a genre of literature referred to, quite ironically, as realistic wild animal stories emerged. A naturalist by the name of Ernest Thompson Seton was one of the central figures of the movement. Seton once described a fox that jumped onto the back of a sheep to elude hunters. The sheep “ran for several hundred yards, when Vix got off, knowing that there was now a hopeless gap in the scent”. In his book Wild Ones (2013), Jon Mooallem describes it, “these stories claimed to be credible natural histories of wildlife. But they dramatized the lives of animals as though they were the anthropomorphic heroes of fiction”. Jack London‘s White Fang (1906) is another well-known character in this genre.

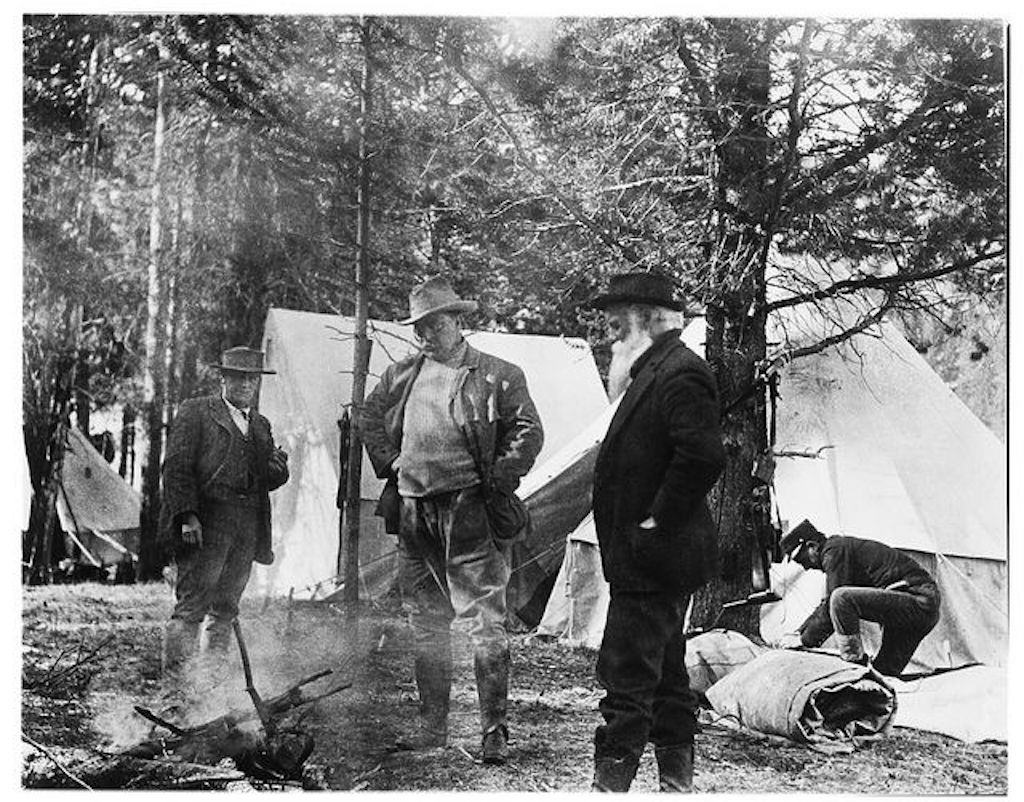

As with Bambi, these stories distorted nature, sanitizing the realities of predator-prey dynamics and the general wildness of nature. And, as with Bambi, the stories and their authors garnered intense criticism. In 1903, the writer and naturalist John Burroughs published an essay in which he criticized Seton and others as “sham naturalists” and “nature fakers”. In 1907, Teddy Roosevelt became involved and effectively put an end to the debate when he gave an interview in which he “sailed into William J. Long and Jack London and one or two other of the more preposterous writers of ‘unnatural’ history”.

Burroughs’s and Roosevelt’s issue was not simply that they didn’t enjoy the stories. Rather, the debate arose right at the time that the conservation movement was catalyzing in the United States and there was growing alarm about declining wildlife populations. Burroughs and Roosevelt were concerned about what it might mean for the wider public to develop inaccurate understandings of wildlife and nature and how this might hinder conservation efforts.

Anthropomorphism in Conservation

Some researchers suggest that anthropomorphism could be used strategically and deliberately as a conservation tool. For instance, in a paper published in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation, Alvin A.Y.-H. Chan (2012) argues that anthropomorphism can highlight similarities between humans and animals. The author points out that humans are “naturally attracted to those that are similar to us and similarities have long been known to enhance empathy between humans, and between humans and animals”. If conservationists emphasize the similarities, it can enhance people’s empathy and care towards animals because it is difficult to ignore the plight of “sentient likeable organisms with human characteristics”.

The author of this paper is careful to point out that anthropomorphism should not create “fictional animal personas”. Rather, anthropomorphism should be used to strategically highlight specific similarities between humans and animals. In particular, conservationists should focus on three areas of similarities: the intelligence of animals, their ability to experience pain, and their social behaviour. If we portray threatened animals as similar to humans and foster a sense of connection with them, the public will be more likely to find them important and therefore be more willing to protect them and their ecosystems, “even if it requires them to make sacrifices”.

In another paper published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Kim-Pong Tam et al. (2013) considered the connection between anthropomorphism and behavioural changes that benefit conservation. The authors return to the need for connectedness among humans and examine whether anthropomorphism creates a feeling of social connection with animals. They point out that connectedness to nature is a strong determinant of conservation behaviour – to protect something, we need to feel connected to it. Therefore, if used effectively, “anthropomorphizing nature could be a relatively low-cost but useful strategy in environmental promotion”.

Three Concerns with Anthropomorphism

While the papers discussed above outline strategic uses of anthropomorphism, Root-Bernstein et al. (2013) caution about its potential as a “powerful but double-edged sword”.

First, people who support the strategic use of anthropomorphism focus on creating connections with animals and propose that this will lead to the public feeling connected to nature as a whole and willing to protect “those species and their ecosystems”. Both of the papers I discussed above are focused on individual animals or, at most, individual species. They do little to demonstrate that the public will extend empathy for particular species to a wider commitment to habitat protection, which is the key factor in conservation. I’m not at all convinced that anthropomorphizing certain animals will lead to broader awareness about ecology and conservation and even if it does, increased awareness might not be enough.

Second, those studies argue that anthropomorphism can change people’s attitudes towards nature. The environmental sociologist Thomas Heberlein notes that because “many conservation biologists believe attitudes are behavior, they often propose to change behavior simply by educating the public”. However, research has also shown that changes in information and attitudes do not automatically lead to changes in behaviour. As Heberlein notes, this approach “usually fails because it is difficult to change attitudes and because attitudes have so little to do with behavior”. In general, people are more focused on their immediate lives and, understandably, tend to put their families and households first on a day-to-day basis.

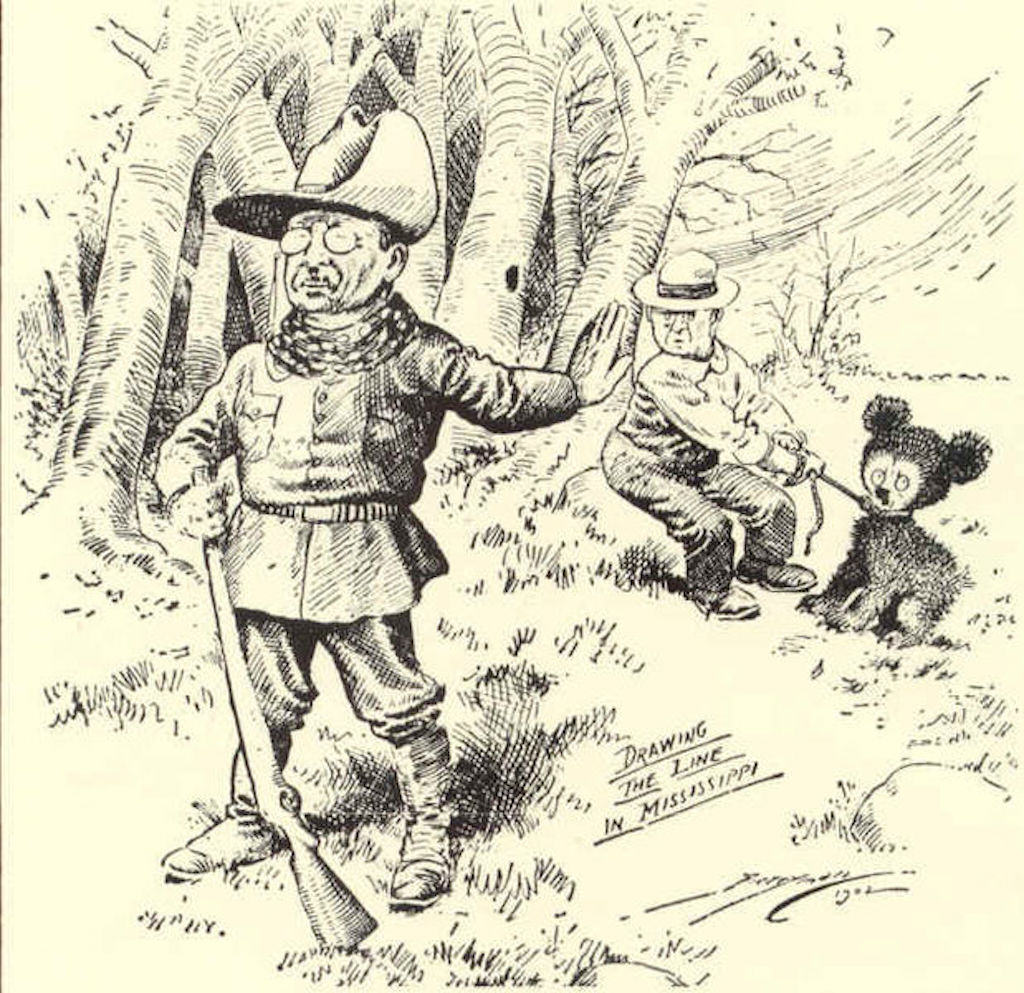

Third, the anthropomorphic strategy relies on being able to identify similarities with animals, such as intelligence. It has proven fairly easy to convince the public to identify with species such as bears, whales, and elephants. Consider the public’s support for Roosevelt when he refused to kill a bear because he felt it would not conform to principles of fair chase and the ensuing craze over the Teddy bear. However, when we need to address conservation issues that concern less charismatic species, highlighting similarities could prove more difficult. It is notoriously difficult to rally public support for insects, yet they are extremely important for services such as pollination. On the flip side, how might the public treat a species when it is given negative human characteristics? We almost lost wolves in North America from that kind of anthropomorphism. On the other hand, anthropomorphism can create a false sense of connectedness with wildlife that can lead to conflict with humans, as in the case of a well-known grizzly bear in Alberta in 2017.

Going Forward

This entire discussion can seem like a luxurious philosophical exercise at a time when we are witnessing massive worldwide declines in species and biodiversity. However, there is a long-term relevance to deconstructing and evaluating the use of anthropomorphism in conservation. Someone could reasonably say that given the current global conservation crisis, if anthropomorphism will get people to care, then we should do anything we can to mobilize support. Perhaps.

The problem with anthropomorphism is that it distorts the larger landscape context in which wildlife exists and the social-political realities in which conservation operates. Misrepresentations of nature can make it difficult to filter and evaluate conservation options based on the realities of wildlife and their ecosystems. Consider the popular images of lions and elephants in Africa. The social, family-oriented nature of these species is often highlighted in film and television. These stories make it difficult for the public to objectively evaluate the merits of hunting as a tool to generate revenue for the conservation of these species and the social considerations in their management. We also commonly see the use of value-laden language such as “slaughter” or “murder” to describe hunting, portraying wildlife as something other than wild.

I started this post with a great deal of cynicism about anthropomorphism. I have a ways to go before I’m convinced that it can be an effective long-term conservation strategy. Researchers who have promoted its use have pointed out that it is not a “miracle cure” and have suggested that we instead work to create a kind of “enlightened anthropomorphism” whereby messaging is accompanied by arguments in support of natural biodiversity and processes. I’m just not sure if people will read that kind of fine print. But perhaps my friend was correct that anthropomorphism can create a sense of fascination with wildlife and convince people that they should care. If we achieve that first and most fundamental step, then we at least open the possibility to shape the public’s ideas more positively and can work on creating long-term conservation behaviour.

Interesting article. I’m curious about your thoughts on the impact of anthropomorphism on the anti-hunting community, and their ability to influence the opinions of the non-hunting public.

I think that’s a whole other follow-up article! But really, knowing the predominant audience of this site, I took a few liberties with some assumptions with this piece. Most importantly, I took it somewhat for granted that most people on this site would appreciate the important connections between hunting and trapping and conservation (on many levels, including historical, political, social-cultural, and environmental). So when I talk about the impact of anthropomorphism on conservation, and particularly the ability of the public to evaluate and support potential conservation policies and actions, I’m including hunting, trapping, and angling under that umbrella of conservation.

I think your point is important though, that there is a more direct conversation about the impact of anthropomorphism on hunting by way of its use in anti-hunting campaigns. I allude to that in the article when I make reference to the deliberate uses of anthropomorphism. It is certainly one of the tools in the anti-hunting toolbox. By blurring the very real ecological differences between humans and wildlife, anti-hunting campaigns use anthropomorphism to confuse and encourage people to act on emotion rather than logic or science.

I’d be interested in hearing your thoughts too, Mark.