October News: No Winner Yet in Natural Fur vs Fake Fur Debate

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeThe debate over natural fur vs. fake rages on in the media, but with no new arguments being put on…

Read More

Truth About Fur – The Blog is an opinionated and free-wheeling new voice for the North American fur trade. This blog is a place for open discussions about the ecological, social and even philosophical dimensions of fur in our society. We will also address criticisms head-on, challenging some of the unfair misconceptions about our trade that some animal activists continue to propagate. All our guest bloggers are real people who make their living in the modern fur trade – as farmers and trappers, or in auctions, processing, design and fabrication or marketing. Please read, share and comment. We only ask that if you comment on the post, please do so with respect. We hope you enjoy Truth About Fur – The Blog. For more information about the North American fur trade, please visit our website, Truth About Fur. – Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About Fur

The debate over natural fur vs. fake rages on in the media, but with no new arguments being put on…

Read More

The debate over natural fur vs. fake rages on in the media, but with no new arguments being put on the table, it's hard to tell whether our industry is gaining ground. On the upside, the sustainability argument is now front and centre, and fake fur is taking a beating, as in a recent Huffington Post piece, "Faux fur is made of plastic, and it's not helping the environment." On the downside, almost all media reports are using the same cute but unhelpful hook: that both natural and fake fur are bad, so what are we to do? Here's a classic example, from Fashion United: "Fashion's battle with fur: real vs faux".

They call it "balanced reporting", but there are no winners when the message getting out is that neither natural fur nor fake fur is the way to go.

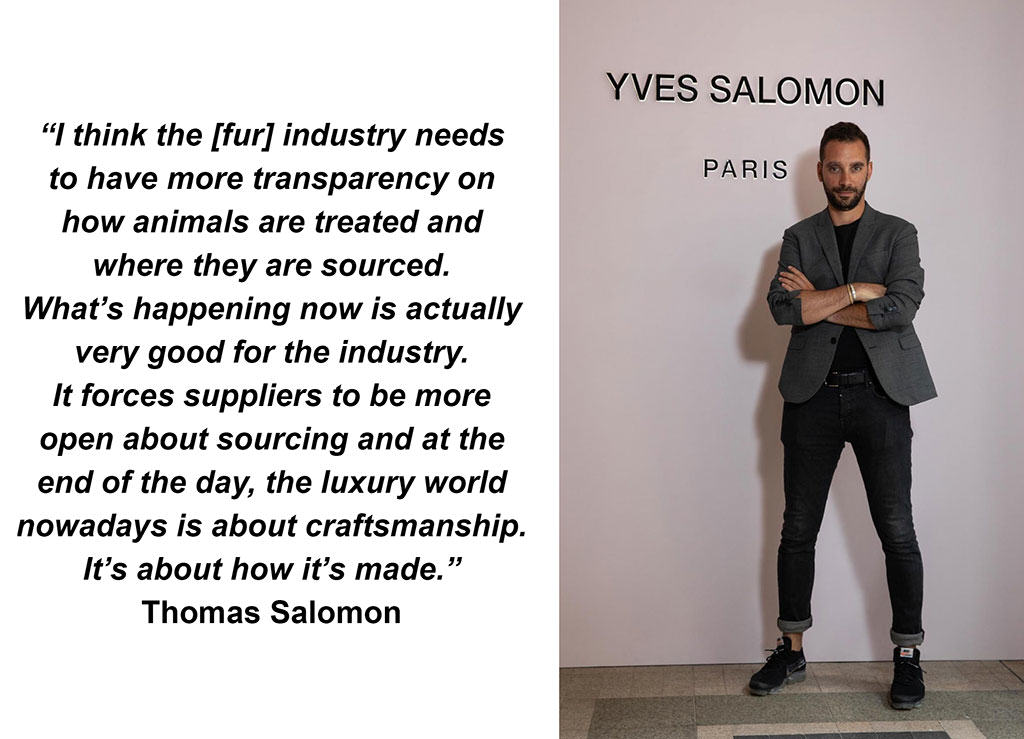

But heh, let's be optimists, like Thomas Salomon, fourth-generation owner of designer brand Yves Salomon. Thomas is a great spokesman for the fur trade as a whole, not just the retail sector, and he is adamant that the cloud now hanging over natural fur has a silver lining. When asked by Hong Kong Tatler whether fur was "a dying industry," he responded, "It’s not a dying industry, but rather it’s a time where it’s modernising itself."

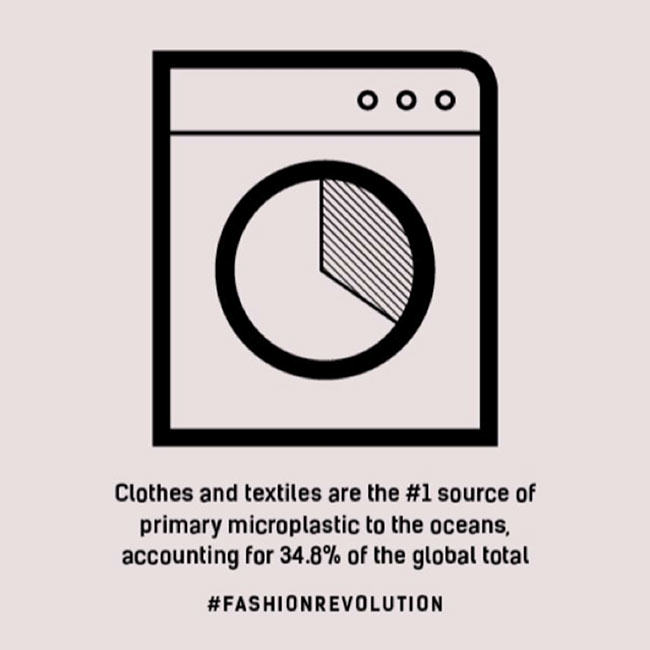

In other fur fashion news, the Korea Herald covered last month's Asia Remix, a contest for young designers working with fur, organised by the International Fur Federation. On hand to spread the word was Kelly Xu, CEO, IFF Asia Region. “Using fake fur damages the Earth, with the waste going to the oceans, affecting the entire ecosystem,” she said. “Fur is natural material which has been used by humans for thousands of years. It is biodegradable, it is sustainable fashion.”

Meanwhile, there's nothing better for a designer brand than some celebrity endorsement, and guess who reaped the windfall last month? When actress Katie Holmes stepped out in Manhattan, she was wearing a snuggly fox-trimmed coat from none other than Yves Salomon. Interestingly, celebrities are in far less of a rush to ditch fur than designer brands like Gucci.

Urban wildlife has been in the news again, and will be a regular fixture in the future. Even on the other side of the pond there's interest in North America's special problems, with the UK's Guardian featuring Toronto's raccoons. For some residents they are "scrappy heroes" but for others they are "villainous thugs". In case you missed it, "Conrad" the raccoon achieved fame posthumously when he died on a Toronto street in 2015. During the 12 hours it took for city services to pick him up, 'coon fans erected a memorial shrine to him.

Raccoons, of course, are a primary carrier of the rabies virus. A staggering statistic in "The value of modern day trapping" in The Bradford Era is $550 million - the cost of controlling rabies in the US annually. Without trapping, it is estimated this would balloon to $1.5 billion.

Urban coyotes are at it again, this time in Roswell, Georgia. Trapper Tim Smith was called in and soon trapped four. “They’re eating all the small dogs in the neighborhood, rabbits, every once in a while, we’ll get one that wants to come up to kids at the bus stop,” he said.

SEE ALSO: Will urban coyotes change the animal rights debate?

While North Americans argue about the place of trapping in wildlife management, New Zealanders understand. True, their eradication programs target invasive species, such as possums and rabbits, but animal rights opposition is almost unheard of. Here's an inspiring story of one man's efforts to protect a breeding colony of indigenous seabirds from rats, stoats, mice and hedgehogs. "Unfortunately, conservation in New Zealand is all about killing things,'' says conservationist Graeme Loh. "It is grim. I've been involved in the biodiversity part of things for many years, and most of my work has been working out better ways to kill more of the right stuffs at the right time.''

SEE ALSO: New Zealand designer embraces wild rabbit "eco-fur".

Education, of course, is the key, which is why the Timmins Fur Council in Ontario takes its outreach programs to kids and families very seriously. Read "Put down your gadgets kids, learn to love nature" by council member Kaileigh Russell. If the name sounds familiar, that's because the council was co-founded by her grandfather fully 50 years ago.

Last but by no means least (especially if you're a Brit yearning to live in the past), learn about a traditional form of wildlife management that's making a comeback: molecatching. "Moleskin: A unique fur once favoured by British high society" is a story of royalty, a pest, and a unique fur that takes 600 pelts to make one coat!

Two fur “bans” that aren’t fur bans grabbed the headlines in September. Even if there’s just a smell of a…

Read More

Two fur "bans" that aren't fur bans grabbed the headlines in September. Even if there's just a smell of a possible ban, animal rights advocates always trumpet it to the heavens because it increases pressure on policymakers to pass one if the media and public believe it's a fait accompli.

The Los Angeles city council voted to have legislation drafted that would ban fur retail and manufacturing. The proposal is facing stiff opposition, not just from the fur trade, but that didn't stop animal activists - and some of the media - from announcing a done deal. The Fur Information Council of America and the International Fur Federation are calling this "fake news".

Most of the media, thankfully, realised that a ban is a long way from actually passing into law, have been sceptical about its merits, and have given space to opposing views. "LA should scrap its ban on fur," wrote Will Coggin of the Center for Consumer Freedom in the Washington Examiner. "Pro-fur officials challenge L.A. city council’s vote on fur sales ban," reported Women's Wear Daily.

The National Post gave voice to Nancy Daigneault and Mark Oaten of the International Fur Federation, who wrote: “This is public policy based on lies, flawed studies and false allegations as those proposing the ban have not proactively reached out to the fur industry to learn about the high animal welfare and environmental standards in place. Nor have they learned about sustainability in a meaningful way."

Another fur "ban" which wasn't really a fur ban was at London Fashion Week. The British Fashion Council, which organises the event, opted to play a risky game by announcing that no fur would be shown at this year's event. Of course, animal rights groups and much of the media announced this as a ban (see, for example, this article by Fashion Network), but the Fashion Council insisted there was no ban. It was simply a case of no designers choosing to show fur. So why did they even bother to announce it? Presumably in the hope animal rights activists would stay away.

Meanwhile, animal rights groups continue to pressure designer brands to drop fur. The latest to fold is Burberry, and now the heat is being ramped up on Prada. Note again how activists and the media always refer to these as "bans" when they're nothing of the sort. Burberry (or whoever) has not "banned" fur; it's merely decided to stop using it for now. And almost all of these brands will continue using shearling (sheep fur), not to mention python, crocodile, and other exotic leathers.

As for how the trade will ride out this trend of fur bans (real or imagined), Truth About Fur's blog asks: "After the siege: What is the future of fur?"

Meanwhile, we all know how important social media are to animal activists, so here's an in-depth look at how they're used against the fur trade: "How social media is pushing fur out of fashion".

Last month, the International Fur Federation launched two fashion campaigns, the Natural Wonder campaign and the Fur Now campaign, to highlight the importance of responsible fashion, informed consumer choice, and the sustainability of fur.

Also, Women's Wear Daily ran a feature entitled "Fur: A sustainable, versatile choice" on Chunchen Liu, winner of the REMIX 2018 competition organised by the IFF with the support of Vogue Talents. (Download the whole issue in PDF here.) Having now produced a collection with Saga Furs, Chunchen is already proving herself an informed advocate for fur. "Fur has strong sustainable credentials," she told WWD. "Unlike comparable petroleum-based synthetics made of plastic, natural fur is a completely biodegradable material, which does not further burden nature. Every stage of fur production is sustainable. ..: Also, natural fur lasts for decades if professionally cared for, unlike chemical-based fur that ends up in landfill sites often after a single season. Fur can also be passed down through generations and remodeled and restyled in a variety of ways to keep it modern." We couldn't have said it better ourselves!

Animal rights activists will pick on anyone, large or small, but they're never scarier than when they're going after small businesses.

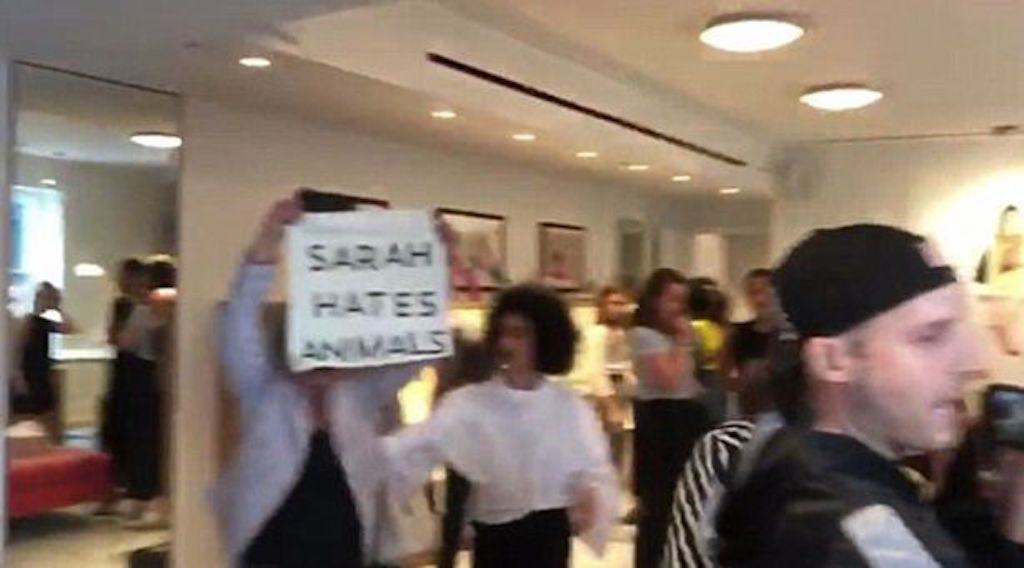

Actress and fur lover Sarah Jessica Parker had hoped for a fun event to mark the opening of her new store in Manhattan, but instead the store was invaded by animal rights bullies chanting, "Fur trade, death trade." Fifty years ago, security would have thrown them headlong out the door, but if you do that today, their lawyers will be all over you.

Someone who can surely relate is Faye Rogers who opened a fur store in England and closed it in September after just four weeks. Business was good and then the protestors turned up, and 1,000 hate messages and threats arrived in four days from around the world. Said Rogers, "These trolls are hiding behind a mask of being vegan and animal-loving just so they can be nasty. They are bored and have nothing to do with their lives."

Meanwhile PETA has decided it wants to close down a New Brunswick company that processes lobster and crab shells into powder that is used in the bio-medical industry and as fertiliser. It sounds like a tremendous sustainable-use initiative, but of course PETA doesn't want us eating lobsters and crabs in the first place. And why not? "Lobsters are intelligent, sensitive people who do not want to be killed," according to a spokeswoman. You read that right, lobsters are "people"!

It's great to see that the company largely responsible for propelling coyote pelt prices to record levels is expanding its production. Canada Goose is about more than just coyote-trimmed, down-filled parkas, of course, but we should celebrate that a strong advocate both of fur and sustainable use is doing well. The new manufacturing facility, in Winnipeg, will be its seventh and largest, and create 700 new jobs.

Sadly, last month saw the passing of the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin. She was far too talented and independent…

Read More

Sadly, last month saw the passing of the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin. She was far too talented and independent an artist for anyone to ever claim her as their own, but there's no denying she wore fur with style. In later life, her stage performances incorporated a signature move of dropping her full-length mink or chinchilla on the floor to signify she was shifting into high gear. Rest in peace.

It's always great to see members of the fur trade using the media to spread our messages.

If you're happy with publicity and have something to say, make yourself available for interviews, like fourth-generation furrier Thomas Salomon who was recently featured in the South China Morning Post. In "Why furrier Yves Salomon dismisses the anti-fur movement that is sweeping fashion", Thomas pulls no punches. "What’s happening right now is just a fashion cycle," he says. "In fact, I call it the hypocrite cycle. It's easy for brands to cut [fur] out when it makes up less than 0.1 per cent of their turnover. Plus half the time these brands don’t have a consistent strategy.”

Another great way to get heard is to submit an op-ed piece, but they're a mixed blessing. With minimal editorial control by the media organisation, op-ed writers can speak freely to the point that they often just end up regurgitating propaganda. So it was a relief when Business of Fashion, after publishing an anti-fur tirade from an animal rights group, gave equal space to International Fur Federation CEO Mark Oaten and Vice-President Americas Nancy Daigneault, in "Fur: A reality check".

Easiest of all is writing letters to the editor, like this impassioned plea from a resident of New Hampshire, "Trapping, like hunting, is a conservation tool".

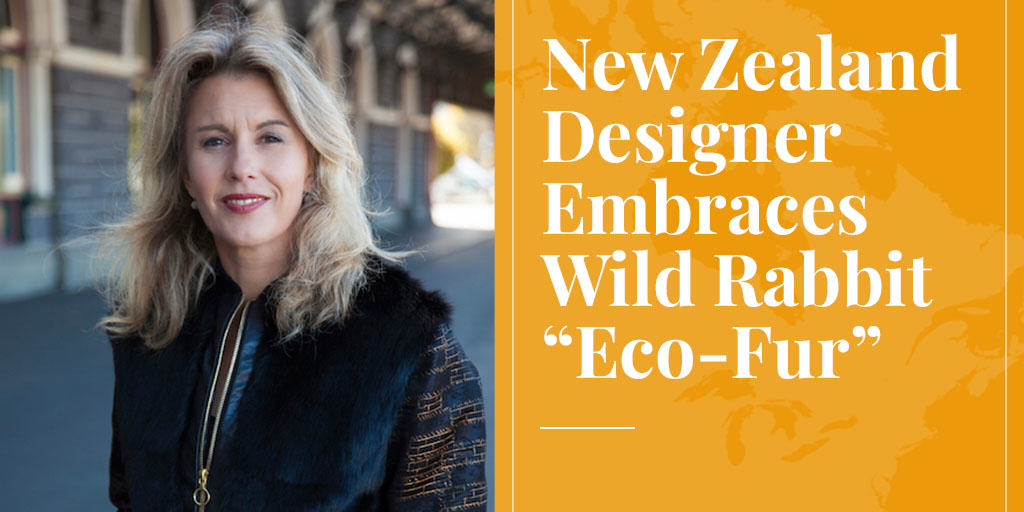

Rabbit fur is far more common than you might think, but it almost never makes its way into the collections of luxury brands. Now Jane Avery, from Dunedin, New Zealand, is bucking the trend with her stunning range of garments combining exotic fabrics with wild rabbit. And she's helping protect the environment at the same time, since rabbits are a real pest in her part of the world. Check out our interview: "New Zealand designer embraces wild rabbit 'Eco-Fur'".

Rabbit farming is alive and well too, in Aitkin County, Minnesota. The Nord Lake Rabbitry used to be a mink farm, but now raises rabbits for food and fur, rotating them with crops that benefit from the "phenomenal fertility" of rabbit manure.

Fox chaser: A winter on the trapline is a new documentary film from the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. that follows a young Cree trapper's way of life in the northern Alberta wilderness. CBC's story and the official trailer are here, and if you're lucky enough to live in Canada, you can watch the full documentary here.

Much closer to home, Truth About Fur's Alan Herscovici reports on his experience "Spring muskrat trapping in Quebec" with Pierre Canac-Marquis, coordinator of the Fur Institute of Canada’s humane trap research and development program. “It’s a passion,” says Pierre. “It’s certainly not for the money; I’ll be lucky to get four dollars a pelt for these rats. But the farmers are happy we’re here, because muskrats undermine the stream banks with their burrows. That speeds erosion and they lose large strips of farm land along the drainage ditches."

Here are a couple of cautionary tales about what can happen when wildlife are left to their own devices for too long, with no management plan. Nutria are notorious for damaging wetlands, and there are so many on the US west coast now that they pose "a threat to California's environment similar to a wildfire or an earthquake." Meanwhile, Argentina and Chile are hoping to remove 100,000 beavers - originally introduced for their fur - because the North American natives have clear-cut the old-growth forest in Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia.

The bandwagon of fur-ban stories keeps right on rolling, with two Californian cities front and centre. San Francisco's ban on fur sales, set to come into force next year, prompted the writing of "San Francisco bans everything", a tongue-in-cheek piece that would be funny except it's also true!

Meanwhile in Los Angeles, the city council is being asked to consider a fur ban of its own. This prompted another piece about the seemingly endless string of bans in California, "The fur flies in L.A. as city considers ban". If you want to send a message to the council explaining why a ban would be a bad move, ShoppersRights.org makes it incredibly easy.

Feel free to refer the LA council (or anyone else considering a ban) to our new blog post, "Proposals to ban fur sales are anti-ecological".

Sightings of "urban coyotes" continue to rise in North American cities, while Montreal launched a hunt for one coyote believed to have attacked three children.

SEE ALSO: Will urban coyotes change the animal rights debate?

According to a survey commissioned by the Montreal SPCA, 72% of Quebecers expect their legislators "to adopt legislative measures and policies designed to ensure the welfare of the province’s animals.” That sounds fine, since the fur trade supports animal welfare too. But if you're looking to start writing letters to the editor, look out for headlines like this one from the Canadian Press: "Study: 70 per cent of Quebecers feel animal rights are an important election issue." Animal rights and animal welfare are not the same - a message we just need to keep repeating.

SEE ALSO: Animal welfare vs. animal rights: An important distinction.

In the battle to win fake-fur fans over to natural fur, we could have a new piece of ammo. Apparently the most widely used plastic, polyethylene, emits methane and ethylene as it breaks down, and both of these are greenhouse gases. We did not know that, and will be following closely!

Responsible fashion, informed consumer choice, and the sustainability of fur are front-and-centre in two new fashion campaigns for Fall/Winter 2018-2019…

Read More

Responsible fashion, informed consumer choice, and the sustainability of fur are front-and-centre in two new fashion campaigns for Fall/Winter 2018-2019 from the International Fur Federation. In preparation for the global launch on September 3, TruthAboutFur’s senior researcher Alan Herscovici spoke with the IFF’s director of fashion, Jean-Pierre Rouphael, about these exciting new campaigns.

TaF: The IFF’s new consumer campaigns take a very innovative approach, combining beautiful fashion photography with a strong environmental sustainability message. Can you tell us about this?

Jean-Pierre Rouphael: At the IFF’s annual meeting last Fall, in Barcelona, the board decided it was time to promote the modern fur trade’s unique sustainability credentials. The anti-plastic movement was dominating mainstream media and people were talking about the environmental damage caused by plastic – which of course includes fake fur. It was the perfect opportunity to emphasize our "natural" story – the sustainability of fur.

SEE ALSO: Fur is a sustainable natural resource.

Young people, especially, are increasingly concerned about how our lifestyles and consumer choices will affect the planet, so the timing is good. The challenge was how to tell this story in a fashion context. The solution we found is a two-pronged approach. One is a beautiful fashion campaign in Vogue magazine that incorporates our environmental message in the text. We call this campaign "Natural Wonder". And then we have a new digital campaign, called “Fur Now”, which centres on creative young people explaining in their own words why they love working with fur, and part of the conversation is about fur's sustainability.

TaF: Let's talk about the "Natural Wonder" campaign in Vogue first.

J-P Rouphael: "Natural Wonder" is a three-month exclusive campaign in Vogue, in six major markets – Spain, Italy, Germany, France, Russia and the USA – plus limited usage in China and Korea.

This campaign has been launched in Vogue's September issue, and will be followed by ads in the October and November issues, as well as on Vogue’s digital and social media platforms. The photography shows new fur creations by top designer brands, including Roberto Cavalli, Carolina Herrera, Oscar de la Renta, Fendi and others.

TaF: We notice that the fabulous photography is shot outdoors, not in a studio.

J-P Rouphael: Yes, the shoot was produced by the Vogue team, and we chose Dario Catellani to do our photography because he loves working outdoors, with landscapes and natural light. We felt that was important to reflect our message that fur is a natural product and a responsible choice.

TaF: And the message is clear, right from the bold headline: “Natural Wonder – Sustainable and beautiful, ethical and exquisite, the magic of fur is irresistible.”

J-P Rouphael: Yes, and the text that follows is also very direct. We explain that growing concerns about pollution caused by the production and disposal of plastics – like fake furs and other petroleum-based synthetics – make long-wearing and biodegradable natural materials, like fur, a better choice than ever. As we say in the text, “A fur coat is the ultimate refutation of the buy-it-and-toss-it ethos of environmentally destructive fast-fashion.”

TaF: Now tell us about your second campaign, "Fur Now".

J-P Rouphael: The Vogue ads will be supported and complemented by a brand new "Fur Now" campaign that we are especially excited about this year. We have created eight fast-paced video stories featuring creative young people who are actively involved in the fashion industry. We will be featuring one of these video profiles each month, from September through December, and another four from February through May. But you can see all eight of these wonderful young creators on the IFF website now or right here on TruthAboutFur (see below).

TaF: It’s a very modern and engaging approach.

J-P Rouphael: Yes it is. These are real people and they express themselves in their own words. We intentionally did not script them; we just turned on the cameras and asked why they love working with fur, and that’s why the videos are so wonderfully sincere and authentic.

TaF: You have chosen young designers, artisans, and businesspeople working in different markets, in Europe, Asia and North America.

J-P Rouphael: Yes, some are new to the industry, and some are bringing new energy and ideas to multi-generational family businesses, like the charming 21-year-old Romanian woman whose grandmother started their store in Bucharest. There is also a British fashion blogger, someone who doesn’t work in the fur industry, but is nonetheless very interested in the environmental advantages of using natural materials like fur. These are authentic young voices that clearly demonstrate the dynamic creativity of our industry. And the fast-paced editing is also designed to speak directly to Millennials and Generation Z.

TaF: How will these "Fur Now" video stories be promoted?

J-P Rouphael: The campaign will be launched on Elle.com and HarpersBazaar.com through September and October. We will also have more than 40 print insertions in Elle, Harper’s, Cosmopolitan, and Grazia in the EU. There will also be a mailer to the Elle and Harper’s subscription lists. In all, this campaign will reach more than 100 million target consumers, compared to about 86 million reached by last year’s campaign.

TaF: An exciting campaign, indeed! Before we go, tell us a bit about yourself and what these campaigns mean for you personally.

J-P Rouphael: I have worked in fashion communications for the past 14 years, mostly with luxury fashion. I was born in Lebanon and worked for much of my career in Dubai, with clients including Valentino and Ralph Lauren. I moved to London a few years ago, and I am especially happy to be working with the IFF because I love fashion and fashion marketing.

Although I am experienced in promoting luxury, working on last year's "Fur Now" campaign was brand new to me. But touching and feeling fur, shooting it, and seeing how it uplifts any outfit and look, it became organic and easy for me to advocate and sell it through imagery and communication as a timeless beauty while still a modern-day luxury.

And, of course, we have an important story to tell about fur being the responsible choice for our eco-conscious times, especially as we become more aware of the environmental problems associated with fake fur. We believe that we have an extraordinary opportunity now to spread this very positive message about fur. That's why the slogan appearing on all our communications is: “Natural Fur – The Responsible Choice”.

We’re used to hearing polarised arguments about fur, either strongly in favour or strongly against. But many people hold views…

Read More

We’re used to hearing polarised arguments about fur, either strongly in favour or strongly against. But many people hold views that fall somewhere in between. One such person is fashion designer Jane Avery, from Dunedin, New Zealand, who is garnering attention for her work with just one type of fur, wild rabbit, under the brand name Lapin (French for rabbit). So is she pro-fur or something quite different? Let’s find out …

Truth About Fur: According to Lapin’s website, you specialize in “limited edition, bespoke and one-of-a-kind garments.” Can you describe some of your garments?

Jane Avery: The coats and jackets I have made to date are a combination of New Zealand wild rabbit fur and beautiful top-quality fabrics. When I started out with this concept three years ago I used appropriate fabrics to hand in my stash. I also had the opportunity to travel to India where I sourced heavy silk vintage saris and traditional embroidered woollen textiles. What resulted was a collection of one-of-a-kind creations. I also make limited-edition, made-to-measure bespoke pieces incorporating new fabrics such as 100% wools.

I live in a cold part of New Zealand and creating coats with exceptional warmth yet still retaining elegance and indulgence in gorgeous textiles is my aim. My original concept was to make garments using rabbit fur panels for yokes, collars, cuffs and upper shoulders. The furrier I work with prepares these for me. The fabric sections are insulated with a 50% cotton 50% wool batting so they can match the warmth given by the fur. The same goes for the insulated sleeves of Lapin bomber jackets which have rabbit fur bodices trimmed with leather.

TaF: Tell us about the production process. How many hours go into each garment and do your prices reflect this?

Jane Avery: There is a lot of hand preparation before the sewing machine gets involved. Because fur isn’t sewn with seams like fabric is, I turn in and hand-baste the seam allowances on the fabrics in order to create clean, secure edges to attach to the fur. It’s an example of slow fashion in action and it’s certainly not high tech. Some coats can take up to 50 hours to make.

It’s been an intense development process (I am essentially a self-taught sewer of over 20 years) and I’m quite the perfectionist. There’s extensive handwork tailoring and securing the inside of the garment before the coat lining is bagged out and the inner sleeve is hand-sewn shut. What results is a highly finished garment that’s as close to perfect as I can make it.

Of course this attention to detail and made-to-measure process is reflected in the eventual price of the garment. Also the quality of the textiles and the fact that the fur passes through the hands of my rabbiter, tanner and furrier before it gets to me puts Lapin pieces in a higher price bracket.

SEE ALSO: I'm an artisan designer: Fur and leather keep me warm.

TaF: Who are your clients?

Jane Avery: My clients to date have been people who recognise the skill and dedication in crafting a Lapin piece and want to invest in something special that, well cared for, will take them through many years of pleasurable wearing. It’s my hope that Lapin pieces will become heirlooms handed between generations. For the vintage fabrics I’ve been repurposing, such as the saris and woollen paisleys, this has particular resonance. I adore the concept of well-preserved, pre-loved antique fabrics being given new purpose and continuing their usefulness and beauty in companionship with New Zealand Wild Rabbit Eco-Fur.

TaF: Historically, before the expansion of fur farming made mink and fox more affordable, rabbit was called “the great imitator” because it could be treated to resemble mink, ermine, fox, beaver, and even seal. Do you take advantage of this versatility and how?

Jane Avery: The way I came to using rabbit was not because I wanted to imitate or emulate furs from other countries, but because I saw a New Zealand pest-resource that wasn’t being used to its potential. Of course I’m very open to experimenting and learning how I can manipulate this wild resource in a fashion sense. I do dye a proportion of the skins I use jet black, and I’m looking forward to being able to afford dying in other colours. For the integrity of the Lapin brand and message, which is to promote the use of this specific pest resource, I feel it is important for it to retain its own special identity.

TaF: The Lapin website says you use “responsibly sourced New Zealand ‘Wild Rabbit Eco-Fur’.” What do you mean by “responsibly sourced” and “Eco-Fur”?

Jane Avery: Lapin rabbit furs are harvested from the eradication catch of New Zealand high-country rabbiters. The responsibility these workers have, employed by high-country station owners, is to control the rabbit populations. If the rabbits are left unchecked, they reach plague proportions. Historically and to this day they destroy thousands of acres of grazing land and also the delicate native vegetation characteristic of the New Zealand sub-alpine landscape, such as tussock grass. They cannot be allowed to stay. This is an imperative of the New Zealand high-country environment.

The rabbits for Lapin generally die from a sharp shot to the head and are sourced at nighttime when their eyes can be seen shining in the beam of the rabbiter’s spotlight. To my mind this is as close to an instantaneous death with as little suffering as possible. It is responsible in that it deals with the problem skilfully and with respect to causing the animal the least suffering.

Lapin fur can be considered an "Eco-Fur" because by wearing it you contribute to restoring the natural New Zealand environment. It is a pest resource which means the rabbits are not being purposely bred for their fur. My creative philosophy for Lapin is to use as much as I can of what I have available around me. The rabbits are here and must be dealt with. Yes, there is tragedy in the deaths of these sentient beings, but I believe my view is one of practicality and realism. Wearing the fur of these animals can be considered a "woke" alternative to indulging in other furs, be they farmed or faux.

SEE ALSO: Is it ethical to produce, buy or wear fur?

TaF: Most rabbit fur today comes from young animals bred for food, but the best pelts are said to come from adult wild rabbits that are taken in winter, when the fur is thick and even. Are you selective about the pelts you use?

Jane Avery: I am selective about the pelts I use. As a wild catch, it is variable in quality. I’m fortunate to work with a rabbiter who will grade the best pelts for me in the course of his work. The season here in New Zealand for optimum skins runs in winter from July to October when the chilly southerly winds are blowing into the New Zealand South Island high country. This means the rabbits have their winter coats on and are not moulting.

I like to use thick, fluffy furs with firm yet pliable skins suitable for construction in bomber jackets and structured coats. I also love the way many of the young doe rabbit furs are so sleek, smooth and floppy. These are great for scarves, capes and more unstructured styles. I am still experimenting with what is possible and learning so much every time I get a new batch of furs to work and create with.

TaF: Rabbit fur has a reputation for shedding easily, causing uneven patches in the fur. Is this reputation deserved, and are there ways to minimise shedding?

Jane Avery: The way to minimise shedding is to harvest during the winter when the animals are holding onto their fur for warmth. When I started out, I tested furs by continually rubbing and shaking them. My view is if you get them at the right time of year the shedding is tolerable.

Rabbit fur is what it is. It’s a natural resource and even with its reputation for shedding is a beautiful, practical material worthy of inclusion in high-end garments. Looked after well, it will look good and retain its warmth-giving properties for many, many years. It’s important to look after it properly such as being aware of not continually slinging leather bag straps on your shoulder or rubbing with car seatbelts. At least when it sheds you know the little bits are safely bio-degrading in the environment and not polluting the planet like the microfibres shed from synthetic “furs”.

TaF: Possums are also considered a pest in New Zealand. Is possum fur something you’d consider using?

Jane Avery: Lapin was founded on the notion of creating attention for the very under-utilised pest-resource of New Zealand wild rabbit. However it is just a name and I’m certainly not closed to using New Zealand possum fur as my business grows. From an aesthetic point of view, I like possum fur when it has been shorn down to a nice soft pile. As with rabbit fur, the creative possibilities with this pest, notorious for destroying our native forest habitats, are many.

TaF: Another source of fur which has a small but growing following is vintage furs which are remodeled and recycled. Is this something you would consider doing?

Jane Avery: I like the idea of repurposing vintage furs, and yes, it’s something I’m open to working with as my business develops. From my own wardrobe I wear a vintage chinchilla-rabbit coat which I found in a Salvation Army op-shop. It sheds like you wouldn’t believe so I’m banned from sitting in my son’s plush car seats when I have it on!

SEE ALSO: 5 great ways to recycle old fur clothing.

TaF: How do you feel about using farmed fur, such as mink or fox? An argument in favour of using farmed fur is that it takes pressure off wildlife populations, and in fact most of the demand for fur these days is met with farmed fur.

Jane Avery: Personally I would not use farmed fur for Lapin. It would be contradictory to Lapin’s essential message and philosophy.

I feel I am well enough informed about the whys and wherefores of fur farming and I understand the animal welfare standards are generally high, and in many cases higher than other industries exploiting animals for their meat and skin. As a sewer I also respect the tradition and craftsmanship of the fur industry. But farmed fur is not something that I would purposely seek out as a product to work with.

I find reassurance in the fact that New Zealand wild rabbits, an introduced species, are essentially having a marvellous time living natural, free lives, eating and breeding in the great outdoors. At least when they meet their deaths at the hands of a rabbiter they are free, albeit in the wrong place in the world. If they were not an ecological problem in this country, I would not be exploiting their fur for fashion, nor would I seek out other furs … aside perhaps for possum.

TaF: North America has its own problems with invasive nutria as well as indigenous furbearers that cause problems if their populations are not managed. For example, muskrats destroy marsh habitats, beavers cause flooding, and coyotes prey on livestock and are expanding into urban areas where they prey on pets and bite children. Are you supportive of using these species for their fur, provided it is done sustainably?

Jane Avery: To me it’s all about context. The world we live in is so very different to the world of 150-200 years ago. Sure, North America has its problems with invasive species too, and certain situations demand certain responses. If it’s deemed these animals must be "sustainably" culled then it would be disrespectful not to make practical use of their fur.

With the New Zealand rabbits, the context is created by human history. The tragedy is that they were introduced to this country in the first place.

I believe anyone in the business of exploiting animals for what they can provide to humans should check their moral compass on a regular basis. We shouldn’t necessarily do things just because that’s the way we’ve always done them. Everything must be considered within its realistic context and with the good of the environment central to decision-making.

***

SEE ALSO: Inside a rabbit fur fashion designer's 10 sqm solar-powered eco cabin in Central Otago. This NZ Life.

Our July news roundup focuses on two areas where a little more common sense could solve everyone’s problems. When wild…

Read More

Our July news roundup focuses on two areas where a little more common sense could solve everyone's problems. When wild furbearer populations grow too large, whether they're invasive or indigenous, common sense suggests we cull them and make use of the fur and meat (if they're tasty). But animal advocates want us to share space even with dangerous wildlife while calling for fur bans.

The Darwin Award for managing invasive wildlife goes to Canmore, Alberta, where a program is under way to control an explosion of rabbits. It's not that the locals don't like rabbits, but some don't like all the hungry cougars, coyotes and bears they're attracting. So far, 1,300 rabbits have been trapped and euthanised, with most going as feed to a wildlife rehab centre. But now everyone's upset: rabbit lovers, obviously, but also taxpayers who are paying $300 per rabbit caught! Plus the program's not working because the rabbits are breeding like, well, rabbits. Duh!

A fashion designer in New Zealand, where invasive rabbits cause extensive environmental harm, has a much better idea. Jane Avery is turning rabbits into fur coats under the label Lapin (French for rabbit). "If you wish for the luxury of fur, then maybe you should be making an eco-conscious choice,” says Avery, who is not so much a fur fan as a lover of her natural environment.

Don't expect rabbits to vanish from Alberta or New Zealand any time soon, but efforts to eradicate invasive species do occasionally succeed. One such case is the American mink in Scotland's Outer Hebrides. Decades after mink were released from fur farms, wildlife conservationists now believe they finally have them under control.

Indigenous wildlife can also present problems, like "urban coyotes". In a classic case of "you can't please everyone", traps were first installed in a park in Cambridge, Ontario, and have now been removed following a campaign against the "cruel" traps by Coyote Watch Canada. Said one confused resident who's afraid of the coyotes, "The city has to do something about it, but not hurting them as well because they have the right to live."

SEE ALSO: Will urban coyotes change the animal rights debate?

Beavers are also expanding their territory, onto the Alaskan tundra. “You just need to look at the map to see how well beavers recolonized the rest of North America after over-trapping," says an expert. "They are now in all the lower 48 states, and Alaska is the last standing – and it’s going to fall.” Given the radical changes beavers can bring to a landscape, the jury is still out on whether this is a good or a bad thing.

SEE ALSO: Abundant furbearers: An environmental success story.

Regardless of how some furbearers are expanding their range, calls for fur bans are also spreading.

In the UK, a Parliamentary debate in June considered the possibility of banning fur imports post-Brexit. The government said no, but the anti-fur lobby have kept up a steady flow of stories to the hungry media. Grabbing headlines in July was the spurious argument that fur should be banned because a few retailers have been caught labelling it as fake. The government has rightly said this is not grounds for a ban, but it seems to be wavering, as this BBC report shows.

Also in Europe, Ireland's Green Party will be reviving its bid to have fur farming banned there. This almost happened back in 2009, but got derailed during a period of political turmoil.

Back on this side of the pond, a ban on fur sales is approaching in San Francisco, and the fur industry has threatened legal action if it goes ahead. Animal rights leaders have also announced that New York City is in their cross hairs.

Last month Truth About Fur interviewed Katie Ball from Thunder Bay, Ontario. Katie says fur is in her blood and it shows! When she's not on the trapline, she's running her own fur fashion company or advocating on behalf of several outdoors associations.

We also ran an overview of the latest annual general meeting of the Fur Institute of Canada. For those not already in the know, the FIC is the country’s leader on humane trap research and furbearer conservation, and is the official trap-testing agency for the federal and provincial/territorial governments.

Let's close with some news in brief ...

In 2018, the International Fur Federation and Fur Europe commissioned a study comparing degradation of real and fake fur in a simulated landfill. Now they've released a video summarising the findings.

SEE ALSO: The Great Fur Burial.

In sealing news, a reopened tannery for sealskin in Alaska is having trouble keeping up with demand (pictured above), while on one of the remote Pribilof Islands the annual fur seal hunt was allowed to start three days early because groceries were running out.

Farmed mink production in the US fell slightly in 2017, but the total value of the harvest was up thanks to higher prices. Read the official US Department of Agriculture report and an analysis by Capital Press.

This year's winners of the Yukon Innovation Prize say they want to turn the fur industry upside down. Team Yukon Fur Real plans to buy pelts from local trappers and help artisans create fur products that can be sold to consumers.

Calling sports fans, a fur coat owned and signed by Joe Namath is up for auction! To place your bid, click here. As of August 1, there are zero bids, perhaps because the reserve price is $10,000!

Katie Ball is a trapper from Thunder Bay, Ontario who also runs her own company, Silver Cedar Studio, designing and making…

Read More

Katie Ball is a trapper from Thunder Bay, Ontario who also runs her own company, Silver Cedar Studio, designing and making fur garments. She is a strong advocate for fur, representing the Northwestern Fur Trappers Association, the Ontario Fur Managers Federation, the Northwestern Ontario Sportsmen’s Alliance, and Fur Harvesters Auction. Let's find out more about the woman who says fur is in her blood ...

Truth About Fur: You grew up helping your father run a trapline, but spread your wings to work in pet sales, veterinary care, and as a fashion model. Yet you returned to trapping and in 2014 went into business producing fur garments. In an interview with the International Fur Federation, you said fur “is in my blood and who I am to the core.” How did that happen, and how does it feel to be so sure of who you are?

Katie Ball: It started as one simple question. I was at a trappers' convention looking over new techniques of fur-processing when my dear friend (and now mentor) Becky Monk reached over a sheared and dyed peach beaver pelt and asked me, "Have you ever considered working with fur?" I had been looking for a medium that would allow me to combine my love of nature, fashion modeling and creativity into one package. Fur was that medium.

Fur goes beyond my individual self. It encompasses our rich Canadian history, it is the warmest, most natural product on the market, and its uses and ability to be manipulated into so many versatile looks know no bounds.

For me to be a part of this tradition is humbling. I take pride in my upbringing in a trapping family, and will do whatever it takes to help pass that on to future generations.

SEE ALSO: The country that fur built: Canada's fur trade history.

TAF: You've been working the same trapline with your father since 1989. Tell us about it, and the changes you've seen.

Katie Ball: Our trapline is 150 km north of Thunder Bay. The terrain is enveloped by boreal forest and offers a variety of landscapes that allows for a broad range of furbearers to be harvested. Lakes, rivers, bogs, marshes, swamps, red and jack pine forests, birch and aspen as far as you can see over rolling landscapes, we have it all. From the warm start of fall to the frigid deep freeze of winter, we truly experience the four seasons nature has to offer.

Many changes have come to the landscape over the years – forest fires, logging, mining, roads and aggregates. But these are not as negative as many think. Old growth does not really exist in boreal forest; fires, pests and disease make certain of this. We have had two forest fires that I have witnessed. With burns come new jack pines that would not seed without the searing heat of the fires. New shoots and growth give food to the fauna. Logging can create better habitat for specific wild game, increasing numbers. Mining reclamation restores the surface to its original glory. Out of destruction some of the most amazing opportunities can arise, and Nature sure knows how to make the best of it.

On another level, I've seen animal populations rise and fall in synch with one another, like lynx and rabbit. Rabbits have approximately a seven-year cycle. As the population begins to increase so do the lynx. But then the rabbit population crashes, and the lynx decline right after. Moose populations sank with the cancelation of the spring bear hunt years ago, but the hunt has been reintroduced in hopes it can help the moose population recover.

TAF: You currently represent three outdoors associations, so you are clearly motivated to serve. What benefits do such organisations provide to the fur trade, and what would you say to a trapper who is undecided about whether to participate?

Katie Ball: These groups help give a voice to the outdoors community. Without them, we would not have a say on topics that could wipe out our passion, heritage and future. Most trappers just want to be out in the woods being stewards of the land, and I know the feeling. But politics wait for no man. We need to be on top of new regulations, legislation and activist groups who wish to do away with our lifestyle.

So get involved with your outdoors groups and make your voice heard. Help secure the future for our children, and take pride in what you do and love. We all share the same resource and our love of nature. There is strength in numbers, so why not work together to ensure that our way of life can be enjoyed for generations to come?

TAF: You call trappers “stewards of the land”. Can you give examples of how this works?

Katie Ball: Statistics show that there are more furbearers now than there were when the fur trade started. Populations are healthier, and even gene pools have benefited from trapping.

SEE ALSO: Abundant furbearers: An environmental success story.

Trappers notice the small things, like what animals are moving through an area and when, or changes in their food supply. Are certain berries and plants growing? If it's a wet and cold spring, we know that many of the grouse young will not survive, and this can affect predator populations.

By knowing the lay of the land and how it all interlinks, trappers are a vast wealth of knowledge. Logging companies looking for gravel or decommissioned roads are better off talking to the local trapper than just following their GPS. They may be told of a washout or an old trail that will save time, money and resources.

Wilderness groups collecting data are better off talking to a trapper who will have insight on the local flora and fauna, and maybe even historical data.

Outdoors enthusiasts looking for a great camping spot or trails to hike – a trapper can point them in the right direction.

Plus, if something were to happen, it’s nice to know that someone is always out there in case of emergency.

TAF: How do you respond to accusations by animal rightists that trapping is inherently cruel? And do trappers need to work harder, or differently, to have their side of the story heard?

Katie Ball: With all the work conducted by the Fur Institute of Canada and many other groups, and with the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards (AIHTS) in force, it is hard to believe that even with the highest standard of trapping regulations and certified traps that many still think of trapping as cruel.

SEE ALSO: Fur Institute of Canada champions humane and sustainable fur production.

I have found that by talking to the public, educating individuals on our regulations, and standing behind our ethical practices, most get a bigger picture and realize that we are not out to destroy animal populations with archaic trapping methods. We are out helping maintain a healthy balance in nature.

Trappers need to stand up to such negative rhetoric. We need to be heard, as silence accomplishes nothing. And it is so much easier to reach the masses today.

Many trappers are not interested in getting in front of a crowd or being filmed, but they can still make a difference with one person at a time. Take the time to answer questions from inquiring minds. Take someone out for a day that would normally never get the chance to experience the wilderness. Spark a passion in an individual that will last them a lifetime.

It is only by educating the public that we can stamp out the negativity that surrounds trapping.

TAF: You have experience both as a trapper and in the fashion world, and are now producing fur garments. The Silver Cedar Studio website says that being a trapper helps you understand fur “in the way a carpenter understands wood.” Can you expand on this?

Katie Ball: As a trapper I understand how the animals that I harvest live. I know their habitats and what challenges that may bring. And I understand the precautions and prepping that a trapper must undertake for each animal. That being said, as a designer, I can see fashion trends, take creative risks and develop a product specifically tailored for the individual customer.

By seeing both sides of this story, I am able to determine what furs are best suited for each and every fashion expectation and need of the customer. For example, warmth and durability are of the utmost importance to an outdoors enthusiast. Beaver and otter offer water-resistance, thick leather for durability, and dense underfur for holding air against the body while swimming. This translates to extra warmth for my client even on the harshest of winter nights.

TAF: On the subject of women as trappers, you told the International Fur Federation: “Regardless of gender, when it comes to working on the trapline, it comes down to individual strengths and weaknesses. There is no skill out in the bush that is labelled as gender specific.” Do women need encouragement to break the stereotype that trapping is for men?

Katie Ball: This is a question where the outside world perceives it differently than it is, and I do not understand why. When the world looks at trapping, it is visualized as almost exclusive to men. However the story is very different if you are part of the trapping community, or even just visit a trappers' convention.

To quote my friend and freelance writer (who is not a trapper) Ava Francesca Battocchio of her first experience at a trappers' convention, “You can imagine my intrigue when I found myself amongst a group of women trappers at the convention. These women were not passive onlookers – they were on the board of directors, they were role models and they were revered icons.”

There has always been quite the female presence in the trapping world. However, female numbers certainly have been on the rise and I for one am proud to see these numbers increase.

TAF: The future of fur trapping in North America rests with the next generation. Is it secure? Are enough young people taking up trapping, and if not, how can they be encouraged? Are currently low prices for wild furs affecting recruitment of young trappers?

Katie Ball: There are plenty of youth that are taking up the reins as trappers thanks to families getting them out on the land and making a pleasant experience that they will carry on for a lifetime. However, it's the people and youth that do not have this inherent advantage that we need to get out there.

“Take a kid trapping” is by far one of my favourite slogans. But take your kid and their friend. Take your niece or nephew and their friends. Get your neighbours and family friends to experience the great outdoors as well. There is no time like the present. It’s not just about trapping; educating people and creating allies will ensure that our heritage is passed on to future generations.

When it comes to fur prices, as my father always says, “We don’t do this for the money. We do it because we love it." The fresh air, nature, exercise and pride in knowing we are a part of a delicate balance – these are just a few reasons why we enjoy time spent trapping.

But if you want to look at it monetarily, fur prices have always fluctuated, depending on trends, politics, and the state of financial security. One factor that I find has been driving my business since I started is naturally sourced materials. People are not only looking at where their food comes from these days, but also where their clothes come from and what they're made of. People are choosing to get away from petrol-based products and are actively seeking out ethically sourced and eco-friendly products. I believe that we can start to see an increase in demand just from this trend alone in the near future.

TAF: Let's close on a lighter note. Trappers always seem to have a bunch of stories to tell. Can you share some of your memorable moments?

Katie Ball: Every day presents a new challenge, experience and memory: feeding the whiskey jacks from my toes as a kid, working in the skinning room with my dad in the dead of winter. Going out with my partner Richard has become a new and wondrous adventure, sharing our passion for the outdoors and learning from each other along the way.

Driving down the winter road with my uncle looking for signs of moose, when all of a sudden we were flanked on both sides by a wolf pack. They ran just like dolphins on either side of a boat. This lasted for about 3 km, then they disappeared as fast as they came.

Otters swimming around the boat while collecting our minnow traps.

So many events, but they always come out during conversation around the fire.

June saw fur very much on the agenda in the UK, where the government was obliged to debate a proposal to…

Read More

June saw fur very much on the agenda in the UK, where the government was obliged to debate a proposal to ban all fur imports on leaving the EU next year, after receiving a petition with 425,000 signatures. The opposition Labour Party vowed to pass such a ban if given the chance, while its members vied for the headlines with celebrities like Brian May, Judi Dench, Ricky Gervais and Andy Murray. One Labour MP even likened wearing fur to wearing a swastika.

But while anti-fur tirades dominated column inches and air time, the media didn't just roll over. The BBC took a sympathetic look at mink farming in Denmark, and raised the issue now on everyone's mind of our excessive use of plastic, including fake fur. Even the tabloids are condemning fake fur, with the Daily Mail stating, "'Animal-friendly' fashion alternatives could do more harm to the environment than fur and leather-based clothing." (In fairness, though, the Mail is happy to bash anything, including real fur.)

As anticipated, the Conservative government said it has no plans to ban fur imports, but the future is far from secure if Labour wins the next general election, scheduled for 2022.

In other European news, vegan terrorists are now picking on family butchers. We reported in May how a butcher in England had its windows daubed with paint and got death threats all the way from Australia. Now French butchers are so sick of vegans that they're demanding government protection. Targeting butchers is not just a European thing, though, as this Berkeley, California butcher found out last year.

And on the subject of food fascism, a food lawyer (yes, such a job exists!) says we should follow California's foie gras ban closely. The Supreme Court, no less, has been asked to hear an appeal from producers about a circuit court ruling reinstating the ban. "This is a court case about much more than foie gras," Baylen Linnekin told the Orange County Register. "It concerns the future of beef, poultry, pork, and other foods eaten by nearly every American."

When animal users are not countering ignorant and often untruthful attacks from animal rightists, we're searching for answers to tough questions. When it comes to knowing your opponent, here's a thought-provoking piece in The New Republic entitled "The truth about the 'vegan lobby'." "It has long been demonized by conservatives – and even some vegans themselves – but does it really exist?" asks Emily Atkin.

Truth About Fur's senior researcher Alan Herscovici examined "The truth about 'fur free' designer brands". Have they really developed a dislike for fur, or are there other forces at work?

Also on our blog, conservationist and environmental social scientist Paul McCarney asked the tough question of whether anthropomorphism is good or bad for conservation. And on a related note, Roy Graber at WATTAgNet says farmers et al. should "Stop saying animals are our friends." "Often when the food and agriculture industry depicts overly happy visions of livestock and poultry, it reinforces unrealistic expectations," he writes.

Meanwhile, it's easy for animal users who produce food and clothing to forget that medical researchers have been under attack for decades and the problem shows no signs of abating. The Daily Bruin published a series of responses by researchers to activists, defending the use of animals in studies. Said one, "It is difficult to have a conversation with people who believe that human and animal lives should be weighed equally."

If you ever have to argue why we don't need to treat animals quite as well as humans and you're not sure what to say, Juan Carlos Marvizon, Ph.D. provides this scientific explanation in Speaking of Research.

Ontarians have been hogging the trapping headlines of late, in a nice way.

On Truth About Fur's blog, Ontario trapper Jim Gibb described how to stay busy with wild fur prices so depressed, in "Skunk under your deck? Call a certified trapper".

"Irrepressible" Ontario trapper and designer Katie Ball was interviewed by the International Fur Federation. She's a busy beaver with a résumé that includes the Northwestern Fur Trappers Association, the Ontario Fur Managers Federation, and the Northwestern Ontario Sportsmen's Alliance. On top of all that, she runs a fur design and manufacturing business, Silver Cedar Studio.

And if you want to trap in Ontario but come from out-of-state – or in this case a whole different country – be sure to follow local regulations. These Minnesota trappers were fined $6,000 for trapping violations in Ontario.

In other trapping news, the Northwest Territories are having trouble with too many beavers, so the government has raised the bounty from $50 last year to $100. The offer ended June 10, so plan for 2019. This is called a marketing incentive, not a cull, and trappers must show evidence that the meat or pelt are being used.

It's unfortunate, of course, that so many animal activists now behave so badly, but the "good" news is that law enforcement and society at large are not giving them a free ride.

In Utah, activists have been charged by the FBI for stealing piglets from a farm. This activist has been charged with breaking into five Ontario mink farms. And in Australia, these ones have been charged with animal cruelty for allegedly injuring and killing several hens after a break-in.

In Florida, an angry sheriff brought attention to the old problem of activists releasing undercover videos of alleged animal cruelty to the media rather than to law enforcement, in this case enabling the perpetrators to flee the state. As always we ask ourselves, do they really want to protect animals or simply grab media attention?

Last but not least, it's tempting to laugh at the fate of these Direct Action Everywhere protesters who crashed a BBQ challenge in San Francisco, only to be booed, heckled and taunted with meat by the participants. What did they expect? And if you think that's nuts, check out the video of the lady protesting "cruel" conditions on chicken farms by lying in a pile of poop – in California, of course!

It’s time for our May news roundup and we are going to start by talking footwear – vegan footwear to…

Read More

It's time for our May news roundup and we are going to start by talking footwear – vegan footwear to be exact. According to Footwear News, vegan footwear is on the rise due to demand from millennials, and improvements in material quality. No matter how much the quality of plastic shoes improves, they are still made from plastic, which is made from petroleum and never fully biodegrades. There are some organic alternatives making it to market, such as pineapple leather, but we still don't know whether the production processes used to create this material are safe and sustainable.

And sustainability is a very important topic these days, in particular within the fashion industry. Unfortunately designers like Stella McCartney, who consider themselves spokespeople for sustainability, still don't seem to understand the definition of the word. This is an interesting article on whether real or faux fur is better for the planet, this article highlights the problems with faux fur, and this one debates whether feathers are more or less ethical than fur (pictured).

We think feathers are less ethical, because fur is often used as winter clothing, whereas feathers are almost exclusively used as decoration on garments. (Down stuffing is the obvious exception.) If you are going to use animals for clothing, make sure it is for a good reason, right? That said, we'll take feathers as decoration any day over plastic beads.

Things are getting heated on the animal rights front, especially for a family butcher who has come under attack from vegan animal rights activists in the UK. Activists claim to be compassionate, but we aren't sure how graffiti and death threats towards a small, independent butcher can be considered so.

This article calls out pipeline protesters who align themselves with Greenpeace, without considering the harm that the organisation has done to the Inuit through its anti-sealing campaigns.

A topic that is close to our hearts has made a lot of headlines recently: animal rights vs. animal welfare. The headlines that caught our eye were these: "How consumers confuse animal rights with animal welfare" and "Proposed pet crackdown confused animal welfare with animal rights". Meanwhile this piece explores the concept of conservation and how it has nothing to do with animal rights, and this one explains that consumers care about animal welfare, but they still want to eat meat and wear leather.

Coyotes are back in the headlines for attacking children and being the subject of poorly thought-through "management plans". On the blog, we looked at how the urbanisation of predators, and in particular coyotes (pictured), may change city dwellers' thoughts on trapping. And while we are talking about animals not being welcome, it's worth reading these pieces about nutria populations skyrocketing in California, and Canadian beavers destroying South America.

But let's forget about vegan footwear and criminal activists and end this week's roundup with some links we loved:

This author believes grass-fed beef is probably the most vegan food in the supermarket.

Demand for fur and leather in the US is forecast to reach $13 billion by 2022. Take that, activists!

Conservationist Finn, a yellow Labrador, is helping save penguins by sniffing out rabbits (pictured).

On our blog, From Donald Duck to Zootopia: 70 years of cartoon fur.

Fur has been making the headlines more often than usual, and we are very happy to see the media questioning the…

Read More

Fur has been making the headlines more often than usual, and we are very happy to see the media questioning the use of faux fur. While the media aren't exactly singing praise for real fur, we are starting to see a consistent message that faux fur may not be a viable substitute for the real thing, especially since they are finding plastic microfibre pollution in water, caused in part by our use of synthetic fabrics. Of course us fur folk know this and it's part of our campaigning, but the fact that the media are regularly mentioning this is certainly positive for the trade.

Check out articles by Drapers, ABC, and Refinery 29. Not all of these articles are pro fur, but at least people are beginning to understand the damage caused by fake fur. Unfortunately this piece by Forbes failed to call out the companies who are dropping real fur in the name of sustainability, when we all know that real fur is so much more sustainable than the alternative.

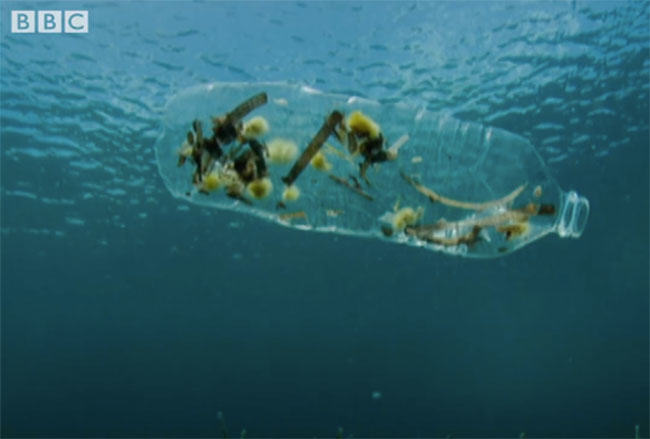

The team at Truth About Fur also did a piece about how a fur could be the most sustainable material in your closet, and if you want some clarification on how microfibres (from materials such as faux fur) pollute our oceans, then this video does a great job explaining it. Since we are on the topic of microfibre pollution, it’s worth checking out this BBC video about plastic pollution (pictured), or this podcast from CBC’s The Current where they discuss the issue in depth.

Now that you are convinced that real fur is far superior to faux fur, are you considering buying one? Our guide to choosing the right fur for you will give you a hand with your shopping. But be careful – there have been some isolated cases of real fur being labeled as fake. The fur industry’s stance on this matter is in agreement with animal rights activists (that’s a first): labelling needs to be accurate. Everyone has the right to know what they are buying. If you do end up getting yourself a beautiful new fur coat, here are some great tips on caring for it.

While they are still very much bent on ending the fur trade, animal rights activists have also been busy on other projects, and any fashion brand that thinks dropping fur will get them off its back should think again. For example, they want to stop the use of skins like crocodile and snake, leather, wool, and silk. (Prince Charles will certainly have an issue with that, since he's recently been promoting the benefits of wool.) Now PETA has luxury conglomerate LVMH in its cross hairs, pressuring it to stop using exotic skins.

Aside from fashion companies, the targets for bothersome activists seem to be endless. They're against dog-sledding, of course, and this article about PETA's campaign against the Iditarod is an interesting (and frustrating) read. They're trying to convince us to eat vegan ice cream, covering themselves in manure, and trying to get monkeys intellectual property rights. They're also feeling terribly sorry for themselves, so much so that they've given a name to the anxiety linked to being vegan – Vystopia.

It’s normal to be frustrated with activists trying to restrict our freedom of choice and force us into faux fur, but there is one story in particular that has really bothered us. You may have heard of the Toronto restaurant that reacted to vegan protesters by butchering and eating a deer leg in the restaurant’s front window. When the story hit the headlines across North America, we thought the activists would move on to the next unsuspecting small business. But instead, they told the restaurant owner that they would only be willing to cease protesting if he put a vegan slogan in the front window. The restaurant owner refused and referred to the threat as extortion – which we agree with. On the upside, the restaurant continues to get tons of free press as this saga continues.

A few other articles that caught our eye last month were this piece about the seal hunt, and some great trapper profiles, from Kansas and Labrador. We also found this very good read on how the declining numbers of hunters is threatening conservation (pictured). We certainly agree that it is time to start changing the way we talk about hunting, and trapping too.

Let’s end this month’s roundup with an update on what the animals have been up to:

The news is not good for caribou, as their numbers are declining.

Oregon is considering what to do with its growing sea lion population, which is having an impact on fish populations.

Belugas can communicate, and it's a lot more sophisticated than we thought.

Next time you check into a motel, make sure the occupant next door isn’t an alligator.

No one intelligent will be surprised to learn that this deer vasectomy program is a waste of money.

This coyote's tuition fees are really quite high.

Beware of moody geese who have just been through a breakup.

Cows and chicken duke it out to determine which should (and shouldn't) be eaten.

Choosing the best fur for you is like choosing a car. Most of us can’t afford a different car for…

Read More

Choosing the best fur for you is like choosing a car. Most of us can't afford a different car for every activity or need, so we pick the important ones – say, school runs and camping – and buy accordingly. Furs are the same. Unless we can afford a different fur for every occasion, we need to choose carefully with our personal lifestyles in mind.

The first question is easy: what will be your fur's primary function? As cars are to get from A to B, so furs are for keeping us warm.

But again as with cars, furs usually have to be multi-functional. Yes, we want to keep warm as we go about our daily activities, but we probably also want to look great on a night out. So the second question is often, how do we balance beauty with functionality?

Before you start picking out styles and fur types, ask yourself how you'll be wearing your fur. Will you be mushing dogs across Alaska (in which case comfort and warmth trump sophisticated styling), or will you be sipping martinis on the patio in California?

Apart from warmth and beauty, some other considerations include:

So let's run through some scenarios and help decide the best fur for you.

Most furs have two types of hair – long, shiny guard hairs and short, fine underfur. The guard hairs are what we usually see, and they protect the animal from branches and other obstacles, while the dense, soft underfur does most of the insulating. So furs with delicate guard hairs, like fox, or none at all, like chinchilla, can be lightweight and warm but are fragile, requiring lots of tender loving care.

The most popular furs – including mink, beaver, marten (Canadian sable), coyote, and others – combine beautiful, protective guard hair with the warmth of soft, dense underfur.

Many furs (mink, beaver and others) are now "plucked", meaning that the guard hairs have been removed, and/or "sheared" down to the height of the underfur or shorter. This reduces the weight of the garment, and provides a sleeker silhouette while maintaining much of the warmth.

A shearling coat is made from sheepskin, with the wool sheared down to reduce bulkiness. (Think Uggs.) Shearling is often worn "reversed", with the fur side in, against the body, increasing warmth. This is how most furs were once worn when warmth was the primary concern. In fact, our word "fur" comes from the Old French "fourrer", literally meaning "stuffed".

Some furs (cow, calf and seal) are called "flat" furs because they have no underfur, only guard hairs. While beautiful, these furs are not much warmer than a good leather coat.

Caribou, worn by traditional hunters in the Arctic regions, is remarkably warm because it has hollow guard hairs, but that's not something you're likely to find at your local fur store or fashion boutique. In any case, it makes you look like, well, a caribou.

In summary, if keeping warm is absolutely paramount in your decision-making, check out what the pros use: mushers, polar explorers, and ice fishermen. But if you want to stay cozy while looking great in normal winter conditions, most popular furs will do the job.

Scenario #1: Ice-fishing in Nunavut. You’re dressing to stay alive, so a knee-length caribou parka with sealskin boots are perfect. If you can't find a caribou parka, try one with a rugged fabric shell filled with goose down, and fur trim on the cuffs, hem and hood to keep the wind at bay. Wolverine is considered by Arctic Inuit to be the most effective hood ruff, but wolf, coyote or fox also work well. Research suggests that the uneven length of natural fur hairs disrupts air currents that can rob heat from around the face. Whatever the reason, a fur-trimmed hood is a "must" in cold temperatures; it really works.

#2: Après ski. You want to be warm and look spectacular, while doing nothing more strenuous than raising your glass. For the ladies, didn't Audrey Hepburn look great in Charade in sheared mink with a matching pillbox hat and giant sunglasses? Mink has very dense underfur, so even with the guard hairs sheared, you'll still be toasty. For really chilly evenings, consider a fox or, better still, a chinchilla jacket. Despite being ultra-lightweight and super soft, chinchilla has extraordinarily dense underfur. Pair yourself with a ruggedly handsome man in coyote or long-hair (unsheared) beaver for the full experience!

Keeping dry is part of keeping warm, because being wet greatly increases the wind chill effect. Underfur that is unprotected by sturdy guard hairs absorbs water, so if you're expecting damp weather, avoid chinchilla and rabbit, as well as furs that have been sheared or plucked. If you expect your apparel to be exposed to rain very often, you have three smart choices: flat fur, a "reversed" fur or fur lining, or fur with plentiful, long guard hairs.

Flat furs are the most water-resistant of all furs because they are nothing but guard hairs. The most durable of these is sealskin. Sometimes called “nature’s raincoat”, sealskin is so waterproof it has been used to make kayaks! But remember that because flat furs have no underfur, they are not that warm. Also, because the leather is quite thick, they are not light-weight, and are not suited to figure-hugging garments. (Note: Sealskin cannot be sold or imported into the US. This law was implemented in 1972, before modern regulations were in place to ensure sustainable hunting practices; it has unfortunately not yet been amended.)

Another way to keep warm and dry is to wear a reversed fur, or a jacket made with a water-resistant material and a fur lining. The most common reversed fur is shearling. Once bulky (think WWI aviator jackets), they are now made in a wide range of beautiful and sophisticated styles. Fur-lined raincoats or jackets can be worn year-round if you opt for a removable lining.

While full fur coats are not ideal for heavy rain, most good-quality beaver, muskrat, marten and other furs have long guard hairs whose natural oiliness repels water to a certain extent. If your furs get wet, never dry them near radiators or intense heat. Just shake off excess water and hang your garment to dry slowly with good ventilation. If your fur gets really soaked, it's usually best to consult a professional furrier.

In this age of fast, disposable fashion, it's gratifying that most furs can last for decades, especially with professional cleaning and storage. But some are more durable than others. The least durable are furs without strong guard hairs, such as rabbit and chinchilla, which may shed if rubbed a lot (think shoulder bag straps). The most durable are otter, beaver, and mink, with raccoon, coyote, and marten not far behind.

Natural furs tend to last longer than those that have been sheared, plucked, or dyed.

So, you want a jacket that can survive 20 years of real-life use before being passed on to your son or daughter? Mink is hard to beat, but you can also try long-hair or sheared beaver, marten, coyote, raccoon, or fisher.

Are you an attention grabber, or do you prefer to be discreet?

If you’ve just won Best Actress and want the world to know, a long-haired fur is for you. Associated with flash and glamour, nothing gives the movie star / rapper look like a fox coat, with its long, shiny guard hairs and spectacular natural colours. For men, long-hair beaver, fisher and coyote are bulkier and coarser, and often used for parka trim, but in a full-length coat give instant Mountain Man credibility.

For more sophisticated elegance, nothing beats mink. But sheared furs – or a fur-lined jacket or parka – also give you the luxury and warmth of fur without making a big deal about it.

For those who want something new, technological advances mean designers now have more room for creative expression than ever before. The classic mink coat has been reinvented for a more modern look, but all furs can now be transformed with shearing, leathering, knitting, intarsia, dyeing and many other techniques. Sheared mink can be made so light and supple, just dye it green and people will wonder what exotic new fabric you're wearing! Knitted fur is also very light, and as flexible as a woollen sweater.

Few fur fans can afford a $100,000 full-length chinchilla coat like Floyd Mayweather, but don't be discouraged. Entry-level fur garments have two fewer zeroes, and accessories are half that again.

The main factors determining cost are the type of fur, the quality of the pelts, the size of the garment, and the processing and manufacturing techniques required to make it. The price of the same fur type can vary widely, depending on the quality of the pelts used and the workmanship involved. Top-quality mink, sable, marten (Canadian sable), fisher, bobcat, lynx, and chinchilla are some higher-priced furs.