February Fur News: Fashion Week Protests and Extreme Vegans

by Truth About Fur, voice of the North American fur tradeIt’s time for our roundup of February’s fur news stories, and it makes sense to start with the catwalk shows…

Read More

It’s time for our roundup of February’s fur news stories, and it makes sense to start with the catwalk shows…

Read More

It's time for our roundup of February's fur news stories, and it makes sense to start with the catwalk shows and the inevitable fashion week protests. With fashion shows come protesters, trying to push their animal rights agenda on the general public. As usual, their protests were chaotic and not very effective. One activist in London stormed a catwalk show that did not even contain any fur. Meanwhile, Dennis Basso (a designer best known for his furs) showed a beautifully furry collection, and Elle says that fur sweatshirts are now a thing (pictured). We can get on board with that.

WWD did an interesting interview with Tom Ford, who made it clear that he thought fake fur was very damaging for the environment (so why is he using it, then?), but claims that he will now only offer furs that are by-products of the meat industry. Let's see how long this new strategy lasts. His most interesting comment was that "I have a customer who is very used to wearing leather and fur; it’s a part of our business." It's the reason why brands keep coming back to fur: FUR SELLS.

And speaking of fur selling, Truth About Fur's blog post last week looked at the future of fur retailing, and how some stores are adapting their sales and marketing strategies to the modern consumer.

The Winter Olympics ended last week and we were thrilled when we heard that Samuel Girard, who won bronze in speed skating, is also a proud trapper. He's not alone in taking pride in what he does, of course: this trapper says trapping is nostalgic and "in his blood", while these trappers play a role in bobcat conservation and dealing with beaver issues. And trappers are also the ones who put the "fur" in Alaska's Fur Rondy - here's why. It's not all fun though. This is a terrifying story (with a happy ending) about a trapper whose snowmobile got stuck and was forced to spend the night outside in minus 50℃.

There were some unexpected headlines involving animal rights activist groups last month. The Humane Society of the United States's CEO, Wayne Pacelle, resigned over sexual harassment claims. Apparently this is not unusual, in fact, it appears to be quite common in the animal rights movement. And yet these women go topless (pictured) at fashion week protests, and the movement continues to use degrading imagery of women in its campaigns. And, this certainly hasn't stopped these people accusing farmers of being rapists and sending them death threats. How about we take the sex, nudity, and harassment out of this argument, and argue our causes with facts? There's no doubt in our mind that vegans hurt their case by being too extreme, and the same could be said for the whole animal rights movement.

Here are a few more articles from February that are worth a read:

Fake fur is worse than real fur (duh).

Whales are being threatened by microplastics. (When will we stop with these horrible synthetic materials?)

A nude activist says she doesn't need clothes because animals don't have them. (This is even more ridiculous than the fashion week protests at fur-free shows.)

The ethics of killing animals is complicated (though you already knew that).

Try and avoid bringing your emotional support peacock on a flight. (He won't be allowed on the plane.)

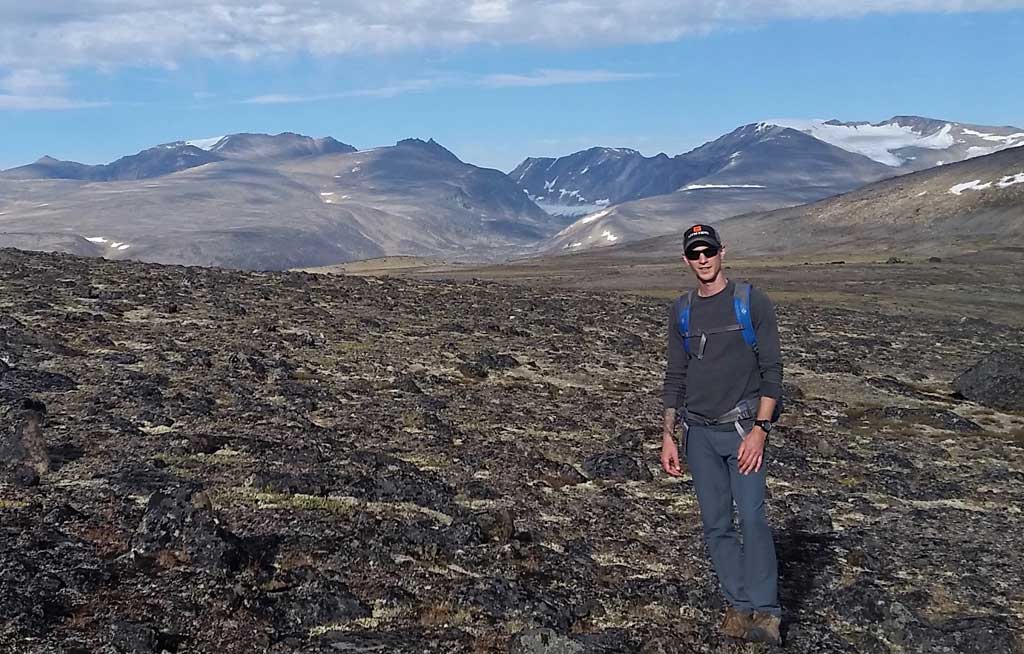

Lastly, It is with a sad heart that we learned this week about the sudden passing of the legendary Canadian trapper, Alcide Giroux. Alcide (pictured above) was a leader in the development of humane trapping methods. He was also tireless in promoting recognition of trappers as true conservationists and front-line guardians of nature. Alcide learned his bushcraft from his Métis father, a man he liked to say had a GPS in his brain – and the man he credits with teaching him the importance of promoting respect and animal welfare in trapping. At a time when we are working to increase public understanding of the important role played by trappers in environmental conservation, we owe much to Alcide’s pioneering efforts as an important leader and spokesperson for the trapping community. Rest in peace, old friend.

Like any business, fur retailing has its challenges, and some would say the challenges have never been tougher. But could…

Read More

Like any business, fur retailing has its challenges, and some would say the challenges have never been tougher. But could there also be exciting opportunities for furriers who figure out how to navigate the brave new world of retailing that is emerging?

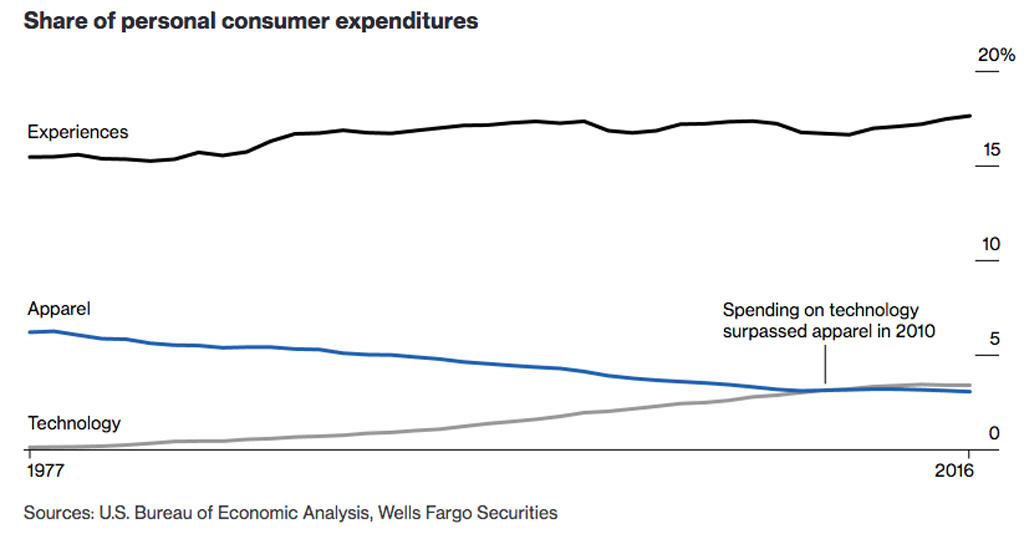

Let’s first take a quick look at the challenges. In "The Death of Clothing", journalists at Bloomberg.com recently argued that the problems now plaguing apparel retailing go deeper than the ferocious competition from Amazon and other on-line retailers. The more profound problem is that consumers are spending less and less on clothing: “In 1977, clothing accounted for 6.2 percent of US household spending. ... Four decades later, it’s plummeted to half that.”

In part, reduced spending on apparel reflects the success of the industry in lowering costs through off-shore production, vertical integration and other competitive strategies. But the decline also results from more casual lifestyles. With about half of Americans now saying they can wear jeans to their professional offices, there is less need to buy separate wardrobes for work and play.

It is clear that “dressing down” also has an impact on the fur business. And the fur trade is also dealing with animal activists, aging retailers, under-financed businesses with too little money for advertising, and other serious problems.

So where is the good news for fur retailers in this gloomy scenario?

For one thing, Baltimore, Maryland furrier Richard Swartz points out, even the industry's problems provide opportunities. "Unlike other businesses that have dwindled from lack of interest, the fur trade has received lots of attention over the last decades: attention has come from our opponents, as well as from fashion designers, celebrities wearing fur, and even the occasional large heist."

As leaders of Greenpeace used to say: "Who cares what they write about us, so long as they spell our name right?"

Three of the fur trade's traditional retail advantages also continue, says Swartz: "We are selling a blind item; we are selling many one-off items; and we sell services that not only generate cash flow, but also promote new sales and customer engagement."

In other words, bricks-and-mortar fur retailers have a certain degree of protection from on-line marketers because fur apparel is not mass-produced or standardized, so consumers must come into the store to try on a coat or jacket. And evaluating fur requires specialized training and experience; consumers rely on the furrier’s expert knowledge (and reputation) to ensure they are receiving value for their money. Not least important, fur apparel requires on-going in-store maintenance, including off-season storage, cleaning, repairs and remodeling, which brings customers back into the store at regular intervals.

But these protections alone are not enough to assure success. "I believe that the success of each individual retailer or retail group -- and indeed the retail trade as a whole -- will be decided by the degree to which they can reinvent themselves for today's reality," says Swartz.

To profit from the new opportunities, in fact, retailers will have to learn new skills that allow them to run their businesses and market fur products in new ways.

One retail furrier who is exploring the potential of new technologies is Stewart Chadnick of Pat Flesher Furs, in Ottawa. He recently hosted 12 local bloggers for an exciting, hands-on fur experience in his store.

“We greeted the bloggers with a nice selection of wine and hors d’oeuvres while I presented a brief history of our store and an overview of the fur business. I had set up a big TV monitor and showed them the Fur Trade in Two Minutes Flat video from the home page of TruthAboutFur.com as an introduction. I followed that up with the new sustainability video produced by the International Fur Federation. The two videos answered many of their questions and stimulated some interesting discussion.

“After a tour of the store and vault, we took them into our workshop where we had prepared everything they needed to make their own fur pom-poms. We had a lot of fun and they loved it. Several were blogging right from the workshop!” says Chadnick.

All the bloggers posted very positive accounts of their visit, which resulted in several new customers coming into the store in the following days. Great, you may say, but how many furriers have the social media skills to organize a bloggers event? Chadnick is the first to admit that he doesn’t either.

“I know I will never understand social media well enough to use it effectively,” says Chadnick. “So my marketing agency set up our Facebook page and Instagram account. We meet weekly to discuss story ideas and what we’re doing, and they were the ones who made contact with the bloggers and suggested inviting them into the store. We all enjoyed the evening, the ladies had a great story to blog about, and after the event our page registered dozens of new followers. It’s win-win.”

Chadnick also produced a small brochure for the bloggers about why fur is an ethical choice, using information he took from TruthAboutFur.com.

“The website is a fabulous resource for retailers,” says Chadnick. “Everything we need for educating and reassuring consumers is there. And young people are very interested in our environmental story.”

The bloggers’ event at Pat Flesher Furs provides a number of important lessons for retail furriers seeking success in today’s fast-changing marketplace:

Retailing is changing, and the way fur is marketed is changing too, as I learned recently from a journalist researching retailing trends in Quebec. She told me that the furriers she had spoken with are selling more small pieces and accessories, and they are integrating a broader product mix, becoming more like outerwear stores or fashion boutiques. But she was impressed to learn that several now also make a point of promoting the environmental sustainability of fur as an important selling feature.

As consumers become more aware of the environmental problems caused by “fast fashion” and petroleum-based synthetics, the sustainability credentials of fur will clearly become more important …

And perhaps this is the best news of all as we plan for the future of fur retailing. Because as young people – and all consumers – become more aware of the environmental problems caused by “fast fashion” and petroleum-based synthetics, the sustainability credentials of fur will become even more important and appreciated.

In fact, the environmental benefits of using real fur may well be emerging as one of our most important “Unique Selling Propositions” (USP). After being so unfairly scapegoated for so many years, fur may finally be recognized as not only warm and beautiful, but also as an environmentally responsible and ethical clothing choice. Now that’s a powerful marketing story!

If you have ideas about new ways to market fur products at retail, please post a comment below; we’d love to hear from you.

There is a saying that the only things we all have in common are birth, death, and taxes. If there…

Read More

There is a saying that the only things we all have in common are birth, death, and taxes. If there is a fourth thing common to every human being on the planet, it is that human lives depend on killing animals. This is true for hunters, trappers, animal-rights activists, vegans, and everyone else, regardless of where we live, our cultural differences, or our lifestyle choices. I don’t say this out of callousness or for shock value; rather, to put every one of us on the same page, in the same common history book of our species. If only for a moment.

I would like to think we can all have the humility and honesty to acknowledge the fact that human life depends on the death of animals, despite how uncomfortable we may be with this truth. To that end, I won’t spend time going over the various ways that human civilizations and settlements displace wildlife and affect habitat. Many of us do our best to reduce our direct and indirect impacts on the natural world, but close as they may come, these impacts will never reach zero. None of us is exempt from the effects of human civilization on wildlife. The task as I see it is not so much to accept or refute this fact, but rather to reflect on our own understandings of it and what it means to have a relationship with animals that involves death.

One of the most common points of disagreement in conversations about animal ethics centers on the consumptive uses of animals. Concerns over the treatment of both wild and domestic animals and their use for food, fur, and other products is an important conversation and one that I believe should be of highest ethical importance to human beings; however, we often bring a set of unstated and embedded assumptions to these discussions that need to be examined if we are to ever truly understand our own ethics, have productive conversations with others, and be effective at conservation.

One of the underlying assumptions that we need to critically reflect on in discussions over the use of animals is the very concept of killing. Our individual and collective understanding of the moral defensibility in killing animals and the nature of the human-animal relationship that is established through an interaction that involves killing are informed by our views of death itself.

In discussing the ethics around the use of animals, we must be thoughtful to the fact that understandings of central concepts such as death and killing are not universal. Cultures throughout the world have vastly different understandings of what it means to die, what happens after death, the relationship between life and death, and therefore what it means on a deep ethical level to kill an animal. Therefore, we cannot approach discussions with the assumption that we all understand the moral foundations of the topic in the same way. More importantly, we must be conscious not to assume that our own culturally-grounded way of understanding these concepts is correct. To approach conversations of such ethical gravity in that way is to demonstrate a sense of cultural centrism that has proven dangerous to both human cultures and ecological systems in the past.

It is possible that some of us have never really taken the time to deeply reflect on our own relationship with the death of wild animals. For the majority of the world that lives in urban centers and will never be personally involved in killing an animal, thinking about this may never be a necessity. In his examination of humanity’s relationship with nature and our own natural history, the author J.B. MacKinnon in The Once and Future World poignantly describes watching a grizzly bear feed on an elk calf. MacKinnon reflects on nature’s experience with death: “springtime in Yellowstone is not the season of gambolling fox kits ... but of the hungry bear and wary bison. Of death, that ordinary horror”. Killing is all around us all the time; whether and how we choose to understand that fact of life on a primal and philosophical level is our choice. MacKinnon goes on to suggest that “to endure among other species, you must experience the world as a place you share with them”. If we wish to share the world with wild creatures and natural processes, we owe it to ourselves to engage with them on their terms.

Consider the fact that most modern human beings eat next to nothing that is hunted or gathered from the terrestrial surface of the earth. This is an outcome that would strike our ancestors as bizarre if not apocalyptic, and yet it can’t be said to be the product of choice. We drifted to this point, generation by generation.

J.B. MacKinnon in "The Once and Future World"

Let me clear about what this is not. I dislike dead-end arguments in discussions about ethics. It might be tempting to dispute the suggestion that death and killing are equal parts culturally contingent concepts and natural parts of the world, as simply a hunter’s way of justifying his own actions. That has been suggested to me before and I will humour that idea, but it is far more complex than that. Human ethics change over time to incorporate new ideas and knowledge and this changing is precisely what keeps ethics strong and meaningful. Therefore, the suggestion that any single argument can settle an ethical debate is unconvincing at best and suspicious at worst. This is not a claim that killing wildlife is morally defensible because “we have always done it”. I don’t believe that historical precedent justifies continued practice. However, in the same way that history does not justify the present, neither can it be disregarded as irrelevant. So I do think that the long history of interaction between humans and wildlife that has always involved a predator-prey relationship makes the conversation worth having in light of that history and not in exclusion of it. Cultures and belief systems are built upon shared experiences and give rise to knowledge systems and worldviews that are rooted in the places of those experiences. It is the diversity of these cultures that contributes to different understandings of what it means to kill an animal and our conversations on the ethics of killing and using animals must include space for the wide variety of cultural views that exist in the world.

Our evaluation of the ethics in killing animals for our own uses is bound to be informed in some measure by our understanding of what death means and the subsequent emotions we attach to dying and being dead. It is helpful to consider examples of different cultural understandings of death. These contrasting worldviews around death mean that understandings about the relationship enacted with an animal in the act of killing it can also be very different. Bear in mind that I am highlighting two examples here and that the diversity of human cultural perspectives is nearly as wide and deep as the biodiversity of the natural world itself.

The dread of something after death, / The undiscover’d country

"Hamlet" by William Shakespeare

The Reverend Charles A. Curran, Professor at Loyola University of Chicago, discusses an understanding of death informed by Judaeo-Christian traditions. Curran explains that in Christian worldviews, death “immediately invokes in us the emotion of fear”. This fear of death is not so much a fear of the physical process of dying, but rather “the notion of the beyond that the word ‘death’ brings to us, because its fear is a fear of the beyond”. This fear is also related to the gravity of having to weigh the morality of our lives and what Curran describes as an “extreme ego anxiety about passing into nothingness” – the fear of irrelevance and being forgotten. There are other more obvious teachings in Christianity about what killing means for the morality of our own lives.

A Judaeo-Christian view of death has been imprinted on some of Western culture’s most influential pieces of art and literature, and it is perhaps only natural that our feelings around our own death would be imparted onto animals when we consider their death. Daniel E. Van Tassel, Professor of English at Muskingum College, notes “the stamp of such Christian views of death” in the “expression of fear at the imminence of death” among a number of Shakespeare’s characters. Van Tassel cites three reasons to fear death in Judaeo-Christian traditions: we fear losing the enjoyment of life and worldly pleasures, the emotional and physical pain that comes with death, and the eternal misery after death. In considering how such a culturally-dominant, if latent and subconscious, understanding of death may impact our view of killing animals, we can certainly identify in animal-rights and other anti-hunting/trapping campaigns references to the second fear of death: fear about the pain and suffering that killing brings. In this fear we see MacKinnon’s characterization of death, “that ordinary horror”.

Like other northern hunting peoples, many Yukon First Nation people conceive of hunting as a reciprocal social relationship between humans and animals.

Paul Nadasdy, in "Agricultural metaphors and the politics of wildlife management in the Yukon".

In a book chapter I have frequently returned to in discussions over human-animal relationships, Paul Nadasdy, Associate Professor of Anthropology at Cornell University, discusses the contrasts between Western and Yukon First Nations’ understandings of the concept of wildlife management, focusing particularly on contrasting notions of ownership and control between cultures. Within a Yukon First Nations worldview, humans and animals interact on the basis of a reciprocal social relationship defined by the need to uphold certain responsibilities. Humans hunt wildlife but do so within the context of specific practices designed to maintain the relationship, practices that vary between cultures, but “commonly include the observance of food taboos, ritual feasts, and prescribed methods for disposing of animal remains, as well as injunctions against overhunting and talking badly about, or playing with, animals”. Maintaining the social relationship one has with animals is of utmost importance and in this particular cultural worldview, involves killing.

There is an element of control and agency that is important in understanding the contrast between different worldviews. In a Western worldview, humans are most commonly positioned above and in control of nature: the world is here to be used by humans. In, for example, a Yukon First Nations worldview, animals have agency and can choose not to present themselves to human hunters. Humans must therefore fulfill certain social obligations towards animals and these obligations are often carried out through hunting. The concept of killing and what it means to kill an animal is thus conceived of quite differently in a Yukon First Nations context than one dominated by Western knowledge and cultural traditions.

The idea that there exists a plurality of knowledges informed by one’s culture must accompany us into ethical conversations and decision-making around the use of animals. We must remember that in many cultures, a context of respect and gratitude is the very the foundation of how humans have come to understand a relationship with animals that involves killing.

I am not a religious person and I would not even suggest that I am spiritual. I have come to understand my actions and morality on my own terms and I have tried to inform that understanding as much as possible by lessons in nature, though inspiration for this understanding can come from many places. I want to make it clear that caring deeply about wildlife is not dependent on religious or spiritual guidance; I have thought and felt deeply about both the individual animals I have killed and about the populations and species of which those individuals were a part. When I kill an animal, there is an intense and undeniable connection with that individual – from the moment I first see it to every single time I cook a portion of it – and there is also a connection with that animal that feels more historic, a sense of shared history on the landscape. Animal-rights campaigns often focus on individual animals that have been given human names. This kind of anthropomorphism often loses the ability to situate the relationship between human and animals on an evolutionary scale. For me, it is precisely the simultaneous feelings of intense personalization with an individual animal and a depersonalization with the awareness that there is a deeper historic interaction that we are a part of that gives the encounter so much meaning.

One thing that many of us can agree on is that healthy ecosystems and wildlife populations are critical for the survival of our species and this planet. We might also agree that maintaining healthy ecosystems and wildlife populations depends on human appreciation and valuation of those places and species and in order for humans to care about and take care of the natural world, they need a personal relationship with it. It may be that some wish to redefine the foundation of this relationship in a way that reflects changing social and cultural norms, but this cannot be taken for granted and this new foundation cannot be laid without conscious and thoughtful reflection, otherwise we risk losing the historic relationships within which both humans and animals have mutually evolved.

We may personally disagree with particular conservation policies or strategies, but it is imperative that we maintain our connections with animals and understand that there are cases where this connection takes place through an interaction that involves death. I personally consider ethical concerns about animal welfare as one of our most important considerations in killing animals. However, when engaging in discussions with one another over the ethics of using animals, we need to be conscious of the foundational assumptions on which these conversations are built. We need to identify and critically reflect on the culturally specific concepts we bring to our decision-making around killing and understand and respect that ethics are a sliding scale throughout the world.

In doing so, we may find that misunderstandings and disagreements run deeper than the specific applications and policies we find ourselves debating and that we gain much more from engaging with a plurality of ethical perspectives than from disregarding them.

It’s our first news roundup of 2018 and we want to start off the year asking this question: fake fur…

Read More

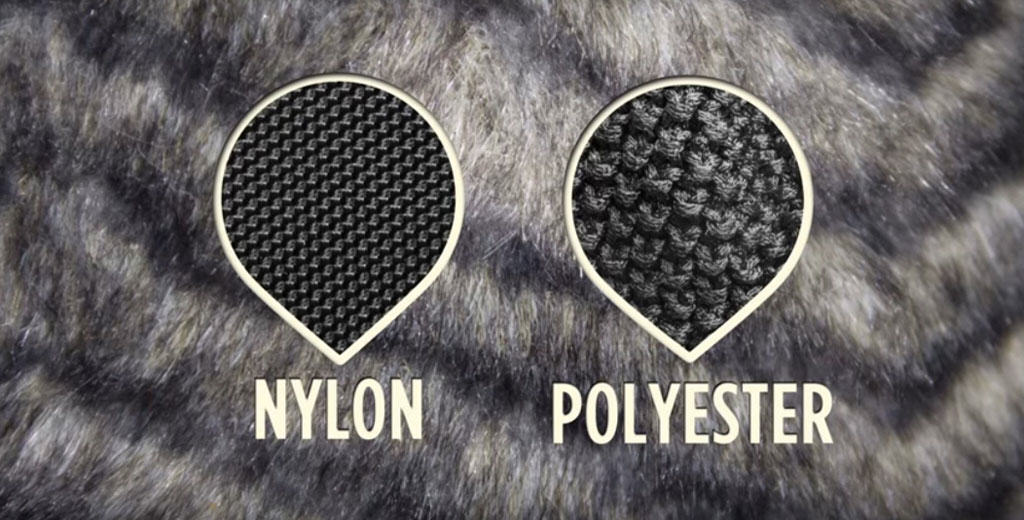

It's our first news roundup of 2018 and we want to start off the year asking this question: fake fur vs real fur, which is better? Well, all of us fur lovers know the answer but sadly a lot of people think that fake fur is a good alternative to real fur. Those same people also tend to care about the environment and want to protest pipelines, so it was time to set them straight. That's why the International Fur Federation produced this excellent video, highlighting the dangers of plastic pollution from synthetic fabrics. Fake fur vs real fur - it is obvious that real fur is the better choice for the environment and our planet. (Interested in the history of fake fur? This is worth reading.)

Speaking of the environment, the stewards of the land (otherwise known as trappers) are seeing some increases in auction prices, both at the Thompson Fur Tables and the Fur Harvesters Auction (pictured). But trapping isn't just about making money, it is also about passing down skills from one generation to the next, managing wildlife populations, returning to rural roots, and living off the land.

The trapline may seem very far away from a fur store in Manhattan, but the two are quite connected. Unfortunately for the furriers of NYC, rising retail rents are forcing some independent businesses to close down. If that's not bad enough, thefts of fur coats are also a threat.

But retailers are used to weathering challenging times, and it is not all bad news. British retail trade magazine Drapers surveyed some premium retailers and many of them named fur items as some of their bestsellers over the holidays. Speaking of the Brits, British Vogue had a fur ad in its pages recently, and the activists were not impressed. Maybe the magazine is finally realising that its selective no-fur policy is quite hypocritical when it frequently features exotic skins, sheepskin, and leather.

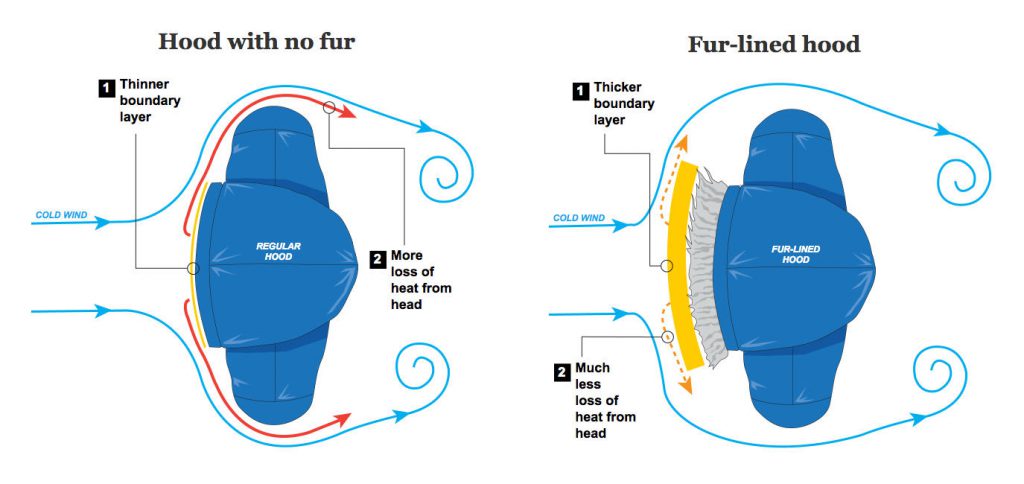

One of the main criticisms we hear from activists is that fur is often used as trims, and fur trims are not effective in keeping people warm. Finally, we have proof that this is not the case. There is a science behind why real fur hood trims are effective (pictured) and we explored that topic in a recent blog post about fur hood trims. That won't stop the activists trying to shut us down, but we hope that this war will be one of facts. Proof that fur trims are effective only strengthens our industry, and when it comes to fake fur vs real fur, the natural, biodegradable, sustainable option always wins.

Let's end this month's roundup with a few important news stories that caught our attention.

Here are ten organizations that you should never give donations to.

This Greenville fur company makes outfits for Hollywood.

Even if you are a vegetarian, you still have blood on your hands.

The fur industry is launching a global campaign to promote sustainable fur, and the environmental benefits of using real fur…

Read More

The fur industry is launching a global campaign to promote sustainable fur, and the environmental benefits of using real fur over petroleum-based synthetics, including fake fur.

A hard-hitting video produced by the International Fur Federation is being launched in key markets around the world. In the accompanying press release, Mark Oaten, CEO of the IFF said: “It’s time to call out the fake news about fake fur.” Fake fur is being promoted by animal activist groups as the ethical alternative to real fur.

Sustainable Fur, the campaign video, shows the environmental damage that is being caused by plastic-based fake fur and other synthetics. In North America, the video was prominently promoted on the website of Women’s Wear Daily for a week, before being distributed more widely. In addition to Canada and the US, the video is being promoted in China, Japan, Taiwan, Korea, Russia, Argentina, Brazil, and throughout Europe.

“Natural fur is the responsible choice when compared with fake fur or other synthetics,” said Mark Oaten.

“The consumer is being fed a constant diet of fake news by activists when it comes to fake fur,” he said. “Meanwhile, scientists are warning that plastics should be eliminated as much as possible from the retail chain.”

The video shows how fake furs and other synthetics are creating major environmental problems because they are made from fossil fuels (non-renewable resources) and are being linked to the release of microfibers into the environment.

“These are plastics that take decades to biodegrade – if they biodegrade at all – and we are now learning that they are entering the food chain and being consumed by marine life, and eventually by us,” said Oaten.

“Real fur is the sustainable alternative. It is natural and provides decades of use for the consumer.”

The video explains that farmed fur animals (primarily mink and fox) are fed left-overs from our own food supply – the parts of fish, pigs and chickens that humans don’t eat. The manure and other wastes from fur farming are composted to provide bio-fuels or natural fertilizers, completing the agricultural nutrient cycle. This is a much more sustainable and ethical alternative than dumping such wastes in landfills.

SEE ALSO: Fur farming: Nothing is wasted, at Truth About Fur

The production of wild fur is strictly regulated to ensure that only part of the naturally-produced surplus from abundant populations are used. This is an excellent example of the sustainable and responsible use of renewable natural resources, a key environmental conservation principle promoted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and other conservation authorities.

Many furbearing species must be culled to protect property, livestock, natural habitat and endangered prey species, or even human health, whether or not we use fur. Overpopulated beavers can flood farmland, forests, roads or homes. Overpopulated raccoons and foxes can promote the spread of rabies or other dangerous diseases. Coyotes are the number-one predator of young calves and lambs on ranches. Coyotes, raccoons and foxes must be controlled to protect vulnerable populations of ground-nesting birds and the eggs of endangered sea turtles.

SEE ALSO: Reasons we trap, at Truth About Fur

The new video campaign is being released as the fashion industry and consumers are beginning to discuss more seriously the environmental impact of our clothing choices. The confusion caused by animal activist campaigns became apparent when Gucci CEO Marco Bizzarri recently announced that his company would stop using fur “because of their commitment to sustainability”. As Truth About Fur explained in "Fur-free Gucci policy contradicts company's 'sustainability' claims", the brand's decision to turn away from fur reveals an astonishing misunderstanding of the real meaning of sustainability.

SEE ALSO: Sustainability: Why is Gucci so confused?

The first major campaign to promote the fur trade’s important sustainability credentials was launched by the pioneering website Furisgreen.com. This website has attracted considerable media attention, helping to spread the message. It is expected that the new IFF Sustainable Fur video will also generate media interest in response to press releases that were distributed simultaneously in North America, Europe and Asia.

To help spread the message, retailers, manufacturers and people in every sector of the fur and fashion industries are being encouraged to post the new IFF Sustainable Fur video on their websites and Facebook pages.

“At a time when consumers are becoming more interested in understanding the environmental impact of what we buy and wear, we have an excellent opportunity to explain why fur is a sustainable and responsible choice,” said Teresa Eloy, Managing Director of the Fur Council of Canada.

“This video presents some important facts about the environmental credentials of fur in a succinct and easy-to-understand way,” said Keith Kaplan, of the Fur Information Council of America. “This is an exciting campaign and we are encouraging retailers across the country to post and share this hard-hitting video.”

Welcome to Fur Trade Tales, our new series of real-life stories from real people of the fur trade. We kick…

Read More

Welcome to Fur Trade Tales, our new series of real-life stories from real people of the fur trade. We kick off with our first Trapline Tales, but look out for Fur Farm Tales, Furrier Tales, and more to come. If you'd like to contribute, please let us know at [email protected]

Everyone in the fur trade has tales to tell, and I am honoured that Alan Herscovici – the creator of Truth About Fur – thinks mine are worthy of launching Trapline Tales. It’s the least I can do. Alan has devoted his working life to the trade, sometimes at great personal cost, and has been a passionate spokesperson to the media on behalf of us all. We owe him a great debt of gratitude.

Today I run a company called Fur Canada, making a range of fur products, museum-quality taxidermy specimens, and traps, but my journey in the fur trade began long ago, in a place called the West Kootenay, in British Columbia. I grew up there in the 1960s and '70s, and it had to be the best childhood any kid could experience. With my parents and siblings, I learned the ways of living off the land. We grew every kind of vegetable, had milk cows, chickens, horses and beef cattle, and in winter I would assist my father on his fur trapline.

Every weekend during winter was a new experience. My father's trapline was 100 kilometres long, and it took us five years just to rotate every corner of it. In 1963, we also acquired the area's first snowmobile.

One day my mother and I were shopping in Nelson when I spotted a parked truck with two big, yellow snow-plowing machines on a trailer. "What are they?" my mother inquired of the gentleman attending them, who happened to be a distributor. He graciously explained how they worked and their advantages over snowshoeing. He called them "snowmobiles", and they were made by a Quebec company called Bombardier. She said her husband was a trapper and might be interested in one, so he followed us home. My father quickly took a liking to these machines, and since it was late, invited the gentleman to stay the night.

Next morning, my older brothers and father road-tested the machines, and by lunchtime the deal was made. We were the proud owners of a brand new Bombardier snowmobile! I still have it to this day, and one day will restore it to its original state.

During that winter and the next, the gentleman made follow-up visits in case repairs were needed. He was very impressed with my father and his success with the machine, because within that first winter, he had contracts with the power company and timber company to check on their power lines and spar tree equipment that was inaccessible in the back country.

On one of his visits he told my father that he was the sole distributor for Alberta and British Columbia, and the territory was now more than he could handle. Would my father like to take over the distributorship for BC? My father pondered for a moment and could only envision the excessive work ahead in promoting, selling and servicing the product during the trapping season – the most important part of the year for him. His answer was an emphatic "No!" I'm not sure he gave much thought to setting up his two teenage sons and me, then just six years old, in the snowmobile business, as fur trapping was his passion. You could say, there was a great missed opportunity for the family, as hindsight is always 20/20.

A few years later my father purchased another snowmobile. At this point Bombardier was selling them under the brand name Ski Doo, and our new Ski Doo was called an Olympic.

At 10 years old, I was operating our original Bombardier and my father ran the Olympic, because it was much bigger and heavier. We were trapping in the high Selkirk Mountains, so it was common to get 40-60 centimetres of snow in a week. He would break trail and I would follow. When the snow became too deep and the machines bogged down, out came the snowshoes and I would start breaking trail one step at a time. In that deep, fluffy snow it was difficult, so I would only go about 300 metres and return to the snowmobile. I would get it unstuck, fire it up and away I went. Straddling my freshly broken snowshoe trail, I would get the machine up to full speed until that ole Bombardier hit the virgin snow, go 20 metres and come to a stop, stuck again. Out came the snowshoes and the process started all over again.

Many a Saturdays were spent breaking trail. We would return the following day to set traps. Then a few days later return to check the traps. This kind of fun went on from December to the end of February, when the high-country trapping season ended.

In the summer there was no trapping, of course, but it was still on our minds, and one of the highlights was making call scent for marten. There were two goals. First, it should not freeze. And second, it should be a stinking rotten scent, and the hot summer weather was perfect for this.

Here's how we did it:

During the summer, our recipe would cook and percolate on the roof. It was one of those odours that had to be acquired in order to appreciate the effort that went into making this eau du toilet scent.

All trappers understood the value and creativity of such a fine call scent and its importance in trapping marten. My mother, on the other hand, did not have the same appreciation for our efforts. She had a few choice words for us during those hot spells when she was hosting summer garden parties and the marten eau du toilet scent would waft its way down from the roof top and into the party.

• Shame on provincial governments! Shame on Air Canada! Canada has a free trade agreement with the USA, Mexico, Korea and others, but we don’t have free trade and free flow of goods within our own country! And can you imagine? Our national airline has an embargo on a wildlife species that the Inuit people of the Canadian Arctic legally harvest for sustenance!

• Sorry Mum! The first critters my father trapped, back in the 1920s, were skunks, when their fur was highly prized. He always joked that his wedding day, November 10, was also the first day of the skunk-trapping season. He told that joke for 72 years until he passed away on his 97th birthday. My mother did not quite see the humour. She says the joke wore off after the first five years.

• Squirrel surprise. When I was about 10, a chum and I ventured into the realm of squirrel cuisine. After hours setting up a spot in the woods, including a makeshift rotisserie, finding dry wood in three feet of snow with wet matches, smudge smoke in our eyes, wet clothes and cold feet, we were ready. We skinned and eviscerated that little critter, then stuffed it with hazelnuts and roasted it over an open fire. Surely this would be a mouth-watering meal, the best-tasting squirrel ever! Well, let's just say that it sounded better than it turned out. It was several more years before I ventured back into the fine cuisine of squirrel cooking.

SEE ALSO: Top 5 tasty furbearers: Muskrat stew and more

• Name-dropping. Among the many products my company makes are coyote fur collars for parkas, and one of our clients has an impeccable pedigree: Amundsen Sports of Norway. The name rings a bell, right? CEO Jorgen Amundsen is carrying on a family tradition of adventurers started by his great uncle, Roald Amundsen, the first man to set foot on the South Pole in 1911!

Fur-trimmed and down-filled parkas are everywhere in our cities these days, but is the coyote, fox or other fur trim…

Read More

Fur-trimmed and down-filled parkas are everywhere in our cities these days, but is the coyote, fox or other fur trim on the hoods just decorative, as activists claim, or does it really help keep us warm?

We're not all Inuit hunters, Iditarod dog mushers, or polar explorers, but we've all seen them, if only in pictures: men and women braving the elements in voluminous parkas, topped off by huge hoods with giant fur ruffs. Yet their faces are so exposed, and most of the fur trim doesn't even contact the skin, so can they really be that warm? Or are they just for show? Have faith: fashion statements are the last thing on anyone's mind when the mercury plummets and the wind picks up. Developed over millennia by the indigenous peoples of the Arctic, these ruffs work.

For most southerners, a parka hood is just about protecting the head from a bit of wind and rain. But people who work at –30°C, often for long periods, need much more. That doesn't mean bundling up like Himalayan mountaineers though, because beyond keeping warm, they also need to function effectively. Whether it's trapping, fishing, or driving a snowmobile, they want clear vision both in front and to the sides. Giant fur ruffs fit the bill perfectly.

Here are the key design features, and why they work so well:

There are two ways your body loses heat in cold weather: conduction and convection. Conduction is not a major concern for southerners, unless we get soaked to the skin, and then our body will cool down really fast, especially if there's a wind to add convection. And so we blithely pull our hoods close around our faces, and there may even be a draw string for just this purpose.

Now try ice fishing in Nunavut – or almost anywhere in Canada, for that matter – in January, and see what happens! Your hood's fur trim is tight up against your cheeks, right next to your mouth. Each time you exhale, the moisture in your breath forms ice on the fur. And since ice is a far better conductor of heat than air, your fur trim, far from keeping you warm, becomes a very efficient conductor of heat away from your face. Next thing you know, you've got frostbite.

Real polar ruffs greatly reduce this ice formation. The fur trim is still tight up against the face, but contact is made behind the cheekbones. Hence the exposed face we talked about.

SEE ALSO: Amazing facts about fur: Dressing for the Arctic

You also want your hood's fur ruff to be large. Your traditional caribou or seal skin parka is already bulky, so top it off with the lion-meets-angry-frilled-necked-lizard look! The most spectacular of all ruffs, a “sunburst" ruff, can measure three times the diameter of the wearer’s head!

Wind removes heat from your face by convection, and the faster it blows, the more heat it removes. But when the wind hits a solid object, a boundary layer is created in front of the object, inside which the wind slows down. The larger the object, the thicker and more insulating the boundary layer. Ergo, the greater the diameter of your fur ruff, the warmer you'll be.

This has long been intuitive to Inuit designers, and in fact to all of us. It's the reason why, when we face into a gale with a wall at our backs, the wind speed is much less than if we're standing in the open. The wall has created a boundary layer.

In 2004, a research team from the universities of Michigan, Washington and Manitoba quantified this boundary layer effect using a heated model of a human head, thermocouples, a wind tunnel, and a variety of hoods. As expected, the most effective hood by far in slowing heat loss had a sunburst ruff. It was particularly superior to other hoods when the wind was at a high yaw angle to the model's face, i.e., blowing from the side.

(For an excellent graphic showing how a fur ruff creates a boundary layer, see "Why fur-lined hoods are so warm," Chicago Tribune.)

The Inuit have also long understood that fur trim works best when the hairs are of varying lengths. This is naturally the case when traditional furs such as arctic fox, wolf, or wolverine are used, since they have long guard hairs and short underfur, and different parts of the pelt are different lengths. Coyote and fox also have these qualities and are more commonly available on modern parkas. The effect can be enhanced further by using two types of fur within one ruff.

The same 2004 research team sought to quantify this also, comparing the sunburst ruff with a "military hood" with short-haired fur of uniform length. Once again the sunburst ruff came out top, with the researchers concluding that a variety of hair lengths disrupts the wind flow more and thereby helps build an effective boundary layer.

One comparison not made by the researchers was between real fur trim and fake fur, but since fake fur hairs are uniform in length, the conclusion is unavoidable that fake fur trim can't compete with the real deal.

That aside, their conclusion was unequivocal: "The present experiments clearly demonstrate the superiority of the sunburst fur ruff configuration for all wind velocities and yaw angles tested. ... The sunburst fur ruff design is truly a remarkable 'time-tested' design."

The good news for everyone living south of the Arctic Circle is that we can all benefit from this "time-tested" design – perhaps just scaling it down a bit. Caribou or seal skin parkas are overkill for most of us, not to mention the stares they'd attract. But we can easily fit ourselves out with a down-filled hood with real fur trim that's plenty big enough.

The most popular fur for ruffs these days is coyote, which not only keeps us warm, but also dovetails with the need to manage a growing coyote population across North America. Fox can also be effective.

SEE ALSO: Abundant furbearers: An environmental success story

Truth About Fur's Alan Herscovici lives in Montreal, currently blanketed in snow, where temperatures in January average about -10°C, but have risen no higher than -20°C for much of this winter. With wind chill, it can feel like -30°C.

"Call us 'southerners' if you want, but there are days I feel like Nanook of the North," says Alan. "The coyote ruff on my parka has proven its worth this winter!"

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.

Animal-rights activists argue that we are not morally justified to kill animals for any purpose, and certainly not for products…

Read More

Animal-rights activists argue that we are not morally justified to kill animals for any purpose, and certainly not for products they consider to be non-essential, such as fur. But this view of morality may say more about the activists' understanding of society, of nature and of their own unique place within the big scheme of things than it does about people who produce or wear fur.

This thought came to me just before Christmas during a moving performance of Handel’s Messiah, by Montreal’s Metropolitan Orchestra and Choir with star conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Handel’s magnificent oratorio was premiered in Dublin, in 1742, under the direction of the composer; the beautiful libretto by Charles Jennens (1700-1773) is drawn from Old and New Testament texts.

– Isaiah 53:6 (from libretto of Handel’s Messiah)

The music is transcendental, but my thoughts returned to more earthly matters as the choir sang the verse: "... we have turned every one to his own way." Nine words that neatly sum up the guiding philosophy of modern Western society.

Don’t get me wrong: I am not romanticizing the time when the individual was required – often ruthlessly – to conform to the demands of family, clan, nation or religion. But the fact is that we, in our privileged Western societies, have ventured into uncharted waters: for the first time in human history, individual freedom and personal fulfilment are widely considered to be the most important goals, the ultimate "good".

We no longer accept that our marriage partners be chosen by our families, or that what we eat and how we behave be dictated by tradition or a parish priest. Today, each of us claims the right to make our own decisions. The individual is king.

What does this have to do with the radical shift in thinking proposed by animal-rights philosophers? Maybe a lot. Because, above all, believers in animal rights assert that the rights of each animal must be recognised as inviolable. It is the individual animal, not the population or species that is important, according to this view. And this has far-reaching implications. Let’s see how.

Most of us believe that humans have a right to use animals for food and other purposes, so long as animal populations are not diminished and species are not endangered. This is known as “sustainable use”. In other words, we eat chickens, but we don’t eat them all. Individual chickens are killed and eaten by individual humans – who will, in turn, one day themselves be eaten by worms, bacteria and other organisms – but both chickens and humans continue. In fact, with North Americans annually consuming some three billion chickens, and billions more eggs, one could argue that both chickens and humans are now very dependent on each other for survival.

A concern for animal welfare complements and deepens our sustainable-use values by acknowledging the individuals involved in this species-level symbiosis. The fact that individual animals die to provide for our needs implies, we believe, a responsibility to protect these animals from unnecessary suffering. In this sense, “animal welfare” seeks to balance the interests of groups and individuals.

The animal-rights philosophy, however, makes a quantum leap: the interests of individual animals are suddenly all that matter. According to animal-rights theorists, the individual chicken’s will-to-life is morally non-negotiable and irrevocable, no matter how useful their proteins may be for the health and well-being of humans – or, for that matter, for the survival of chickendom.

In other words, the animal-rights doctrine perfectly reflects our celebration of the individual in modern Western societies. And perhaps this explains, at least in part, why the animal-rights philosophy has considerable appeal in Western societies, especially among younger people.

Of course, our glorification of the individual is far from universal. Even today, most people live in societies where the individual has less autonomy, where their dependence on the group is more explicit. The moral force or “truth” of animal-rights arguments probably seem less evident in such societies.

And isn’t the dependence of the individual on the group a fundamental reality in all human societies? We live in cities, speak languages, use technologies, and have our spirits lifted by music that were all created by others, often people who are no longer with us.

A more profound challenge to the “truth” of the animal-rights philosophy comes from the fact that nature doesn’t show much consideration for individuals. In nature, individuals are short-lived and expendable; it is populations and species that continue.

This ecological truth does not diminish the importance of respecting human rights, but it reminds us that such rights are not rooted in nature or universal truth; they are created by human societies.

What is rooted in nature, however, is the dependence of all animals on other species – especially for food. Like it or not, only the living cells of other organisms can provide us with sustenance. No philosopher or activist can change this fundamental fact of our existence.

Nature is not moral or immoral, it just is. But humans do develop codes of morality, precisely because we live in groups and need each other. Without moral codes we would indeed be lost sheep. But if the animal-rights insistence on each animal’s irrevocable right-to-life is not defensible, what moral code regulates our use of animals?

When it comes to our relationship with animals, our moral code includes four main precepts. Two have already been mentioned: we should use only part of the surpluses that nature provides (“sustainability”), and we should protect the animals we use from unnecessary suffering (“animal welfare”). The other two moral precepts governing our relationship with animals are that we should not use animals for frivolous purposes (“important use”), and we should use as much of the animal as possible (“no waste”).

SEE ALSO: Why fur is the ethical clothing choice.

As I have explained in a previous article, the modern fur trade does respect all four of these important moral precepts. The use of fur, when it is responsibly and sustainably produced as it is today, is indeed morally justifiable, because it balances the needs of species and individuals in a way that is consistent with the way our world really works.

It is animal activists who are lost, who “have turned every one to his own way”, because their fundamentalist philosophy considers only the individual. In fact, as the great humanitarian and animal lover Albert Schweitzer once wrote: insisting that we harm no other life is not a solution to the moral problem that living beings kill and eat each other to survive – it is pretending that there is no problem.

It’s our first news roundup of 2018 so let’s review the fur headlines from December, including stories about sheep fur,…

Read More

It's our first news roundup of 2018 so let's review the fur headlines from December, including stories about sheep fur, farmers speaking up, and activists up to no good.

Let's start with fashion. December saw the showing of the Pre-Fall 2018 collections, which were jam-packed with fur, and proof that Gucci and Michael Kors' announcements are not a trend that is industry-wide. China has a huge appetite for the luxury material and we are seeing pro-fur stories in the fashion media and in opinion pieces. Whether you are looking for a fur coat, a trapper hat, or fur slides, there's something for everyone.

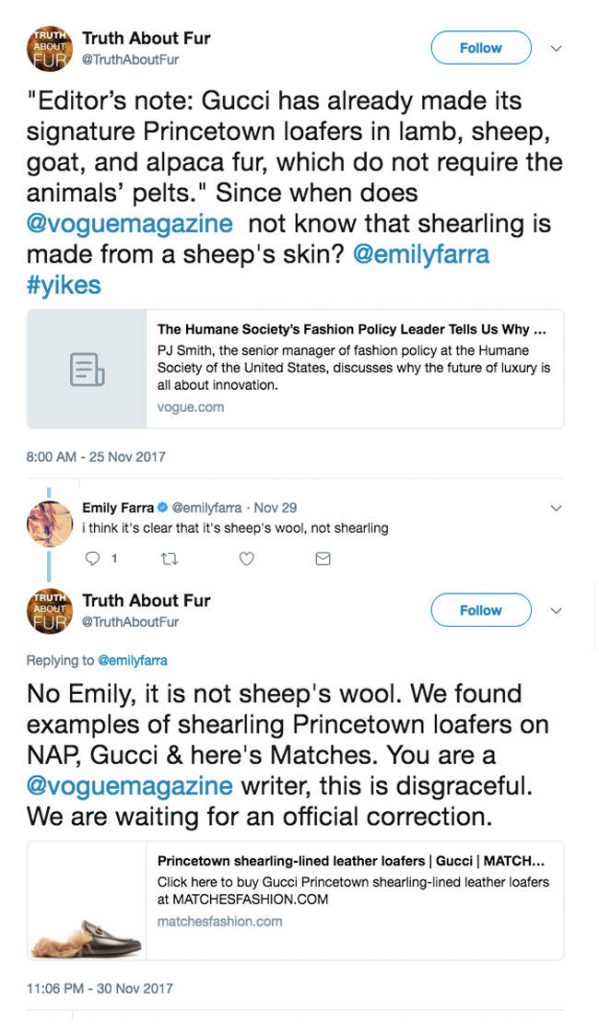

But the fashion media aren't all fur-savvy. A Vogue writer, Emily Farra, thought that sheepskin did not require the animals' pelts, so we decided to write up a piece about sheep fur. Also known as sheepskin or shearling, sheep fur is not wool, and uses the animals' skin and hair. Pamela Anderson is one of many people who didn't realise that sheepskin actually used sheep's skin, and now she is busy campaigning to get the Kardashians to give up fur. We are sure they will be willing to do it, for an hour or so.

The confusion about sheepskin and sheep fur raises questions about how far removed people are from animal husbandry and how farming works. An article entitled "The gulf between farmers and the people they feed is getting dangerously wide" is an excellent piece exploring this very concept – which has wide repercussions given that we all depend on farming for survival. This young British farmer has been very vocal about the fact that farmers "will always be here.(pictured)" And right she is, farming is such an important industry and animal rights activists have very little understanding of how it works. Speaking of how farming works, we loved this article about how mink farmers are using manure as biofuel.

Farmers and trappers don't often work side by side, but here's an example of how farmers are trying to preserve a trapping programme, in order to protect their livestock. It's one of many positive trapping stories from last month, including this feature on a passionate trapper, this article about how it is great to be in the woods, and this piece that breaks down the misconceptions of trapping. On the news front, we were happy to hear that wild fur buyers in Nebraska have been busy, people are waking up to the opportunities of nutria, and the Thompson fur table is doing a bustling trade.

There's less good news from the protest front lines. This Mother Jones piece exposes how activists are willing to take more risks to push their agendas. From death threats to homesteaders, startling ponies carrying children, declaring war on macaroni and cheese, and threatening hunters, it is clear they will stop at nothing to fight their often ridiculous and hypocritical causes. We highlighted some of this hypocrisy in a recent blog post, where we explained that being anti-fur and anti-pipeline (pictured) is actually quite contradictory. But despite their threats, their inability to distinguish between sheep fur and wool, or their ridiculous hunger strikes, people are beginning to question whether animal rights are unconstitutional, and if veganism is culturally insensitive.

Let's end December's roundup with a few stories that caught our attention last month:

The Russians are doing it better - at least when it comes to fur education for kids.

Sea Shepherd have given up fighting the Japanese whalers.

If you are disposing of a Christmas tree this week, pat yourself on the back. Like fur, it is way better to shop real than fake.

And grocery shopping can be more dangerous than you think. (pictured)

It’s Christmas time so, for a change of pace, let’s wander off the topic of fur, and on to Christmas…

Read More

It’s Christmas time so, for a change of pace, let’s wander off the topic of fur, and on to Christmas trees. So which are best for the environment, real trees or fake trees? You may find some of the arguments familiar!

We are flies on the wall at the dairy farm of Fred and Mary in upstate New York, where son Nick is visiting for the festive season along with his wife, Nancy. Since Nick grew up on the farm, he knows all about milking and mucking out, but Nancy is a city girl from Rochester, where she works as a personal lifestyle coach.

“A what?” Fred and Mary had asked the first time they’d met Nancy. In the years since, good-natured goading had become a part of Christmas family tradition, but it was always a two-way street because Nancy’s knowledge of nature was as pitiful as Fred and Mary’s knowledge of city life.

“Why must your cows be pregnant when you’re just using them for milk?” she’d asked one year. “And how is it even possible? They’re all female!”

This year, with a couple of days to go to Christmas, they all climbed in Fred’s truck to see a friend who had a beautiful tree picked out for them. In the back seat, Nancy lovingly caressed her early gift from Nick, a big, bouncy, faux fur fox hat. Behind the wheel, Fred proudly wore his Daniel Boone hat, made by a local artisan from a roadkill raccoon Nick had run over.

“Faux? That means fake, right? Plastic?” Fred asked Nancy, knowing perfectly well what it meant. “Well at least it hasn’t got rabies!” Nancy shot back, pointing at Fred’s head. “For the umpteenth time, my hat does not have rabies!” Fred began, before Mary intervened. “You both look lovely!” she pleaded.

Shortly after, they were headed home with a spectacular nine-foot spruce hanging off the flatbed. Fred and Mary were beaming, while Nick looked anxiously at his wife. She was bursting to say something!

“Poor tree,” she muttered, and Fred eased off the gas. “Come again?” he said. “Uh oh,” said Mary and Nick.

“Why can’t you just get an artificial tree?” said Nancy. “You know, save the planet?”

Fred stroked the tail of his raccoon hat meaningfully.

“If everyone bought a real tree,” continued Nancy, “soon there wouldn’t be any left – like what’s happening in the Amazon.”

“Seriously?” responded Fred. “That’s like saying we’ll run out of carrots if too many people eat them. That was a farm we just visited, and each year my friend plants saplings to replace the ones he’s sold. His family’s been doing it for forty years, and they’ve got more trees now than when they started! Some trees do come from forests, but even those are managed so they don’t run out.”

“But why take the chance?” said Nancy. “If we need more artificial trees, we just make more. They’ll never run out.”

“Never? It’ll take a long time,” conceded Fred. “But most fake trees are made of PVC, and one of the ingredients for making PVC is oil. That’s a non-renewable resource. So if anything won’t run out, it’s real trees.”

Nancy rallied fast. “But real trees are so wasteful. After just a few weeks you’ll throw yours in the garbage, while mine will last for years.”

“Actually, we use our trees for all sorts of things,” explained Fred. “Mary puts the branches on the flower beds to insulate the plants against frost. I chop up the trunks for firewood. And there’s a truck that collects them too, and puts them in the chipper to make mulch for the parks. And even if they just get tossed on the garden, they just become worm food. Like you say, PVC trees will last for years, but they’ll still end up in landfills, polluting groundwater for the next thousand years.”

“Heh, artificial trees can be recycled too!” said Nancy.

“That’s true. PVC is easy to recycle once or twice,” conceded Fred, “but it weakens with time and most still ends up in landfills, and it doesn’t biodegrade – it doesn’t become worm food. A lot is also mixed in with household waste and is incinerated to produce electricity, but that releases harmful dioxins into the atmosphere.”

SEE ALSO: Santa wears fur "from his head head to his foot"

“In fact,” he continued, “since we’re on the subject of pollution, greenhouse gases are emitted during the making of fake trees, but buying a Christmas tree from a farm is a carbon-neutral purchase.”

“A what?” spluttered Nancy.

Nick took pity on her. “Trees sequester carbon dioxide, right? They absorb it and store it. Now carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas, and if we cut down all the trees, it would be released back into the atmosphere, worsening global warming. But each time a farm cuts down one tree, it replaces it with another, so on balance, no carbon dioxide is released into the air. So it’s a carbon-neutral purchase.”

Nancy glared at him. “How about a divorce? Is that carbon-neutral?” Nick stifled the urge to laugh. “Sorry, dear. I’ll be quiet.”

“So how about all those people driving out to tree farms in their gas-guzzling trucks to buy their trees?” asked Nancy. “Or are they all driving Teslas? I don’t think so!”

“Nancy dear, they don’t drive Teslas when they go to the mall to buy a fake tree either,” interjected Mary in her best peacemaker tone. “More importantly, real trees are farmed close to consumers, while your fake tree probably came all the way from China. So the greenhouse gases involved in shipping fake trees are much higher. Right, Fred?”

Fred grunted, sensing he’d said enough.

“Well, how about the cost to you personally?” Nancy asked Mary, mimicking her sweet tone. “Each year, you spend $100 on a tree that lasts a few weeks. I bought mine for a little more, but it’ll last for 20 years.”

“Bingo!” said Fred, unable to keep his mouth shut. “And that’s the only reason for buying a fake tree. It’s cheap. But in the long term, there’s a price we all have to pay. Real trees are sustainably produced and don’t harm the environment. But fake trees are unsustainable and polluting.”

“Stop the car, Dad! Dead raccoon!” shouted Nick suddenly. “Are you sure you don’t want a hat like Dad’s, Nancy?”

In the fur trade we see all kinds of hypocrisy from our critics, and one that we see regularly is…

Read More

In the fur trade we see all kinds of hypocrisy from our critics, and one that we see regularly is people who protest pipelines and also protest fur.

If you live in a country that has a real winter, you’ll need winter clothing for survival. There are really only two types of material suitable for winter clothing: animal based materials (such as fur, leather, shearling, wool, and cashmere) and synthetics. Anyone who is against fur is presumably against the use of other animal materials (if not, you are really not thinking very clearly, but that’s a story for another day), but anyone who is against pipelines should presumably be against synthetics, because most synthetics are made from petroleum by-products.

So why do we constantly hear the animal activists touting the benefits of fake fur as an alternative to the real thing? That’s a question we just can’t answer. We frequently run across anti-fur folk who promote synthetic alternatives, yet are against pipelines. Maybe someone needs to tell them that those pipelines are needed to produce the plastic clothing they want us all to wear. Most people protest pipelines because they want to protect pristine nature. So wouldn't it make sense that these people would also be against wearing clothing made from petroleum by-products, which, we are now learning, pollutes our air and water with micro-particles of plastic when washed, and then sits in a landfill for a thousand years when discarded?

SEE ALSO: Hypocrite profile: Stella McCartney

We are in a fragile situation right now on the planet – rising temperatures, oceans accumulating plastic, and a dependence on non-renewable energy. A life without fossil fuels in the near future is going to be close to impossible, but we should be looking at reducing our consumption of them. Petroleum is not easy to extract, it’s not good for the environment, and it is not renewable. Solar power, wind farms, and electric cars are all helping us move away from the use of petroleum, but this will take time. Meanwhile, though it is hard to give up on gas or certain plastics, we can easily reduce our consumption of some petroleum-based products: notably, single-use plastics (water bottles – I’m talking to you) and synthetic clothing.

Yet we hardly hear about reduction of synthetic fibres as a viable way to reduce our dependence on petroleum products and the pollution these materials cause. And this is surprising – given that there are many animal and plant-based alternatives to synthetic fabrics that are as viable and useful as synthetics. No fabric is perfect, and everything requires energy to produce, but the materials that are sustainable, long-lasting, and biodegradable should always be the first choice. Imagine how dramatically our consumption of plastic clothing would decrease if we all pledged to wear clothing items for five years instead of one. Not only would we buy less, but we would probably buy better quality (and therefore less synthetics) in order to ensure that the garments lasted longer.

SEE ALSO: Hypocrite profile: Ricky Gervais

It’s easier to choose a leather shoe over a synthetic one, than it is to find an airline that will fly you to your holiday destination in an electric plane. And while the effect of plastic clothing may not be the most hurtful to the environment (compared with cars and industrial pollution), the damage is nonetheless scary. Microplastic particles are now being found in our food, water, and air – and the culprit is often synthetic clothing. Next time you eat an oyster burger washed down with a pint of your favourite local ale, keep in mind that you are getting a side dish of plastic particles, free of charge.

It doesn't make sense to protest pipelines and be against the use of animal products in clothing. If you are concerned about the planet and our consumption, then by all means let’s try and reduce our dependence on fossil fuels and let’s encourage more renewable forms of energy. But if that’s your stance, then your wardrobe had better reflect that as well. If you are aiming to live an environmentally conscious life, then your wardrobe should include clothing made from plant-based materials and animal products, produced sustainably and ethically, made to last, and when they find themselves ready for the landfill, your wardrobe should biodegrade and return into the cycle of nature.

SEE ALSO: Hypocrite profile: Pink

But if you choose to protest pipelines while wearing synthetic clothing made from petroleum co-products, you may find yourself in a conflicting position (read: you are a hypocrite.) Fur is a natural, renewable resource and fur clothing is warm, long lasting, and biodegradable. A synthetic fleece jacket made from petroleum co-products releases plastic particles into the water and the air every time you wash and dry it, and will end up in a landfill for thousands of years, never able to fully biodegrade. How many 30-year-old fleece jackets do you find being handed down from one generation to the next? Not many. But you might find me on my way to protest pipelines wearing the 40-year-old muskrat coat my grandmother gave me a few years ago.

Something that keeps writers like me employed is that no matter how good we are at spreading the truth, when…

Read More

Something that keeps writers like me employed is that no matter how good we are at spreading the truth, when the next generation comes along there are things we have to teach all over again. Such is the case with the clothing material popularly known as sheepskin, lambskin or shearling. And the lesson that needs constant repetition is that it is not wool, it is sheep fur, and animals die to produce it.

In defence of those who find this confusing, it's true that the word "fur" is popularly used to mean the skin and hair (or pelt) of particular types of animal, like mink or fox. But in fact, every hairy animal can provide fur, including sheep, which do so in vast amounts. We just don't call it fur. Sheep fur is variously called sheepskin or lambskin, while the fur of a sheep which has been recently sheared is called shearling.

And just for total clarity, when we use sheep hair without the skin attached, it's called wool, and no animals are killed to produce it.

In the context of the great fur debate, these are important distinctions because many people are wearing fur without even knowing it, including some people who should know better.

The most memorable case of someone not being able to put two and two together was Pamela Anderson. During her Baywatch days, she almost single-handedly turned Ugg sheepskin boots into a major fashion trend. She then took up the cudgels for PETA, campaigning against the practice of mulesing sheep while still wearing her trademark Uggs.

For some unknown reason, PETA decided not to tell Pam what Uggs were made of, but finally the penny dropped. "I'm getting rid of my Uggs," she wrote on her website in 2007. "I feel so guilty for that craze being started around my Baywatch days. I used to wear them with my red swim suit to keep warm never realizing that they were SKIN! I thought they were shaved kindly. People like to tell me all the time that I started that trend - yikes!"

But the point here is not just to have a laugh at Pam's expense. She is a high-profile example of a pervasive ignorance found not only among the general public but even in the world of fashion.

This November, Vogue (UK) interviewed Gucci's new handler, the Humane Society of the US, about the brand's decision to go "fur-free". As we shall see, there's cause for scepticism when brands like Gucci, which use a lot of shearling, make this claim. Will they be dropping all furs, including sheep fur, or just the mink and fox?

Never fear, reported Vogue's interviewer, Emily Farra; Gucci had all the bases covered. "Gucci has already made its signature Princetown loafers in lamb, sheep, goat, and alpaca fur, which do not require the animals’ pelts," she wrote. Really? What is "alpaca fur" if it's not a pelt? More significantly, Gucci is quite open about its sheep-based Princetown loafers being lined with shearling, and, yes, that means the whole pelt – skin and hair.

We called out Ms. Farra on Twitter, but she refused to see the light ...

Ignorance about sheep fur persists in part because neither designer brands that use it, nor the animal rights groups that handle them, are forthcoming with the truth. It's a trade-off. In return for brands declaring themselves "fur-free", their animal rights handlers turn a blind eye to the fact that sheep pelts are fur.

SEE ALSO: Why is Giorgio Armani really quitting fur?

A shameless example of this duplicity is Ralph Lauren. Since 2006, it has been "100% fur-free" and compliant with "PETA guidelines". In reality, it uses a huge amount of sheep fur, often disguising it as other types of fur, necessitating the following footnote to the show notes of a recent collection: "Ralph Lauren has a long-standing commitment to not use fur products in our apparel and accessories. All fur-like pieces featured in the collection are constructed of shearling."

Talk about double-speak! Both Ralph Lauren and PETA are surely aware that shearling is fur, and yet they insult our intelligence by pretending otherwise. And they get away with it because, as Pam Anderson and others have proved, intelligence is in short supply where sheep fur is concerned.

For anyone who still doesn't get it, here's the short version: Sheepskin, lambskin and shearling are all fur. And yes, animals die to produce them.