Fur Bans: Society Has Much More to Lose than Fashion

by Alan Herscovici, Senior Researcher, Truth About FurWhen animal activists pressure designers to stop using fur in their collections, or politicians to ban the sale of fur…

Read More

When animal activists pressure designers to stop using fur in their collections, or politicians to ban the sale of fur products in their cities, we rarely consider what society would lose if we turn our backs on fur.

Activists claim that fur is a frivolous luxury; that no one needs to wear fur anymore. But fur is a natural, sustainable and responsible clothing material. And we will lose a lot more if activists are successful in vilifying fur.

Let’s take a look at what we lose as a society if we allow animal activists to dictate the discussion about fur:

1. Fur Craftsmanship – a Remarkable Heritage

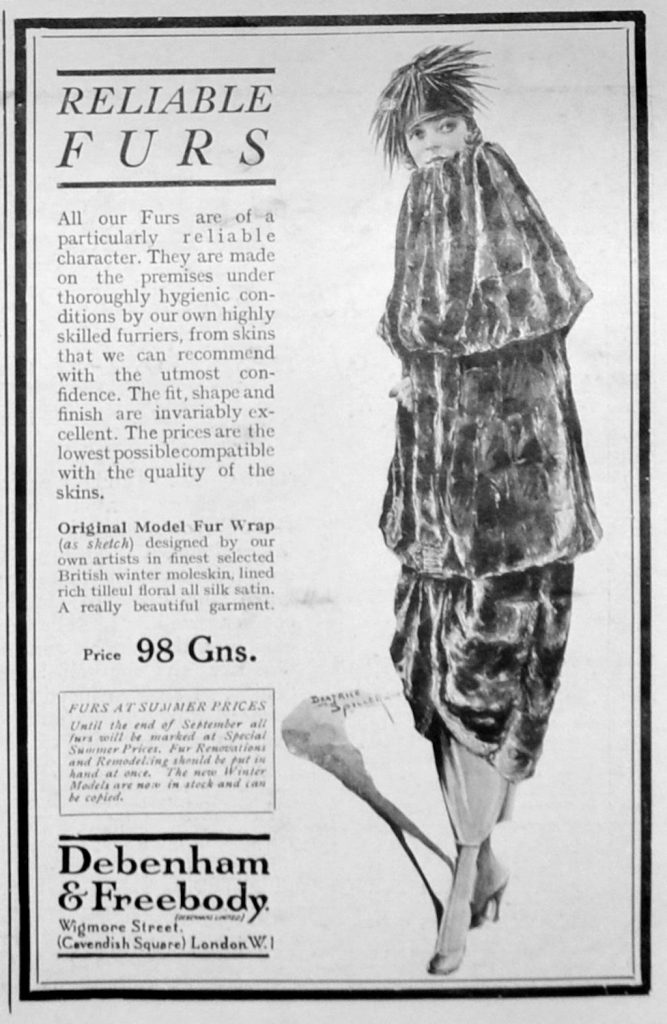

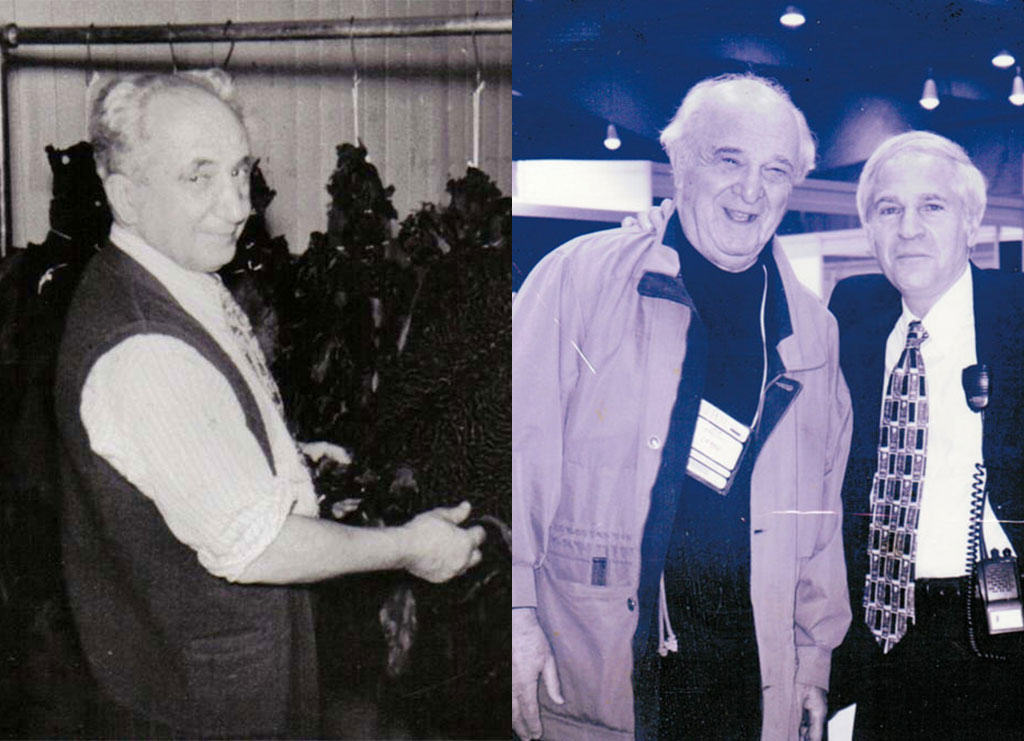

This issue is close to my heart because my paternal grandfather was trained as a furrier by his father, in Paris, before coming to Montreal as a young man, in 1913. My own father also worked his whole life in the trade. So I am saddened that there is so little recognition or respect for this remarkable heritage industry. In this age of impersonal mass-production, fur is one of the few clothing materials that are still hand-crafted, by skilled artisans. Specialized knowledge and skills are needed to select, cut, sew, and assemble fur pelts to produce a beautiful garment or accessory. These skills have been maintained and perfected through centuries, passed down from parents to their children.

When I bring someone into a fur atelier, even people with experience in the apparel industry cannot believe that anyone is still doing this sort of meticulous hand-work. Fur craftsmanship is a wonderful example of the sort of authenticity many hipsters and others are seeking today. Fur apparel and accessories represent the marriage of human creativity with the beauty of natural materials.

The fur artisan’s skills and knowledge are part of our cultural history and heritage; they should be valued and protected - like world heritage sites and endangered species - not vilified, especially at a time when such handicrafts have become so rare. Like the wanton destruction by the Taliban of giant Buddhas carved into the mountainside at Bamiyan, in Afghanistan, or the burning of ancient libraries in Timbuktu by Islamic insurgents, the misguided scapegoating of centuries-old fur skills shows a complete lack of understanding and respect for our cultural heritage and the diversity of human experience.

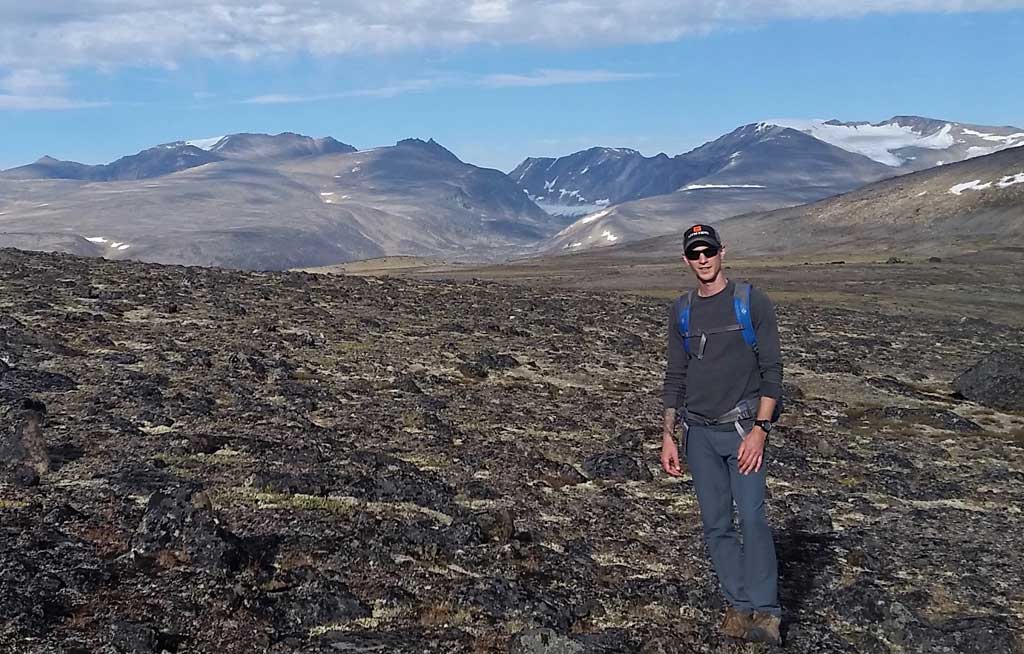

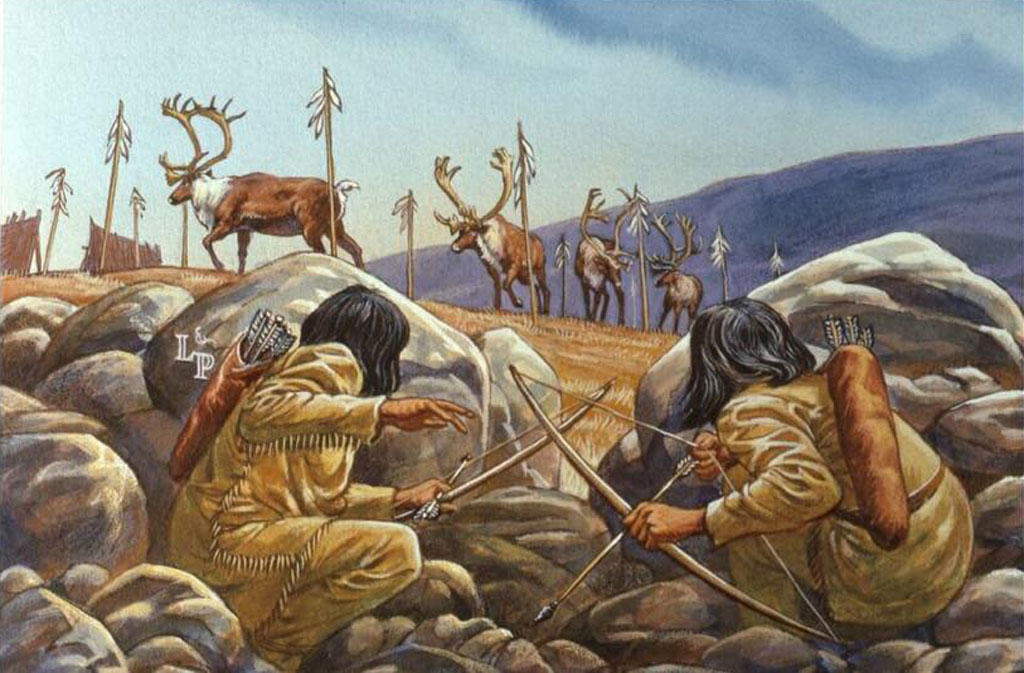

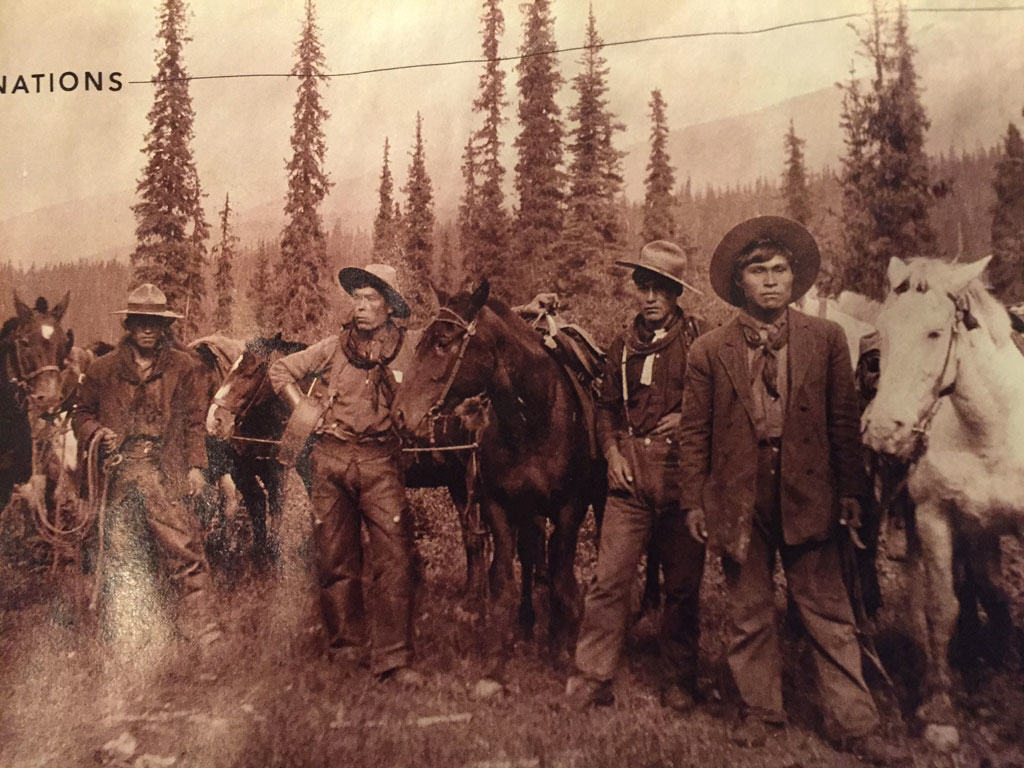

2. Fur Trappers – True Stewards of the Land

If ever you’re in a plane that crashes into the northern wilderness, you’d better hope there’s a fur trapper aboard, someone with the skills and experience to provide food and keep the rest of you alive. We all care about nature, but most of us now live in cities and depend completely on complex distribution systems for our needs. Trappers are among the few who still go into the bush, alone, with only their knowledge of the land and animals to maintain themselves. Trappers are, in fact, our eyes and ears on the land; they are the ones who can sound the alarm when nature is threatened by industrial pollution or poorly planned development. It is trappers who inform logging companies about the location of eagle nests and other important habitat, so they can be protected. It is trappers who call in government wildlife biologists when they spot problems. At a time when we claim to care about protecting nature, we should respect the skills and knowledge of those who still live close to the land.

SEE ALSO: Trapping and sustainability.

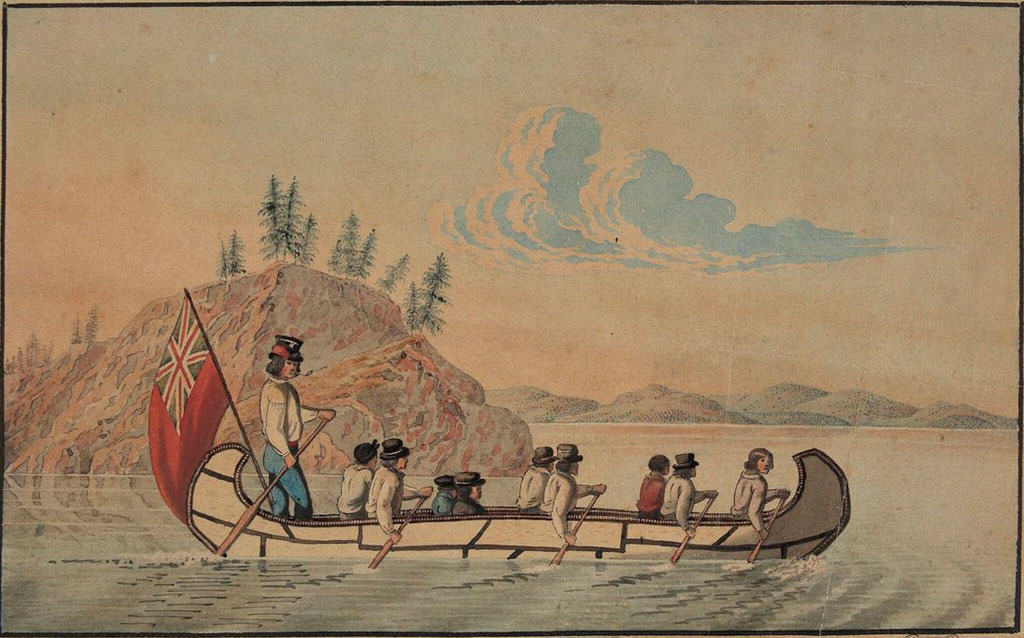

First Nations and other trappers do not need lessons about respecting nature from urban activists! But activists have easy access to city-based journalists, and have mastered all the tricks to attract media attention. As PETA founder Ingrid Newkirk says, “We’re media sluts; we didn’t invent the game, we just learned how to play it!” With hundreds of millions of dollars in contributions from well-meaning urban supporters, this flourishing new protest industry has painted trappers as exploiters or enemies of nature, a complete falsehood. In fact, the well-regulated modern fur trade is an excellent example of sustainable-use principles promoted by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

In simple terms, trappers take part of the surplus that nature produces every year. Only abundant furbearers are used, never endangered species. By taking part of the natural surplus, trappers help to smooth out population “boom and bust” cycles, maintaining more stable and healthy furbearer populations. Unfortunately, trappers live far from the media centres, and their voices - the voices of the true guardians of nature - are rarely heard.

SEE ALSO: Reasons we trap.

3. Fur Farmers – Supporting Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Communities

Thanks to more efficient practices, farmers now represent barely 2% of the North American population, compared with about 33% in 1900 - a demographic shift that poses challenges for the viability of rural communities and services. Fur farms provide needed employment, especially because mink and foxes can be raised on small parcels of land, and in regions where the soil is too poor or the weather too harsh for most other forms of agriculture.

Farm-raised mink and foxes are fed left-overs from other animal production, the parts of chickens, pigs, fish and other food animals that humans don’t eat. The manure, soiled straw bedding, and carcasses of the fur animals are composted to produce high-quality natural fertilizer to replenish the soil, completing the agricultural nutrient cycle.

The farm-raising of fur-bearing animals, which began in North America more than 120 years ago, also provides an efficient safety valve to reduce pressure on wild populations. And with careful selective breeding and excellent care, North American fur farmers have developed a remarkable range of natural colour ranges in mink and fox, reducing the need for the dyes needed with most textiles. Not least important from a social perspective, most fur-bearing animals are raised on family-run farms.

Natural, Renewable, Recyclable, Long-Lasting, Biodegradable

Fur craftspeople, trappers and farmers – together with fur buyers, processors, and a range of other specialized workers – maintain skills and knowledge that are part of our cultural heritage.

None of that would matter, of course, if animal species were being endangered or abused. But the modern fur trade is now conducted responsibly and sustainably. Trapping is strictly regulated by state and provincial wildlife departments, to ensure that only abundant furs are used, never endangered species.

North America is also the world leader in humane trapping research and development – work that provided the scientific basis for ISO standards, best practices, and the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards. Mink and fox farmers follow codes of practice to ensure excellent nutrition and care for their animals; this is the only way to provide the high-quality fur for which North America is known internationally.

SEE ALSO: Neal Jotham: A life dedicated to humane trapping.

Above all, fur is a natural, renewable, recyclable, long-lasting and ultimately biodegradable clothing material. After many decades of use, a fur garment or accessory can be thrown into your garden compost where it will return to the soil. By contrast, fake furs and other synthetic materials promoted by animal activists are generally made from petroleum, and are not biodegradable.

Simply put, most synthetics are another form of plastic bag. Troubling new research is revealing that these synthetics leach micro-particles of plastic every time they are washed - tiny plastic particles that are now being found in marine life and even in bottled water. Such synthetics may not be expensive to purchase, but they are very costly for nature and wildlife.

A sustainably produced, long-lasting and biodegradable natural clothing material. A rich heritage of increasingly rare craft skills. Support for rural and remote communities, and the responsible use and conservation of nature. The more closely we look, the more we understand how much we have to lose if we allow misinformed “animal rights” campaigns to turn designers, consumers and political leaders against North America’s founding industry.

***

To learn more about donating to Truth About Fur, click here.